Part One

I stood soaked on my parents’ porch, clutching a paper bag gone soft at the corners. Inside: black Velcro sneakers—unbranded, unflashy, sturdy. Liam is seven; he still fumbles laces, curling his toes away from the holes in his old pair, stuffing tissue in like cardboard could become leather. His feet were saying what his mouth didn’t: Mom, I need them.

The house met me with its particular silence—the kind that hangs between walls long after voices stop. Mom didn’t say hello. From the kitchen: a clipped, “You’re late,” as if punctuality could redeem everything else.

Dad lowered his paper, peering over the edge with the bored scowl I memorized as a kid. “Don’t tell me you forgot the envelope.”

The bag in my hands got heavier, like it had soaked up rain and guilt. “I didn’t bring the envelope,” I said quietly.

Silence arranged itself around the sentence. Mom wiped her hands, leaned against the doorframe, and looked—not at my face, but at the bag.

“What’s that?” The warning in her tone said not to answer.

She reached out, yanked the bag from my hands, and lifted the shoes like she’d pulled something moldy from the fridge. “You bought shoes?”

“For Liam,” I said. “He needed—his old pair—”

“You selfish brat,” she hissed, flinging the bag so it skittered down the hallway and came to rest under the table, tongues lolling like tired dogs.

“We told you weeks ago your sister needs that money for her honeymoon,” she went on. “The resort wants a deposit.”

Dad folded the newspaper with careful offense—the choreography of a lecture he’d decided to give. “You always act like your kid is some prince,” he said, casual as a slap. “He’s a mistake. Like you.”

Wet hair stuck to my cheeks. My fingers were cold, but a different kind of numbness made my voice steady. “I work doubles,” I whispered. “I’ve covered every birthday, every uniform, every lunch. I’ve never asked you for anything.”

“And you still disappoint us,” Mom said, not even looking at me.

Dad stood; the paper cracked like it flinched. “She’s not family,” he muttered, walking toward me, eyes aimed at the space between my brows so he wouldn’t have to meet my gaze. “She’s an embarrassment.”

Mom moved first. The slap knocked the rain out of me harder than the storm had. My ears rang; my cheek burned. I kept my hands on the chair back—lessons learned young. Dad shoved me into the seat, leaned close with that stale, familiar breath. “We need to teach you gratitude.” The belt came out like a metronome. Not wild, not angry—cool, methodical. A chore crossed off. For buying shoes for a seven-year-old.

Afterward, Mom tossed a bag of frozen peas at my back like a kindness. “The wedding’s in a month,” she said. “Fix your face. We need nice photos.”

An hour later, I picked up the damp, stubborn shoes, found the receipt glued to the seam, and left. Iron pooled under my tongue from biting down against sound. Outside, the rain had thinned to a bright, blurring mist. At home, Liam slept on the couch, cartoon humming, one sock torn at the top. I set the shoes beside him and sat without waking him. For the first time in months, the crying came warm instead of watery—quiet, honest.

Never again, I told myself. This time the words didn’t float off; they settled. The next morning, after packing Liam’s lunch and kissing his hair and reminding him about the spelling word with the star—because, designed to trap second graders—I drove to an interview without telling anyone. Night shifts cleaning offices: empty halls, the smell of other people’s money and stale coffee. They hired me. I tucked three late shifts into my forty-five-hour week at the diner, learned to gulp water in closets, to bring life back to feet that had started to believe that ache was their purpose.

I didn’t save for Caribbean views I’d never see. I trimmed my tips and slid them into an envelope—not the kind Dad wanted. I folded it into myself, deeper each week.

Two weeks later, I went to my sister’s bridal shower because Mom texted a photo of her middle finger captioned: show up or don’t come to the wedding. I wore the black dress I wore to anything that required black. They sat me at a table by the food, far from the star of the hour and the gauzy shrine of family photos. “She didn’t even bring a gift,” an aunt said, not softly.

“For shoes,” a cousin added in the voice people save for shoplifting.

Crystal stood in a glittering white dress meant for evenings and unboxing appliances she wouldn’t use. She saw me. She didn’t bother to smile. “You can go now,” she said, loud enough for heads to turn. “This part’s for people who actually contributed.”

People laughed in that mean, jokey way. Mom glanced over with the shrug that used to mean fate—as if the world had arranged itself properly at last. I walked out, calm as a hanger.

