Chapter 1: The Coldest Day

The wind that swept down the avenues of Boston’s Back Bay was a living thing. It had teeth, and it bit relentlessly at the small, shivering form of four-year-old Eliza.

She was impossibly small for her age, a bundle of sharp angles wrapped in a coat so thin it was more a suggestion of warmth than a provider of it. The wool was matted, the color long since surrendered to a dull, urban gray, and the sleeves stopped a full two inches above her chapped wrists. In her left hand, clutched with a grip that belied her size, was a single daisy. It had been a cheerful yellow when she’d plucked it from a crack in the pavement two days ago, but the frost had already claimed it. Now, its petals were brown and limp, a mirror of the cold sorrow that clung to the air.

Eliza didn’t understand death. She only understood “gone.”

“Mommy’s gone to be a star, sweet pea,” Anna, her mother, had whispered just last week, her voice a dry rattle from deep within her chest. They had been huddled in their “nest” — a recessed doorway of a closed-down bookstore, shielded from the wind by a fortress of sodden cardboard.

Eliza had looked up at the sliver of sky, polluted and starless. “Which one?”

Anna had coughed, a terrible, racking sound that seemed to tear her apart from the inside. She’d pulled Eliza closer, her own body radiating a frantic, unnatural heat. “The brightest one. The one that winks just for you.”

Three days later, the heat was gone. Anna’s skin was the color of the sidewalk, and her eyes, which had always held the last embers of a dying fire, were dull. Eliza had shaken her, crying “Mommy, wake up, I’m cold,” until a man in a blue uniform had gently pulled her away.

Now, she was here. She had followed the whispers. The men at the shelter, the nice lady who gave her a stale donut, they had all been talking. “The Harringtons.” “The funeral.” “Trinity Church.”

Eliza knew the Harringtons. They were the monsters in her mother’s bedtime stories. “They live in a house made of ice, sweet pea,” Anna would say, her voice laced with a bitterness Eliza didn’t understand. “And their hearts are just as cold. Stay away from them.”

But Mommy was in the church. They’d taken her. Eliza had seen the long black car and the shiny wooden box. She had to see Mommy. She had to give her the flower.

Trinity Church was not a house of God; it was a fortress of wealth. Carved stone angels wept over arched doorways, and stained-glass windows, dark from the outside, promised a jewel-toned warmth within. A line of gleaming black cars—Mercedes, Bentleys, and Cadillacs—were parked along the curb, disgorging a river of black-clad mourners. They were a different species from the people Eliza knew. The women were wrapped in thick fur coats that shimmered in the weak winter light, their faces hidden behind veils and sunglasses. The men wore coats of dark wool, their shoes polished to a mirror shine, their faces grim and important.

They flowed past Eliza as if she were invisible, a piece of urban debris no more significant than the trash can on the corner. Their expensive perfumes mingled with the scent of car exhaust, a stark contrast to the smell of damp wool and unwashed skin that clung to Eliza.

She clutched her daisy and slipped between a man clutching a briefcase and a woman dabbing at dry eyes with a silk handkerchief. She made it to the massive oak doors, pushed open just enough to admit the flow of guests.

The warmth that hit her was a physical shock. It was thick with the scent of lilies—so many lilies—and old, polished wood. Organ music, low and somber, vibrated in her chest. For a moment, she was just a four-year-old girl, mesmerized by the light. The inside of the church was a cavern of gold and deep red. A thousand pinpricks of light came from candles lining the aisle, leading to the front where the shiny wooden box rested, buried under a mountain of white roses.

“Mommy,” she whispered, her voice lost in the soaring music.

She took one step onto the plush red carpet, then another. She just wanted to get to the front. She just wanted to put her flower on the box.

“And just what do you think you’re doing?”

The voice was not loud, but it cut through the music like a shard of glass. It was cold, metallic, and heavy with disdain.

Eliza froze. She turned, looking up. And up.

The woman standing before her was as tall and unyielding as a marble statue. She was impeccably dressed in a black Chanel suit, a rope of pearls at her throat the only break in the darkness. Her silver hair was coiled into a perfect, tight chignon, and her face, though etched with the fine lines of age, was sharp and predatory. Her eyes, a pale, icy blue, raked over Eliza, taking in the matted hair, the dirt-smudged face, the threadbare coat.

