The bench outside juvenile intake wasn’t made for adults. It was the kind of narrow, varnished plank you’d find in an elementary school hallway—good for backpacks and shoelaces, cruel to knees and pride. I sat anyway, feet flat, knees splayed, elbows braced on thighs in the same posture I use changing a tire on the shoulder of the interstate. It kept my spine from snapping.

Inside, fluorescent lights hummed. A clock over the vending machine ticked too loud, a metronome in an empty church. Somebody had taped a polite sign to the wall—PLEASE DO NOT FEED THE FERAL CAT THAT SOMETIMES ENTERS THROUGH THE ALLEY—and someone else had drawn a halo over a doodled cat and written SAINT WHISKERS in thick black Sharpie. It was the only thing that made sense.

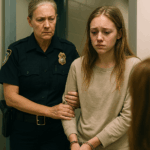

The door opened. An officer with a face like a folded paper fan led my daughter out by the elbow. No cuffs now, but red crescents around Emma’s wrists told the story, mean and precise. Her eyes were swollen, lashes spiked with tears that came in waves she couldn’t stop. Fifteen years old looks a lot like five when it’s been wrung out.

“Mrs. Dwyer?” the officer said, professional and tired. “Thanks for coming.”

“Of course.” The two words were all I could carry without spilling everything else.

She gave me the official version, voice pitched to neutral, as if reading a recipe. “Your daughter was detained at 4:18 p.m. by store security at Winthrop Jewelers for suspected shoplifting. Item: one fourteen-karat pendant necklace, retail value four hundred twenty-nine ninety-nine. She was cooperative. The responding officer transported her here.”

Emma moved like a flower listing toward light and stopped against my shoulder. I put an arm around her and felt the small tremor that had started when cold metal found soft skin. “Can I see it?” I asked. “The necklace.”

The officer flicked a thumb toward a metal desk. Evidence sat in a clear bag stamped EVID, the kind of plastic that crinkles if you breathe too close. Even through hum and antiseptic I recognized it. Not just with my eyes—my stomach recognized it. My hands did. Old muscle memory pulled tight across twenty years of Easter Sundays and clasping it around my mother’s throat because she insisted I “make myself useful.” A tiny gold circle with a scalloped edge like a coin someone glided smooth with years of touch. My grandmother’s before it was my mother’s. A family heirloom. And, apparently, a felony.

The officer slid a clipboard across the desk. “Your father gave a statement,” she said, careful. “Says he saw Emma take it off a display while the clerk was helping another customer.”

The room changed temperature. The fluorescent buzz lifted a note. Air thickened. Inside me, something else happened: a stillness, pristine and cold, like a hand pressed flat over a pond’s surface. I didn’t shout. I didn’t ask why my parents were at the jeweler’s, why my father stood close enough to issue a statement that turned my child into a suspect. I looked at the red grid impressed on Emma’s wrists and thought: So this is how far they’ll go.

“It’s not true,” Emma whispered. The words came out broken, as if each syllable had an edge. “Mom, I didn’t touch anything. I swear. I was just…looking at the little velvet stands and thinking how Grandma always—” She stopped. Her mouth sealed into a line thin enough to cut. “I didn’t touch anything.”

“I know,” I said, and then the only other thing there was to say: “Don’t worry. This won’t take long.”

The officer blinked like she’d been expecting bargaining, a scene, something messy with mops attached. Instead she got my voice the way a hallway light flips on: unambiguous. She cleared her throat. “You can sign for release. Your daughter can go home pending charging. The store is pressing.”

“Of course they are,” I said. The two-way mirror caught the ghost of my mouth and threw it back at me.

On the drive home, Emma cried until she didn’t. Tears have a shelf life. The body runs out. I watched her in the rearview mirror—cheeks raw, hands flat on her thighs like she’d forgotten what hands are for. Fifteen is learning where to put your hands when people look. Fifteen is discovering some people are watching wrong on purpose.

We passed the turn for my parents’ neighborhood. My foot wanted to floor it; the truth wanted to leap out of my ribs and blister the air. But rage is messy. Rage is obvious. I needed something else.

Precision.

Family betrayal doesn’t arrive like a crash, hood crumpled, horn screaming. It drips. It drips through holidays and inside jokes and how the knife drawer is organized. It drips in the voice your mother uses when she says, “You know your sister always had such a head for numbers,” and the voice your father uses when he says, “Emma’s so spirited,” the voice reserved for a dog that steals hot dogs from a picnic table. It drips in matching bicycles for my sister’s kids last Christmas and a sweater two sizes too big for Emma. It drips when your mother closes her purse and glances around like there are thieves in the family. It drips when your father looks at authority the way a man looks at something he invented.

I knew the drip. I knew the sound it made hitting the bucket.

At home I ran a bath and sat on the tile while she slid into water as hot as she could stand. I washed her hair like I hadn’t since she was small. When you’ve watched your child’s hands turn red around steel, you do old things with devout attention. I changed her sheets and stacked the good blanket at the foot of the bed. When she crawled in, damp and exhausted, I tucked it tight around her shoulders.

“Is it over?” she asked, voice hoarse and too small for the room.

