Mom tilted her chin and smiled that thin, blade-bright smile. “You’ll never be as good as your sister.”

It was supposed to be a toast—her 60th birthday, family gathered around the table with good china and worse intentions. Sarah’s engagement ring threw little shards of light across the linen. My father had made osso buco; the kitchen smelled like orange peel and thyme. And still, somehow, the night devolved to this one familiar sentence, burnished by years of use, handed to me again like heirloom silver.

I stood. My napkin slid onto my chair.

“Then ask her to pay your bills.”

For the first time in twenty years, the room obeyed me. Knives stopped. Wine paused mid-pour. Even the wall clock seemed to hold its breath. Sarah’s eyes widened. My father’s fork hit his plate with a small insistent sound. Across from me, my mother’s mouth opened and closed around nothing. Truth, finally given air, expanded to fill the space where all the unspoken things had been living.

I am Daniela, thirty-two, the younger sister with paint under her nails. My home movies are full of me trying to hang my artwork on the fridge while Chopin swells from the piano in the other room—Sarah, five years older, the family’s thesis statement. At seven, I held up a painting of our family and watched my mother squint at the proportions. “Skies are blue, not purple, Daniela.” At thirteen, I brought home a report card with solid B’s and a couple of A’s, and she hummed an absent “That’s nice,” before turning back to whatever university packet Sarah’s future had requested that week.

My father, an engineer with the gentle patience of a man who has drawn the same line straight a thousand times, was a counterweight. He bought me sketchbooks when he brought Sarah new metronomes. He pinned my drawings at his office. At night, when the house was full of scales and practice schedules, he’d sit on the edge of my bed and say, “Not all stars are the North Star, Dany. Some are nebulae—you have to look a little closer to see what they’re doing, but when you do, they’re spectacular.”

I clung to that. Through middle school’s fractions that refused to divide cleanly and high school’s first boy who didn’t ask what my sister was doing next year before asking me out. Through the fashion design competition I won my sophomore year and the way my mother turned my trophy in her hands like it was a trinket of adolescence gone too long. “If you used half this energy on your algebra, you’d be Sarah,” she said, not unkindly, but not kindly either. It was simply the water we swam in: Sarah and Not-Sarah.

If you grow up there, you learn strategies. You learn to redirect conversations and recognize the subtle shoulder adjustments that mean your contribution will be noted and moved around, like a vase you brought into a room that someone else is decorating. You learn to leave the house early and return late. You learn that art can be both refuge and rebellion.

I went to state university’s design program with a partial scholarship and a seat-of-the-pants budget, calluses on my fingers from sewing and working retail. My mother, who could recite Sarah’s LSAT score in her sleep, scanned the acceptance letter and said, “Well. It’s better than nothing.”

I learned a lot about nothing those years. That nothing stretches deliciously when you’re alone in a studio at 1 a.m. draping fabric on a dress form while a friend reads you poetry from a nearby stool. That nothing tastes like coffee bought with tips between classes. That nothing can be a clear glass space you fill with your own ideas.

I learned something about yes, too. Yes felt like Professor Carter—the former designer with the scarlet lipstick—turning my sketchbook around in her hands and saying, “There’s a point of view here. Raw. Don’t let anyone sand it down.” Yes felt like seeing my name typed small but present on a list of emerging designers selected for a group show. Yes, loudest of all, felt like a theater director saying into a microphone, “The costumes were characters tonight. Daniela Williams created something special.”

I called home, jittery with it. “New York Fashion Week,” I told my mother. “Emerging designers showcase. One piece, but Mom, it’s—”

She breathed into the wrong part of the phone. “Is that the main one or a side thing? Don’t get your hopes up too high, Daniela. These creative fields are… competitive. Not everyone has natural talent like your sister.”

By then I had learned to make two separate lists in my head. One held the words that mattered. The other contained the words you put in a drawer, close, and walk away from.

The night of her birthday, the table was crowded—my father’s careful cooking, my mother’s careful makeup, Sarah’s careful life. When she announced her promotion—youngest partner—the relatives clapped like the room was wired to do it. When she announced her pregnancy, my mother actually cried. “My first grandchild,” she said, and kissed Sarah’s knuckles with reverence.

