When the World’s Largest Battleship Went Down: Yamato’s Final Hours

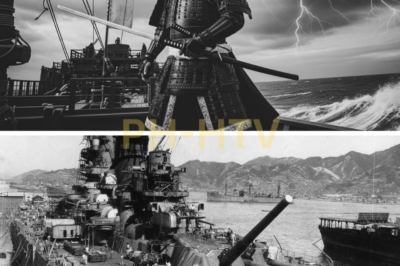

April 7th, 1945. The East China Sea. The sky was low and gray, the wind sharp, the water restless. On this morning, the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy sailed toward her fate. Her name was Yamato. Yamato was no ordinary warship. She was the largest battleship ever built in human history. At full load, she displaced more than 72,000 tons, nearly twice the weight of America’s Iowa class battleships.

Her deck stretched almost 900 ft, longer than three football fields laid end to end. Her nine main guns, 18.1 in in diameter, were the heaviest naval artillery ever put to sea. Each shell weighed more than 3,200 lb, heavier than a Volkswagen Beetle. According to US Navy intelligence reports, no American battleship could match her armor or firepower in a direct duel. To the Japanese people, Yamato was more than steel and guns.

Her very name was symbolic. Yamato is an ancient poetic term for Japan itself. She embodied national pride, the spirit of endurance, and the illusion of invincibility. Propaganda declared her unsinkable. But by the spring of 1945, reality was stark. Japan’s empire had collapsed. Its navy was shattered after late Gulf. Its carriers gone, its submarines hunted down.

Cities lay in ruins under American bombing raids. Fuel was scarce. Yamato. This so-called unsinkable fortress had spent much of the war hiding in port. Too valuable to risk, too costly to sail. Now, in April came the final decision. The Japanese high command launched Operation Tango, a desperate one-way mission.

Yamato, escorted by one cruiser and eight destroyers, would sail south toward Okinawa, where American forces had begun their largest invasion of the Pacific campaign. Yamato carried only enough fuel for the journey one way. Once there, she was to beach herself on the shoreline and fight as a stationary fortress, her giant guns blasting the American fleet until she was destroyed. Every man on board knew what that meant.

This was not a voyage of victory. It was a funeral march. More than 3,000 officers and sailors were aboard that morning. Many were veterans hardened by years of war. Others were teenagers, scarcely trained, assigned in desperation as Japan’s manpower dwindled. According to survivor accounts collected decades later, the mood aboard Yamato was a strange mixture of discipline and fatalism.

Orders were followed as always. Decks cleaned, weapons checked, stations manned. But underneath, every sailor knew they were not coming home. For the United States, the picture looked very different. By 1945, the era of the battleship was already over. Aircraft carriers, not gun platforms, had proven decisive. Coral Sea, Midway, the Philippine Sea.

At every turn, swarms of aircraft had destroyed capital ships long before their guns could come into range. Yamato, for all her size and power, was not immune to this shift. She had few aircraft of her own and no real air cover. American submarines and reconnaissance planes tracked her from the moment she left port.

By midm morning, Admiral Raymond Spruent, commander of the US Fifth Fleet, knew exactly where she was. 11 American carriers grouped as Task Force 58 were ready. Together, they carried more than 400 planes, Hellcat fighters, Avenger torpedo bombers, and Hell Diver dive bombers. For Spruent, Yamato was not simply a threat. She was an opportunity.

Destroying her would eliminate the last symbol of Japanese naval power. As US Navy historian Samuel Elliot Morrison later wrote, “Her end marked the passing of the battleship era, eclipsed by the wings of naval aviation. But imagine being on Yamato’s deck that morning. The engines rumble deep in the steel hull. Salt spray coats your face.

Somewhere beyond the horizon, hundreds of American aircraft are waiting. You know the fuel tanks are filled only for a one-way journey. You have written your last letter home. And still the ship steams forward. The Japanese high command believed Yamato’s sacrifice might inspire the nation. Even if the mission failed, it would demonstrate defiance in the face of certain defeat.

