THE BOTTLE

On the morning of my sixty-eighth birthday, a package sat on my kitchen table like a guest who’d arrived early and refused to speak. No card. No return address. Just a plain white envelope taped to the side and, inside it, two careful words in blue ink:

Happy birthday.

I knew the handwriting. I would have known it if I’d only ever seen it in smoke. My son’s hand—Ethan’s—after three years of silence.

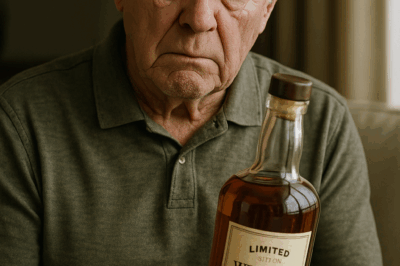

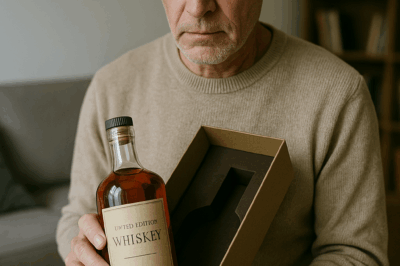

The bottle itself was a small work of art: deep-green glass with gold lettering, a wax-dipped cork, the sort of limited-edition whiskey you keep on a high shelf and point to when company asks. Once upon a time I’d have poured a single finger at the end of a long day and let it warm me from the ribs out. That ended the night a clot clamped down hard and a doctor told me, in the flat language of men who deliver unwelcome news for a living, that my heart and liquor were through.

Ethan had sat in that hospital chair, jaw moving over nothing, thumbs flicking across his phone. I told myself he was distracting himself from fear. These days, I’m not sure what I tell myself about anything where Ethan is concerned.

We didn’t have a big break, he and I. No slammed door. Just a slow drift: one Sunday dinner skipped, then Thanksgiving, then the second Christmas without him, and one morning I realized we weren’t talking at all. Silence becomes a habit—first a coat, then a skin.

I slid the bottle across the table like I was moving a piece on a board game and went back to my coffee. The clock over the stove ticked like a metronome no one could hear but me. And then I thought of Robert Carson.

Robert is the sort of neighbor who never shows up without a tool in his hand or a plan in his pocket. Two summers back, after a storm peeled half the shingles off my roof, he was up a ladder by eight with a hammer before I’d finished my first cup. When his wife, Linda, had COVID, I brought them soup every other night. If anyone deserved something decent, it was Robert.

By mid-afternoon, the whiskey rode shotgun in the old Chevy, buckled like a nervous passenger. The fields along County Road 6 were shaved to stubble, and the light had turned that particular shade of October amber that makes even a ditch look noble. Robert opened the door in sawdust and flannel, eyes going straight to the bottle.

“From Ethan,” I said. “Figured you’d appreciate it.”

His grin was pure boy. “This is the kind of bottle you make a night special for.”

“Then make tonight special.”

On the drive home, I told myself not to think about why Ethan would send me something he knew I couldn’t use. Not everything needs a reason. That was a lie I could feel my bones reject as soon as I tried it on.

The phone rang after dark. I almost didn’t recognize his voice—it had smoothed out over the silence.

“Dad,” Ethan said. “Happy birthday. You get my gift?”

“I did.”

“Well? What do you think?”

“It’s a nice bottle.”

“Did you try it yet?” A flinty edge there, barely an edge. But I felt it.

“No. I gave it to Robert.”

Nothing on the line at first. Not static or dropout. Absence, as weighty as a person. Then a measured breath. “You gave it to Robert.” Flat as a tabletop. The line clicked dead.

I stared at the receiver awhile, then put it back in its cradle. The house was quiet in that deep way old houses get, as if they’re listening for something themselves.

I woke up to the second ring the next morning—Linda Carson’s voice pulled tight. Robert had collapsed. The doctors were talking about plant toxins. Poison.

Time does an odd thing when the world on the other end of a phone gapes open. I stood in the kitchen, the October light suddenly gray and useless. Then I remembered the mason jar—I’d poured a splash from the bottle to taste for old time’s sake when I’d gotten it, then stopped myself and dumped the glass down the sink. Out of habit more than intention, I’d decanted the rest of that splash into a jar and stuck it in the fridge behind the milk.

On the counter near the trash was a small white plastic vial, the kind vitamins come in. No label. A dusting of powder clung to the inside. I didn’t remember throwing it away. I did what you do when fear needs a task: I called Gary.

