“This is my lazy, fat daughter.”

The words rang through the ballroom like a bell tolling at a funeral. My father said them with a smirk that curled the edges of his lips—the kind of smile he’d worn all my life whenever he found a new way to diminish me. Guests laughed, the tinkling, polite kind of laughter that people use when they want to fit in, even if it’s cruel. I felt their eyes on me, hot and mocking, and for a moment the floor seemed to tilt beneath my shoes.

Then it happened. Four young men in matching tuxedos, groomsmen standing near the head table, exchanged a glance. One of them, his voice steady, said, “Sir.” The other three finished the sentence together. “She’s our commanding officer.”

The sound carried over the laughter, sharp as a trumpet note in the still air. The room froze. My father choked mid-sip, his wine spraying from his mouth onto the crisp white tablecloth. He coughed, sputtered, his face going pale as the realization set in that the daughter he had mocked in front of 200 wedding guests was the same woman these men stood ready to salute.

That was the moment the whole wedding turned upside down.

I had always known this day would test me. Weddings are supposed to be joyful, but for me, it was a battlefield of a different kind. My only son, Mark, was marrying into the Hastings family, a well-to-do clan with deep roots in Virginia and a reputation for wealth that seemed to stretch back to the Civil War. The reception was held in their country club, a sprawling estate where chandeliers dripped with crystal and the waiters glided silently with silver trays. It was a stage set for judgment.

I chose my dress carefully: navy blue, simple, understated, a strand of pearls from my late mother around my neck. My life had taught me that blending in was safer than drawing attention, especially in front of my father. At 72, he had only grown sharper with his tongue, more cutting with his jokes. He lived for moments when the spotlight landed on him, even if it came at someone else’s expense, and too often that someone was me.

From the time I was a teenager, he’d called me names—”big girl,” “useless,” “slow.” I learned early to keep my head down, to survive by becoming invisible in my own family. My brothers, thinner and louder, earned his approval. I carried the weight of his disappointment the way I carried the medals on my uniform: quietly, without asking for recognition.

What my father never knew was that invisibility had its advantages. I joined the army at 19. He thought it was a phase, that I’d wash out before the first deployment. Instead, I found myself. Discipline was my language. Resilience, my armor. Years of his ridicule had built a core of steel in me. I rose through the ranks, serving in Iraq, then Afghanistan, and later at bases across the states. My soldiers knew me as Major Carter, then Lieutenant Colonel Carter. By the time of my son’s wedding, I wore the silver eagle of a full Colonel.

But my father never asked, and I never told. Maybe some part of me wanted to keep it hidden. If he couldn’t be proud of me, then I’d stop giving him the chance to reject me. So I showed up to family dinners in plain clothes, never mentioning the ribbons, the deployments, the command. To him, I was just the daughter who never measured up, the family embarrassment he tolerated out of obligation.

And then came the wedding.

Mark had been dating Jennifer Hastings for just over a year. She was bright, ambitious, a corporate lawyer who carried herself with the polish of someone born into money. Her family welcomed my son warmly, though I could see the appraising looks they gave me, weighing my dress, my jewelry, my small-town accent. It was the same look my father had given me all my life.

During the reception, when Jennifer brought her parents over to meet me, I braced myself. Her mother’s smile was tight, her father’s handshake cool, but nothing prepared me for my own father stepping forward, puffing up his chest as though he owned the moment, and saying the words that still burned in my ears: “This is my lazy, fat daughter.”

The crowd laughed. Not all of them, but enough. And that was the cruelest part. Laughter is contagious. People don’t always mean it, but they go along because silence feels like complicity. I stood there, heat rising in my cheeks, my heart pounding. Part of me wanted to run. Another part wanted to lash out, to shout the truth. But I didn’t need to. My soldiers did it for me.

The groomsmen had served under my command in Afghanistan. I hadn’t known they would be there. Mark had made friends with them after moving back home, never realizing they were *my* men. They’d kept the connection quiet out of respect. But when they heard my father’s words, they decided enough was enough.

“Sir, she’s our commanding officer.”

The phrase dropped like a hammer, breaking the moment wide open. The laughter died instantly. Guests turned to stare at the men, then at me. My father sputtered, red-faced, wine dripping down his chin. And in that silence, for the first time in decades, I felt the weight shift. I wasn’t the one exposed anymore. He was.

I didn’t smile. I didn’t gloat. I simply stood still, letting the truth hang in the air. My soldiers looked at me, not with pity, but with the respect they had always shown—respect my father had never given. The orchestra faltered and fell silent. You could hear the clink of a glass being set down somewhere in the back. The Hastings family looked stunned, their polite superiority unraveling before my eyes. And my son, dear Mark, looked at me as if he was seeing me for the first time.

It wasn’t just the end of a cruel joke. It was the beginning of a reckoning.

***

People think humiliation happens all at once, in a loud room with witnesses. But most humiliation is patient. It trains you. It teaches you to take up less space, inch by inch, until you are a whisper in your own life.

I grew up on a two-lane road outside of Chillicothe, Ohio, where the neighbors knew the mileage of every truck and the price of every bale of hay. My father ran a small plumbing and HVAC outfit out of a cinder block shop behind our house. His work shirts always smelled like copper and furnace dust. He was good with systems and bad with people, especially the people under his roof. If a pipe leaked, he tightened it. If a child hurt, he mocked it. That was his method: tighten, mock, move on.

By fifth grade, I was “Big Em.” I wasn’t the biggest kid in town, but I was big enough for the jokes to land. My mother tried to intercept them with casseroles and kindness, the way women of her generation patched everything with food and apologies. She loved me out loud, and he cut me down in public, and those two forces canceled each other out until I felt like zero.