This was Matilda Harrington. The matriarch. The woman her mother had called “The Ice Queen.” She did not look sad. She looked inconvenienced. Annoyed. Disgusted.

Eliza had never seen her before, but she knew, with the primal instinct of a small animal, that this was the source of her mother’s fear.

“Mommy,” Eliza tried again, pointing with her free hand toward the casket. “I came to see Mommy.”

Matilda’s upper lip, thin and painted a discreet nude, curled in a sneer. She didn’t recognize her own granddaughter. She saw only an intrusion, a stain on the perfect, curated sorrow of the day. She didn’t know that this child’s eyes were the exact, almond-shaped green of the daughter she was about to bury.

“Anna?” Matilda let out a short, sharp laugh that was more a bark. “You knew Anna? I’m not surprised. She always did surround herself with… refuse.”

She looked past Eliza, her eyes scanning the vestibule. She spotted a large man in a dark suit standing by the door, an earpiece curling into his ear. He was private security, hired to keep the press out. Or, as it turned to be, the grandchildren.

Matilda raised a single, manicured finger and beckoned him over. The man, broad as a refrigerator, was at her side in an instant.

“Mrs. Harrington?”

“Daniel,” she said, her voice dropping to a low, venomous hiss. She didn’t even look at Eliza as she spoke, keeping her gaze fixed on the altar, as if the child’s presence was too offensive to bear. “Remove this… filth. Now.”

The word hung in the warm, lily-scented air. Filth.

Eliza flinched, her hand tightening on the daisy. She didn’t know what the word meant, but she knew how it felt. It felt like the cold sidewalk. It felt like the empty ache in her stomach.

The security guard, Daniel, hesitated. His gaze flickered from the imperious old woman to the terrified child. He was a father. He had a little girl at home, just a bit older than this one, who was currently warm in her bed, safe from all this. He could see the terror in Eliza’s eyes, the desperate plea. But he also saw the woman who signed his paycheck.

“Ma’am, she’s just a child…” he began, his voice a low rumble.

“She is trash,” Matilda snapped, her patience gone. “She is street trash, trying to disrupt my daughter’s funeral. Do I need to call your superior, or will you do the job you were hired for?”

Daniel’s face hardened. He looked down at Eliza, his expression unreadable. He had his orders.

Eliza backed up a step, her small body trembling. “No… please… I just want to give Mommy…”

But it was too late. The guard’s large, calloused hands, surprisingly gentle, wrapped around her tiny torso. He lifted her as easily as a sack of flour. Her legs kicked, and the wilted daisy, her last connection to her mother, fell from her grasp and was immediately crushed under the guard’s heavy boot on the red carpet.

A small, animal sound of despair ripped from Eliza’s throat. “No! My flower! Mommy!”

The guard didn’t say a word. He turned, his face a mask of professional duty, and carried the crying, struggling child back toward the heavy oak doors. The elite funeral-goers, the senators, the bank presidents, the old-money families of Boston, watched the scene with mild, detached curiosity. They saw a disturbance, a brief, unpleasant interruption, quickly and efficiently handled. They turned back to their hushed conversations, adjusting their furs and checking their watches.

The cold air hit Eliza again as the doors opened. The guard, Daniel, carried her past the threshold, down the stone steps, and all the way to the tall, imposing iron gates that separated the churchyard from the sidewalk.

With a heavy, metallic groan, he opened the gate just wide enough to step through, and then he deposited Eliza on the freezing sidewalk.

“I’m sorry, kid,” he mumbled, his voice thick with an emotion Eliza was too young to identify as shame.

He didn’t look back. He shut the gate. The latch clicked, a final, definitive sound of exclusion.

Eliza was on the outside. The warmth, the music, the light, and her mother, were all on the inside.

She scrambled to her feet, her small hands, now blue with cold, gripping the iron bars. She pressed her face against the cold metal, her tears beginning to freeze on her cheeks. “Mommy!” she screamed, her voice thin and reedy against the wail of the wind. “MOMMY! Don’t leave me!”

Inside, the organ music swelled, a triumphant, somber chord that swallowed her cries whole. The funeral-goers took their seats in the polished pews. No one looked back. No one saw the small girl clinging to the gates, sobbing for a mother who could no longer hear her.