A gesture they hoped to show Japan would not surrender quietly. For the Americans, it was confirmation of something darker. That Japan would fight to the last man, the last ship, no matter the futility. If the Japanese were willing to throw away their greatest battleship and 3,000 sailors in a hopeless attack, what would happen when the home islands themselves were invaded? This fear weighed heavily on US leaders in the months that followed.

By midm morning on April 7th, Yamato’s wake stretched south across the East China Sea. Her escort ships fanned out at her sides. From above, American aircraft watched silently. One pilot later recalled, “She looked like a moving fortress, too big to believe, but she was sailing straight into our hands.” At first, there was only silence. Then came the distant hum of engines. Lookouts spotted silver wings in the gray sky. Alarms sounded.

Gunners ran to their stations. Ammunition was hauled up from magazines. Yamato’s anti-aircraft guns swiveled skyward, waiting. It was the beginning of what US Navy records would describe as the most concentrated aerial assault ever directed against a single ship. Yamato’s final day had begun.

To understand why Yamato’s last voyage carried so much weight, we need to step back years before that final day in 1945 to a time when Japan was rising as a naval power. In the years after the First World War, the great powers of the world signed the Washington Naval Treaty. It was supposed to limit the size of fleets to prevent another arms race.

The United States and Britain were allowed to keep their vast numbers of capital ships. Japan, however, was capped at just 60% of that tonnage. On paper, it was a treaty for peace. But in Tokyo, many saw it as an insult, a way of keeping Japan small, of denying her equal standing on the seas. By the mid 1930s, Japan abandoned those limits. If they could not match America ship for ship, they would build vessels so massive and so powerful that no enemy could hope to defeat them in a direct fight.

Out of that dream came the Yamato class battleships. The first was laid down in 1937 at Cure Naval Arsenal in great secrecy. Covered docks hid her from foreign eyes. Workers were sworn to silence and even many within Japan did not know what was taking shape. The Americans had suspicions but no proof. The British naval attache in Tokyo noted only that something very large was being built.

When Yamato was launched in December 1940, she proved all the rumors true. She was the largest battleship ever constructed. At full load, she displaced over 72,000 tons, nearly twice the size of the American Iowa class. Her hull stretched 860 ft, nearly the length of three football fields placed end to end. At her widest point, she spanned 121 ft, broader than a six-lane highway.

Her armor belt was 16 in thick, her turret faces 26 in, and then there were her guns. nine 18.1 in rifles arranged in three triple turrets. They were the heaviest naval guns ever mounted on a warship. Each shell weighed over 3,200 lb, heavier than a car, and could reach targets more than 25 m away. According to postwar US naval technical mission reports, no existing ship at the time could have survived a full broadside from Yamato.

To the Japanese public, she was more than a weapon. Her very name, Yamato, was an ancient word for Japan itself. She was meant to embody the spirit of the nation, a floating fortress that symbolized strength, endurance, and pride. When she was commissioned in late 1941, just days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it seemed to mark a moment of triumph.

For a short time, Admiral Isizuroku Yamamoto himself used her as flagship. In those early days of victory, Yamato was a source of national pride. But the world of naval warfare was already changing. In May 1942, at the Battle of the Coral Sea, carriers clashed without a single battleship firing a shot.

One month later at midway, four Japanese carriers were destroyed in a matter of hours by aircraft. The decisive battles that Japan’s admirals had dreamed of, where lines of battleships would exchange massive broadsides, never came. Air power, not armor, had become the deciding factor. Yamato spent much of the war tied to her peer, too costly to risk and too valuable to lose.

She sailed only rarely. When she did, her size and her appetite for fuel made her a burden on Japan’s shrinking resources. And yet, she was still seen as a symbol. To the outside world, Yamato’s very existence was a message. Japan would not be outbuilt and would not be outgunned. She finally saw serious action in October 1944 at the Battle of Ley Gulf, the largest naval battle in history.

