The Boy Who Would Not Leave

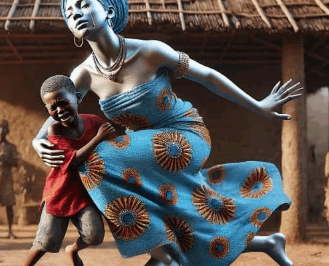

Darab was eight the night his world turned to stone.

He was small—big dark eyes, thin limbs that looked too fragile to hold his small body upright. He lived in a mud hut on the edge of a quiet village with his mother and father. His father had taken a second wife, Lami, and the household never recovered the balance it had lost. Lami watched Darab and his mother with a thorny jealousy; she had a way of turning small things into blows.

That evening Darab’s mother was stirring a thin pot of soup—precious in a house that sometimes ate only once. The aroma made Darab’s stomach squirm with hope. “Just wait a little,” she promised, smiling despite the smallness of their meal. He believed her the way small children believe miracles.

Then Lami came in and, without a word, kicked the pot into the embers. The soup hissed and vanished into the coals; the pot rolled and clanged away. Darab’s mother cried out. Lami laughed, loud and sharp. “Why should she cook in my kitchen?” she spat. “Let her and her son see what they will eat tonight.”

Hunger cramped Darab’s spine; tears pricked his eyes. That night the house burst into argument. The father returned late from the market to find his wife weeping and an empty pot. He called Lami out. Words flared. Lami, furious and ungovernable, came back with a knife. In the scuffle she cut his hand; blood spewed and the quarrel turned violent.

In panic, Darab’s mother fled. She ran straight into the night, ignoring the village taboo that bound everyone from seeing certain rituals. She had only taken three steps before the native doctor—Baba Ekon—appeared, red and white chalk smeared on his skin, smoke curling from his staff. He was chanting as he walked the path where the villagers had forbidden sight.

He saw her and screamed, “You have broken the sacred law!”

Before she could beg, her legs froze, her throat stiff. Her arms lifted as if to run and then stopped midair. Her face went as gray as river stone. At home, Darab and his father heard the cry and rushed out. Where the woman had been stood only a statue: grey, mouth half-open, hands frozen as if mid-gesture. The moonlight sheeted over her stone face. She no longer moved.

Darab threw himself at the statue and pounded it. “Mama, please wake up,” he begged, rubbing the cold foot as though warmth might return. The statue did not answer. Lami came out and laughed, triumphant. People gathered at dawn, whispering away from the stone woman as if her gaze could fix them the way it had fixed her.

From that night on Darab’s life split along two lines: the boy who would not leave his mother’s feet, and the household that kept going with the hollow where a wife had been. Darab slept beside the statue and rubbed its dusty legs clean with a small cloth. When hunger thinned him, an old neighbor, Mama Nenna, brought rice and soup. Auntie Kem, a sister of his father who lived in the city, treated him tenderly when she visited, but even her kindness couldn’t replace his small, stubborn ritual of being near the stone mother.

Months passed. Darab grew paler, smaller; the village’s pity and gossip dulled into a background hum. His father, who loved his son though he had once failed his wife, watched the boy and felt his heart break a little more each day. He tried rituals and charms—salt sprinklings, palm oil libations, midnight prayers—but the stone wouldn’t budge. Each failed remedy cost him a goat or a sack of yams. A father can give everything but time; the man had none to spare.

Finally, with an ache that pulled at his ribs, Darab’s father decided to send him to the city to live with Auntie Kem. “She will feed you and teach you,” he said. “She will keep you safe.” Darab pressed his forehead to the statue’s cool toe and whispered, “I will come back for you,” then let his father lift him away.

Auntie Kem’s house was a different world: cushions, a small television, steady meals. She wrapped him in clean clothes and combed his hair until it shone. She took him to school where teachers tried to coax him into laughter. Slowly, with patience and warm hands, Darab learned to sleep without pressing his face to stone. He began to grin in small bursts, like someone at the edge of a new shore.

And then, one day, on a dust-scented street near the market, Darab saw a black SUV slide past a fruit stand. A woman stepped out—wrapped in bright cloth and gold—and for a breath he saw his mother. The world narrowed; everything else blurred. The woman’s profile, the curve of her cheek, the softness of her mouth—some deep chord in him recognized it.

He ran, shouts scattering apples and startled vendors, and threw himself against her back. She startled, then stiffened, and the driver gently pulled him away. “Who are you?” she demanded. Her voice had no warmth. “Let me go.”

“Mother,” Darab sobbed. “It’s me. I’m Darab.”

She stepped back as if burned, and the SUV swallowed her away. People watched, murmuring. The woman had not called for him. She had not once looked at him as if she knew him. Darab stood on the dusty road and watched the taillights fade, and something inside him cracked.

Auntie Kem believed him, though she feared what his grief might be doing to his mind. She vowed to find the woman. They tracked the SUV to a gated compound and knocked at the gate. A guard peered down and then called the woman. When she stepped onto the balcony, Auntie Kem recognized the face that had haunted Darab—shock made her knees weak.