On Sundays, we sat on a polished pew under a stained-glass window of wheat and water. The preacher spoke about grace, and afterward, my father would shake his hand and tell him he’d done a fine job. Then, in the parking lot, he would squeeze my upper arm like he was checking a melon and say, “We’re laying off the donuts this week, right?” The men laughed like it was just locker room ribbing. The women looked away. Humiliation loves a parking lot.

I learned early that invisibility was safety. If I could not be pretty, I could be useful. I stacked parts in Dad’s shop, swept the floor, balanced the checkbook on a yellow legal pad. He relied on my neatness while ridiculing my body. “You’d be perfect if you came with a shut-off valve,” he told me once in front of a supplier. I pretended not to hear. I always pretended.

In high school, I ran cross-country in an oversized T-shirt. My times were average, but I liked the private victory of a steady pace—no applause, just breath and grit. A guidance counselor slid a brochure for the army across her desk during senior year. “You’re organized and stubborn,” she said. “Those go far in the service.”

My father laughed when I brought it up at dinner. “You’ll quit the first time a drill sergeant yells,” he said, chewing with his mouth open. “You can’t even handle a hill run.” My mother pressed her napkin to her lips and said nothing. In our house, silence was always the safest answer. I signed the enlistment papers on my lunch break and hid the carbon copies in my geometry binder.

The day I shipped out, my father stood with his thumbs in his belt loops like a foreman of the world. “Try not to embarrass us,” he said. I lifted my duffel and didn’t look back. On the bus, I watched the farms blur into factories and then the factories into a base with metal beds and shouted schedules. I decided to become very good at doing as I was told. Boot camp liked neatness and stubbornness. So did the army.

The cadence in my head changed from my father’s voice to a drill sergeant’s bark, and somehow that felt like mercy. The sergeant didn’t know my history or my body. He only cared whether my boots were shined, my bunk was tight, and my time on the course beat yesterday’s. I could work with that. Work is a refuge when your worth has always been contested.

Deployment came two years later. Iraq first—heat that made your skin feel stapled on, sand that found its way into letters from home. Then Afghanistan—mountains that punished you, and men who would follow you if you proved you could count on yourself. I learned a thousand small reliabilities: how to read a map by red light; how to listen to a private without making him feel inspected; how to say “we go together” in a dozen different tones until it was true.

I wrote home in neutral sentences. “I’m well. The crew is fine. The sunsets are prettier than you’d think.” When I earned my first commendation, I didn’t mention it. When my mother mailed me a clipping about my brother getting a new boat, I wrote back, “Tell him I’m proud.” It was easier to keep the ledger of our family balanced by not entering my own numbers.

Promotions arrived the way dawn does: gradual, then obvious. I pinned on Captain and then Major. I learned to keep a straight face when a private called me “sir” by accident. In rooms full of men, I spoke low and precise, and the words carried farther than volume. There is a kind of authority that doesn’t have to be announced. It simply refuses to be miscounted.

When my mother’s heart failed, I flew home in my Class A’s because there was no time to change. At the funeral, the pews were the same, and the wheat and water still poured colored light across the aisle. Women I’d known since childhood squeezed my hands and said, “Your mama bragged on you something fierce.” My father shook the preacher’s hand and said, “She was a good woman,” like he was commenting on a furnace that had finally given up. On the church steps, a neighbor asked about my uniform. “Just office work,” my father said before I could answer. “She files papers and tries not to break a sweat.” I took the dish of macaroni someone handed me and went inside.

After that, I stopped bringing uniforms home. I showed up in jeans and soft cardigans that made me look like an elementary school secretary. My father had always wanted me smaller. I obliged in the only dimension I could control: visibility. The less he knew, the less he could use. When a ribbon appeared on my rack for something I didn’t care to relive, I pushed it to the back of the closet and told myself that heroism didn’t require an audience.

Years later, I took command of a battalion, and the weight of it felt right in my hands, like a wrench you’ve used all your life. My soldiers were a quilt of America: farm kids, first-generation college grads, a baker from Baton Rouge who could break down a radio blindfolded, a kid from Queens who recited psalms before patrols. They didn’t need me thin. They needed me steady. In that steadiness, I found a dignity I could stand inside.

Meanwhile, my father’s shop mottled with rust and success in equal parts. He bragged about my brother’s promotions and sent me photos of their new trucks. At Christmas, he carved the ham while listing his own aches like medals: “Knee, shoulder, dignity. You should try losing some weight,” he told me between helpings. “It’s not healthy.” I wanted to tell him about the rucks I’d carried, the miles, the nights I’d measured fear out in spoons and still did the job. Instead, I passed the rolls and asked for the salt. I learned somewhere along the line that winning with him meant refusing to play.

When Mark was born, my father smiled at a newborn the way he had never smiled at me. I didn’t hold it against him. Infants are safe from comparison. As my son grew, I practiced a new language: praise that wasn’t conditional, boundaries that weren’t barbed. When his father left, I carried the weight of two jobs and made our home tidy, because tidiness is a kind of mercy when life is loud. Mark learned to tighten a faucet and to make his bed on the same day. I told him that strength isn’t loud and power isn’t cruel, and when he brought home report cards, I put them on the fridge without turning them into a scorecard for his soul.

Somewhere in the middle of deployments and school pickups, I made a quiet promise to myself: I would stop auditioning for a part I had already played and lost—my father’s favorite. Favor is weather. Respect is climate. I couldn’t control the weather inside him, but I could build a climate inside me that wouldn’t change with his forecast.

Years of silence passed this way—disciplined, chosen, sometimes lonely, always safer than the alternative. I wore my rank in the places it mattered, and hung it on a hook by the door when I came home. In the little town where people counted other people’s portions, I learned to count my own breaths and call it enough.