Chapter 2: The Iron Gates

The cold was a predator. It seeped through the soles of her worn sneakers, numbed her fingers until they were stiff and useless, and stole the breath from her lungs. Eliza’s cries had faded into ragged, hiccupping sobs. Her body had gone from trembling to a state of rigid, energy-saving stillness. She was too cold to cry anymore.

She just watched.

Through the iron bars, she had a clear, heartbreaking view. She saw the heavy doors of the church swing shut, sealing away the last of the warmth. The world was reduced to this: the unforgiving iron against her cheek, the gray sky above, and the indifferent sounds of the city—a distant siren, the rumble of a bus, the hiss of tires on the wet pavement.

A few passersby hurried past, collars turned up, eyes down. They saw her, but they didn’t see her. She was just another sad, ignorable part of the city’s landscape. A problem for someone else to solve.

Eliza’s world had shrunk to the space of a single, agonizing thought: Mommy is in there, and I am out here.

The guard, Daniel, was back at his post by the door, a stoic statue. He kept his back to the gate, a deliberate act of willed ignorance. He couldn’t do his job and look at her at the same time. He’d heard the click of the gate, and the small, desperate sobs that followed. He’d have to live with that sound. He justified it to himself: he had a family to feed. Mrs. Harrington’s checks were always on time. But the shame settled in his stomach like a block of ice.

Inside, the funeral was proceeding with choreographed precision. The organist finished the prelude, and a minister with a voice like smoothed gravel began to speak. “We are gathered here today to mourn the tragic, untimely passing of Anna Harrington…”

Matilda sat in the front pew, her spine ramrod straight. She was the very picture of grieving, aristocratic stoicism. A man next to her, a cousin from the New York branch of the family, leaned in. “Terrible business with that child at the door. Who was it?”

Matilda’s gaze remained fixed on the flower-draped casket. “No one,” she said, her voice a frozen whisper. “Just a beggar. The city is full of them.”

Outside, Eliza’s hands finally lost their grip. Her fingers, too numb to hold on, slipped from the bars. She slid down to the sidewalk, huddling into a small, miserable ball at the base of the gate. She drew her knees to her chest, trying to conserve the last bitof her body’s fading warmth. She was so tired. The cold was making her sleepy. Maybe, she thought, her mind growing fuzzy, if I go to sleep, I can be a star with Mommy.

It was this image—a small, four-year-old child curled up and accepting a frozen defeat on the sidewalk—that greeted Mr. Alistair.

A black Lincoln Town Car, older but impeccably maintained, pulled up to the curb. It was not flashy like the other cars; it was a vehicle of quiet, established purpose. The back door opened, and a man emerged, moving with the slow, deliberate stiffness of old age.

Mr. Alistair Finch was in his late seventies, a man from an era that valued discretion and honor above all else. He was the last of his kind. He wore a heavy wool overcoat, a hat, and spectacles with thick lenses that magnified his eyes, making them look perpetually startled. But they weren’t startled; they were sharp. They had seen everything.

Alistair had been the Harrington family lawyer for forty-five years. He had drafted the prenups, managed the trusts, and, most painfully, processed the paperwork when Matilda had formally, cruelly disowned her only daughter, Anna.

He was late, and he hated being late. He’d been at his office, retrieving one very specific, very important document from the safe.

He adjusted his spectacles and looked toward the church, his face grim. He was here out of a deep, abiding duty to the one person he had failed: Anna.

He was the only one she had kept in contact with. She would call, once or twice a year, from a payphone. She’d never asked for money—her pride wouldn’t allow it. She’d only asked him to “keep an eye on things,” to “make sure the dragon doesn’t burn the whole world down.” And she had talked about her daughter.

“She’s a light, Alistair,” Anna’s voice had been, thin and crackling over the line. “She’s so smart. She’s… she’s everything they weren’t.”

Alistair’s gaze fell from the church spires to the gate. He stopped. He saw the bundle of rags. He saw the small, pale face. He saw the matted, tangled brown hair.

His breath caught in his chest. He had never met the child, had only seen one blurry, dog-eared photo that Anna had sent him. But he knew. He knew instantly.

