The Boy Outside the Children’s Hospital

It was the kind of cold that made breath show and fingers sting. People flowed in and out of Birmingham Children’s Medical Center with coffees and clipped footsteps, eyes fixed on elevators as if they could outrun whatever brought them there.

One person didn’t move.

He sat on a flattened cardboard box near the revolving doors, a weather-beaten notebook balanced on his knees. His coat was a size too big. One boot wore a band of duct tape across the toe. A red knit beanie sagged over his eyebrows. Every now and then, he looked up and watched people pass: doctors in white coats, nurses in scrubs, parents with overnight bags, kids with stuffed animals. Always watching. When no one needed anything, he drew.

The badge clipped to the hospital volunteer’s vest said his name was not on file. Most folks assumed he had someone inside. Some guessed he was waiting for a ride. No one asked too many questions in a place like that. He didn’t beg. He smiled when spoken to. Eventually the security guards stopped shooing him. He wasn’t doing any harm.

He was there most Saturdays.

Across the street a dark silver Range Rover hovered by a fire hydrant. Engine running. Heat fogged the glass. In the driver’s seat sat Jonathan Reeves—late forties, the kind of handsome you didn’t notice on first glance because exhaustion had flattened the edges. His collar was wrinkled. His tie was loose. Once upon a time, the car had been a joy. Now it was just a shelter on wheels.

In the back, tucked into a booster seat and a pink blanket, his daughter Isla stared out the window. Six years old. Brown curls tucked behind one ear. Awake, but quiet.

The accident had turned their lives into a before and after. One minute she was climbing the oak tree in the yard, racing her cousins to the fence. The next, the world narrowed to specialists, machines, and a language he hated: incomplete injury, long-term prognosis, managing expectations.

Jonathan lifted her carefully. She weighed less than she should have. He carried her toward the doors, eyes fixed on the gleam of the floor. He didn’t see the boy on the box.

The boy saw him.

“Sir,” the boy said, voice soft and serious. “I can make your daughter walk again.”

Jonathan stopped. Not because he thought it was a joke, but because of how the boy said it. Not like a trick. Like a truth.

He turned. “What did you just say?”

“I can help her,” the boy repeated. “I can help her walk again.”

“That’s not funny,” Jonathan said. He could feel the flare of anger under his ribs, hot and stupid. He swallowed it and walked inside.

Through the neurology wing and back again, in and out of consultation rooms that smelled like lemon wipes and plastic, he said all the right things: Thank you, doctor. We’ll keep up the exercises. Yes, we understand. He watched Isla squeeze the therapy putty with a little frown of concentration. He watched the therapist say, “Amazing effort, sweetie,” with her gentle voice and the kind pity in her eyes. He watched the cursor of his own life blink on a screen that no longer made sense.

On the ride down in the elevator, the boy’s words came back, as stubborn and soft as a heartbeat.

I can make your daughter walk again.

By early afternoon, the sun shoved its way through the clouds. The cold stayed sharp anyway. He carried Isla out, holding her the way you hold something precious and too breakable, and only then saw the boy again, still on the box, notebook on his lap. It should have been ridiculous. It should have been nothing. But the boy was looking at him like he’d been waiting for him to turn.

“You again,” Jonathan muttered, walking over because—God help him—he couldn’t not. “Why would you say that? You think this is funny?”

The boy shook his head. “No, sir.”

“You don’t even know her,” Jonathan said, easing Isla into the car, tucking her blanket in.

“I don’t have to know her to help.”

“You’re what—nine?”

“Almost ten,” the boy said. “Exactly.”

“You’re a kid with duct tape on his shoes,” Jonathan said, hearing the edge in his voice and hating it. “What could you possibly know about helping someone like my daughter?”

The boy glanced down at his notebook, thumb tracing the frayed edge of the cover. When he spoke, it was quiet and plain.

“My mama used to help people walk again. She was a physical therapist. She taught me stuff. She said the body remembers, even when it forgets.”

“So you watched her do some stretches and now you think you’re a doctor?”

“I watched her help a man walk after five years in a chair,” he said, looking up. “She didn’t have machines. Just her hands, patience, and faith.”