“Yes,” I said, and meant it two ways—comfort now and verdict later.

When she slept, I watched her breathe from the doorway the way mothers do when their children are babies, counting each rise like tallying miracles. Then I went to the kitchen, brewed coffee strong enough to etch porcelain, and called a lawyer before the first cup cooled.

I didn’t hire a court-corridor cowboy or a country-club glad-hander. I hired a woman whose office sits on a second floor above a vacuum repair shop and whose reputation says she eats forged narratives for breakfast. Maria Cho opened her own door, shook my hand like a contract, and didn’t offer sympathy. She offered a legal pad.

“Tell me what you have,” she said.

I laid out the receipt my mother left tucked in a holiday cookbook—the one from Winthrop Jewelers with the last four digits of her card blacked out in a way only theater produces. I laid out a photo of my mother wearing the pendant at the Winter Gala two weeks ago, the scalloped circle gleaming under ballroom light. I read the text from my sister after a fight she’d had with our mother: She’s obsessed with that necklace. Says it proves she’s the rightful matriarch now. It was a joke when she sent it. The kind you use to wrap a wasp.

“You’re sure it’s the same piece?” Maria asked, pen already moving.

“Down to the scratched clasp,” I said. “I’ve fastened it a hundred times.”

“You think they planted it,” she said. She didn’t make it a question. She made it a room where the truth could sit.

“I think my mother slipped it into Emma’s backpack while my father watched the aisle,” I said. The words didn’t wobble. They made a clean sound when they landed. I realized, watching Maria write them, I’d been walking toward that sentence for years.

She flipped a page. “Here’s what we’re doing. We request exterior and interior footage from the store and parking lot. We schedule with the detective, we bring a packet so neat it makes the right decision easy. We don’t panic about the juvenile petition. The surest way to evaporate a bad charge is to show how heavy it is to carry. And we assume everyone in this town is either recording or will happily testify on behalf of whomever they had brunch with last. Do you understand me?”

“Yes,” I said. “I brought copies for the detective.”

Maria gave me the kind of smile you give a retriever who brings back a pheasant without mangling it. “Good,” she said. “Call him today.”

Detective Sayers had the look of a man who’d practiced not looking impressed in a rearview mirror. He was tired but not careless, skeptical but not incurious. I liked him, which didn’t matter, but made my voice steadier.

I laid out the receipt, the photo, a list of the times my parents had been in the store over the last month—the times my mother bragged about to her bridge club, which has looser lips than a frat party and a member whose granddaughter plays soccer with Emma. Small towns are tight when you stop pretending they aren’t.

“I’m not asking you to believe me,” I said. “I’m asking you to look at the film and believe your eyes.”

“Store footage is…variable,” he said.

“Parking lot’s often better,” I said, sliding a request form across.

He lifted his eyebrows, a small salute to a woman who’d already done this in her head. “We’ll pull it,” he said.

“And Detective?” I added. “False reports waste resources. I know you know that better than anyone. I’m not here to make your job harder. I’m here to give you the cleanest route to the right conclusion.”

He nodded once. “We’ll be in touch.”

In the hallway, people turned curiosity into gravity. I didn’t give them my face. They’d tell a dinner story about the woman who walked in with a folder. They’d decide if I was cold or poised, hysterical or stone. Women are graded by choreography in rooms like that. I wasn’t interested in points.

Day three: Sayers called just after seven. I put him on speaker at the kitchen table. Emma was at school, which felt like watching her cross a river on a rope bridge, but she wanted to go. My sister had stopped by with a quiche—her language for I’m here even if my spine still wobbles when Mom calls. The kitchen smelled like eggs and nutmeg and Sundays after church, and I refused to let nostalgia rearrange me.

“We have the footage,” Sayers said. “Can you come in?”

“I can,” I said. “My lawyer will be on the phone.”

He hesitated. “Ms. Cho won’t need to do much talking.”

“She’ll do as she pleases,” I said pleasantly. “We’ll be there in twenty.”

The tape on his ancient monitor had bled its colors to green, but it didn’t matter. There was my mother in her long camel coat. There was her hand—small, quick—slipping into Emma’s backpack while Emma leaned into the back seat to grab her scarf. There was my father, standing sentinel, scanning the aisle like a lighthouse that prefers to blind ships. The pendant caught one thread of sun, winked like an eye, and disappeared into the bag.

No drama, no clumsiness. Clean as a magic trick perfected on gullible relatives.

“This isn’t what it looks like,” my father would say later. He always says that when reality refuses obedience. It’s his prayer.

Sayers didn’t watch the screen while it played. He watched my face. Maybe he expected shock or grief or satisfaction. What he got was stillness again. Not numbness—focus.

“We’ll interview them again,” he said after the tape stopped. “With counsel.”

Maria’s voice was dry in the speaker. “You’ll need new forms for charges—perjury, false report, tampering, contributing to the delinquency of a minor at minimum. Given her age, I trust you’ll review endangerment statutes.”

“We’ll consider all applicable,” Sayers said.

“And Emma’s record?” I asked. “It will reflect an expunged detention with cause dismissed?”

“It will be wiped,” he said. “Formally. Permanently.”

