A Japanese Zero Pulled Alongside Eight American Dive Bombers — Unaware That Would Be Nearly His End…

On August 7th, 1942, in the broiling, unforgiving sky over Guadalcanal—a place already destined to become one of the most brutal battlegrounds of the Pacific—a single encounter unfolded that would defy logic, violate expectation, and challenge everything both sides believed about survival in aerial combat. The morning sun had barely risen high enough to pierce the clouds when a Japanese A6M Zero fighter, sleek and lethal, sliced through the humid air toward a formation of American dive bombers. What began as a standard attack run would become one of the most astonishing feats of endurance in aviation history, though no man present could possibly comprehend its scale at that moment.

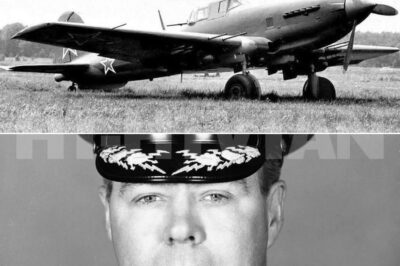

The Zero approached with calculated precision, targeting a group of American aircraft that were, on paper, hopelessly vulnerable when caught from behind. These were not fighters. They were SBD Dauntless dive bombers—heavy, armored machines primarily designed to plummet toward ships, release bombs, and yank upward just before impact. They were not built, nor intended, to outmaneuver an enemy fighter as light and agile as the Zero. Yet the Japanese pilot closing in on them did so under a single, fatal misunderstanding.

He believed they were not dive bombers at all.

He believed they were Wildcats—F4F fighter aircraft flown by the Americans.

This mistake would nearly kill him.

Among the American formation was the rear gunner Harold Jones, a young enlisted sailor serving aboard an SBD Dauntless from USS Enterprise, one of the American carriers supporting the Marine landings at Guadalcanal. His position, facing backward with twin .30-caliber machine guns at the ready, was often the difference between life and death. The Dauntless was slow, but it had teeth, and the men assigned to those rear guns were trained to fire with cold precision in moments measured by heartbeats.

When the Japanese Zero pulled in closer, gliding confidently into range, the American gunners opened fire—not one or two, but all eight of them.

Tracer rounds laced through the air with violent clarity. The Zero was suddenly hit from all directions, bombarded by incoming fire it had not expected, illuminated by streaks of light that carved through the sky. Among those rounds was a single bullet that would alter the fate of the Japanese pilot, whose name would later become known around the world: Saburō Sakai.

Harold Jones watched the spectacle unfold in real time. He saw pieces of the Zero’s skin tear away. He saw the canopy explode into glittering fragments. He saw the once-controlled fighter tip upward, wobble unnaturally, and drift out of alignment. Through the torn metal and shattered glass, he glimpsed what he believed was a lifeless pilot slumped forward, unmoving.

Jones and the others counted him as a kill.

They had no reason to doubt what they had seen. The Zero’s upward drift looked like the last reflex of a mortally wounded machine, the final uncontrolled lift before gravity reclaimed it. The formation completed its mission, returned to the USS Enterprise, and reported the fighter destroyed.

But Saburō Sakai was not dead.

Not yet.

The .30-caliber bullet that struck his aircraft had torn through the canopy and carved into his head, entering just above his right eye. It obliterated the vision in that eye, filled his cockpit with blood, and nearly killed him instantly. For a moment, suspended in a haze of pain so profound he could barely identify where sky ended and death began, Sakai considered ending everything in a single violent gesture. He contemplated diving his damaged Zero straight into an American ship—dying as a kamikaze even before the term existed in its wartime context.

But there were no ships nearby. Only jungle. Only ocean. Only sky.

And then something else pulled him back.

Responsibility.

He was a section leader. His squadron needed experienced pilots more desperately than ever. Japan needed experienced pilots even more. To die now—senselessly, impulsively—was to abandon that responsibility. And so he pushed aside the impulse to surrender to gravity and instead made a decision that would test the limits of endurance: he would fly home.

This meant flying 560 miles.

In a damaged aircraft.

While half-blind.

Bleeding heavily.

Barely conscious.

The Zero’s controls felt heavy, the world around him swimming in and out of fading awareness. The flight from Guadalcanal back to Rabaul should have taken hours under ideal conditions, but his wounded state transformed those hours into an ordeal no pilot should have survived. Every second demanded clarity he did not possess, judgment he struggled to maintain, and strength that drained steadily with every mile.

Yet somehow, impossibly, Saburō Sakai kept the aircraft aloft.

When he finally reached Rabaul nearly five hours later, the ground crew ran toward the landing Zero expecting to pull out a corpse. The plane itself looked like a ruin that had continued flying through sheer force of stubborn defiance. But Sakai refused to die. Even as his vision dimmed and his body threatened collapse, he insisted on giving his after-action report to his commanding officer before accepting medical treatment.