“Oh, my dear God,” he whispered, his voice shaking.

He hurried over, his gait as fast as his old legs would allow. He knelt on the cold sidewalk, the damp immediately soaking through the knee of his expensive trousers. He didn’t care.

“Eliza?” he said, his voice softer than she’d heard all day.

Eliza’s head snapped up. Her eyes, dazed and clouded with cold, tried to focus. She saw a kind face, wrinkled like an old apple, and eyes that were looking at her, not through her.

“Are you Eliza?” Alistair asked again, his heart breaking. He could see Anna’s eyes staring back at him. Matilda’s cruelty was one thing; her blindness was another.

Eliza just shivered.

Alistair acted quickly. He shrugged off his own heavy overcoat—a coat that cost more than Eliza and Anna had earned in a lifetime—and wrapped it around her. It swallowed her whole, a cocoon of warm wool and the scent of lavender soap. He scooped her up. She weighed almost nothing.

“You’re safe now, child,” he murmured, his voice thick with a sudden, righteous anger he hadn’t felt in decades. He held her against his chest, her small, cold face tucked into his neck. He could feel the faint, rapid thrum of her heart.

He looked at the gate, at the church beyond. He looked at the guard, Daniel, who was now staring at them, his face pale with dawning, horrified realization.

“She… she’s with you?” Daniel stammered, taking a step toward the gate.

“She is,” Alistair said, his voice like granite. “And you, sir, are a coward.” He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to. The quiet condemnation was more powerful than any shout.

Daniel flinched as if struck.

“Open this gate,” Alistair commanded.

“But… Mrs. Harrington’s orders… no one is to…”

“I am Alistair Finch, Mrs. Harrington’s legal counsel,” Alistair said, cutting him off. “And this,” he said, adjusting Eliza in his arms, “is Eliza, Anna’s daughter. And if you do not open this gate right now, I will personally see to it that you are not only fired, but that you face charges for child endangerment. Am I clear?”

The color drained from Daniel’s face. He fumbled for his keys, his hands shaking. He unlocked the gate and pulled it open, his eyes wide with terror—not of Alistair, but of what was to come.

Alistair strode past him without a second glance. “You are supposed to be in there,” he whispered to Eliza, so only she could hear, “more than any of them.”

He walked up the stone steps, the small child hidden within the folds of his massive coat. He reached the oak doors and didn’t pause. He pushed them open with his shoulder and stepped inside.

The warmth, the scent of lilies, the low thrum of the minister’s voice—it all washed over them.

“And so, we commend Anna’s spirit to the Lord, a spirit taken too soon, a spirit of…”

The minister’s voice faltered. He had looked up from his notes and seen the old lawyer, standing at the back of the church like an avenging angel, holding a bundle of rags.

Every head in the church turned. The sea of black parted, conversations died, and a profound, shocked silence fell.

Matilda Harrington, in the front row, turned her head, her face etched with annoyance at the interruption. Her eyes met Alistair’s.

Alistair looked right back at her, his gaze unwavering. He did not care about the senators, or the bankers, or the socialites. He cared only for the small, shivering weight in his arms and the promise he had made to a dead woman.

He took a step forward, his shoes clicking on the stone floor.

Then another.

He began the long, slow walk down the center aisle, straight toward the casket, straight toward the woman who had just thrown her own blood out into the cold. And with every step, the tension in the church grew from a shocked whisper to a suffocating, unbearable weight. The real funeral was about to begin.

Chapter 3: The Interruption

The only sound in the cavernous church was the rhythmic click… click… click of Alistair Finch’s hard-soled shoes on the marble aisle. Each step was a gavel strike, an indictment.

He walked with the unhurried, implacable pace of a man who knows he is right. In his arms, Eliza, enveloped in the impossible warmth of his coat, slowly uncurled. She peeked out, her small face framed by the dark, expensive wool. Her eyes, wide and green, took in the scene. She saw the rows of shocked faces, the high-arched ceiling, the ocean of candles. And at the front, she saw the shiny box, now so close.

The minister, a man accustomed to the polite, predictable grief of the wealthy, was utterly lost. He stood at the pulpit, his mouth slightly open, his prepared remarks forgotten.