And then Mark fell in love, and a wedding invitation arrived like an inspection notice from the universe. Family gathers around milestones the way dust gathers in corners you haven’t looked at in a while. I knew what that ballroom would test. I didn’t expect it to break. But I was done needing my father to measure me. I had my own tape.

***

The Hastings Country Club had the kind of parking lot where the cars all looked like they had names: S-Class, Range Rover, Escalade, lined up nose to nose like prize steers. Inside, the foyer smelled faintly of lemon polish and old money. A teenage attendant in a tuxedo pointed me toward the coat check with two fingers and a smile that had been practiced in a mirror. I thanked him and kept my wrap, even though the air was warm. Habit. You don’t put down what you might need if the room turns.

The ballroom was a color most people call champagne, and carpenters call good paint. Round tables dressed in white, a bandstand draped in velvet, a dance floor polished to a nervous shine. Someone had thought of everything. Place cards in a calligrapher’s hand, centerpieces of garden roses and eucalyptus, little chalkboard signs at the bar offering signature cocktails with the couple’s names. You can tell a lot about a family by their bar menu. The Hastings had a “Hastings Old-Fashioned” with top-shelf bourbon and house-made cherry syrup. It told me they liked tradition, but only the expensive kind.

Jennifer was radiant. I’ll give her that. She wore lace that wasn’t fussy and heels she didn’t wobble in. Her hair was done in the easy way the very rich prefer, styled to look unstyled. When she saw me, she threaded through the guests like a boat clipping reeds, that smile of hers trained and warm. “You look lovely, Emily,” she said, and I nodded and told her the truth: “So do you.” Because two things can be true at once. She could be kind to me in one breath and dismiss me with the next. A person’s character isn’t the weather, it’s the map of their choices. I had learned to navigate.

The Hastings guests had that country club casualness that reads as friendliness from a distance and inventory-taking up close. I caught the sideways glances at my dress, at my shoes—polished but not precious—at my hair, pinned back the way women who prefer function over fashion do it. “There’s Mark’s mother,” I heard a woman whisper behind a program. “She looks practical.” *Practical* is what people say when they don’t want to say *plain*. I’ve been called worse.

My father arrived late, as he always did when punctuality would suggest deference. He wore a suit a shade too shiny and a tie that looked like a loud argument. He kissed my cheek and left the smell of aftershave and menthol on my skin. “Don’t cry,” he said. “Mascara will run.” It wasn’t advice. It was a reminder: *your face is a thing that can fail you in public*.

The ceremony was honest and short. The pastor kept to love and duty and avoided the kind of jokes that turned holy things into banter. Mark’s hand shook when he slid the ring onto Jennifer’s finger, and I loved him for having nerves. If love doesn’t make you tremble a little, you’re either lying or not paying attention. When they kissed, I felt my mother like a warm hand on my shoulder.

During photos, I drifted to the edge of the lawn and watched the grounds crew wheel a cart of lemonade through the shade of old oaks. Weddings are a study in logistics, timelines, backups, redundancies. I felt calmer imagining the day as a mission plan: *At 2:00 PM, move guests from chapel to ballroom. At 2:15, first round of hors d’oeuvres. At 2:30, announce wedding party.* My mind has always sought anchors in details. I suppose that’s why I got good at the work I do. Solvable things steady the unsolvable.

The reception opened the way receptions do: applause, a flurry of napkins, the band easing into something everyone recognizes so they don’t have to pretend. I was seated with two couples who play golf with the Hastings on Wednesdays. “We never miss nine and dine,” the woman to my left said. “Eighteen holes and then dinner with the same four jokes,” her husband added, and the table laughed like it was a joke to admit there were only four jokes. Small talk makes a scaffolding for the hours we don’t yet know what to do with. We discussed the weather and the roast beef and the price of flights to Naples. They asked what I did, and I gave them the soft version. “Administrative work,” I said. “Lots of planning.” It’s not a lie if it’s true, just not the whole truth. Most people want a story they can set down easily. I’ve learned to hand them something light.

The groom’s side had filled their half of the room with bankers and lawyers and a sprinkling of minor officials who hold the soft power of permits and connections. The bride’s grandmother wore a brooch that could fund a small college if you melted it down and auctioned the stones. The flower girl, bored now that there were no petals left to scatter, invented a game on the carpet that seemed to involve rescuing napkin rings from a flood. In *their* world, the room was a river. In *mine*, it was a field.

I first noticed the groomsmen at the bar, not because they were loud, but because they weren’t. There’s a quiet to men who have carried weight together, a way they lean without slumping, taken a room without scanning it. One had a scar near his temple that disappeared into his hairline. Another held his glass in his left hand but wore his watch on the right. Useful details if the night needed them. The kind of details my father would never notice because they had nothing to do with appearances.

By the time the salads had been cleared and the prime rib arrived with a flourish—jus and horseradish cream announced like dignitaries—the noise had thickened into that polite roar you get at big events. Someone clinked a glass and tried a toast. The band struck a wrong chord and recovered. A toddler near the head table executed a jailbreak from a booster seat and was wrangled like a joyful calf. It was an American wedding, beautifully ordinary in all the ways that matter.

And then my father stood.

I felt the shift before the first word. He drew himself up the way men do when they are about to ride a wave of their own making. He had not been asked to speak. I knew that because Jennifer is the kind of bride who builds run-of-show documents, and the planner tried a subtle shake of her head from the margins. He didn’t see it. He never has when the sign says *yield*. He tapped his glass with a butter knife until the clamor softened and faces turned toward him. Faces that didn’t know him well enough to dread him.