Only when his duty was done did he fall unconscious.

Doctors doubted he would live. The head wound was devastating. Infection was nearly inevitable. And even if he survived, no one believed he would ever fly again. The destruction of his right-eye vision seemed to guarantee the end of his combat career.

But Saburō Sakai survived. He recovered. He adapted. By 1944, in a reversal so improbable that it seemed to defy medical reality, he returned to combat—flying once again in a Zero, navigating with one good eye, still driven by the same unyielding focus he had carried since the beginning of his career.

To understand the magnitude of this resilience, one must examine where Sakai began.

He was born in 1916 in Saga Prefecture, Japan, into a family that traced its lineage back to samurai ancestors. But that noble lineage had long since collided with modern reality. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan’s warrior class had been forced into civilian life, and Sakai’s family lived as farmers—respected but not wealthy, rooted not in privilege but in labor.

When his father died, Sakai was only eleven. His prospects narrowed with brutal immediacy. By sixteen, with almost no tangible opportunities before him, he enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1933. He served as a gunner aboard the battleships Kirishima and Haruna before attempting—and failing twice—to enter naval flight school. Only on his third attempt did he finally pass.

What awaited him there was training so ruthless it bordered on ritual combat. Wrestling matches that could break bones. Swimming tests designed to push bodies past their limits. And an unspoken understanding: fail to meet the standards, and you would be sent back to regular duty in disgrace.

Sakai did more than survive. He excelled.

He graduated first in his class. Emperor Hirohito himself presented him with a silver watch—a gesture rarely bestowed on any trainee. By the time he flew over Guadalcanal in 1942, Sakai was already one of Japan’s most experienced pilots, having fought across China, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, and New Guinea. Official records credit him with 28 victories, though his autobiography lists more than 60.

Meanwhile, Harold Jones—the man who nearly killed him—was simply doing his duty as a rear gunner aboard a Dauntless launched from the USS Enterprise, tasked with protecting his aircraft during the opening phase of America’s first major offensive in the Pacific. The Japanese airfield on Guadalcanal had to be stopped before it became a launching point for bombers that could sever Allied supply lines.

Two men. Two machines. Two nations locked in a conflict that redefined violence.

And forty-one years later, in a world transformed beyond recognition, those same two men—Saburō Sakai and Harold Jones—met face to face. They shook hands. They exchanged gifts. They spoke not as enemies but as survivors bound by the same memories of the same sky.

But that moment of reconciliation, decades after the war, was built atop a foundation of events that unfolded with far darker complexity on that August day in 1942…

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

August 7th, 1942, over Guadal Canal. A Japanese Zero fighter attacks a formation of American dive bombers. The rear gunner fires back. A single bullet pierces the Zero’s canopy and strikes the pilot in the head. The Americans watch the Zero tip upward, seemingly out of control. The pilot appears dead, slumped in his seat. They count him as a kill and return to their carrier. But Saburro Sakai wasn’t dead. Blinded in one eye, bleeding, barely conscious, he flew 560 mi back to base. The flight took nearly 5 hours. 41 years later, Sakai met the gunner who shot him, Harold Jones, the man who nearly killed him. They shook hands, exchanged gifts, and became friends.

Saburro Sakai was born in 1916 in Saga Prefecture, Japan. His family descended from samurai, but lived as farmers after the major restoration, forced warriors into civilian life. When his father died and Sakai was 11, his prospects narrowed. At 16, with few options, he enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1933.

He served as a gunner on battleships Kiroshima and Haruna. In 1937, after three attempts, he passed the entrance exam for naval flight school. The training was the most rigorous in the world. Wrestling matches that could end in injury. Swimming tests designed to weed out the weak. Pilots who couldn’t meet standards were sent back to regular duty in disgrace.

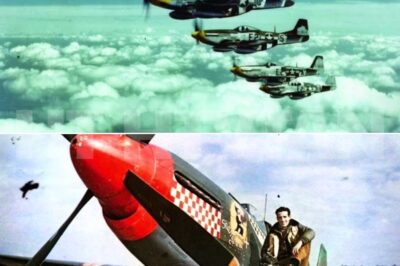

Sakai graduated first in his class. Emperor Hirohito personally presented him with a silver watch. By 1942, Sakai was a combat veteran. He’d flown in China, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, and New Guinea. He’d mastered the A6M0 fighter, light, agile, deadly in the hands of a skilled pilot. Official records credit him with 28 victories.

His autobiography claims over 60. Harold Jones was an American sailor serving as a rear gunner on SBD Dauntless dive bombers. The SBD was a sturdy aircraft, heavily armored, designed to attack enemy ships. The rear gunner sat facing backward with twin 30 caliber machine guns, protecting the aircraft from fighters attacking from behind.