When the noise subsided, I tried my news in the space there. “One of my designs was selected for New York Fashion Week,” I said. “Emerging designers platform. It’s a big deal in the industry.”

“Is that so,” my mother said, the way you might say you heard rain was expected. “Any exposure is good exposure.”

Then she talked about venue rentals for their fortieth anniversary and asked Sarah, immediately, if she’d contribute.

That was the tinder. The spark came when I offered what I could—design work, custom invitations, the kind of things I’ve watched people pay a fortune for—and my mother tilted her head and said, gently as a hammer, “I meant financially, Daniela. As usual.”

“As usual.” Two decades compressed into two words.

Then she said the sentence that has sat as a furniture piece in every room of my life. “You’ll never be as good as your sister.”

The room watched me stand up. The room watched me set down my napkin and finally set down something heavier.

“Then ask her to pay your bills.”

The rest wasn’t a speech, not really. It was years. I said I loved Sarah, which was true. I said I was happy for Sarah, which was truer now that it wasn’t being used to bludgeon me. I said that if my mother needed a measuring stick she could take it to the person she’d been measuring me against and stop putting it across my shoulders like a yoke. I said I had tried to meet her where she lived, and I was done moving my furniture into a house where everything would be rearranged while I was sleeping.

My father said “Elizabeth” the way you address a person when you’d like them to stop being a concept. “You pushed Sarah to excel and pushed Daniela to be Sarah. That’s not the same thing.”

Sarah stood slowly and came to my side. “It’s true, Mom.” She had the grace to look my way. “And I never told you what it felt like being the yardstick.” She took a breath. “I was jealous of her,” she said then, almost laughing at it. “She always knew what she wanted. I have been performing competence so long I forgot to ask if it was mine.”

My mother, who organizes the world in columns, sat between two lists she had made and did not recognize who had written them. “I just… wanted the best for you,” she said, but the sentence could not carry itself, not in the face of all the ways she had chosen what looked best over what was good.

I went outside and met the night air like a person coming up from underwater. The stars were ridiculous with indifference. I thought of my father’s old line about nebulae.

What comes after the line you draw is messy. It isn’t always applause and it isn’t always a slammed door. In our case, it was a week of silence and then a text from Sarah—“Coffee? Just us?”—and three hours in a café where we managed to be sisters without looking at a third person to see if we were doing it correctly. It was my father showing up at my studio, touching a pinned muslin like it was a map. “Explain this seam to me,” he said, and when I did, he nodded like you nod at a bridge.

It was a text from my mother the night before Fashion Week. Good luck tomorrow. I know this is important to you. Small, but miraculous in its very restraint. It was seeing her at the reception afterwards, out of place and rigid but there, and, best of all, wearing the vintage silk scarf I found and had cleaned and gave her for her birthday, and hearing her attempt language in a dialect she has never spoken. “It’s very… creative,” she said. “The audience seemed quite… impressed.”

It was teaching myself to accept a compliment without changing it into something else. “Thank you for coming,” I said. “It means a lot.” It was watching her hand hover and then orient itself correctly around mine.

The work began to resemble the future I’d dreamed alone at 1 a.m. in college. An avant-garde designer with a conscience brought me onto her team, and I learned how to make ideas fast enough to meet deadlines without sanding off their edges. A year later I signed a lease on a studio with bad lighting and good bones, and two part-time assistants who flung open windows while they argued about music. Industry blogs used my full name in sentences that contained the words “innovative” and “sustainable.” Buyers learned that when I said a jacket would transform on stage, it did.

I didn’t stop missing a thing that never existed, but missing and needing are not the same muscle. I learned to maintain boundaries with my mother like they were part of the architecture. I learned to say “No, Mom,” without making myself small to do it. I learned to hear old patterns and not inhabit them. She did not metamorphose into a different person; she learned to ask questions about my work that weren’t rhetorical. She framed one of my sketches and hung it near Sarah’s diploma. It looked, to me, like an acknowledgement that walls can hold more than one thing.

Sarah and I found a rhythm. I made her baby a christening gown that included lace from our grandmother’s tablecloth. She sent me articles about women who invented their own careers and didn’t choke on the word “proud” when she used it in my direction.