“Folks,” he said, “I just want to say a word about family.” I could have written the next five sentences from memory. They were the same ones he’d used at graduations and funerals and the odd company picnic. He always starts with a joke because jokes give him deniability. If you object, you can’t take a joke. If you laugh, you participated. It’s a neat trick if you don’t mind buying power with someone else’s dignity. He thanked the Hastings for hosting, made a crack about all this fancy food and how “in our house we called this many forks a problem,” and got a laugh that warmed him like whiskey. He gestured to Mark with a flourish and said he was proud, which was true. And then his hand found me, and I felt the light move with it.

“This,” he said, and the room was quiet enough to hear the band leader’s shoe scuff. “This is my lazy, fat daughter.”

The words were not new in their content, only in their audience. I had been called worse names by him at a gas pump, in a grocery aisle, on a church step, but words thrown into a microphone travel farther. I stood very still, because if your face doesn’t move, sometimes time doesn’t either.

Laughter broke around me like hail. Not everyone, bless the few who held themselves, but enough. Enough to scratch, enough to mark. Jennifer’s mother brought a hand to her necklace and made a small sound that might have been shock or might have been etiquette failing. A cousin coughed into his fist the way people do when they want to hide a grin. At my table, the golf husbands looked down as if salad plates had become fascinating. My son, God help him, stared at his water glass like it might tell him what to do. It is not easy to be a good son and a good man at the same time when the room asks you to choose.

I did not speak. There are fights you win by leaving them hungry.

Out of the corner of my eye, I caught the groomsmen straighten—not like soldiers, not yet, just like men adjusting the weight of a thing they might have to carry. The one with the scar murmured something to the tall one with the careful watch. The tall one shook his head once as if to say, “Not yet.” There is a choreography to intervention. You wait until the harm is clear to everyone, not just to you.

My father wasn’t done. Bullies are rarely satisfied with a single blow when the crowd is warm. He launched into a story about me at 12, about a little league fundraiser, and how I ate three hot dogs, about how “we laughed and laughed at Big Em, bottomless pit.” The details were wrong. My brother had eaten two of those. But accuracy is not the point of a performance. The point is consent.

I looked at my hands resting on the linen. My nails were plain and cut short. I had cleaned a rifle last month with these hands, signed a promotion order that changed a young sergeant’s life, held my son’s face in them when a fever scared him at 5. The same hands. The groom did not know. My father did not care.

Someone at the head table tried to redirect. “Let’s toast the bride and groom!” the planner’s assistant said, bright as a lifeguard’s whistle. My father waved the suggestion aside like a gnat. He was warming to his theme, the crowd responding in those little obliging ripples that tell a speaker he’s safe to keep going. I could map the next minute of damage before it landed.

Across the room, the groomsmen’s eyes met mine. Not for permission exactly, for alignment. I gave them the smallest nod a person can give and still be seen. They set down their glasses. They didn’t snap to attention. They didn’t salute. They just put their glasses down and spoke together, the way men do when they’ve carried rucks in the same rain.

“Sir, she’s our commanding officer.”

It wasn’t loud, but it cut. The sound left the groomsmen like a level line and sliced the ballroom clean in half: before and after; laughter and silence; ridicule and reckoning.

My father blinked as if the room had moved, and he had stayed still. Someone near the head table sucked in breath too fast and choked. A waiter froze mid-pour. A woman’s bracelet chimed the stem of her glass. My father tried to grin, then to swallow, and did both badly. He lifted his wine for the cover of motion, took a nervous sip, and the truth hit him mid-swallow. Bordeaux sprayed across the white tablecloth in a red fan. You could hear it land.

The tall groomsman, Staff Sergeant Miller—though the room didn’t need his name—kept his voice even. “With respect, sir,” he said to the space where my father’s authority had been. “Ma’am led us in Khost Province. We’d prefer you speak of her accordingly.”

*Prefer?* Such a tidy word for a line in the sand.

The band stopped pretending to vamp. The last piano note hung in the air like a moth and died. A cluster of teenagers drifted backward instinctively, the way flocks do when they sense a hawk. At my table, the golf husbands became experts on bread plates. Jennifer’s mother found her necklace again the way some people find rosary beads in rough weather. The room had hands, and every hand looked for a place to hide.

“Commanding… what?” my father said, as if syllables themselves had turned on him.

Miller didn’t answer with rank. He answered with memory. “Khost,” he said softly. “Convoy Bravo. June. Ma’am was the one who went vehicle to vehicle when the comms died. She’s the reason Lewis got home to teach his daughter how to ride a bike.” His jaw worked once, the way men do when they push back whatever it is that would make their voices break. “She’s our CO, Ma’am.”

The scarred one, Corporal Dodds, added like a punctuation mark, “Permission to clarify.”

I met his eyes. “Go ahead.”

He looked at my father. “Sir, you don’t have to like us, but you’re going to respect her.” It didn’t come out tough. It came out true, and truth has a weight that bullies can’t bench.

My father stared at me like I’d participated in a trick. For once, he ran out of script. He groped for a laugh, then for a shrug, then for his napkin, and settled for dabbing at the wine stain, as if it were the problem. “Well,” he said to no one, then to everyone, “Well, now…”

Across the head table, the best man, who had been ready with a joke about marriage being “advanced infantry,” closed his mouth and lifted his glass to hide the words. Jennifer looked from the groomsmen to me, confusion melting into calculation, into something like awe. Her father’s face, still sweating rings into the linen from his Hastings Old-Fashioned, tried on a smile of respect that had not been tailored for him yet. It didn’t fit, but he kept it on.

“Colonel,” someone whispered behind me, and the word moved across the tables as whispers do, hopping from curiosity to certainty without stopping to fact-check. I didn’t correct it. I didn’t confirm it. I let the room do the arithmetic it had failed to do for years.

The planner, God bless her, tried to restart time. She clapped once and said, “Let’s welcome our newlyweds!” with the bright courage of a person who believes sound can fix what silence broke. People clapped, but their hearts weren’t in it yet. They were too busy re-shelving what they thought they knew.