The breath I’d been holding since the cuffs left her skin finally left me. Not in a sob. Like a winter tide pulling back—steadily, so cold it burned.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Don’t thank me yet,” he said. “Come back tomorrow at nine. They’ll be here.”

We didn’t bring Emma to the station. She’d given the system enough of her eyes and pulse. My sister promised muffins and trash TV. Their laughter spilled through the kitchen door when I zipped my coat. I stood there with my hand on the knob and thought about my parents’ door and how many times I’d left it feeling smaller, orbiting their sun at the safe distance they allowed.

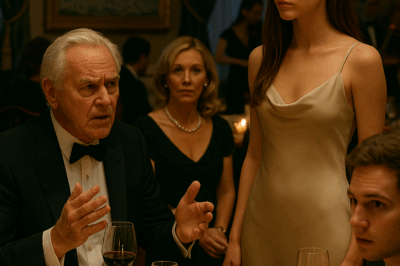

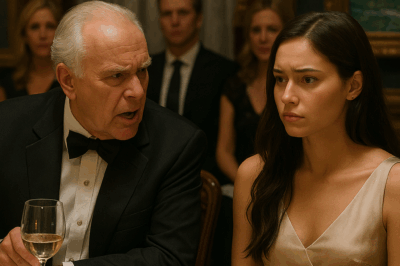

In the interrogation room, my mother wore navy and lipstick that believed in optics. My father wore his law-school tie; he never practiced, but he loved the theater. When Sayers pressed play, the oxygen in the room adjusted. In the grain, my mother moved like a woman choosing cherries. My father stood like a man sure the camera adored him.

My mother’s face emptied only when her hand vanished into the frame and Sayers—God bless whatever bureaucratic angel sat his shoulder—advanced the tape frame by frame so no one could insult him with perspective and blur. My father’s mouth opened like a man preparing to remind the world he is in charge.

“This—” he started.

“Is exactly what it looks like,” Sayers said. He didn’t raise his voice. “Mr. and Mrs. Kline, don’t.”

Maria didn’t need to talk. She sat opposite my parents, pen quiet, and let the words the state uses when it’s disappointed fall into the room with their full weight: perjury, false report, tampering, endangerment. Bricks with titles. I didn’t look away from my mother’s face when child landed. I watched lipstick crack in the middle like a road in a heatwave.

Sayers stepped out to fetch forms. “Initial here and here if you’re talking without counsel present,” he said. My father had shown up to a fire without water. He still believed gravity didn’t apply to him.

I leaned forward. I kept my voice gentle because women get graded harder when their volume rises. “You didn’t just try to ruin her life,” I said. “You tied the rope to your own necks. I only pulled.”

My mother lifted her eyes to mine and—for the first time in my life—what I saw wasn’t superiority. It wasn’t even shame. It was fear. For one second she looked like a woman my age—someone’s mother, not the sun. Then my father’s chair scraped, and the old tide came back in.

“You can’t do this to us,” he hissed. His hands shook on the tabletop. I watched the tremor like a scientist watches a beaker—curious, detached, aware the reaction was predictable.

“You already did,” I said, and sat back.

It didn’t end with a bang or a slap. It ended with film.

By evening, a friend from church texted to say the prayer chain had turned into gossip and the gossip had turned into silence and silence, around here, is a kind of shunning. By morning, the county paper called. Reputation has a half-life faster than radon when the people who mint it turn away.

At home, Emma curled into me on the couch. We watched something stupid and kind. When she asked, “Is it over?” I said, “Yes.” For her, it was true. For my parents, it was just beginning. For me, it was an ending I’d been drafting since I was fifteen: the day I stopped organizing my life around other people’s stories about me.

Three days. That’s how long it took to dislodge their legacy. I knew the rest would take longer. But I’d learned something in the room with the two-way mirror: stillness is a weapon. So is accuracy. And love—when you sharpen it and aim—is a kind of justice.

Sunday felt gossipy even in the air. Our town breathes on schedule—church, brunch, yardwork, naps—and talks while it moves. Emma wanted pancakes and normal, so we went to the diner behind the Methodist lot. If you sit in booth five you can watch hats and heels and sports coats parade by. It’s my closest thing to religion: coffee strong enough to strip enamel and the pleasure of watching pageantry from safety.

By the second pot, phones had started their Sunday dance. Heads bent. Thumbs flew. A woman from the prayer committee who once baked Emma a violin-shaped cake gave me a look that said she’d chosen a side and it wasn’t mine. I gave her the same face I give weather behaving exactly like weather: acknowledgment without surrender.

“Want a corner table?” the waitress asked while topping off our cups. She’s worked here thirty years and has a better moral compass than most sermons.

“We’re fine,” I said. Emma was spreading butter to the rim of her plate like mapping coastlines.

“You know Saint Whiskers was in the alley last night,” the waitress added, a wink toward the intake sign legend. “Left half a squirrel on the doorstep. That cat solves problems.”

“Good to know,” I said, and meant it.

On our way out, one of my father’s golf partners materialized like a stage cue. “Surely there’s been a misunderstanding,” he said, words dangling like a jacket he expected me to take.

“We cleared the misunderstanding,” I said. “The police have the tape.”