On October 25th, in the action known as the battle off Samar, Yamato opened fire with her main guns. Survivors on the American side recalled the sea erupting in towering columns of water as her 18-in shells rained down. One US sailor remembered the sound of the shells as a freight train coming from the sky. It was the only time in history that her main battery was fired at an enemy fleet.

And yet even then her power did not decide the outcome. American destroyers, torpedo bombers, and escort carriers fought back ferociously, blunting the attack. Lady Gulf ended in disaster for Japan. Its carriers were gone, its strength shattered, and Yamato, despite her thunderous guns, returned to port, having changed nothing.

By early 1945, Yamato was more symbol than weapon. Japan was starving, its cities burning under B-29 firebombing raids, its navy broken beyond repair. Yet Yamato still loomed at her birth in Kuray, an enormous reminder of past ambitions. To the public, she represented endurance. To her crew, she was an honor. But to the men of the high command, she was a problem.

too large to hide, too valuable to waste, and yet increasingly useless in a war dominated by American aircraft carriers. And so when the order came for Operation Tango, Yamato was chosen not because she could turn the tide, but because she could die in battle. Her loss would be framed as sacrifice, her destruction used as propaganda.

As one Japanese admiral later admitted, it was not strategy, but symbolism, a gesture to prove Japan still had the will to resist. For the men aboard, that choice was both a privilege and a death sentence. To serve on Yamato was the highest honor the Navy could bestow. Yet by April 1945, every sailor knew what it meant. They were stepping aboard a steel coffin.

They were carrying their nation’s pride into a battle that could only end one way. This was the paradox of Yamato. She was the greatest battleship ever built and yet obsolete before she ever fired her first shot in anger. She was conceived as a weapon to decide wars. But in the end, she became a monument to an age already gone.

Her story is not just about steel and shells, but about the choices of leaders, the duty of sailors, and the heavy price of clinging to symbols long after they’ve lost their power. And it is in that light that we must see her final voyage. When Yamato sailed in April 1945, she carried not only her crew of more than 3,000 men.

She carried the weight of history and the burden of a nation’s pride into a sea where there would be no return. By the spring of 1945, Japan’s empire was collapsing. On land, American forces had invaded Ewoima and were pressing toward Okinawa. At sea, the Imperial Navy was a shadow of its former self. Most of its carriers were gone, sunk at Lady Gulf.

Submarines prowled the waters around the home islands, strangling supply lines. B29 bombers reigned destruction nightly on the cities. And in this desperate hour, Japan’s leaders conceived one last gesture, one last sorty that might in their minds salvage honor even if it could not salvage victory. It was called Operation Tango. The plan, conceived in early April, was grim in its simplicity.

Yamato, the largest battleship ever built, would sail south with a small escort force. She would make for Okinawa, where over 180,000 American troops had already landed. She carried just enough fuel to reach the island. Once there, she was to beach herself in the shallows and fight until destroyed. Her 18-in guns firing inland at the invasion fleet, her crew serving as a final bull work. The mission was one way, none of the men expected to return.

Alongside Yamato sailed the light cruiser Yahagi, and eight destroyers. Together, they carried a few thousand more sailors, young men who shared the same fate. In total, more than 4,000 men would steam out of Tokyama Harbor on the morning of April 6th. Survivors later recalled the farewell.

Some civilians waved from the shorelines, unaware that most of the men they were cheering would never come back. Others described a heavy silence on deck, broken only by the rumble of engines and the creek of steel. Admiral Seichi Itito commanded the operation. He understood perfectly well the odds. Japan had no air cover left.

The skies over Okinawa swarmed with hundreds of American fighters and bombers. US submarines tracked every departure from Japanese ports. And Task Force 58, 11 carriers strong, commanded by Vice Admiral Mark Mitcher, waited in the Philippine Sea with over 400 aircraft ready to strike.