Across the entrance a nurse wheeled a laundry cart. She waved at the boy. A janitor pushed a dolly of boxes. He nodded. The boy lifted his chin slightly in return.

What did it cost to humor a kid? An hour. An afternoon. A piece of pride.

“I’m not giving you money,” Jonathan said.

“I didn’t ask for money,” the boy replied.

“Then what do you want?”

“Just an hour,” the boy said. “Let me show you.”

“Tomorrow,” Jonathan said, before he could think about it too long. “Harrington Park. Noon. Don’t be late.”

“I won’t,” the boy said.

He didn’t.

Harrington Park was the kind of place that didn’t get its grass cut often enough. Two swings with chains that squeaked. A cracked basketball court. A picnic table somebody had painted sky-blue a few summers ago. No one noticed if you cried there. No one minded if you stayed.

The boy was sitting on the bench by the oak when the Range Rover pulled in at 12:07. He stood, tucked the notebook into his bag, and smiled at the girl.

“Hi, Isla,” he said.

She blinked and smiled back. “Hi.”

“How do you know her name?” Jonathan asked, wheeling the chair closer.

“You said it yesterday,” the boy said. “I remember stuff.”

“What’s your name?” Jonathan asked.

“Ezekiel,” he said. “Zeke.”

He opened the small gym bag at his feet and pulled out a folded towel, a tennis ball, a jar of cocoa butter, and a cloth-wrapped bundle that steamed faintly when he untied it. The warmth drifted up into the cold air like a promise.

“What is all that?” Jonathan asked.

“My mama’s,” Zeke said. “The rice is for heat. Helps loosen tight muscles. The ball is for pressure points.”

He looked at Isla. “Can I work with your legs a little? Nothing will hurt. If anything feels weird, you tell me stop and I stop.”

She looked at her father. He nodded, cautious. “Go ahead,” he said.

Zeke rested the warm rice pack across Isla’s thighs. “Too hot?”

“No,” she said. “It feels good.”

“Okay,” he murmured, and waited. The boy’s patience had a weight to it. He did everything as if he had all the time in the world.

He rotated her ankles gently, as if reminding them they existed. He tapped below the kneecap. “Feel that?”

Isla shook her head.

“That’s okay,” he said, with a calm that didn’t flinch. “We keep asking.”

He worked like that—slow circles at the hip, careful pressure at the hamstring, a little massage at the calf. He talked, too, not about injury or nerves, but about cartoons and pizza and what color the sky would be if you could paint it any color at all.

“My mama used to take me with her to shelters,” he said, eyes on Isla’s leg. “Veterans. People who didn’t have money for therapy. She said you don’t need fancy to be kind. Sometimes you just need attention.”

“Your mama teach you this?” Jonathan asked.

“She taught me to see,” Zeke said. “That’s the most important part.”

After thirty minutes, he tapped Isla’s shin again. “Anything?”

“Maybe—” she whispered. “Like pressure.”

Jonathan swallowed. Hope was a dangerous thing to let out. It didn’t fit neatly back in the box once you let it breathe.

“It takes time,” Zeke said, packing up the towel. “But your muscles remember. We’re just reminding them.”

Jonathan reached into his coat, pulled out a bill, and held it out. Zeke took a step back and shook his head.

“I’m not doing it for money,” he said.

“Then why?” Jonathan asked. He asked it like a man asks a stranger standing on a bridge.

“Because she smiled,” Zeke said simply.

They met again the next Sunday. And the next. And the one after that.

The routine became a thing you could lean on: warm rice, gentle stretches, toe flexes. Some days the only victory was laughter. Some days even that felt too far.

On the fourth Sunday, victory watched from a distance.

Isla’s eyes were red from Friday. Jonathan’s jaw was clenched so tight it ached. As soon as the chair rolled onto the grass, she crossed her arms and turned away.

“Not today,” she muttered. “I tried and nothing happened. It’s stupid.”

Zeke nodded, as if she’d told him the weather.

“You think I don’t get tired?” he asked. “You think I didn’t sit in a shelter and cry when my mama couldn’t afford medicine and I had to watch?”

She kept her face turned, but her eyes slid to his.

“You’re allowed to be mad,” he said. “I get mad. But if you stop now, the part of you that wants this might stop trying too.”