He blinked. For men like him, tape lives with VCRs and prom nights, not with footage that rearranges lives. His mouth opened. Nothing came. I shepherded Emma to the car.

“They used to clap when I played the offertory,” she said softly when the doors shut.

“They’ll clap again,” I said. “People have short memories for good and long ones for gossip. We’ll retrain them.”

“How?” she asked. Her voice broke on the H.

“Paper,” I said, turning the key. “And ash.”

If reputation is oxygen in a small town, paper is the matchbook. On Monday the first article ran online: COMMUNITY LEADERS QUESTIONED IN JEWELER INCIDENT; TEEN EXONERATED. Carefully lawyered, but accurate. It quoted Sayers. It quoted Maria with a sentence sharp as a wire. It didn’t quote me. Good. I didn’t want spectacle. I wanted accuracy to do its job.

By noon my sister stood on the porch with sunglasses and a Trader Joe’s bag big enough to feed a team. “Mom’s called me a dozen times,” she said in the kitchen. “She says she made a mistake. Says she wanted to scare Emma because you’re ‘spoiling her.’ Says Dad is handling ‘the legal side’ and I should ask you to consider the family. Her words.”

“You mean consider their reputation,” I said.

“She said if this goes on, they’ll lose everything they built. The club. The investment group. Her board. Church is already…you know. And I’m catching it, too. She wanted me to remind you we’re a family.”

“We are,” I said. “Which is why I’m doing this.”

My sister’s eyes filled. “She said I won’t get my half of the lake house if I don’t help.”

There it was. Love as ledger. “Do you want the lake house?” I asked.

“I want to stop feeling like a bad daughter,” she said.

“You’re not,” I said. “And you’re not responsible for who they turned into.” I pushed a folder across the counter. “Maria’s draft of my victim statement for the DA. Emma’s name gets sealed. Mine doesn’t. You don’t have to like it. But please don’t try to talk me out of it.”

She nodded twice—once performative, once real. Before she left she slipped a foil-covered lasagna into my fridge and a key to the lake house onto the counter. “In case you want to drive out and scream,” she said. “It’s empty in winter.”

“Thanks,” I said. I meant it.

The principal called that afternoon to “touch base,” which in administrator means “preempt liability.” He praised Emma’s grades and assured me her record would note dismissal. Then: “Kids talk. We’re addressing it.”

“How?” I said. “A general assembly about rumor?”

“A reminder of our anti-bullying policy,” he offered, the kind of document that gets stapled to a board and curls at the edges until it falls off.

“Here’s what I need,” I said. “A letter for her file stating police cleared her and any on-campus reference will be treated as harassment. And teachers need to shut it down in the room. Not with a speech— with a look and a redirect. The quiet kind. Do you understand me?”

He did. Tuesday morning the letter hit my inbox. Paper.

Maria met me at the DA’s office. The ADA—Powell, sharp-eyed—offered a cautious hand. “We’re on it,” she said. “Camera doesn’t show the inside drop. Parking lot shows the plant. Defense will try ‘retrieving what fell’ and ‘messy.’ They’ll lean on plausible.”

“Then lean back harder,” Maria said. “They filed a false report on a child. Timelines align. Initial stories don’t. This isn’t messy. It’s arithmetic.”

Powell nodded. “We’ll charge what we can charge. I don’t barter away harm to a kid because the harm-doers sit on committees.”

“Good,” I said. “We’re not in the market for mercy that looks like enabling.”

“Just so you know,” Powell added, “their attorney floated a plea: admit the false report, written apology, fine, no jail, deferred adjudication. Quiet.”

“No,” I said before Maria squeezed my knee. “They turned a child into a prop. They don’t get quiet.”

“Then we’ll see them in open court,” Powell said, as if she were placing a brick on a wall.

On my way down the courthouse steps my phone buzzed. My father. I let it go to voicemail. The transcript landed a minute later: We need to talk. You’re making a mistake. You’re destroying our family. Imagine Emma’s college application with this attached to your name. Do the right thing. I typed three drafts that would have scorched earth. I deleted them. I forwarded the message to Maria with a single line: Add to file.

At school Emma learned who her friends were. Teenagers report their homes without realizing it. Two friends showed up that first night with gummy bears, face masks, and permission for an ugly cry without commentary. One stopped replying and posted a selfie wearing a tiny gold heart with the caption some of us earn what we wear 😉. I told Emma to block anyone who made her stomach hurt. She did— a girls’ choir co-soprano, a softball teammate, a boy who used to copy her algebra homework and now thought “innocent until proven guilty” was a slogan for men with podcasts.

Wednesday, I booked her with a therapist recommended by three mothers who never agree on anything except SPF. Ms. Flores had a couch that didn’t swallow you and a way of asking questions girls will answer. Do you want to talk or sit? Plan, or feel bad on purpose for a while? Tell it as it happened, or as you think about it at 3 a.m.? Emma came out with lemon drops and homework: write a letter dated six weeks from now about one tiny thing you can do without thinking about them.

“Her handwriting is better than yours,” she told me, smiling. “Sorry.”

“As long as her plan works,” I said.