Itto knew Yamato could not prevail, but he sailed anyway, obeying orders from a high command more concerned with symbolism than strategy. On paper, Yamato was formidable. She carried nine 18.1in guns, dozens of secondary batteries, and more than 150 anti-aircraft weapons. Her armor was thick enough to shrug off anything short of a torpedo or bomb hit.

Her crew numbered over 3,000, many of them trained in damage control, prepared to fight fires and flooding. If the war had been fought in 1916, Yamato might have been decisive. But in 1945, she was sailing into a world ruled by air power. The Americans knew she was coming almost immediately. Yamato could not hide. On April 6th, US submarines reported unusual radio traffic.

By the time she reached the open sea, American reconnaissance planes had already spotted her. At 8:23 a.m. on April 7th, a PBM Mariner Patrol aircraft cited the Japanese formation. The pilot radioed back a simple but historic message. Enemy battleship course south. From that moment, Yamato’s fate was sealed.

Admiral Raymon Spruent, commander of the fifth fleet, received the report. There was no hesitation. He ordered Task Force 58 to launch every available aircraft. The giant was to be destroyed before she ever reached Okinawa. Spruent knew what Yamato symbolized. Her name was Japan. To sink her would be to shatter the last illusion of naval strength the Empire still possessed.

Meanwhile, aboard Yamato, the mood was tense. Some sailors were quietly writing farewell notes intended to be passed to families if the ship made port. Others stood by their stations, silent, staring out at the gray horizon. One survivor later recalled that the atmosphere was like waiting for a storm you could not escape.

At 10:00 a.m., word reached the Japanese formation that they had been cited. Admiral Itito convened his officers. There was no doubt now. The Americans knew exactly where they were, and an attack was imminent. Still, the fleet steamed south, plowing through the choppy sea at nearly 22 knots. Yamato’s gunners stood ready.

The ship’s anti-aircraft batteries swung into position. Ammunition was stacked near the guns. Damage control teams braced for what everyone knew was coming. On the American side, the carriers came alive. Pilots strapped into cockpits. Deck crews armed Avengers with torpedoes. Hell divers with thousand-pound bombs. Hellcats with machine gun belts.

Engines roared to life across 11 flight decks. By 10:30, the first wave lifted off. 132 aircraft in all, more than enough to overwhelm the Japanese formation. As one US pilot later said, “It felt less like a battle and more like an execution.” Still, the Japanese prepared to meet it. Yamato’s guns were massive, but her real defense lay in the hundreds of smaller anti-aircraft pieces arrayed across her decks.

25 mm and 127 mm cannons, firing so fast they could fill the sky with steel. The men who manned them knew their job was hopeless, but they also knew it was all that stood between their ship and destruction. Survivors recalled that their commanders told them plainly, “Fight to the last shell.” By late morning, both sides were committed. American aircraft swarmed toward the Japanese formation, their engines growling across the sea.

From Yamato’s deck, the horizon seemed to sprout silver wings. Dozens, then scores, then hundreds of planes converging. The alarm sounded. Gun crews opened fire. The air filled with tracers and the heavy boom of flack. Sailors shouted over the roar, loading shells, swiveing barrels, tracking targets through smoke.

The giant ship shook as her big guns fired at the oncoming formations. For a moment, Yamato stood like a fortress, bristling with flame. Her gunners filling the sky with steel. But everyone aboard knew the truth. Against 11 carriers, against hundreds of planes, against a fleet that outnumbered and outgunned her in every modern way. Yamato was sailing into her last battle.

Operation Tango was not a campaign. It was a sacrifice. And as the first American bombs whistled down toward her decks, that sacrifice was about to be paid. By late morning on April 7th, 1945, the Americans had Yamato exactly where they wanted her. She was out in the open sea, far from air cover, heading straight toward Okinawa on a one-way mission.