I was standing at my first solo exhibition a year later when my mother stopped in front of a piece I’d made from a dismantled man’s suit and a fluted pink silk dress from the 1940s and said, softly, to the air, “I wore something like that when your father and I first started dating.” I led her to the next piece—a re-imagining of that dress with architectural seaming—and told her it was hers if she wanted it. She touched the fabric like a person petting a shy animal. “You made this for me?” she said, and when I nodded she looked like she might break in a way that made me fear and hope both.

“You have such talent, Daniela. Such vision,” she said. “I’m sorry it took me so long to see it.”

What she offered wasn’t absolution—it was an attempt. I took it. Not because I needed it to be whole, but because my hands were free now that they weren’t trying to catch comparisons falling from the ceiling.

“What’s the courage made of?” someone asked me after reading a piece about the show. I wanted to say milk from mornings you made your own breakfast and took your own bus. I wanted to say pencil shavings. I wanted to say one sentence said right in a room built for a different conversation.

It was smaller than that and bigger. It was deciding that your worth is not a derivative equation where someone else’s excellence is the independent variable. It was standing up at a table you set and saying, finally, “I’m full,” when all your life you have been asked to make room for a second helping of someone else’s hunger.

When my mother sneered, “You’ll never be as good as your sister,” I heard, perhaps for the first time, the part of the sentence that mattered. As good. Good for whom? Good to whom? Good by whose definition?

I don’t know that my mother will ever learn to see nebulae without someone pointing. But I have learned to be one without asking permission.

And yes, she pays her own bills now. Sometimes she asks Sarah for advice and sometimes she asks me about archives and sometimes she asks my father to roast lamb because no one does it quite like him. He does, whistling, and hands me the carving knife. “Straight lines,” he says, and watches me draw them.

News

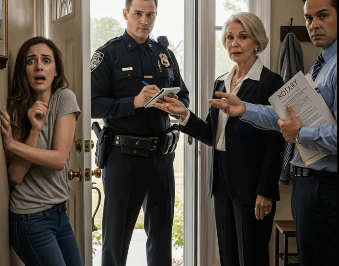

After the wedding, my daughter-in-law came to my door with a notary and said, “we sold this house, you’re going to a nursing home.” i replied, “perfect — but first, let’s stop by the police station. they’re very interested in what i sent them about you.”

Amanda stood in my living room, her smile as cold as December frost, while the notary shuffled papers like he…

I bought a house without telling my parents — then discovered they had copied my key, showed up while i was at work, and even brought a locksmith when it no longer fit.

The paper grocery bag slipped from my fingers before I could fully process what I was seeing. The jar of…

At our annual family gathering, my 6-year-old asked to play by the lake with her cousin. I hesitated, but my parents insisted. Minutes later, I heard a splash—she was in the water while the cousins laughed. I pulled her out, and she cried, “She pushed me.” When I confronted my sister, my mother defended her granddaughter and even slapped me. I stayed silent, but when my husband arrived, he made sure no one escaped accountability.

My name is Sarah, and this is the story of how one terrible day at a picturesque family lake house…

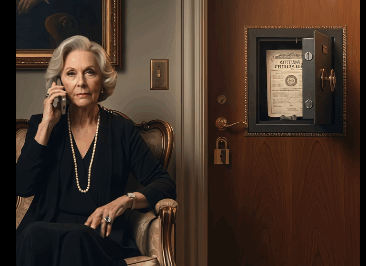

My daughter-in-law locked me in a room in my own mansion, telling everyone I was “confused.” She didn’t know the deed proving I owned the entire estate was hidden in that very room. As she hosted a lavish party downstairs, I called my lawyer. “Serve the eviction notice now,” I said. “Let’s give her guests a real show.”

When my son married Vanessa, she gradually convinced him I was becoming confused and relegated me to the guest wing…

On my wedding day, my husband pushed me into the pool—but my father’s reaction stunned everyone.

It was a Tuesday night, three weeks before the wedding, when my future was laid out for me on the…

I demanded my wife give her $7,000 maternity savings to my sister. She refused, and I accused her of being selfish. Then she broke down and handed me an envelope. “It’s not for our future baby,” she cried. Inside was the …

When I first asked my wife to give up the $7,000 she had saved for her maternity expenses, I never…

End of content

No more pages to load