Thursday, a courier in a cheap suit delivered an embossed offer from a boutique firm: In the interest of family unity, our clients propose a trust for Emma’s education in exchange for a public statement acknowledging the incident arose from misunderstanding and a desire to keep the matter private. It smelled like panic and cologne.

Maria laughed. “They’re negotiating like this is a merger,” she said. “No.”

I looked at the number—enough for four colleges, a couple cars, and an entry-level down payment on a future my parents believe you can buy wholesale. I wrote one sentence on my stationery, sealed it, and addressed it in my own hand.

We do not accept hush money to rewrite a police report.

Paper.

Friday evening we grilled chicken because bodies insist on continuity even when heads prefer drama. The backyard smelled like oregano and smoke; chalk hopscotch sprawled on the pavers. That’s when my father came through the gate.

He didn’t knock. He never does. Old rules say this is his city and we are tenants. He wore golf clothes like his body forgot this isn’t a fairway. The air cooled by a degree. He took in the grill, the chalk, the condensation beading on plastic cups, and then he found Emma’s face in the kitchen window.

“Go inside,” I said, eyes on him.

Emma obeyed, step by step. My sister hovered in the doorway, white as stucco but still and present. She’s terrible at drawing lines and excellent at recognizing them.

“You don’t come here,” I said.

“We need to talk,” he said. “Your mother is—”

“She can send her attorney.”

“She’s sick,” he said, playing the card they always play when consequences land. “The stress—”

“Of lying?” I asked. “Of watching an entire town discover the queen’s scepter is a plastic spoon?” I shook my head. “Not in this yard.”

He stepped forward. I stepped to meet him. He had six inches and fifty pounds. He also had a lifetime of calling those inches God. I had a week of paper, a detective, and a precise idea of where my fear ended.

“You will not speak to me that way,” he said softly, the voice for judges at charity auctions and dogs who wag impolitely.

“I will,” I said even softer so he had to lean in. “And you will leave now. Or I call the police and add trespass to your file. Your choice.”

He looked past me, toward the window, trying to count all the faces he used to command. I moved to block his view. Calculation failed across his face like a short circuit. He didn’t have a move. He turned. He didn’t close the gate.

“Buy a lock,” my sister said when we could breathe again.

“Buy a fence,” I said.

“Buy a camera,” Emma said from the doorway.

I smiled. She was learning.

Saturday’s mail held a thin blue envelope—my mother’s stationery. I stood at the table holding it the way you hold a childhood photo you might not survive. I slit it clean.

Three sentences, each worse than the last: I didn’t mean to hurt Emma. I wanted to teach her a lesson about how the world works. If you’d raised her with more discipline, I wouldn’t have had to.

There are many kinds of fire. The best kind is fed with paper that used to catch your breath. I took the letter outside, fed it to the grill, and watched the words lace and blacken and release. Ash is cleaner than ink.

I snapped a photo of the last corner burning, sent it to Maria, and called Powell. “I want a restraining order,” I said. “No contact. No visits. No dropping by. If the court asks why, tell them I don’t believe in arsonists sending thank-you notes to the fire department.”

“We’ll file Monday,” she said.

“Make it loud,” I said. “No more quiet.”

The Chronicle ran a second piece—one of those humane explainers tucked under the school lunch menu: DA Rejects ‘No Admission’ Plea; Open-Court Statement Required. It was the sort of sentence that sends a specific chill up spines used to owning rooms. They printed grandparents instead of names, as policy requires until a plea or verdict. It didn’t matter. Everyone knew. My father stopped going to the club. My mother wore sunglasses in the grocery store and moved her Pilates class to the guest cottage to avoid “hostile energy.” (Translation: accountability.)

Saturday, Ms. Flores assigned “do something normal among humans.” We went to the farmer’s market. It rained the kind of rain that smells like baptisms no one asked for. We looked at tomatoes and bread and mugs we didn’t need. At the last row, Maya from Winthrop Jewelers stood under a blue tent with a felt sign: WE’RE SORRY.

“Is this tacky?” Emma whispered.

“A little,” I said. “Tacky and trying beats polished and cruel.”

Maya saw us and asked for consent before speaking—an act rarer than gold. “Can I apologize?” she said. “It won’t fix anything. We were supposed to have protocols. We didn’t follow them. I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay,” Emma said, then smirked. “Not okay okay. But thanks.”

Maya smiled at her like at an adult who gets the complicated joke. She slipped a small white box onto the table. “From our bench jeweler,” she said. “Scrap from a repair. He made a charm you can melt or keep or turn into whatever you want. He said it’s not a replacement. It’s a do-over.”

Inside lay a tiny gold bar stamped with one word: BEGIN. Not a pendant. A starting point.

Emma laughed, clean and surprised. “This one doesn’t have any stories yet,” she said. “I like that.”

“Me too,” I said.

We bought strawberries we didn’t need and a loaf of bread and left lighter than we arrived.

The court date came on pale-green card stock: STATE v. KLINE — PLEA HEARING — 10:00 A.M. I put it on the fridge with a cow magnet, next to the school letter and the market receipt with BEGIN scribbled in blue ink by a jeweler’s hand.