Gary and I had served together. These days he runs a small veterinary lab. He owes me for a winter I pulled him out of a ditch. I brought him the mason jar in a paper bag; he met me in the parking lot with his lab coat over a sweatshirt and took it without asking questions. He called the next day, and his voice was careful as a man carrying a sleeping child.

“Frank, you’re not gonna like this. It’s white snakeroot. Enough to drop a man with a bad heart.”

My eyes closed on their own. “Robert drank it,” I said.

“You didn’t.”

“No.”

He let out a breath that sounded like relief wrapped in guilt. “Then you dodged one.”

I thanked him, hung up, then went to the trash. The vial was gone.

No forced entry. Deadbolts set. Windows latched. No spare keys under rocks or mats. But I know my own house the way a carpenter knows the bones in his hand. Someone had lifted the bag and set it back wrong.

I sat down with a legal pad, drew a line, wrote What I know on one side, What I can prove on the other. Under know: Ethan sent the bottle. Ethan asked if I’d tried it. Ethan’s tone changed when I said I’d given it to Robert. Gary found snakeroot. The vial is missing. Under prove: Gary’s report. The jar in my fridge. My own ridiculous instinct turning to stone.

Some bridges don’t appear because you want them. You build them. I pulled an old digital recorder from the drawer and slid it into my jacket. Then I drove to Ethan’s.

His house looks like all the others in the development—vinyl siding, exact lawn, lights that know when to turn themselves on. He answered the door like a man expecting a package, not his father.

“This is unexpected,” he said.

“Is it?”

We stood in the kitchen with its lemon smell and its three neatly lined bottles on the counter. None of them the one I’d given him. None open.

“You try the gift yourself?” I asked.

He laughed lightly. “The point was for you to enjoy it.”

“You know I don’t drink.”

“People change.”

I ran a finger along the rim of a clean glass by the sink. “Robert liked it. Said his favorite single malt is the one off the middle shelf.”

He blinked too slow. “Yeah.”

“Funny,” I said. “I never told you where it was stored.”

Something in his face froze, the sort of animal stillness between twig snap and run. Then he shrugged. “You must have. You get chatty when you’re sentimental.”

“I didn’t,” I said, and held his eyes until either I blinked or he did. He looked down and dried an already dry glass.

“I’m going to ask you a question,” I said. “And I’m going to let the silence afterwards answer it.”

He squared himself as if we were playing chess. “Okay.”

“Did you tamper with that whiskey?”

Silence. Clean. Heavy as a dropped hammer. The refrigerator hummed. A car rolled by outside. He didn’t speak.

“Goodbye, Ethan,” I said.

“Dad,” he called after me. The word was a hook and a warning. “You keep accusing me, you’ll push me away.”

“I’m not accusing,” I told the open door. “I’m collecting.”

Detective Reyes at the station looks like a man built for steadiness—tie straight, hair straight, gaze straight. He didn’t ask for theories. He asked for dates, times, words. He took the mason jar, made a copy of the audio I’d recorded, photographed the scuff on my front door strike plate where a key that wasn’t mine had worried the metal, and sent the liquid to the state lab.

“Don’t meet your son,” he said. “If he shows up, call us.”

That night, I pulled the old fireproof box from the hall closet and started a stack of index cards: Gary confirmed poison. 8:43 a.m. Ethan texts: “We need to talk.” Handwriting on note matches Ethan’s. Evidence becomes less slippery when you pin it with a date.

They served the warrant on a thin morning. I parked two blocks down. Reyes and two uniforms went up the walk and knocked. My son opened the door. There was a conversation. Then the door swallowed them all.

They carried out three mason jars later that hour, each labeled in masking tape in Ethan’s angled scrawl: WSR (dried roots), root stock (more dried plant), and tincture—liquid. They found a notebook, pages dented by a hard hand, dosage notes coded with triangles and asterisks. On one page: Test — △ — RC. Two pages on: FD with no triangle, just a solid number large enough my stomach turned. Next to it, a drawing of a tree with the roots circled. In his garage, next to the jars, they found handwriting about “first pour” and “heart condition.” Somewhere, a burner phone logged texts to a contact labeled RC that wasn’t Robert at all but an accomplice two towns over, a cousin with a landscaping business and enough arrogance to think “herbal extraction” stayed on the right side of the law.

Ethan wasn’t home during the search. They picked him up that afternoon without incident. He asked for a lawyer and stared through me in the courtroom the way a man stares through a window to check the weather and decides he doesn’t care.