I could have stepped into the quiet and filled it. I could have recited the neatest version of a messy truth: that I had kept my rank off the holiday table because I didn’t need my father to grade it; that I had chosen privacy over performance; that I had learned there is a difference between humility and hiding. But a good officer knows when not to brief. I stood there and let their eyes do what eyes have to do before minds follow—adjust. Miller shifted an inch closer to the line of groomsmen, as if to say that if gravity failed, they would provide a substitute. Dodds’ scar caught a glint of chandelier light and made a small star. The watch on the left-handed one ticked the same tick no matter how the room felt about me. I took comfort in that. Machines keep time. Men keep faith.

My son stood, his chair legs scraped the parquet with a protest. He looked down at his hands, then up at me, then at the men who had just moved the sound in the room. He has my mother’s eyes—steady, even when the rest of him isn’t.

“Mom,” he said, soft, simple. And that was the first honor that mattered.

My father reached for bluster like a man reaches for a banister in the dark. “Just a joke,” he said, aiming for hardy and hitting hollow. “Can’t anybody around here take a—”

“Sir,” Miller said, not loud, final.

It is a strange thing to watch power move. It doesn’t thunder. It relocates quietly. Absolutely. From the mouth that misused it to the people who won’t. You could feel it settle.

A glass fell. It was small, one of the slim water ones, with a fragile base. It hit the floor and broke politely the way expensive things do. The sound was neat and decisive. Somewhere near the bar, a guest exhaled a laugh they tried to swallow and ended up coughing it into a napkin. Laughter had become risky. That is the beginning of manners.

“Jennifer,” her mother said, her voice tight. “Why didn’t you tell us?”

“Because it wasn’t my story to tell,” Jennifer answered, surprising me. “And because we didn’t ask.” So the room learned a second thing: in 10 seconds, you can be wealthy and still teachable.

The band leader, bless his mercy, chose a hymn tune in a jazz suit—something with a backbone that could hold weight—and let the pianist find a chord that said, *We can all try again*. People sat. The toddlers resumed their flood game at the edge of the dance floor. Life, which had paused to take attendance, started checking names again.

“Ma’am,” Dodds said, *sotto voce*, as if we stood in a hallway and not in a chandeliered storm. “We got your six.”

I nodded once. “I know.”

My father looked at me and found no daughter he recognized. He had always mistaken endurance for emptiness, mistaking quiet for a lack that could be filled with him. I watched the recognition climb his face like weather. And then I watched it pass. He set his jaw. He picked up his knife as if dinner were the problem, not his mouth. His hand shook just enough to catch the candlelight.

The planner approached me with the practiced smile of a nurse and the bravery of one. “We’re moving to toasts,” she whispered. “Would you like to say something?” The question was a bridge—a way for the room to cross from spectacle to sense. I could feel every eye rehearse what I might do with a microphone. I could spend this moment on revenge. I had a balance due and a live audience. But training outlasts appetite. When your soldiers intervene because your father forgot how to be one, you remember who you are responsible to.

I walked to the small platform where the mic waited, adjusted it with two fingers, and let the feedback find and lose me. “Thank you,” I said to the groomsmen first, because gratitude is the right flag to raise when you’re choosing what kind of story this becomes. Then I faced the room.

“I’m not here to correct anybody’s biography,” I said. “I’m here to celebrate two people who chose each other.” I looked at Mark and Jennifer. “Marriage is the art of honor in close quarters. You don’t have to be perfect to be honorable. You just have to tell the truth, especially when it would be easier not to.” I let my gaze pass my father without stopping. Mercy refuses to audition. “In my line of work,” I continued, “we say ‘quiet professionalism.’ Do the hard things, speak softly, and get your people home.” I lifted my glass. “Here’s to two good people getting each other home.”

The room stood. Not all at once, but in that wave that means something has been decided without a vote. They drank. The pianist found a happier key. A waiter whisked away the ruined cloth as efficiently as field medics pull a tourniquet. My father did not stand, but he didn’t speak either. Progress is sometimes subtraction.

When the applause settled, the band found a dance tune and people moved because moving is what humans do when they’ve been reminded of gravity. The groomsmen went back to being men in tuxedos with clean shoes. Dodds passed me with a nod that contained more history than the room would ever read. Miller smiled the small, unphotographed smile of a man who has seen his CO stand still in the right moment. I exhaled. The air felt earned. The night would have more negotiations and small braveries, but the shape of it had changed. I could feel it in my boots and in my bones. Power had been returned to its rightful owner, not to me, but to the truth.

The applause ended, but the silence didn’t. It lingered in the corners, heavy as humidity before a storm. Guests tried to pick up forks, to pretend the roast beef mattered, but the rhythm of dinner had been broken. Laughter doesn’t grow back easily after it’s been choked. I sat down without fanfare. Miller and the groomsmen melted back into the current like men who had never stepped out their tuxedos. Neat again, their glasses full again. But the shift they’d caused remained. The Hastings family, who had opened their home like a theater, now wore the expression of playgoers who realize they’ve been cast in someone else’s tragedy. Jennifer’s mother dabbed her mouth with her napkin as if erasing words she hadn’t said. Her father fiddled with his cufflinks, eyes darting between me and my father. My son Mark squeezed Jennifer’s hand under the table like a man clinging to the only real thing in a room that had become counterfeit.

My father busied himself with the stain on his shirt front. He poured water from a crystal pitcher onto his napkin and rubbed at the wine spots as if they were the problem, not the sentence that had caused them. He muttered something about a joke gone wrong, but no one laughed this time. Whispers moved through the crowd like smoke through rafters. *Colonel, Afghanistan, convoy.* People don’t need details. They need a headline. And the headline was enough. The woman who had been mocked had already carried more weight than most of them would see in a lifetime.