That night, after Liam spelled because and fell asleep, I opened a notebook and wrote like I owed the future a timeline. Not just the shoes—the eighth-grade night Dad made me sleep in the yard for saying no too loudly. The honor-roll certificates Mom hid so the fridge could belong to one daughter. I printed photos: the purple half-moon on Liam’s arm from Crystal’s “oops” elbow at Thanksgiving; Christmas where my boy wore a sweater I’d knitted beside three brand-new outfits for Crystal’s dogs. I taped it all down and drew lines between the taped things until the pattern you can’t see from inside a person turned into a map.

Then I made a call and learned a number that turned rage into a tool. Pretending to be Crystal’s assistant, I asked a resort man—with that concierge voice—about the deposit for the presidential suite. “Twelve thousand dollars,” he said. “Paid in full by a check in your name.”

My name.

The world tilted. I shook so hard my phone case squeaked. At the bank, the printer spat proof: eight days earlier a transfer had gone from a joint account I’d never closed after high school—who teaches seventeen-year-olds how to end things properly? The signatures weren’t mine. The money was gone. “Your recourse is a legal complaint,” the teller said in that system-polite tone. I filed, quietly, with a lawyer who spelled dignity like strategy and nodded when I said, “No names yet.”

I called Ben next—the friend who once helped me steal the school paper back from the football team. He runs a small investigative podcast now, the kind of adult our twelve-year-old selves would admire. I sent him a blurred childhood and a crisp theft. “You’re sure?” he asked. “No names,” I said. I sent the photos anyway. He has always known the difference between a story and a grenade.

A week later, his episode dropped: a gentle title that made people press play and an outline sharp enough to make a town do math. He told a story about the cost of favoritism—pure sociology unless you’d lived in our house. The golf club that acted like God was a member stopped taking Dad’s calls. The church board chair took my parents by the elbows and said the charity event they’d run for a decade would continue—with an audit. Crystal lost a brand deal for her honeymoon blog. She cried to her followers, lashes flawless; the comments did the work family never had. Mom left a message that tried to sound angry and accidentally sounded afraid.

An invitation came addressed to Liam with a note slick with policy-flavored cruelty: He can come if you stay away. Your presence would make it uncomfortable for the real family. Liam traced the calligraphy and asked, “Mom, am I not real family?” The rings from that question will ripple for years. I told him the only true thing for both of us. “You are my entire family,” I said. “You are it.”

On the morning of the wedding—while they arranged peonies at three hundred dollars a bouquet and posted horse hooves in slow motion—I pulled the last box out of a storage unit two towns over and rolled the door down on a unit that didn’t know my name. For six weeks I’d taken a deep-breath loan, bought a one-bedroom in a small town two states away, and made it ours without telling anyone where to forward their disappointments. The carpet was new and cheap, the school a five-minute walk through a neighborhood where people waved without interrogating, and there was a back stoop facing east.

Before we drove away, I mailed three packages with no return address and everything owed.

To Crystal: her invitation torn clean, and a note in my careful print: Don’t call me family just to make your pictures prettier. Liam isn’t a prop. I didn’t add “paper is what’s torn.” I let silence be the ink.

To my mother: a framed photo of me holding Liam in the hospital—hair stuck to my forehead, eyes wild and whole. Across the glass: This was the moment I became enough. You never noticed. I imagined the frame cracking under her thumb and felt nothing.

To my father: the old shoes I’d worn scrubbing offices at 2 a.m. I tucked a note inside one: These got me out. Your fists didn’t.

Then we left. I turned off my phone. I closed my accounts. I picked up Liam from school like any Friday and drove into a future that would be exactly what we taught it to be.

Part Two

Our first morning in the new place, Liam sat cross-legged on the floor in pajamas and held the cereal box like a book, sounding out marshmallow as if he could summon them by saying it slowly. Sun crawled across the carpet into a warm rectangle; he arranged his dinosaurs in it like they were learning heat. He caught me watching and grinned, gap-toothed from recess and a misjudged turn on the jungle gym—not because anyone had taken anything. “It didn’t hurt,” he said, pleased with a pain that wasn’t made of fear. “It’s part of growing up.” I smiled back with that ache that feels like thank you.

In our new town, the names on mailboxes meant nothing to me yet, but on the second evening the woman two doors down knocked with a “just-in-case” pie and a card: Rowena, a phone number looping in ballpoint. Two weeks later Liam got the flu; a quiet man with a six-year-old of his own left soup on the stoop and texted: heat it slowly and tell him he’s a superhero. His name is Greg. His daughter, Tansy—named for a flower—climbs with a confidence I want to bottle.

The teacher who stays late on Thursdays for kids whose moms work second jobs asked Liam what he loves to read. When he said dinosaurs, space, comics, she said, “Then that’s what we’ll read until the other stuff stops being scary.” I cried behind the steering wheel—one month of courage at a time—and decided to learn the names of everyone who shows up for my son. You can build altars out of attendance.