Inside the compound, the woman listened as the father told the story—how a wife had turned to stone, how a son waited by the statue. The woman sat as the words tumbled. Then she rose, brought out an old photograph, and looked at it as if it contained a past that ached to be known: two young women in gowns, their arms around each other like twins.

“Her name?” the woman asked softly. When the father said the name, she folded like paper and wept.

It was then they learned the truth. The woman was not the missing wife but her twin sister—long separated by family rifts and a marriage that had driven her abroad. She had returned to the country, unaware of the small village story. She had seen a boy who looked like him and—ashamed, frightened, or perhaps bound by old family wounds—she had turned away. She wept not because she had turned her back on a son but because the family mines of blame and silence were far deeper than anyone had told her.

When the woman finally knelt and told Darab in a voice that trembled with recognition and sorrow, “I am your mother’s twin. I am your aunt, but I will be your mother too,” something wide and soft unrolled inside his chest. She lifted him and pressed her cheek to his. He knew the arms, the voice, the stories that fit a heart like a memory.

Back in the village the statue remained. People whispered that perhaps it was the woman’s twin—by her love and grief—who had shaken the air and loosened a single tear of morning dew from the stone. Whatever the reason, Darab’s father no longer knelt there alone. He had sent his son away to save him, and now—years of worry and ritual later—the boy returned with a new life stitched around him.

Auntie Kem’s prayers and Baba Ekon’s rituals and the father’s steadfast work had not been wasted. The boy who once pressed his forehead to a stone and whispered for his mother came to the compound to find a woman who claimed him and a family who, finally, refused to let him vanish. She named herself openly the sister who had gone away; she told Darab stories of a woman who loved him, then explained the stumbling reasons she had not known earlier: letters that never arrived, a family that would not forgive a marriage abroad, names erased and histories bent by shame.

Darab’s smile returned in slow, startling pieces. He learned the shape of a new room and the steady rhythm of cooked meals. He played with boys in the street in a way that did not end with his face on a stone step. He went to school and his teacher stopped calling Auntie Kem worriedly. People whispered less.

At Christmas they visited the village together. Darab walked hand-in-hand with the woman who now called herself his aunt-mother. He placed flowers at the statue’s base and stepped back. Not all things return. Some losses remain hard and raw—even if the heart has been mended enough to carry forward. The stone woman looked as she had: still and silent. The village still told the story of taboo and the cost of breaking it. But Darab no longer sat there every day. He sat there sometimes—rubbing the statue’s cool toes with the same small cloth—but not out of hunger and despair. He sat from a place of memory and respect. He told the statue how school had gone and what songs he’d learned. He pressed his cheek against the stone and felt, not the hollow of abandonment, but the round warmth of a life that had kept going.

What saved him, in the end, was not a single miracle but the slow accumulation of mercies: an aunt who made a home, a father who repented in his way, villagers who softened with time, and a woman who—once she understood—claimed him as family. Darab learned that not all absences are final and not all returns look like the ones children’s stories promise. Families can be broken and rearranged; sometimes the pieces fit in unexpected ways.

Years later, when children asked Darab the story of the statue, he would tell them about the night he thought stone had taken everything. He would tell them about the woman who came in a black car and frightened him, and about the sister who knelt and called herself an aunt and then a mother. He would tell them how small kindnesses—Mama Nenna’s warm soup, Auntie Kem’s steady hands, Baba Ekon’s rites and even the father’s stubborn love—had saved him.

He would end the story by shrugging a little and smiling the soft smile of people who had lived through something hard and found, not an ending, but a way forward.

“Sometimes,” he would say, “the heart has to be given again before it can heal. And sometimes, the family we need is the one we choose to keep.”

News

She turned to a statue overnight, and he had to find her. The search ended in the city park, where he had to figure out how to turn her back, or just sit with her forever.

The Boy Who Would Not Leave Darab was eight the night his world turned to stone. He was small—big dark…

He found her in the city, but she was a statue. As he stared at her, he realized she was just one of many, and his search had just begun.

The Boy Who Would Not Leave Darab was eight the night his world turned to stone. He was small—big dark…

He woke up to find his mother had turned to stone. He spent the day in a frantic search, only to find her face staring back at him from a public sculpture in the city square.

The Boy Who Would Not Leave Darab was eight the night his world turned to stone. He was small—big dark…

His Mother Turned Into A Statue Before He Woke Up, And he Found Her In The City

The Boy Who Would Not Leave Darab was eight the night his world turned to stone. He was small—big dark…

I stayed silent eight years ago. This Thanksgiving, when my sister showed up screaming on my lawn, she had no idea that my silence wasn’t a sign of weakness—it was a promise of what was about to happen.

My adopted sister threw my science trophy at my head, screaming, “You don’t deserve this,” and poisoned my food for…

The trophy, the poisoning, the screaming on the lawn—eight years later, it was the same toxic cycle. My family thought I was back in the same trap, but I was about to show them that this Thanksgiving was the last one they would ever spend with me.

My adopted sister threw my science trophy at my head, screaming, “You don’t deserve this,” and poisoned my food for…

End of content

No more pages to load