A young cousin of the bride, emboldened by champagne and youth, leaned toward me. “Is it true?” she asked. “Were you really over there?” Her tone was half awe, half gossip. I looked at her and chose kindness over spectacle. “Yes,” I said simply, “and so were many better than me.” Her eyes widened and she sat back, chastened. Sometimes humility is sharper than pride.

The band struck up a waltz, but the dance floor remained mostly empty. No one wanted to be the first to pretend normal had returned. My father chewed each bite of beef like it had wronged him. Across the room, the groomsmen talked quietly among themselves, their faces relaxed again, but their presence now unmistakable. Everyone knew they weren’t just friends of the groom. They were a testimony.

When the time came for formal toasts, the best man stumbled through a speech that had been lighthearted on paper but now sagged under the weight of the evening. He skipped the jokes. The maid of honor cried halfway through hers, and no one minded. Sentiment was safer than humor now.

And then the microphone came to me. I hadn’t planned to speak. I never do. But sometimes silence can turn into complicity, and I had lived too many years in silence. I rose slowly, felt the weight of eyes, and let them wait.

“I wasn’t planning to give a toast,” I began, “but life doesn’t always follow a plan.” A small ripple of relieved laughter, not cruel, just human, passed through the room. “What I do want to say is simple. Marriage isn’t about perfection. It’s about honor in close quarters. It’s about telling the truth when it would be easier not to. And it’s about showing respect, especially when respect is hardest to give.” I raised my glass. “So, here’s to Mark and Jennifer. May you always honor each other, not in the easy moments, but in the hard ones.”

The room stood. Glasses clinked. For the first time that night, applause came without hesitation. It wasn’t for me. It was for the reminder that dignity can be practiced, even learned in real time. My father didn’t clap. He stared at his plate, his jaw set. But he didn’t speak either. And in our family, that was progress.

Later, during the first dance, I stepped aside to the back of the room. A woman I didn’t know touched my arm. “Thank you for your service,” she whispered. Her eyes shone. I nodded, unable to answer. Praise feels strange when you’ve spent years hiding like light in a room too long dark.

By the time the cake was cut and the dance floor finally filled, the story had already traveled. Strangers approached me with questions, with gratitude, with curiosity. Some wanted details of medals and missions. I gave none. Some just wanted to shake my hand. I gave all. But the only eyes I wanted to meet were my father’s, and he avoided them all night. He slipped out early, mumbling about traffic. His empty chair at the family table was a sharper statement than anything he might have said. Still, I didn’t chase him. For the first time, I realized I didn’t need his recognition to validate my story. The truth had already stood up for me. And when truth stands, the rest of the room has to follow.

***

The morning after the wedding, the house smelled like coffee and flowers that had given up. My kitchen counter held a lineup of vases Mark and Jennifer couldn’t fit in their car, and every blossom bowed its head like it had stayed up too late. I stood at the sink with a mug in both hands and watched a sparrow bully a blue jay off the feeder. The sparrow won. Size is a poor predictor of victory.

My phone lit with messages. Old friends from town who had been at the reception wrote the kind of texts people send when they aren’t sure whether to congratulate you or apologize. *Proud of you. Sorry about your dad. Did that really happen?* I set the phone face down. The truth didn’t need replies.

Mark called around 9:00 AM. “We’re driving up to the lake for two days,” he said, his voice sanded down by fatigue. “Jen’s folks rented a cabin. You okay?”

“I am,” I said, and I meant it in the only way that matters. I could breathe without counting. “Enjoy your honeymoon sprint.”

He hesitated. “Mom, last night… what you said. Thank you for not, you know, lighting anyone on fire.”

“I offered,” I said. He huffed a laugh.

“Yeah, that.”

“I wasn’t the one who saved the room,” I said. “A few good men did.”

“They said you saved them first,” he said quietly. “I’ll call when we’re back.”

After we hung up, I wrote a short note to Jennifer: “Thank you for your answer: ‘It wasn’t my story to tell.’ ” And left it there. The bridge had weight limits. We’d test them later.

By noon, the town had metabolized the event the way small towns do: quickly, loudly, with many witnesses. The diner waitress added an extra slice of bacon to my BLT and pretended she hadn’t. At the hardware store, an older man, who never meets anyone’s eyes, paused at the end of an aisle, cleared his throat, and said, “Ma’am,” like it was a flag. I nodded back, because there are handshakes that don’t require hands.

My father didn’t call. He didn’t the next day either. On the third day, I put on my walking shoes and headed toward his shop. The roll-up door was half open. The smell of oil and old cardboard, thick as always. A radio played classic country, soft enough to be embarrassed about it. He sat on a stool at the workbench with a ledger open, pencil in his fist, like he was threatening the numbers into place. He didn’t look up when I stepped inside.

“You’re open?” I asked.

“Always,” he said.

I stood a few feet away the way you approach a skittish animal. “I brought the socket set you loaned me,” I said, and set it on the bench. “I marked the ones that were yours.”

He grunted, which in our native language meant “thank you, go on.”

“I thought we should talk,” I said.

“We talked enough Saturday,” he said to the ledger.

“No,” I said. “You talked. Then other people did. I’d like to speak now.”

He set the pencil down with exaggerated care, like a man setting a fuse. “If this is about your big moment—”

“It’s about the little ones,” I said. “Parking lots, church steps, dinners.” He flinched, not because he didn’t remember, but because he did. Silence held us like old rope. In the corner, a box fan rattled against its grill with every fifth rotation.

He finally said, “It was a joke.”

“Jokes are supposed to be funny to the person who hears them,” I said, “not just the person who tells them.” He took that like a jab and rubbed his jaw as if it had landed physical.