In the front pew, Matilda Harrington’s face had gone from annoyance to a pale, controlled fury. How dare he? How dare Alistair, her paid servant, her employee, create such a spectacle? And to bring… that… in here.

Alistair did not stop when he reached the front pew. He didn’t even look at Matilda. He walked right past her, past the casket, and stopped directly in front of the pulpit, forcing the minister to take a step back.

He turned, not to the minister, but to the congregation. He was now the one addressing the crowd. Eliza, still in his arms, was held up for all to see, a tiny, ragged accusation.

“Mr. Finch,” Matilda hissed from the front row, her voice a low, dangerous vibration. “This is a funeral. You are creating a scene. Remove yourself, and that child, at once.”

Alistair looked down at her. His magnified eyes, usually so kind, were now burning with a cold fire.

“Matilda,” he said, his voice, aided by the church’s perfect acoustics, carrying to every corner. It was the first time in forty-five years he had used her first name in public without the prefix “Mrs.”

The entire church gasped as one.

“I am not the one creating a scene,” Alistair continued, his voice steady. “I am the one correcting one. The scene,” his voice rose, “was a four-year-old child, thrown onto the sidewalk in the freezing cold.”

“That child is a vagrant!” a man in the second row—a Harrington cousin—called out, emboldened by Matilda’s glare.

“That child,” Alistair said, turning to the man, “is Eliza. Anna’s daughter.”

Another wave of shock. This was not a ripple; it was a tidal wave. Whispers erupted. Anna’s daughter? That’s not possible. I thought Anna was… Good Lord, look at her… she has Anna’s eyes.

Matilda’s face, for the first time, cracked. Not with grief, but with the sudden, horrifying realization of a tactical error. She had not known Anna had a child. Or, perhaps, she had known and had chosen to forget, to erase.

“You’re lying,” Matilda spat, rising to her feet. The mask of the grieving mother was gone, replaced by the snarl of the cornered matriarch. “You are a senile old fool. Anna was a drug-addicted, homeless… she was incapable of caring for anything. This is a trick. A pathetic attempt to… what? Steal a part of the inheritance?”

Alistair actually smiled, a thin, sad, terrible smile. “My mental faculties, Matilda, are perfectly intact. As is my conscience. Which is more than I can say for you.”

He reached inside his breast pocket, the one not pressed against Eliza’s small body. He retrieved two items. First, a worn, folded piece of paper. A birth certificate.

“Eliza Marie, born four years ago. Mother: Anna Harrington. Father: unknown.”

He placed it on the pulpit.

“And second,” he said, producing a long, cream-colored envelope, sealed with wax. “The reason I was late.”

He turned to the minister. “I believe this supersedes your eulogy. It is, in fact, the only eulogy that matters.”

“What is that?” Matilda demanded, taking a step toward the pulpit.

“This,” Alistair said, holding it up, “is the last will and testament of your daughter, Anna Harrington. Signed and notarized by me, six months ago. She gave it to me for safekeeping, ‘for when the time came,’ as she put it.”

The church was utterly, tomb-like silent. The only sound was Eliza’s quiet breathing, a small puff of white mist in the cold air that had followed them in.

“This is absurd,” Matilda said, though her voice now held a tremor of uncertainty. “Anna had nothing. She was disowned. She has no say here. She has no inheritance to give.”

“That,” Alistair said, his eyes gleaming behind his thick lenses, “is where you are tragically mistaken.”

He carefully handed Eliza to the stunned minister. “Hold her. Please.” The minister, on autopilot, accepted the child, who was warm and sleepy.

Alistair put on his reading glasses. He broke the wax seal. He unfolded the document.

“I, Anna Harrington, being of sound mind and body…” he began, his voice booming with legal authority. He skipped past the preamble, the legal boilerplate. He knew exactly where the relevant clause was.

“Ah, here we are. Section 3, subsection A: The Harrington Trust. As my parents are well aware, the trust fund established by my grandfather, Thomas Harrington, is inviolate. It could not be touched by them, nor could my access to it be legally revoked upon my death, only deferred.”

Matilda’s face went white. She knew this. It had been a source of decades of frustration. Her father had distrusted her, and had locked up Anna’s inheritance (a sum that, after thirty years of compound interest, was now valued at over fifty million dollars) until Anna’s death, at which point it was to be absorbed back into the main Harrington estate… unless Anna had a direct heir.