At 8:23 a.m., the PBM Mariner Patrol Plane had broadcast its sighting report. And from that moment, the US fifth fleet began to move with precision. Admiral Raymond Spruent, a calm, deliberate commander, wasted no time. He passed the order to Vice Admiral Mark Mitcher, head of Task Force 58, the massive carrier group stationed east of Okinawa.

Mitcher was an aviator at heart, one of the men who had believed in the carrier long before most of the Navy accepted its dominance. To him, Yamato was not just a target. It was a symbol. To destroy her would be to hammer home the point that the age of the battleship was finished forever. Task Force 58 was the most powerful naval aviation force ever assembled.

11 fleet carriers, five light carriers, and a screen of fast battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. More than 400 planes stood ready on their flight decks. Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, Curtis SB2C Helldiver dive bombers, and Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo planes. They had been hammering Okinawa for days, flying strike after strike against Japanese positions.

Now, for the first time, they had a new assignment. Hunt down the world’s largest battleship and sink her before she could reach the island. The first launch came just after 10:30 a.m. Engines roared to life across 11 carriers. Deck crews armed the planes, bombs, torpedoes, machine gun belts, while sailors waved them down the deck one after another.

The sky filled with silver wings. In all, 132 aircraft took off in the first wave. A strike group larger than the entire air strength Japan could field that day. Pilots later said it felt like a swarm of hornets rising from the sea. They climbed to altitude, then dropped into formation and swept westward toward the Japanese task force.

Beneath them stretched the gray waters of the East China Sea. Somewhere ahead lay Yamato and her escorts, steaming south at 22 knots. Back aboard Yamato, lookout spotted the planes long before they arrived. A horizon that had been empty suddenly bloomed with specks. First a few, then dozens, then a cloud. The alarms sounded.

Crews rushed to their stations. Gun captains shouted orders. Ammunition crews hauled shells. The ship’s decks bristled with weapons. 127 mm dualpurpose guns. 25 mm machine cannons. Over 150 barrels in all. The men were ready. Many knew it was hopeless, but they were determined to sell their lives dearly. At 12:20 p.m., the Americans attacked.

The Avengers came in low, skimming just above the waves, releasing torpedoes that left white wakes racing toward Yamato’s hull. From above, hell divers rolled into their screaming dives. Bombs howling down from thousands of feet. Hellcats strafed the decks, their 050 caliber guns raking anti-aircraft positions. Yamato erupted in flame and thunder.

Her gunners fired furiously, tracers stitching the sky, black puffs of flack bursting among the American formations. Pilots later admitted they had never seen so much anti-aircraft fire in their lives. Several Avengers were torn apart midair, plunging into the sea.

One hell diver erupted in flame and spiraled down, crashing in a plume of steam. But there were always more. Always more. The first torpedoes struck her port side. The ship shuddered, steel plates buckling, compartments flooding. Men were thrown from their feet. Water poured in. Damage control parties raced to seal hatches to pump out compartments. But the hits were heavy.

Within minutes, Yamato began to list five degrees to port. Officers ordered counter flooding on the starboard side to balance the ship, and for a time, it worked. The giant steadied herself, but the Americans were not finished. Dive bombers dropped their loads directly onto her decks, tearing holes in the superructure, igniting fires.

One bomb struck near the aft turret, killing dozens of gunners in an instant. Another ripped into the forward deck, sending fragments sthing through crews below. Survivors later remembered the ship groaning like a wounded animal, shaking with every impact. By 12:45, Yamato had already taken multiple bomb and torpedo hits. Smoke poured from her decks.

Fire raged across her midsection. Still, she fought. Her guns kept blazing. Her crew kept running hoses, sealing compartments, hauling the wounded. One American pilot, circling above, recalled seeing gunners still firing even as flames engulfed their stations. They didn’t stop, he said. They fought until the flames took them. The battle was not only between Yamato and the aircraft.