“People laughed.”

“And then they didn’t,” I said. “That’s the part I’d like you to keep.” His eyes slid to the radio as if the right song could offer him a better defense. When none came, he tried a different trench.

“You never said what you do. You never told me.”

“You never asked,” I said. “You filled the blanks with the story you preferred.”

He sniffed. “Military is just a job.”

“It is,” I said. “And so is fatherhood.” That one found the target.

He looked at the ledger again and said, “I gave you what I had.”

“You gave me the part of you that mocks what you don’t control,” I said. “You withheld the part that names what is good and leaves it alone.” He drummed his fingers once, twice.

“So, what do you want? An apology?”

“I want you to stop,” I said. “Not just the big performances, the small cuts, the way you say ‘big girl’ when you mean ‘beneath me.’ I want you to stop buying power with my dignity.”

He stared, and for a moment I saw the man he had been when I was five and he let me hand him wrenches. How careful he was then with names: Phillips, flathead, crescent—as if language itself was a toolbox that could fix anything. He looked older than he had in the ballroom. Maybe because we weren’t under chandeliers now. There was no stage light to lie for him.

“What if I can’t?” he said. It wasn’t a dare. It sounded like a confession.

“Then we’ll see each other less,” I said. “I will not bring myself where I am not respected. And I will not bring my son.”

He nodded once, sharply, as if taking a measurement. “You got hard,” he said, and it was almost admiration.

“I got clear,” I said.

He thumbed the edge of the ledger paper. “And if I say I’m sorry—”

“Then you’re sorry,” I said, “and we can begin again.” Beginning is not the same as erasing.

He closed the ledger, pushed it aside, and got off the stool the way men do when the floor has risen on them: slow, cautious, privately surprised the room still holds. “There’s a service at the Veterans Memorial on Saturday,” he said. “They’re dedicating a new plaque.” He paused long enough to be clumsy. “I could stand there with you.”

A simpler time would have answered for me: pride, resentment, the satisfaction of a door closed softly. But I could hear my mother’s voice in the quieter parts of me. *If he reaches, let him touch the air at least.* I nodded.

“Okay.”

Saturday was bright in that Ohio way, where the sky tries to apologize for the winters. The memorial sits on a square of grass between the library and the post office. A granite wall with names chiseled in rows, neat enough to steady you. A handful of townspeople gathered: Boy Scouts in sashes, a retired teacher with a flag pin, a woman in scrubs holding a toddler on her hip. The mayor said the expected things without embarrassing the occasion. When they uncovered the new plaque, an older Marine in dress blues saluted with a hand that trembled and a jaw that didn’t.

We stood near the back. My father had shaved. His tie was quiet. He didn’t talk. He didn’t grab my arm like he was steering me. He stood next to me as if proximity was a sentence he had to learn to pronounce. After the prayers, a few men approached to shake my hand. He let them. He did not interrupt to translate me into smaller words. On the walk back to his truck, he said, “I’ve been mean my whole life.”

“You’ve been afraid,” I said. “Mean is how afraid dresses for work.”

He grunted. “You going to fix me now?”

“I can’t,” I said. “I can only draw a map to the line you walk across.” We stopped by the tailgate and stood there like two people who had built something together and weren’t sure if it would hold. He looked at my hands.

“Those rings,” he said. “I don’t know what any of them mean.”

“Each one is a story,” I said. “Not one is a joke.” We let that sit. He nodded once, a tiny bow to a country he had not visited, but now recognized on a map.

A week later, he came by my house at dusk with a grocery sack full of tomatoes from someone’s garden. He set them on the counter and said, “You got any salt?” It is a strange thing the way contrition shows itself. Sometimes it’s grand. Sometimes it’s a tomato with a paper towel under it so it doesn’t spot your counter. We ate standing up. He told me the price of copper this week, how the new kid at the shop overtightened a valve and learned humility the honest way. I told him the sparrow had bullied the blue jay. And he said, “Huh?” Because the world had delivered a metaphor to our door, and neither of us felt like making it work any harder.

He didn’t say he was proud. That word may never live comfortably in his mouth. But when he left, he opened the screen door slowly so it wouldn’t slam. Consideration is a dialect. I’ll take it.

In church that Sunday, the same pew held us, the same window poured wheat and water over our shoulders. After the benediction, in the same parking lot that had hosted so much humiliation, a man from my father’s bowling league said, “Heard your girl gave a speech at that fancy shindig.” My father lifted his chin. “She didn’t give a speech,” he said. “She gave a standard.” He didn’t look at me when he said it. He didn’t have to. Nothing in our story was fixed forever, but the weather had changed. The climate, maybe.

In the mailbox that afternoon, I found a card with a note written in Jennifer’s neat lawyer hand. “Thank you for not making me the villain, even when it would have been easy. I’m learning.” Inside was a snapshot from the wedding—a candid the photographer had caught when I raised my glass. The light had found me in a way that didn’t feel like a spotlight, more like a window. I set the photo on the bookshelf beside a picture of my mother holding me at 6 months. Both of us serious. Both of us already practicing how to be seen without asking permission.

The phone stayed quiet that evening. The house was soft around its edges. I made tea. I breathed. I let the day end without arguing with it. There would be more conversations, more lines to draw, more tomatoes on paper towels, more Saturdays where we stood near granite and let names teach us how not to waste our own. But a truth had been said aloud in a room full of witnesses. And once a truth hears itself, it keeps speaking. I didn’t need a new father. I needed an old one to stop using me as kindling. He was learning. So was I.

By the time summer deepened into August, the story of that wedding night had made its way around town. At the diner, people asked me about the groomsmen, not about my dress size. At church, nobody called me “Big Em” anymore. They called me by my name. Respect can arrive late, but it still arrives.