Jones and his pilot were part of the air group aboard USS Enterprise, one of the American carriers supporting the marine landings at Guadal Canal in August 1942. The invasion of Guadal Canal was America’s first major offensive in the Pacific. The Japanese had built an airfield there. If they completed it, Japanese bombers would threaten Allied supply lines across the South Pacific.

The Marines had to take it. On August 7th, 1942, as Marines stormed the beaches, Japanese aircraft from Rabul, 560 mi away, launched counterattacks. Among the pilots was Saburo Sakai. That morning, Sakai and his squadron took off from Rabul. The flight to Guadal Canal took hours. When they arrived over the island, they engaged American fighters protecting the landing force.

Sakai shot down an FRF Wildcat flown by James Pug Southerntherland in an extended dog fight. Both pilots demonstrated exceptional skill. Eventually, Sakai scored hits beneath Southerntherland’s leftwing route. The Wildcat went down. Sutherland survived and would later become an ace himself. After that engagement, Sakai spotted what he thought was a formation of eight F4F Wildcat fighters.

He moved in to attack from behind. He was wrong. They weren’t wildats. They were Sbid Dauntless dive bombers, and dive bombers had rear gunners. Sakai realized his mistake only when he pulled close enough for the tail gunners to open fire. All eight rear gunners engaged him simultaneously. Traces filled the air.

Cannon rounds and machine gun bullets tore into his zero. Among those gunners was Harold Jones. Jones watched pieces of Sakai Zero fly off. The canopy shattered. The aircraft tipped nose up and appeared to stall. Through the damaged canopy, Jones caught a glimpse of what looked like a dead pilot slumped in the cockpit.

Zakai Zero climbed away, seemingly out of control. Jones and the other gunners believed they’d killed him. The formation returned to Enterprise and reported the Zero destroyed, but Saburakai wasn’t dead. A30 caliber bullet had pierced his canopy and struck him in the head just above his right eye. The impact destroyed his vision in that eye.

For a moment, Sakai considered dying like a kamicazi. Diving his damaged zero into an American ship below. But there were no ships close enough, only jungle and ocean. Then he thought of his responsibilities. He was a section leader. His squadron needed experienced pilots. Japan needed experienced pilots. Dying accomplished nothing, so he decided to fly home.

Sakai was 560 mi from Rabul. His Zero was damaged, but still flyable. He was bleeding, half blind, in terrible pain. The flight would take nearly 5 hours. He pointed the nose toward Rabul and began the longest flight of his life. Ground crew ran to his aircraft, expecting to pull a corpse from the cockpit. Instead, Sakai insisted on giving his afteraction report to his commanding officer before accepting medical treatment.

Only after delivering his report did he collapse. Doctors didn’t expect him to survive. The head wound was severe. Infection was almost certain. Even if he lived, he’d never fly again. Saburo Sakai survived. He lost most vision in his right eye permanently. He spent months recovering, but by 1944, he was back in combat, flying oneeyed in a zero over Eoima.

The war ended in August 1945. Sakai retired from the Navy and returned to civilian life. He married, started a printing business, hired fellow veterans who couldn’t find work. He became a devout Buddhist and vowed never to kill another living thing, not even a mosquito. For decades, Sakai carried the memory of that day over Guadal Canal.

In the 1970s, something unexpected happened. Sakai’s autobiography, Samurai, was published in English and became popular in the United States. American pilots and historians read it. Veterans reached out to him. In 1970, Sakai attended a meeting of the American Fighter Aces Association in San Diego. He was the only Japanese pilot there.

An American P-51 Mustang ace approached him through a translator. “Please tell Saburro that I read his book twice,” the American said. The feelings that he described were the same that I felt in combat, and I am glad that we can share that understanding. That encounter changed something for Sakai. The Americans didn’t see him as an enemy.

They saw him as a fellow pilot who’d experienced the same fear, the same adrenaline, the same impossible situations. In the early 1980s, a historian named Henry Sakaida began researching the August 7th, 1942 engagement over Guadal Canal. He identified the SBD gunners who had nearly killed Sakai. One of them was Harold Jones.

Sakaida arranged a meeting in 1983 near Los Angeles. Saburro Sakai and Harold Jones met for the first time since that day 41 years earlier. Sakai brought a gift, his leather flying helmet, the one he’d worn on August 7th, 1942. It still bore the bullet hole from Jones’s shot. A30 caliber round had passed through the helmet just above the right eye, exactly where Sakai’s wound had been. Jones examined the helmet.