Caldwell—slick, silver-haired—tried to buy him air with a plea. “Careless, not malicious,” he said. “A mishandled bottle. Family discord. Let’s spare everyone a spectacle.”

But a notebook isn’t carelessness. You can’t write FD — lethal in your own hand and call it an oops.

The trial wasn’t flashy. The evidence laid itself down like lumber. Reyes read aloud the text: Make sure he gets it all in the first pour. Won’t take much with his heart. Gary walked the jury through the poison. Robert held himself up on a cane and told them about bitterness in his mouth and waking in a hospital thinking his heart had finally finished its long work.

When they brought me up, Caldwell tried to make me look like a bitter old man with an ax so dull all I could do was wave it around. “Isn’t it true,” he asked, “that you sold the farm without consulting my client?”

The judge sustained the DA’s objection, but the arrow had left the bow. I told the truth anyway—about birthdays and bottles and a son who went still when silence held a question out to him.

They tried to throw dirt with a hired handwriting analysis, but the soil only clouded for a second before the stream ran clearer. The jury went out, came back, and said guilty in a voice that was quiet, not triumphant.

Twenty-five years. Fifteen without parole. I watched them lead my son away, and for the first time since he was born, I couldn’t guess what he’d be like when I saw him next.

Afterward, people wanted to say the right words. You did the right thing. You saved Robert’s life. You saved your own. All of it true and none of it filling the hollow place where a particular kind of fatherhood had lived and died.

Weeks cooled into winter. Robert came home, thinner but game as ever. He keeps a stack of magazines by his chair and jokes he’s switched from single malt to chamomile. Linda brings him ginger tea and knits on the porch when the sun’s out. Gary brought me the little plastic vial back in a paper bag. “As a reminder,” he said. Not a trophy.

Detective Reyes stopped by once in a jacket with creases that said fishing trip. He told me white snakeroot doesn’t just fall into a man’s lap. “Your son had help,” he said. “We’ve got the cousin, too.”

I fixed the porch swing. Took the creak out. Oil on the chains. New bolts. I sit there sometimes with black coffee and the manila envelope I labeled do not open—a collection of papers and photographs and a note I don’t read. Maybe someday I’ll burn it. Maybe I’ll leave it and let whoever comes after me decide what to do with our ghosts.

People think justice gives you peace. It gives you safety. Peace is built the slow way—daylight by daylight, door by door, card by card, deciding to pour water instead of whiskey and telling the truth even when it cracks something you thought you couldn’t live without.

On a late afternoon in January, frost on the grass, I sat on the fixed swing and raised my mug to the quiet yard. “To endings,” I said. “And whatever comes after.”

News

ON MY 68TH BIRTHDAY A BOX ARRIVED — NO CARD, JUST “HAPPY BIRTHDAY.” I KNEW THE HANDWRITING. Limited-edition whiskey. I don’t drink. I gave it to Robert, my oldest friend and then…. expected thing did happen

THE BOTTLE On the morning of my sixty-eighth birthday, a package sat on my kitchen table like a guest who’d…

My Son Sent Me A Bottle Of Whiskey For My Birthday, But I Gave Them To His FIL but….

THE BOTTLE On the morning of my sixty-eighth birthday, a package sat on my kitchen table like a guest who’d…

ON MY 68TH BIRTHDAY A BOX ARRIVED — NO CARD, JUST “HAPPY BIRTHDAY.” I KNEW THE HANDWRITING.

THE BOTTLE On the morning of my sixty-eighth birthday, a package sat on my kitchen table like a guest who’d…

“BREAKING: Phillies Karen makes public statement, plans to leave country and never come back. She claims everyone is treating her unfair.”

BREAKING: ‘Phillies Karen’ Plans to Flee the U.S.—But Is She Even Real? In an extraordinary twist to the viral “Phillies…

In an extraordinary twist to the already viral “Phillies Karen” saga, rumors are spreading that she’s made a shocking public declaration: she plans to leave the United States — and “never come back.”

BREAKING: ‘Phillies Karen’ Plans to Flee the U.S.—But Is She Even Real? In an extraordinary twist to the viral “Phillies…

In an extraordinary twist to the viral “Phillies Karen” saga, a rumor has gone fully off the rails: she’s allegedly made a public declaration that she will leave the United States and “never come back.” According to posts circulating on social media, she claimed that people are treating her unfairly and that her life has become unbearable.

BREAKING: ‘Phillies Karen’ Plans to Flee the U.S.—But Is She Even Real? In an extraordinary twist to the viral “Phillies…

End of content

No more pages to load