Powell met us outside the courtroom, hair up, files tabbed in four colors. “We expect two pleas,” she said, brisk to keep sentiment from messing with physics. “False report for both. Tampering for your mother. We pushed endangerment; defense balked; judge suggests a suspended count with conditions: apology in open court, community service not involving galas or children, letters to Emma and the store naming what they did. If they wobble, we try it.”

“What about the pendant?” Emma asked, sudden and fierce.

“It stays in evidence until probation ends,” Powell said. “Then ownership reverts to the person the court deems least likely to weaponize an heirloom.”

“Is that in a statute?” I asked, smiling despite myself.

“It is today,” she said.

We sat second row. I held Emma’s hand and unclenched my jaw one tooth at a time. When my parents entered, the temperature dropped. My father wore the law-school tie like superstition. My mother’s mouth was a straight line lipstick couldn’t soften. For a second, I saw the woman who taught me pie crust and thank-you notes and where forks belong. Then I saw the woman who slipped a necklace into a child’s bag and remembered that etiquette is the lace you lay over harm to make it pretty.

The judge took the bench. Names. Rights. Counsel. Then, metronome-voiced, the clerk asked my mother to stand and state her plea.

“Guilty,” she said. It sounded like a word learned in a foreign language class: close enough to pass, far from music.

“Do you admit you made a false report against your granddaughter knowing it false?” the judge asked.

My mother’s eyes slid and came back. “Yes.”

“And that you placed a necklace in her bag intending security to find it and believe she’d stolen it?”

She swallowed. “Yes.”

“Do you wish to say anything to your granddaughter, who is present, about the harm you caused?”

I watched the fight in her throat—decades of throwing darts and calling it instruction. Then, maybe because her lawyer nudged her away from the cliff with a look, she said, “I’m sorry.”

No one clapped. Grace doesn’t make noise you can hear.

My father stood next. He tried to make a speech. The judge cut him off with judicial politeness so sharp it almost bled. “Sir, answer the question.”

“Yes,” he said at last. “I lied.” He turned toward Emma—he never could resist an audience—and attempted a human smile. “I’m sorry.”

Emma didn’t nod. She didn’t play forgiving or outraged. She breathed, shoulders up-down, up-down, the way Ms. Flores taught: oxygen is a plan.

Sentencing: fines, service, a course with an earnest acronym—RELATE: Restorative Empathy, Listening, Accountability, Truth-telling, Engagement—probation, a suspended count hung like weather, and an order: any contact with Emma only at her written invitation. The judge recommended counseling for “intergenerational boundary repair.” I wondered what therapist wanted to frame that certificate. Then I remembered it wasn’t my problem. The law had drawn a line and handed me the pen.

Reporters waited in the hall. No shouting. A camera blinked red without lunging. Pastor James stood near the fountain not looking like an apology courier. People who’d never said hello at the grocery store said hello. No one spoke to my parents. That’s its own cruelty. I didn’t celebrate it. I didn’t mourn it. I noted it, because noting builds memory you can use later, not to hurt yourself, but to remember you can live through gavels and quiet after.

Allison from the paper lifted her notebook an inch. I shook my head. She tucked it away. Chapter closed.

“Pancakes?” Emma asked, voice small, reasonable.

“Always,” I said.

Booth five was open. Saint Whiskers didn’t appear. The waitress brought coffee and said nothing, which was perfect. On our way out, a man in a suit picked a program out of a puddle and shook it like force could chase water away. People are funny about what they think they can wring dry.

When we got home, a thin notice waited: Evidence Release—Item #7841 (Gold Necklace). To be retained until completion of probation. Upon release, claimants to petition for possession. The word claimants made me laugh hard enough to sit down. I taped the card to the fridge under the cow, next to BEGIN.

“Which one are we?” Emma asked, wary of the word like it might bite.

“We’re the ones who turn it into something else,” I said.

“Good,” she said.

That night, she wrote her six-weeks letter and tucked it in her music folder. I didn’t read it, because therapy is a country where parents don’t need passports. I watched her shoulders loosen. I poured two waters and sat across from her. We did nothing urgent and everything important.

Six weeks can be a lifetime. The market went back to tomatoes. The prayer chain returned to bunions and biopsies. At school, Emma took first chair again and no one wrote a think piece about it. That was my favorite part: the ordinary quiet of a life no longer audited by strangers.

The day the release matured from paper to calendar, Powell called. “Judge Levin’s chambers, two o’clock,” she said. “Not a fight. A formality with a pulse.”

“Who gets it?” I asked, though I knew.

“The court directs release to the custodial parent of the victim,” she said. “You. For safekeeping until she’s eighteen or she instructs you otherwise in writing. The order notes ‘expressed intent to transform object to prevent future harm.’ The statute didn’t have a box for that. We drew one.”

The envelope was small, evidence tape crossed neat. The pendant didn’t radiate heat like a coal the way my memory insisted. It lay there dumb as metal. That’s the thing about heirlooms: they steal power from the mouths that talk about them. Silence them and you get what you had all along. Gold.

We didn’t take it home. We took it to Winthrop. Maya had the mat laid out. “I’m sorry for what it was,” she said. “Let’s see what it is.”