Her voice was barely a thread. “I’m scared.”

“So am I,” he said cheerfully. “You know what scared means?”

“What?”

“Close,” he said, grinning. “Scared means you’re close.”

She wiped her face with the back of her hand. “Okay,” she whispered. “Let’s try.”

They did. Quietly. No speeches. No drama. Zeke steadied the knees. Jonathan lifted under her arms. She stood again. Longer this time. Shaking like a sapling in wind, but up. When he let go, she stayed.

“Again,” he said softly.

She took a step. Then another. Fell into her father’s arms and laughed like it didn’t hurt.

Everything in Jonathan’s chest rearranged. For months, he had been living inside a glass box. Grief pressed flat against every wall. That sound cracked it. The world rushed in.

Kindness is louder than you think when it’s repeated. Word of Isla’s progress traveled through Birmingham like heat through a vent.

A nurse walking her dog saw Zeke at the park with a girl who used to stare at the hospital ceiling like it was the sky and stopped to watch him turn gait into a game. She told her sister. Her sister told a therapist. By the following week two families were waiting by the oak tree.

“Can you help my son?”

“Our daughter had a stroke.”

“We heard that there’s a boy…”

Zeke glanced at Jonathan.

“You don’t have to,” Jonathan said quietly.

“I want to,” the boy said.

He taught what his mother had taught him: heat, patience, pressure, persistence. He showed parents how to roll a tennis ball under a foot to coax the brain into remembering it owned that limb. He showed them how to celebrate a twitch like a marathon medal.

Pastors dragged folding chairs across the grass. Someone from the diner down the block started dropping off bagels and coffee. An older couple arrived with a crate of rice. A kid from down the street brought his speaker and asked if they needed music. That Sunday the park sounded like hope learning to speak.

A reporter from the Birmingham Sunday Post turned up one afternoon with a notepad and decent questions. Jonathan pulled Zeke aside.

“You okay with this?”

“As long as it’s about them,” Zeke said, nodding toward the families. “Not me.”

The article ran on page two. No last name. No address. Nine-Year-Old With a Gift Helps Dozens Heal in a City Park. The photo showed the boy’s hands wrapped around a knee that wasn’t his and a girl smiling at something you couldn’t see.

A nonprofit called. A doctor called. A retired PTA mom called and said, “Some of us knit. What do you need?”

Jonathan did something he hadn’t done since before the accident. He invited someone to stay. He put clean sheets on the guest bed and set a glass of water on the nightstand like it had been waiting there this whole time. When Zeke arrived with a threadbare backpack and a blanket folded like a flag, Jonathan opened the door and said, “Right on time,” and meant more than one thing.

That night, after dinner, while Isla sprawled on the rug coloring three different suns, Jonathan leaned on the counter and regarded the boy pouring cereal.

“You ever think about going back to school?” he asked.

“Sometimes,” Zeke said.

“You’re sharp. You could go as far as you want.”

“I want to do what my mama did,” Zeke said. “Help people walk.”

“Then we’ll help you get there.”

Zeke’s grin came quick and crooked. “Okay.”

On the ninth Sunday a thing happened that will be told at cookouts and graduations and wedding toasts when they talk about who she is and where she came from.

It was warmer. Trees swayed. An audience of strangers who had stopped being strangers gathered in a loose ring around the towel in the grass.

“Same as before,” Zeke said. “We help you stand. You do the rest.”

Jonathan slid his hands under his daughter’s arms. Zeke braced the knees.

“One…two…three,” the boy whispered.

She rose. Wobbled. Breathed.

Jonathan let go first. Then the boy.

She stayed.

She took a step. The park held its breath. Then another. Then a third, because she was six and brave and didn’t know how to be afraid yet.

Then she fell, and they caught her before she hit the ground. Her laugh this time might have been the loudest sound Birmingham heard that day.

There are people who will tell you miracles don’t look like anything. They’re wrong. Sometimes they look like a boy in duct-taped boots kneeling on a towel in a park. Sometimes they look like a father letting go. Sometimes they look like a town that stops and decides—even for a few hours each Sunday—to be a family.

It kept going. New families came. Old families stayed. The pastor called it church. The doctor called it community. A PTA mom called it her favorite thing to do on Sundays now. The kids called it class.