“I bequeath the entirety of the Thomas Harrington Trust,” Alistair read, his voice ringing with triumph, “to my beloved, precious daughter, Eliza.”

The room spun. Fifty million dollars. To that. To the filth.

Matilda lunged forward. “She has to be twenty-one! The bylaws! It’s in the bylaws!”

“I’m so glad you brought that up, Matilda,” Alistair said, not looking up from the page. “Anna was, as I’m sure you’ll recall, a very intelligent woman. She knew you. She knew you better than anyone.”

He read the next part, slowly, savoring every word.

“My full inheritance is to pass to my daughter, Eliza. However, I am aware of my family’s… sensibilities. I am aware of their capacity for cruelty, and their obsession with appearances. Therefore, I add one binding, non-negotiable stipulation. This stipulation must be met, in full, before this will can be executed and the trust transferred.”

He paused, looking over his glasses directly at Matilda. The church held its breath.

“My daughter, Eliza, must be present at my funeral. Not as a spectator. Not as a guest. She must be treated, by my mother, Matilda Harrington, as the chief mourner and the sole guest of honor. She must be seated in the front row, in her mother’s rightful place. She must be treated with the dignity and respect that I was never afforded.”

He looked up. The silence was absolute.

“And,” Alistair’s voice dropped, “in the event this stipulation is not met? In the event my daughter is turned away, or hidden, or disrespected in any way?”

He let the question hang.

Matilda was trembling, her hands clenched into claws at her side. She understood. The other guests understood. They were all witnesses.

Alistair looked down at the paper. “In such an event, the will is to be declared void, and the entirety of the fifty-million-dollar trust is to be immediately and irrevocably donated to a series of charities. Specifically,” he cleared his throat, “the Boston Shelter for the Unhoused, The Children’s Defense Fund, and a small, private foundation Anna has established… for disowned children.”

The trap was sprung. It was beautiful. It was perfect. Anna, from beyond the grave, had crafted the perfect, inescapable prison for her mother.

If Matilda acknowledged Eliza, she would lose control of the fifty million dollars. It would go to the “filth.”

But if she denied Eliza, which she had already done, and which Alistair and everyone else had now witnessed… she would lose the fifty million dollars anyway. It would go to the very people she despised.

It was a choice between public humiliation and financial ruin… or… public humiliation and financial ruin. The only variable was who got the money.

Matilda’s eyes darted from Alistair, to the casket, to the child, and to the faces of her peers. She was trapped. She was, in this moment, completely and totally defeated by the daughter she had dismissed as a failure.

Alistair folded the paper. “So, Matilda. You have a choice. Do we call the security guard back, to testify that he was ordered to ‘remove this filth’ from the premises? Or… do you welcome your granddaughter, the guest of honor?”

Chapter 4: The Last Will

The silence in Trinity Church was no longer one of mere shock; it was a heavy, suffocating blanket of judgment. Every eye was on Matilda Harrington. The whispers had ceased. The air was thick with the unsaid, the realization that they were witnessing not just a funeral, but the public dismantling of a dynasty.

Matilda stood frozen, her face a mask of warring impulses. Rage, disbelief, and a cold, calculating financial panic warred behind her eyes. Fifty million dollars. It wasn’t just the money; it was the control. It was the power. And her daughter, her weak, pathetic, failed daughter, had outmaneuvered her from a homeless shelter.

She looked at Alistair, her eyes burning with a hatred so pure it was almost visible. He simply looked back, his expression patient, holding all the cards.

She looked at the congregation—at the Gables, the Winthrops, the Cabots—all the old-money families of Boston, their faces rapt with the most delicious, salacious society scandal in a generation. They would be dining out on this for years.

And finally, she looked at Eliza. The child was still being held by the bewildered minister, her small, smudged face peering out from the folds of Alistair’s coat. She was no longer just “filth.” She was the fifty-million-dollar question.

Matilda was a pragmatist. She had been defeated, but she could still control the narrative. Or, at least, she could perform the act required to keep the money within the family, even if it was in the hands of this… creature. To let it go to charity was unthinkable. It was a loss. Matilda Harrington never, ever lost.