I slid the pendant onto felt. Without my mother’s throat behind it, the scalloped rim looked less like a crown and more like a gear that never fit. The scratch on the clasp shone like a familiar lie.

“I don’t want it around my neck,” Emma said. “I don’t want to see it in photos.”

“Can we melt it?” I asked.

“Yes,” Maya said. She called into the back: “Theo?”

Theo emerged wearing loupes, rouge streaked on an apron. He had hands that trust fire and eyes that had seen what people attach to metal. He didn’t ask for the story. He didn’t need it. He set the crucible and lit the torch. The flame opened with a hiss like truth.

“Remember,” he said as the gold blushed and sagged, “we’re not destroying value. We’re changing shape.”

The disc pooled. The chain went liquid. Theo poured the molten gold into a clean ingot mold. He handed Emma a hammer. “Your strike,” he said, “so the metal remembers who listens to who now.”

She glanced at me. I nodded. She brought the hammer down—not theatrically, not like a movie—just enough. A new sound entered the room.

“Beautiful,” Theo said. He cut a sliver, rolled it into a ribbon, curved it around a mandrel, fused, filed, sanded, polished. Inside the finished ring he stamped one word: BEGIN. The rest of the bar he let cool and weighed: twenty-two grams of future.

“For you?” he asked me, tapping the bar.

“A donation,” I said, surprising myself with how quickly the answer stood up. “The shelter’s building a safe room. They can auction it, melt it again, turn it into door hardware. Something that locks for the right reasons.”

Theo nodded. “Best fate.”

Maya wrapped the leftover in tissue and wrote BEGIN AGAIN on the label in square letters. We left lighter by a necklace and heavier by choices.

At home, I replaced the green card with a photocopy of Judge Levin’s order and a photo of Emma’s hand wearing the ring. Ms. Flores told her to mark milestones: court date, first day back, first full night of sleep, first time a stranger said nothing. We added this.

My sister brought basil and gossip she’d filtered for harm. “They’re picking trash on Route Four,” she said. “Court-ordered. Dad wears gloves like the litter has opinions. Mom wears a visor.”

“Good,” I said, then softened it because I am trying not to become what I fight. “Fine.”

“Tell me they clean the median,” Emma said.

“Both sides,” my sister deadpanned. “Justice is symmetrical.”

We laughed longer than the joke deserved, the laughter of people who let something rot inside them see the air.

Spring recital arrived with squeaky chairs and pastel programs. Copland filled the gym in that earnest way American music has, making bad acoustics sound like a barn with doors flung to fields. Emma lifted her bow for a short solo. The gym settled around it. She wasn’t playing to fix anybody’s reputation. She was playing because she practiced and she could. People clapped like they were clapping for notes and fingers and the idea that a kid can go through a bad winter and still make a clean sound.

By the punch bowl, Pastor James lingered at the edge of my sight line, hands in pockets, doing what good pastors do when they don’t want to be mistaken for cops. “Permission to say congratulations and vanish?” he asked.

“Granted,” I said.

He nodded at the ring. “Nice,” he said—not loaded, not a sermon. Just a word the size of itself.

On the way out we passed the trophy case: state titles that meant everything and nothing, a deflated basketball signed by a boy the town said was going places until he didn’t like where he landed, the orchestra photo from three years ago with Emma in the second row, bow too long. She looked and didn’t flinch. “They should dust this,” she said.

“I’ll put it on the PTA list,” I said.

“Paper,” she said, bumping my shoulder.

My mother sent one more letter. Narrow blue lines. Return the necklace. No please, no question mark. I scanned it to Maria and Powell with the subject line For the file; do not attempt transplant, then fed it to the grill. Ash curled differently every time.

I didn’t block my mother’s number. I didn’t need to. Silence had grown bones. The restraining order stood like a fence we didn’t have to point at. The court drew it. We live inside it.

My father tried the back door once—metaphorically. He sent my sister to report they were “considering leaving town until people remember who we are.” I didn’t ask where. The country is full of neighborhoods that will sell you a new story if you can afford the HOA. If they went, fine. If they stayed, fine. The ring didn’t care. Neither did Judge Levin’s order.

Summer arrived damp and inevitable. Emma shelved books at the library with a surgeon’s focus and the posture of someone finished being a surface for other people’s opinions. Our coffee table turned into a camp trunk of paperbacks. We built rituals: diner pancakes in booth five when a day was too loud; loops around the empty winter lake house when my sister needed to breathe; Saint Whiskers sightings like folklore. (She is real. She is large. She is immune to your theology.)

At the shelter fundraiser, the auctioneer held up the gold bar and said, “This came from a family that decided heirlooms should be useful.” Hands went up. A woman from a construction company bought it—“Door hardware,” she told me after, as if she’d been in the jeweler’s back room. When the safe room opened, the handles gleamed a quiet color and felt solid under the palm. The plaque by the door didn’t list donors; it listed verbs: Shelter. Lock. Rest. Begin.

Emma’s six-week letter turned into twelve, then into a list she no longer needed to tape to anything. Tiny things I can do without thinking about them: make dumplings without tearing the wrappers; jog two miles; say no without an apology; tune by ear even when the gym clock is loud; tell a boy to stop; take a bow like it’s nothing special and everything. She showed me a page. I slid it into a folder. Paper again—this time compost.