Mom wrote once, via the diner I no longer work at—a manager with kind eyes forwarded it reluctantly. The envelope was plain. The handwriting was hers, the same loops that signed permission slips and report cards she never put on the fridge. You’re cruel. We lost everything. We lost you. You got what you wanted. Are you proud? I slid it under the lemon candle that makes the house smell like a choice, then took out the trash. Pride isn’t it. It’s cleaner than that—freedom, probably. Relief. The quiet satisfaction of stepping out of a play that never gave you a decent line and writing your own scene.

The podcast episode that used to make me nervous at bedtime became, in our new ZIP code, a document of another family’s harvest. Plant favoritism long enough and you’ll eat what you grew—loneliness, suspicion, gone friends. I let them eat in peace. We kept the gift of obscurity and wrote it into our days: not a cautionary tale here; just a Tuesday.

Money is tight in an honest way. Rent, groceries, the bus pass that glows in Liam’s hand like a ticket to independence. I still work nights sometimes—poverty steals sleep first—but the difference now is I sleep in a bed no one stands beside to collect debts, even in dreams. The diner taught me to carry five plates and balance a sixth with my heart. Cleaning taught me the dignity of getting rooms ready for people I’ll never meet. My favorite is the new job in the school cafeteria—Ms. Row told me about it after seeing me sprint between bus stops—because I get to hand Liam an apple and a joke through a window and pretend it isn’t weird.

Three months in, Liam skinned his knee on the playground. He didn’t scan the field to see who saw. He inspected the scrape like a scientist and ran again. At bedtime he told me he liked how his new shoes sounded on the sidewalk. “They sound brave,” he said. I wrote it in the notebook I keep now for things that matter. He laughed louder. He met eyes more. Sometimes he still flinched at a slamming car door, and I learned to say you’re safe as easily as good night.

Crystal’s honeymoon photos never went viral. The boutique that used to send her dresses stopped sharing links. The golf club accepted a sizable check from my parents and mailed a letter: membership would not be renewed for administrative reasons—institutions that beg for charity like to pretend they don’t need it. Church ladies whispered, then stopped. People in our old world learned what I’d always known: cruelty spoils fast when you can’t afford the fridge it lives in.

On the day of their first audit hearing, I was at the park learning tree names. Liam’s teacher mentioned a leaf-pressing project; I wanted to get it right, so I Googled bark I could see and asked the internet to be kind. A mother who had also left a family—but wears her wedding ring on a chain—walked up and said she liked my shoes. She meant I see you. We stood side by side while our kids experimented with gravity. I told her there’s a way out of houses that swear they are love. She nodded. “You don’t have to prove anything to anyone anymore,” she said, and I believed her, because the world doesn’t send you strangers with sentences like that unless you’re ready.

The packages I sent became stories my parents told to entertain the friends who remained. Dad said the shoes meant nothing because they were old. Mom broke the frame but kept the photo, not knowing what to do with the truth. Crystal resented the ripped invitation not for the paper but for its uselessness as a post. I didn’t watch. A friend texted summaries, hoping it would help me forgive faster. I told her to forgive herself for thinking forgiveness is a door that only opens from one side.

We built a community on purpose and by accident. Ms. Row taught Liam to tuck seeds into dirt without hurting them. Greg taught him to ride a bike in the lot behind the pharmacy where I fill my blood-pressure meds—needed less than before, still taken, because survival is medicinal. The single dad down the hall showed him how to fix a chain with his teeth and a swear word. I didn’t scold either of them; some words earn their keep if they get you moving.

On the first day of second grade, Liam walked into class without looking back, and then looked back anyway. I waved and cried on the bus—I am that cliché, and I’m not ashamed. His teacher sent a note stapled to his folder: L’s strengths: compassion, persistence, curiosity. I wrote them on an index card and taped it to the bathroom mirror; sometimes we forget strength isn’t a synonym for silence, and we need the reminder while brushing our teeth.

There’s a boy in his class who flinches the way mine used to. They don’t say much, but they sit together at lunch without deciding to. Last week they traded half sandwiches and declared bologna and turkey cousins. I told Liam he’d invented diplomacy. He asked if it pays. I said not in money. He said he preferred money. I said me too—and still, keep inventing.

Months after we disappeared, a man in a suit showed up at our old building wearing the look of someone who’s watched hours of empathy training videos. He asked the landlord if he knew where we’d gone. The landlord shrugged the way people do when they truly don’t—and I’d left him a card that said thank you for not telling. The man left. Another letter found the diner and came back undeliverable. The podcast aired a follow-up on the cost of favoritism, still nameless. Ben texted, you were brave. I replied, I got tired. He wrote back, same.