My father stayed quiet for weeks after the memorial. He didn’t call, but he didn’t disappear either. I’d see his truck outside the hardware store, his figure hunched over a cart at the grocery. We orbited each other carefully, the way veterans circle after a battle they’re not ready to discuss.

The breakthrough came one Sunday afternoon at a cookout in my brother’s backyard. The men had gathered around the grill like it was a campfire, swapping the same three stories they always did. My father wandered over with a plate, nodded at the charred chicken wings, and then turned to me. “This is my daughter,” he said. Everyone looked. For a moment, I braced myself. The old script was still possible, but he didn’t smirk. He didn’t reach for a joke. He set the plate down and cleared his throat. “She runs things bigger than this grill. She takes care of people. That’s all I’ll say.” It wasn’t poetry, but it was enough.

Later that night, he stopped by my porch with a jar of pickles from a neighbor’s garden. “Figured you might like these,” he muttered. It was the closest he could come to apology. I accepted them, and we sat in rocking chairs without filling the silence. Sometimes reconciliation doesn’t sound like trumpets. Sometimes it sounds like two people agreeing not to sharpen knives anymore.

I tell you this story not to humiliate my father, but to honor what can grow even in rocky soil. He was raised in a world where men measured worth with waistlines and wallets. He passed that yardstick to me because it was the only one he had. But that doesn’t excuse the damage. Words are hammers. They shape or they shatter.

The moral isn’t complicated. Respect your children, even when they don’t look like the picture you imagined. Especially then. The body you mock might be the one carrying a pack through mountains. The quiet child you dismiss might be leading others in moments you’ll never see.

For those listening, maybe you’re a parent. Maybe you’re a grandparent. Maybe you’re someone still hearing the echo of a cruel sentence from long ago. Remember this: What you say in public can wound for decades. Or it can heal in an instant. You get to choose.

As for me, I no longer wait for my father to announce my worth. I’ve learned that honor isn’t given by family introductions. It’s lived in the way you carry yourself when the lights are on you. Still, I’ll admit he’s trying. He calls me by my name more now. Sometimes he even smiles. That’s a kind of victory.

If you’ve stayed with me to the end of this story, I’d like to ask something simple. Think about the words you use with the people you love. Think about whether they lift or whether they weigh down. And if you’ve ever been mocked, know this: You are not defined by the laughter of the room. You are defined by the truth that eventually stands beside you.

If this story touched you, I’d be grateful if you shared it with someone who might need to hear it. Subscribe if you’d like more stories like this, because each one is a reminder that dignity can be reclaimed, even after decades. And tell me in the comments where you’re listening from. I want to know how far respect can travel.

The greatest revenge isn’t a glass of wine spat across a table. The greatest revenge is reconciliation lived in a way that teaches others how to treat people better.

News

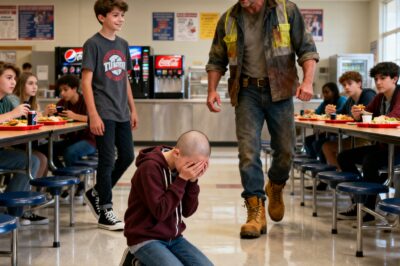

They Shoved the Boy With the Metal Leg to the Ground and Told Him to ‘Stop Acting Broken’ — Seconds Later His Father, Fresh From Special Ops, Walked Onto the Playground and Said Calmly, ‘I Just Watched My Disabled Son Get Thrown in the Dirt. If You Want to Suspend Him, Call Me. If You Want to Arrest Me, Call the Police. But We Are Leaving.’” The Principal’s Smile Disappeared on the Spot.

Chapter 1 – When the Playground Went Quiet The silence on the playground wasn’t peaceful. It felt like the silence…

The Teacher Laughed When The Girl Said ‘I Don’t Want To Reveal My Mother’s Occupation’, The Students Asked Sharply: ‘What Does Your Mother Do That You Have To Hide?’ ‘Your Mother Probably Doesn’t Have A Good Job’ — But When The Mother Appeared In A Dress With A Row Of Shining Medals, The Whole Class Just Stood Still.

CHAPTER 1 — The Question That Broke the Room It started on an ordinary Wednesday morning at Willow Ridge Middle…

They Dumped Food All Over Me and Turned Their Cameras On, Certain No One Would Ever Stop Them — Until a 4-Star General Stepped Into the Cafeteria, Looked at the Boy Holding the Phone, and Said Calmly ‘I Have Satellites That See License Plates From Space… Do You Really Think I Won’t Find Out Exactly What You Did Here?’”

Chapter 1 – The Cafeteria “Kill Box” At Crestview High, the cafeteria wasn’t just a place to eat. It was…

“Relax, It Was Just a Joke” The Rich Father Looked Me in the Eye and Said, “Kids Like Yours Don’t Belong Here” – How One Boy Ripped My Can.cer-Fighting Daughter’s Wig Off at Lunch, How His Powerful Father Tried to Silence Us, and How This Old Soldier Dad Turned One Humiliation into a Lesson the Entire School Will Never Forget

Chapter 1 – The Wig We Called “Armor” The alarm went off at 6:00 AM, sharp as a drill sergeant’s…

I TOOK CARE OF MY SICK NEIGHBOR FOR YEARS, BUT AFTER HER DEATH, THE POLICE KNOCKED ON MY DOOR – IF ONLY I KNEW WHY

For seven years, I cared for Mrs. Patterson, an elderly woman abandoned by her own family. They visited just enough…

My Husband Abandoned Me Mid-Flight With Three Crying Babies — Then the Pilot Came Out and Said, ‘May I Help You?’

My husband abandoned me in Italy with nothing to steal everything from me. But 3 days later… My husband gifted…

End of content

No more pages to load