Her escorts fought desperately, too. The light cruiser Yahagi maneuvered violently, dodging torpedoes, her guns blazing, but she became a prime target. By 100 p.m., she had been struck by both bombs and torpedoes, fires raging stem to stern. She slowed, then rolled, and within an hour, she was gone, capsized and sinking beneath the waves.

The destroyers around Yamato laid smoke screens, fired anti-aircraft bursts, and even tried to draw attacks away. Some succeeded briefly. Several were hit themselves, battered and burning. The sea around the Japanese formation became a patchwork of fire and smoke, ships twisting, shells bursting, planes diving. For the Americans, the scene was overwhelming. Pilots spoke later of awe and dread at what they saw.

From above, Yamato looked like a volcano at sea, explosions bursting across her decks, smoke pouring skyward. Yet, she refused to stop. She turned slowly, guns firing, smoke trailing behind her, the giant fighting on. By 1:20 p.m., she had been hit by at least four torpedoes and several bombs. Her port side was badly torn.

The list increased again, now over 10°. Damage control fought furiously, pumping water, counter flooding. For a brief moment, the crew managed to steady her once more. But with every strike, the damage multiplied, and still the waves kept coming. A second strike group swept in. More torpedoes raced across the sea. More bombs slammed into her deck.

The Americans were systematic. They targeted her port side again and again, deliberately worsening the list, planning to roll her over. It was not random destruction. It was calculated annihilation. By early afternoon, Yamato was staggering. Fires burned out of control. Her speed dropped. Her list worsened. Hundreds of men were dead or wounded.

Yet still, she had not fallen. Pilots reported back in disbelief. They had poured more bombs and torpedoes into this ship than into entire convoys, and she still fought. One pilot summed it up simply. She was the toughest target I ever saw. But even the mi

ghtiest fortress has a breaking point. By 1:30 p.m., the giant battleship was mortally wounded. The sea poured into her port side faster than pumps could expel it. Her escorts were sinking or scattered. Above her, more American planes circled, readying another round. The storm was far from over for Yamato. The response had been overwhelming. Against 11 carriers and hundreds of aircraft, she had no chance.

The Americans had shown once again that the age of air power had arrived, and the age of the battleship was ending. And as the clock pushed past midafter afternoon, the great ship’s struggle entered its final desperate hours. By early afternoon on April 7th, 1945, the storm had broken in full. Yamato was already battered, fires on her decks, smoke pouring from her superructure, compartments flooding deep within her hull.

She had taken multiple torpedo and bomb hits. Her cruiser escort Yahagi was sinking a stern and several destroyers were crippled. Yet the giant battleship still fought on. Her guns hammering the sky, her crew battling flames and rushing water. The Americans pressed the attack relentlessly. After the first wave of 132 planes, a second wave closed in, this time concentrating on Yamato herself.

The plan was deliberate. US Navy afteraction reports confirmed that pilots had been instructed to strike her port side again and again, forcing the ship to list so badly she would capsize. It was calculated destruction, not random chance. The torpedo planes came in low, skimming just above the sea.

Each Avenger carried a Mark13 torpedo, almost 2,000 lb of steel and explosives. From Yamato’s deck, sailors watched the silver shapes drop into the water and streak forward, leaving trails of white foam. Some missed, exploding harmlessly in the distance. But others struck home. The ship jolted violently as more torpedoes slammed into her port side. Steel buckled, compartments collapsed.

Below deck, men were hurled off their feet, scalded by steam as pipes burst. Water roared into the lower decks. The list increased again, 10°, then 15. Damage control parties fought desperately, sealing hatches, manning pumps, counter flooding compartments on the starboard side to balance the weight. For a moment, it seemed to work. The ship steadied herself, but the price was terrible.

More compartments on the starboard side flooded intentionally. More men trapped as the sea poured in above. The dive bombers added their weight to the attack. Hell divers screamed down from thousands of feet. Bombs whistling. Explosions tore across Yamato’s decks. One struck near the forward turret, killing dozens instantly.