This is the life: Saturdays we walk to the farmer’s market and buy one too-expensive thing because ritual requires sacrifice. I say no more often so that yes means something. I still wear the cheap black dress to certain places—clothes don’t absolve, and it fits. I own new work shoes that don’t blister—black, Velcro, more comfortable than any pain I’ve excused—and I don’t wince when I take them off at night. Liam learned to tie laces this spring but insists on Velcro because “fast is a kind of beautiful.”

The last time I saw my parents was in a photo I didn’t choose—someone tagged me by accident. They looked smaller, as if resentment had gnawed their edges, holding a certificate that reads service appreciated. None of my business anymore. It used to be my whole business—managing their moods like ledgers, balancing their cruelty against the invoice of need. The quiet is expensive, but we’re paid up.

Sometimes I think back to that rainy hallway and the slap for buying shoes. I can taste metal again if I want. I remember how the belt turned time into something to endure instead of live in. Then I look up and watch Liam’s feet—whole, firm—running to the curb, checking both ways without being told, and I praise his shoes for doing what shoes are designed to do: carry a child somewhere worth going.

On our first evening in the new town we lit a candle—my grandmother taught me to tell the air we’ve arrived. I didn’t pray out loud, but I made a promise. To the girl who pressed a bag of frozen peas to a face she was told to “fix” for a wedding: I will never again let anyone invent a version of love that requires you to bleed to be respected. To Liam: I will buy you shoes before anyone’s deposit, and if choosing you disappoints people who define love by invoices and invitations, then disappointment is the heirloom I refuse to inherit.

When people ask how we did it—how we left, how we live in a place with our names on the lease and no other names on the mail—I tell the truth: we left quietly and then built loudly. We didn’t ruin anyone. We outgrew them. Distance did what shouting cannot. Success did what accusations never do. Peace did what pounding on familiar doors would not.

Liam wears his new shoes to the park, and they sound brave on the sidewalk. I wear peace, and it fits. We both have scuffs already, and that’s the point.

News

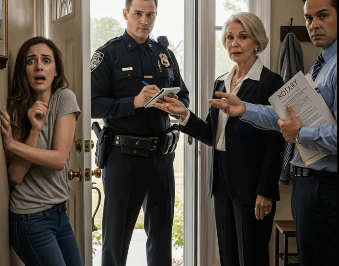

After the wedding, my daughter-in-law came to my door with a notary and said, “we sold this house, you’re going to a nursing home.” i replied, “perfect — but first, let’s stop by the police station. they’re very interested in what i sent them about you.”

Amanda stood in my living room, her smile as cold as December frost, while the notary shuffled papers like he…

I bought a house without telling my parents — then discovered they had copied my key, showed up while i was at work, and even brought a locksmith when it no longer fit.

The paper grocery bag slipped from my fingers before I could fully process what I was seeing. The jar of…

At our annual family gathering, my 6-year-old asked to play by the lake with her cousin. I hesitated, but my parents insisted. Minutes later, I heard a splash—she was in the water while the cousins laughed. I pulled her out, and she cried, “She pushed me.” When I confronted my sister, my mother defended her granddaughter and even slapped me. I stayed silent, but when my husband arrived, he made sure no one escaped accountability.

My name is Sarah, and this is the story of how one terrible day at a picturesque family lake house…

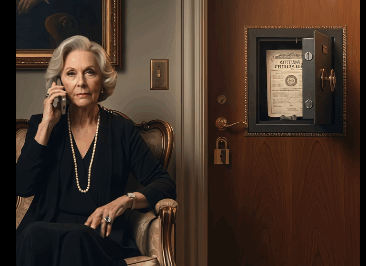

My daughter-in-law locked me in a room in my own mansion, telling everyone I was “confused.” She didn’t know the deed proving I owned the entire estate was hidden in that very room. As she hosted a lavish party downstairs, I called my lawyer. “Serve the eviction notice now,” I said. “Let’s give her guests a real show.”

When my son married Vanessa, she gradually convinced him I was becoming confused and relegated me to the guest wing…

On my wedding day, my husband pushed me into the pool—but my father’s reaction stunned everyone.

It was a Tuesday night, three weeks before the wedding, when my future was laid out for me on the…

I demanded my wife give her $7,000 maternity savings to my sister. She refused, and I accused her of being selfish. Then she broke down and handed me an envelope. “It’s not for our future baby,” she cried. Inside was the …

When I first asked my wife to give up the $7,000 she had saved for her maternity expenses, I never…

End of content

No more pages to load