neither have I.

Not in the way they want, anyway. Not in the ways that would make it easy to pretend nothing happened. People like to say time heals all wounds, but sometimes it just lets the scar knit in its own shape. You can still run your fingers over it when you need to remember where to stop.

I didn’t block their numbers. I didn’t rage-post. I didn’t send the folder to the DA. I did what I’ve always done when something breaks: I studied the pieces, decided which ones were still worth keeping, and put those back on a new shelf where I could see them clearly.

A week before Christmas, I was walking home from work—hands numb, bag heavy—when I passed a bakery window fogged with breath and sugar. There was a pumpkin pie in the display. The filling was too smooth, the crust too neat. I thought about the one I’d left cooling on our kitchen counter, Maple syrup half-teaspoon and all, and how it had sat there untouched while we rehearsed a different script.

I went in and bought a slice anyway. I ate it standing at my kitchen counter with my coat still on and my boots leaving melting commas on the mat. The pie was fine. Not mine. It didn’t need to be. It was just food. It was just me in a room full of things I paid for. That felt like enough.

Mom sent a second letter in January. Shorter than the first. We’re trying to fix what we can, she wrote. I know not everything can be fixed. I’m going to counseling. There was no ask in it, no “please call,” no “come by.” Just information, finally. I folded it and tucked it into the same drawer as the folder. I didn’t write back. Not yet. Maybe not ever. Sometimes the kindest thing you can give someone is the space to be sorry without demanding they prove it to you over and over again.

They sold the crystal dish that only came out once a year. A cousin told me in passing, like news about a neighbor’s roof. It stung for a second in an unlikely place. Then it passed. Objects were just objects. The thing I was grieving didn’t live in glass.

The seminar at the community college turned into a series. The first Saturday, a dozen people sat in plastic chairs under fluorescent lights while I clicked through slides about phishing and power of attorney and how to make noise when a banker sounds certain. The third Saturday, a man in a VFW jacket raised his hand and said, “What do I do when it’s my son?” He didn’t cry when he said it. He didn’t have to. I showed him how to print a transaction log, how to ask for camera footage, how to say the words “I need to speak to your compliance officer” without swallowing them. I watched his shoulders drop a quarter inch as the sentence left his mouth. Sometimes relief is just a verb pronounced correctly.

Theo asked if I wanted to join the elder fraud task force. It meant more hours, more cross-agency meetings, more days spent in rooms where people assumed I was the assistant until I started talking. I said yes. At night I read case files with a mug of tea sweating onto a coaster and a pen circling numbers that shouldn’t have matched but did. There was comfort in it: the way math told the truth even when people didn’t.

In March, I found a new apartment. A one-bedroom with a crooked hallway and a window that framed the Charles like a screensaver. The landlord seemed surprised when I said I wanted a place with a dining table. “Most people just eat on the couch,” he said. “Most people aren’t me,” I said, and signed anyway. On moving day, a friend from work carried a box labeled COOKBOOKS up three flights without complaining. I gave him the good beer and didn’t apologize for the weight.

I bought a table secondhand—solid wood, a scratch across the top where someone else’s Thanksgiving had gone a little wrong. I sanded it out one Saturday while a baseball game murmured in the background the way it had when I was a kid. I wasn’t trying to make the table perfect; I just wanted it to feel like it belonged to the room and the room belonged to me.

I invited people over. Not the kind of friends who perform at your parties, the kind who ask where you keep the foil and actually remember where you put the wine opener. We ate pasta off mismatched plates and argued about whether it’s acceptable to put peas in carbonara (it is, if you’re tired and like peas). When someone asked about family, I said, “It’s complicated,” and passed the bread. The conversation moved on without needing to detour through my entire history. There was a clean mercy in that.

In April, I drove back to New Haven on a Wednesday and parked two streets over. I told myself I was just going to get a box of winter clothes from the attic, but when I turned off the engine, my hands stayed on the wheel. The house looked the same from the curb: paint flaking, azaleas overgrown, the porch light fixed at the same slight angle from where Dad had whacked it with a broom fifteen years ago chasing a bat.

Mom opened the door before I knocked. She didn’t look surprised. Just older in a way that wasn’t all about her face. We stood a foot apart for an awkward beat. Then she stepped back and let me in without touching my arm.

There was no pie. There was no drama. She handed me the attic key and a stack of folded towels “just in case.” On the way to the stairs, I passed the refrigerator. A magnet held up a piece of paper—a printed list with bolded headings. Passwords. Banking. Insurance. Two-factor authenticator codes had been written down the first time ever in our house. My name wasn’t in the margin anywhere. It shouldn’t have made me feel as much as it did.