The evidence of his marksmanship was undeniable. He’d hit Sakai in the head from a moving aircraft while being attacked by cannon fire from a Zero. The two men shook hands, exchanged stories. Sakai explained his epic flight back to Rabul. Jones described watching the Zero climb away, believing he’d killed the pilot. They discovered mutual respect.

Both were professionals who’d done their jobs. No hatred, no bitterness, just two men who’d faced each other in combat and survived. They became friends, corresponded occasionally, appeared together at veteran gatherings. Years later, when someone asked Sakai about meeting the man who shot him, he responded simply, “To me, the war was never personal.

” Saburo Sakai spent his final decades as a peace advocate. He spoke at schools and businesses in Japan. His message was always the same, never give up. The same determination that kept him flying 560 mi with a bullet in his head became his theme for civilian life. He visited the United States multiple times, met former adversaries, attended military reunions.

He worked briefly as a consultant for Microsoft’s combat flight simulator 2 video game, bringing authenticity to the aircraft handling. In his later years, Sakai attracted attention for publicly criticizing Japan’s inability to accept responsibility for starting the wars in Asia and the Pacific. This made him unpopular with some Japanese veterans, but he stood by his position.

On September 22nd, 2000, Sakai attended a formal dinner at Atsugi Naval Air Station as an honored guest of the US Navy. During the event, he suffered a heart attack. He died that night at age 84, surrounded by American officers who considered him a friend. Few Japanese veterans attended his funeral. Many resented his friendly relations with former enemies and his criticism of Japan’s wartime actions.

Harold Jones outlived Sakai by several years, passing away in 2008 at age 88. The friendship between Sakai and Jones represented something important. Two men who tried to kill each other in 1942 shook hands in 1983 and found common ground. They recognized each other as professionals who’d done their duty. No malice, no grudges, just mutual respect between warriors.

So Burroskai’s story reveals something about the nature of combat and the men who fight. The conflict wasn’t personal. He didn’t hate Americans. Harold Jones didn’t hate Japanese. They were both doing their jobs under impossible circumstances. Sakai made a critical mistake attacking those dive bombers from behind, and it nearly cost him his life.

But his determination, flying 560 mi half blind and bleeding, demonstrated exceptional courage and skill. His survival against those odds earned respect from both sides. American pilots who read his autobiography recognized a kindred spirit. They’d felt the same fear, made similar mistakes, experienced the same split-second decisions that meant life or death.

The friendship between Sakai and Jones proved that enemies in war don’t have to be enemies in peace. They could meet decades later, acknowledge what happened, and move forward with respect rather than hatred. Sakai’s postwar message, never give up, came directly from his wartime experience. Combat creates adversaries, not eternal enemies.

The men who fight can recognize each other’s humanity once the fighting stops. Sabura Sakai and Harold Jones proved it. One bullet, one impossible flight, 41 years, and finally a handshake between two men who’d faced each other when death was the only likely outcome, and both walked away.

News

CH2 . German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts.

German Pilots Laughed At The P-51 Mustang, Until It Hunted Their Bombers All The Way Home… March 7th, 1944, 12,000…

CH2 . America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped as North Korean fighters strafe the runway, destroying transports one by one. Enemy armor is twenty miles away and closing. North Korean radar picks up five unidentified contacts approaching from the sea. The flight leader squints through his La-7 canopy.

America’s Strangest Plane Destroys an Entire Army… June 27, 1950. Seoul has fallen. At Suwon Airfield, American civilians are trapped…

CH2 . Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above Cape Bon, Tunisia.

Germans Could Not Believe When Americans Shot Down 70 Planes In 15 Minutes… April 18th, 1943. Approximately 1500 hours above…

CH2 . Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles northwest of Lelay, New Guinea. The oil blackened hand trembled as a Japanese naval officer gripped the splintered remains of what had once been part of the destroyer Arashio’s bridge structure. His uniform soaked with fuel oil and seaater, recording in his mind words that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

Japanese Were Shocked When Americans Strafed Their 3,000 Convoy Survivors… March 3rd, 1943, 10:15 hours, Bismar Sea, 30 nautical miles…

CH2 . Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on April 18th, 1942 fundamentally altered the Pacific Wars trajectory, forcing Japan into a defensive posture that would ultimately contribute to its defeat.

Japanese Never Expected Americans Would Bomb Tokyo From An Aircraft Carrier… The B-25 bombers roaring over Tokyo at noon on…

CH2 . German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of December 1944, the German war machine, a beast long thought to be dying, had roared back to life with a horrifying final fury. Hitler’s last desperate gamble, the massive Arden offensive, known to history as the Battle of the Bulge, had ripped a massive bleeding hole in the American lines.

German Panzer Crews Were Shocked When One ‘Invisible’ G.u.n Erased Their Entire Column… In the frozen snow choked hellscape of…

End of content

No more pages to load