No one put a name on the boy’s gift that felt bigger than any you could hold.

Months passed. The Reeves front yard gathered scuffed soccer balls and chalk drawings and a second-hand grill. Zeke did his homework at the kitchen table after tutoring. He put his badge from the children’s hospital—the one with his name not on file—in a drawer next to the list of Latin verbs he was trying to memorize.

Jonathan sat on the porch one night and looked at the slice of moon balancing on the edge of a tree and thought, We are different people than we were before. He didn’t mean happier, exactly. He meant more alive.

He did a thing he hadn’t let himself do since the accident. He imagined a future and filled it with bodies moving under their own power.

In that future a man tells a story: “What would you do,” he asks, eyes squinting at the memory he can’t quite wrap his hands around, “if a nine-year-old kid in duct-taped boots claimed he could heal your child?”

He lets them laugh. He lets them shake their heads.

“And he was right.”

Not everyone has degrees, diplomas, credentials. Not everyone has parents or good luck or the kind of story that earns applause.

Some people have a gift and a reason to show up anyway. Some learn to be useful before anyone calls them important. Some remember what the world forgets—that we are built to help each other stand.

If you know a kid like Zeke or a girl like Isla, tell them: You matter. You’re needed. Your body remembers. We’ll be here while you try.

News

“Sir, I Can Make Your Daughter Walk Again”, Said the Beggar Boy – The Millionaire Turned and FROZE!

The Boy Outside the Children’s Hospital It was the kind of cold that made breath show and fingers sting. People…

“Sir, I Can Make Your Daughter Walk Again”, Said the Black Beggar Boy – The Millionaire Turned and FROZE! A wealthy father had given up hope after countless treatments failed to help his young daughter walk again. But then came an unexpected voice—one he didn’t see coming. A 9-year-old boy, worn down by life but full of quiet conviction, made a bold promise: “I can help her walk.” What started as an unbelievable claim outside a hospital became something no one could explain, but everyone could feel. This is the true story of patience, loss, and the kind of healing that doesn’t come from machines—but from heart.

The Boy Outside the Children’s Hospital It was the kind of cold that made breath show and fingers sting. People…

SATURDAY, 9:12 A.M., BIRMINGHAM. A KID IN DUCT-TAPED BOOTS SAID HE COULD MAKE MY DAUGHTER WALK, NO…

The Boy Outside the Children’s Hospital It was the kind of cold that made breath show and fingers sting. People…

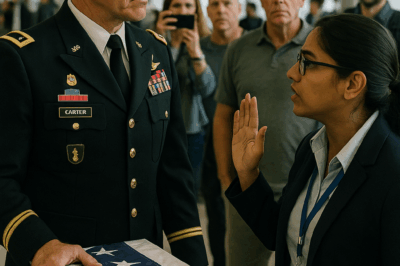

He Was Escorting a Fallen Soldier—The Airline Tried to Stop Him. Big Mistake.

“It’s just policy.” Colonel David Carter had heard those words used as a shield, as a blade, and as an…

He Was Escorting a Fallen Soldier—The Airline Tried to Stop Him. Big Mistake. Colonel David Carter, a highly respected U.S. Army officer, was on a mission of honor—escorting the remains of a fallen soldier home. But when he arrived at the airport, the airline staff refused to let him board. No real explanation, just vague excuses about “policy” and “security concerns.” Meanwhile, other passengers passed through without issue. People in the terminal started watching. Recording. Questioning. One by one, voices spoke up, including a retired Marine who refused to stay silent. Within minutes, the story was all over social media, and the airline had no idea what was coming next. As outrage spread, the military got involved—and the airline quickly realized their mistake. What happened next shocked everyone, leaving the company scrambling to control the damage. But some mistakes can’t be undone.

“It’s just policy.” Colonel David Carter had heard those words used as a shield, as a blade, and as an…

I WALKED INTO CONCOURSE C IN DRESS BLUES. ESCORTING A FLAG-DRAPED CASKET, THEY SAID “POLICY,” NO…

“It’s just policy.” Colonel David Carter had heard those words used as a shield, as a blade, and as an…

End of content

No more pages to load