On my way out, Mom said, “Rachel.” I turned. She was holding the photograph she’d mailed me, the one with the porch and the wings and the red paint.

“I framed it,” she said, almost apologetic. “I don’t know if that’s…right.”

“It’s yours,” I said. It was the truest answer I had.

“Will you…” She stopped, started again. “Would you like to take a slice of pie? I made too much.”

My mouth did something that might have been a smile if I’d had more practice. “Maybe next time,” I said.

I carried the box to my car and drove back toward Boston with the radio low and my phone turned over on the passenger seat. It buzzed once near Hartford. I let it.

That night I put the framed photo on the bookshelf between a math textbook and a novel with a cracked spine. I didn’t hide it behind anything. I didn’t give it a shrine. It was part of the story, not the whole. I sat at my new table and ate leftovers out of a container because I was tired and didn’t feel like doing dishes. Out the window, the river moved in its patient way, taking what it could carry and leaving the rest. I ran my finger along the scratch I’d sanded out and felt it faintly anyway.

Every now and then, someone asks me if I’ll ever forgive them.

“What would that look like?” I ask back.

Sometimes they mean sit around the same table at Thanksgiving with everyone pretending it never happened. Sometimes they mean let your sister hold your niece and tell her the story about the time you fell off the back porch and chipped your tooth on the garden gnome. Sometimes they mean give the pie another chance.

Forgiveness, I’ve learned, isn’t a key that unlocks the same door. It’s a decision to build a different house.

I’ll help strangers reclaim money because they shouldn’t be punished for being loved by the wrong person in the wrong way. I’ll teach a room full of daughters and sons what to say at a bank and how to not apologize for asking for the manager. I’ll keep my folder where it is, not because I plan to use it, but because some truths deserve to sit undisturbed.

And on Thanksgiving morning, this year and maybe next, I’ll buy nutmeg deliberately and measure maple syrup in a half teaspoon that makes me roll my eyes. I’ll bake a pie. I’ll drive it exactly three hours in one direction or another, to a friend who hates cooking or a neighbor who just put their mother in hospice or that woman from my Saturday class who told me her kids all live out of state. I’ll set it down on someone else’s counter and take my coat off and say grace if they ask me to. Sometimes we replicate rituals so we can salvage the parts that still work.

I used to think home was a place where the people at the table chose you. Now I think it’s the place where you choose the people at the table.

The folder stays shut in the drawer. The pie knife migrates to the front of the utensil tray. The phone rings less. The river keeps moving.

The facts haven’t changed. Neither have I, not back into who they thought I was, not into what they accused me of. I changed in the ways I needed to: from suspect to witness, from scapegoat to teacher, from dutiful daughter to a woman who knows where to set down a warm pie and when to walk away.

News

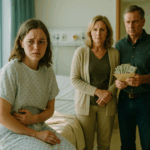

“I made the appointment for tomorrow,” Daniel said coldly, without looking her in the eye.

Sophie’s heart nearly stopped. “What date?” He didn’t hesitate. “The clinic. We agreed it was the best.” No, I wanted…

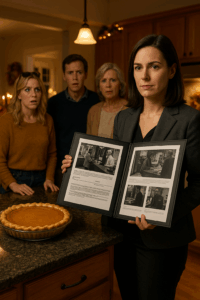

He invited his ex-wife to his lavish wedding to humiliate her—but she came back with a secret that left everyone speechless.

As the Rolls-Royce pulled up in front of the glass-walled lounge overlooking the Pacific, Brandon Carter stood tall in his designer tuxedo…

An obese noblewoman was given to an Apache as punishment by her father—but he loved her like no one else…

They called her the useless fat girl of high society. But when her own father handed her over to an…

A MILLIONAIRE INVITED THE CLEANER TO HUMILIATE HER… BUT WHEN SHE ARRIVED LIKE A DIVA!…

He invited the cleaning lady to his gala party just to humiliate her, but when she arrived looking like a…

HER FATHER MARRIED HER TO A BEGGAR BECAUSE HE WAS BORN BLIND — AND THIS IS WHAT HAPPENED

Zainab had never seen the world, but she felt its cruelty with every breath. She was born blind into a…

The Invisible Genius: How the Janitor’s Daughter Saved 500 Million Euros and Revolutionized Spanish IT

Half a billion euros were about to disappear into thin air. Spain’s most powerful computers were shutting down one after…

End of content

No more pages to load