Her spine, which had been bent in a moment of fury, snapped back to its ramrod-straight position. The mask of the grieving matriarch slipped back into place, but it was different now. It was the mask of a woman performing a distasteful but necessary duty.

She gave Alistair a curt, sharp nod. The single, smallest possible gesture of concession.

Alistair nodded back, as if he had expected nothing less. “A wise decision.”

He turned to the minister. “May I have the child, please?”

He took Eliza back into his arms. He then walked the few steps to the front pew and looked down at Matilda. He didn’t say a word. He just waited.

The humiliation was a physical thing. Matilda Harrington, who had never knelt for anyone, was being forced to grovel. She understood her part in this play. Anna had written it for her.

With a look of profound, soul-deep revulsion, Matilda stepped forward. She looked at Eliza, her lip curling. “Come here,” she said. The words were clipped, sharp.

“No,” Alistair said softly.

Matilda’s head snapped up. “What?”

“That is not how one treats a guest of honor,” Alistair said, his voice quiet but firm. “Anna’s stipulation was clear. ‘Dignity and respect.’”

He was going to make her play the part in full.

Matilda’s hands clenched. The pearls at her throat seemed to tighten. She closed her eyes for a brief second, drawing on a lifetime of social discipline. When she opened them, the rage was gone, replaced by a cold, false sweetness that was somehow more terrifying.

“Of course,” she said, her voice a strained, sugary facsimile of kindness. She held out her arms. “Eliza. What a… lovely name. Come to… Grandma.”

Eliza, who had felt safe for the first time all day in Alistair’s arms, recoiled. She buried her face in Alistair’s neck.

Alistair gently pried her away. “It’s all right, child,” he whispered. “You must. But I will be right here. I will not leave you.”

He placed Eliza on her feet. The child stood for a moment, wobbling on the plush carpet, a tiny, ragged island in a sea of wealth.

Matilda stared at the dirt on Eliza’s face, the grime on her coat. She took a silk handkerchief from her purse. With a visible, shuddering effort, she bent down—an act that seemed to cause her physical pain—and roughly, briskly, scrubbed at Eliza’s face.

“Mustn’t be dirty,” she muttered, her words for her. It was not a gesture of love. It was a gesture of sanitation.

She cleaned the child’s face, then straightened her pathetic, thin coat. She then took Eliza’s small, chapped hand in her own gloved one. The contrast was stark: the smooth, black kidskin and the small, raw, red hand.

Matilda led her granddaughter to the front pew. She did not look at her. She stared straight ahead at the casket. She sat down, pulling Eliza down beside her.

Eliza was seated in the front row. The stipulation was met.

The entire church exhaled.

Alistair Finch watched this, his heart a heavy stone of grief and triumph. He had won. Anna had won. But at what cost? He looked at the small child, now dwarfed by the massive, carved-oak pew, her tiny sneakers not even reaching the floor, and knew the fight was just beginning.

He turned back to the pulpit, clearing his throat. The minister, grateful, scurried back to his seat.

“There is one final item,” Alistair said, his voice thick with emotion. He pulled a second, smaller, and far more worn envelope from his pocket. This one was not sealed with wax. It was a simple, creased letter.

“This was also in Anna’s effects. It is not part of the will. It is… a letter. It is addressed to Eliza.”

Matilda stiffened. “She can’t read. Give it to me.”

“No,” Alistair said, his voice gentle but absolute. “I will not. Anna asked me to read it. She said, ‘Read it so the whole world can hear.’”

He opened the letter. The handwriting was faint, shaky, but unmistakably Anna’s.

“My Dearest, Sweet Pea,” he began, his voice cracking for the first time.

“If you are hearing this, it means Mommy is a star now. Don’t be sad. I am not cold anymore. I am not in pain. And I am shining so, so brightly for you.

“I am so sorry I left you. I fought. I fought so hard to stay with you. You were the one good, true, perfect thing in my whole life. You were my light.

“You are going to hear many things about me. They will say I was weak. They will say I was a failure. They might be right. But they will never say I didn’t love you. I loved you more than the sky.