On the last day of summer we went back to the diner because endings need pancakes as much as beginnings. Booth five was open. The waitress set a plate of blueberries on our table like a secret. “On the house,” she said. “You two put on a good show this year.”

“We didn’t do anything,” Emma said, delighted. “We just kept showing up.”

“That’s the show,” the waitress said.

A new sign hung near the Saint Whiskers notice: PLEASE DO NOT TAP ON THE GLASS. THE FERAL CAT IS NOT ENTERTAINMENT. Someone had drawn a little heart and a ring next to it. I didn’t take a picture. Some things you carry without proof.

In September, a thin letter arrived: Probation completed. Case closed. Inside, one line from Judge Levin: The law has finished speaking. You can stop listening to it now.

I took the ring to Theo and asked him to cut the tiniest shaving from the inside and solder in the last sliver we’d kept from the BEGIN AGAIN bar, the part we saved for no reason that becomes a reason later.

“Insurance,” I said.

“Memory,” he said. He stamped a second word inside, smaller, almost an echo: AGAIN.

When Emma got home, she held the ring under the kitchen light and squinted at the tiny new word. “What if I lose it?” she asked.

“Then we’ll begin again without it,” I said. “It’s not the magic. You are.”

She slid it back on. It looked the same to everyone not looking—which was the point.

I won’t tell you my parents transformed. They didn’t. People whose religion is control rarely convert. They adjusted to their smaller audience. My mother shops out of town. My father reads legal notices to the last line. They found a church that likes persecution stories with the villain left vague. Maybe that’s their beginning. It isn’t mine.

Here’s mine: I don’t attend their tragedies. I don’t assign them my weather. On holidays, I cook too much and my sister’s kids spill soda and the dog steals rolls and Emma plays something not seasonally appropriate because she can. The door hardware at the shelter warms under a thousand hands. When Emma takes her ring off to knead bread, it leaves a pale indentation; her skin remembers without needing to see. She’ll grow up and go to a college that cares more about essays than about threats signed Consider the family; she’ll have bad days; she’ll have a life so ordinary it feels like a miracle.

Sometimes on Sundays we drive past the church lot and wave at no one. Then we sit in booth five and watch people be people. Saint Whiskers saunters down the alley, tail punctuating the air. The waitress tops my coffee and asks if we want blueberries. I say yes. Emma says yes. We eat them like communion, tart and sweet.

“Do you think it’s over?” she asked once, weeks after the case closed, when life stopped dividing itself into Before and After and started calling itself Tuesday again.

“For us,” I said. “Yes.”

“And for them?”

“That’s not an interesting question anymore,” I said, and we laughed the particular laugh of women who have put down a weight no one else saw and decided not to pick it up for company.

On the fridge the cow magnet holds grocery lists and party invitations. The green card lives in a file with passports and the deed and the smoke alarm manual. Paper did its work. Fire did the rest. Metal did what it’s best at: remembered heat and became useful.

If you ask me about the heirloom now, I’ll tell you the truth. It isn’t a ring or a bar or even a court order. It’s this: the ordinary afternoon when my daughter puts her elbows on my kitchen table and asks for pancakes for dinner and I say yes without needing anyone’s approval. It’s Copland in a gym with bad acoustics. It’s the feel of a handle that locks from the inside and releases when you want it to. It’s a cat in an alley that doesn’t need feeding to remain a legend. It’s a word stamped so small inside a ring you can forget it’s there and still live by it.

Begin. Again.

News

My daughter was being booked for shoplifting. I just stared at the screen, watching the security footage, and a terrible truth sank in: It was my mother who had just stolen her innocence.

The bench outside juvenile intake wasn’t made for adults. It was the kind of narrow, varnished plank you’d find in…

They found the gold necklace in my daughter’s bag and took her away. What no one realized was that the necklace wasn’t just a piece of jewelry—it was the key to a family secret that would send my own mother to prison.

The bench outside juvenile intake wasn’t made for adults. It was the kind of narrow, varnished plank you’d find in…

My own mother framed my daughter for shoplifting a gold necklace. She had no idea that her act of cruelty was the very thing that would expose a lie she’d been living for thirty years.

The bench outside juvenile intake wasn’t made for adults. It was the kind of narrow, varnished plank you’d find in…

He called me “garbage.” I didn’t get angry. I just quietly walked out, pulled out my phone, and with a few taps, made sure he would never insult anyone with that much power again.

“Garbage” at Dinner — and the Deal That Died The Harrington estate’s dining hall gleamed like a temple of…

He thought I was just a young girl who didn’t understand business. It wasn’t until he saw my name on the deal’s cancellation notice that he finally understood he had just signed his own demise.

“Garbage” at Dinner — and the Deal That Died The Harrington estate’s dining hall gleamed like a temple of…

“The young girl is garbage,” he sneered at his son. He didn’t know that I was the anonymous CEO he was trying to impress, and his multi-billion dollar deal was about to fall through.

“Garbage” at Dinner — and the Deal That Died The Harrington estate’s dining hall gleamed like a temple of…

End of content

No more pages to load