“You are in a house full of ice. I know. It’s so cold there. But I want you to remember something, Eliza. You are not one of them. You are not cold. You are not ice. You are fire and sunshine. You are the daisy that grows in the crack of the sidewalk. You are stronger than all of them, because you know how to love.

“There is a man there. His name is Mr. Alistair. He is the only one who was kind. Trust him. He will keep you safe.

“And my… mother,” Alistair’s voice faltered on the word, “if she is there. I want her to listen. I forgive you. Not for what you did to me. But for what you did to yourself. You chose that ice. You chose to be cold. And you will die cold. But my daughter… my daughter will be warm. I have made sure of it.”

Alistair was openly weeping now, as were several people in the congregation. He wiped his spectacles.

“Be brave, my Eliza. Be kind. And live. Just live. That will be my perfect revenge. I will be watching, my sweet pea. I will be the brightest star.

“All my love, forever, Mommy.”

Alistair folded the letter. The church was silent, save for the sound of quiet sobbing.

He looked at the front pew. Matilda Harrington was rigid, her face white, her eyes fixed on the casket. A single, hot tear, a tear of pure, unadulterated rage and humiliation, carved a track through her expensive makeup.

Alistair walked down from the pulpit. He sat in the pew directly behind Matilda and Eliza. He put his hand on Eliza’s small shoulder. She looked back at him, her green eyes full of questions.

He gave her a small, watery smile. “It’s all right, child,” he whispered. “We’re going to be all right.”

Eliza turned back to the front. She looked at the shiny wooden box, now covered in roses. She looked at the woman beside her, this cold, stiff “Grandma.” And then she looked up, toward the high, stained-glass windows, as if searching the sky.

The minister, finally finding his voice, stood. “Let us… let us pray.”

But the funeral was over. The old order had died, and a new one, small and scared but holding the power of fifty million dollars and a mother’s love, was sitting in the front row.

News

Black maid mistakenly stole money and kicked out of billionaire’s house — But what hidden camera reveals leaves everyone speechless…

Black maid mistakenly stole money and kicked out of billionaire’s house — But what hidden camera reveals leaves everyone speechless……

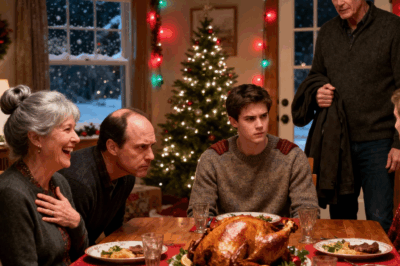

At Christmas Dinner, My Grand Ma Laughed & Said, “Good Thing Your Parents Pay Off Your Student Loans.” I Replied, “What Loans? I Dropped Out To Work Two Jobs.” Dad Said, “It’S Not What You Think.” Then Grandma Stood Up … And Said Something That Changed The Family Forever

The House of Shadows At Christmas dinner, my grandma laughed and said, “Good thing your parents pay off your student…

I Was a Billionaire Tech Mogul Crumbling in First Class While My Starving Son Screamed for the Mother He’d Just Lost in a Tragic Accident, Until a Stranger with Worn-Out Shoes and a Heart of Gold Did the Unthinkable—An Act of Primal Intimacy That Silenced the Entire Plane, Humiliated My Wealth, and Saved My Soul at 30,000 Feet.

PART 1: THE SCREAMING SILENCE OF WEALTH The sound wasn’t just a cry; it was a siren. It was a…

BREAKING: Jon Bon Jovi CANCELS ALL 2026 NEW YORK SHOWS — “Sorry NYC… I don’t sing for values that have lost their way.

Jon Bon Jovi — one of the city’s most enduring rock icons and a lifelong supporter of its working-class soul…

BREAKING: Dolly Parton Sparks National Debate After Declaring She Would Boycott the Super Bowl

Dolly Parton Sparks National Debate After Declaring She Would Boycott the Super Bowl A Bold Statement from a Country Legend…

ch2-“GOODBYE, MY DEAREST FRIEND…”: Linda Robson Breaks Down in Tears as She Says a Final Farewell to Pauline Quirke, the Woman Who Shared Her Laughter, Her Secrets…and Her Life.k

In a moment that has broken hearts across the nation, Linda Robson — actress, presenter, and lifelong friend — was seen in…

End of content

No more pages to load