Another ripped into the command bridge, shredding steel and hurling officers to the floor. Fires ignited everywhere. Black smoke rose so high that pilots later said it was visible for miles. A column marking the place where the giant was dying. Still, the guns did not fall silent. Yamato’s anti-aircraft crews kept firing even as flames licked their positions.

Survivors remembered comrades burning alive, refusing to abandon their posts, hands locked to the grips of their guns. American pilots circling above saw men silhouetted against fire, still firing upward until the very last moment. One US aviator later said with awe, “They fought like demo

ns. I will never forget it.” By 1:30 p.m., Yamato had been struck by at least eight bombs and seven torpedoes, according to postwar US Navy assessments. Her speed had dropped to less than 10 knots. She listed heavily to port. her decks tilting so sharply that sailors struggled to stand. Water sloshed across the deck plates. Fires burned uncontrolled below.

Yet Admiral Seichi Itito remained aboard, still commanding, still refusing to order abandoned ship. The men knew what that meant. They were expected to fight until the end. The destroyers tried to help. Some darted alongside, spraying hoses, pulling survivors from the sea. Others laid smoke screens, hoping to shield Yamato from another wave of attackers.

But they too were under assault. Several were hit by bombs. One was left a flame, its crew abandoning ship. The Japanese formation was disintegrating piece by piece while Yamato endured the brunt of the American fury. At 1:40 p.m., another torpedo struck her port side. This one tore into engineering spaces deep within the hull.

The list grew sharper. Now she leaned more than 20°. Heavy guns could no longer depress to fire. Shells and powder charges began to slide inside their magazines. Dangerous cargo shifting in ways no crew could control. The ship groaned under the strain, her massive bulk twisting as water flooded faster than pumps could expel it. Inside, the scenes were apocalyptic.

Men stumbled through tilted passageways, the floor becoming the wall, the wall, the floor. Darkness closed in as power failed, emergency lights flickering red. Some compartments were sealed off to contain flooding, condemning those inside. Survivors later recalled hearing pounding from the other side of watertight doors.

Comrades trapped, begging to be let out even as water rose to swallow them. In the smoke and chaos, damage control crews worked until the very end. Many never emerged. On deck, the devastation was just as terrible. Fires raged unchecked, consuming oxygen, choking men with black smoke. The once proud battleship was a furnace. Yet still she moved forward. Still her guns barked at the sky.

From the air, American pilots watched with a mixture of awe and disbelief. They had never seen a ship endure so much punishment and remain afloat. One hell diver pilot later remarked, “She seemed impossible to kill, but we knew she couldn’t last.” By 2 p.m. Yamato was staggering. She had taken enough damage to sink any other ship in the world several times over. Her list had worsened to 25°.

Her speed was nearly gone. The escorts were scattered or sinking. The sky above remained full of American planes, circling, preparing yet another strike. For the men aboard, hope was gone. Some began leaping into the sea, choosing the cold water over fire and steel. Others clung to their stations, unwilling to leave the guns.

And still the onslaught continued. More torpedoes, more bombs, more explosions tearing into her hull, ripping her apart. By 2:15, Yamato was mortally wounded. Her forward magazines were on fire. Her list was now so severe that the deck guns were useless. She was no longer a warship. She was a burning hulk, drifting, waiting for the end.

In those moments, the American pilots knew the battle was won. The giant had been brought to her knees. But the final act had not yet come. Yamato’s death throws were still ahead, and when they arrived, they would shake the sea and scar the memory of every man who witnessed them.

By 2:00 in the afternoon on April 7th, 1945, Yamato was dying. Hours of relentless attack had left her gutted, fires raging stem to stern, compartments flooded, hundreds of men dead or wounded. She had taken at least eight bomb hits and more than 10 torpedo strikes, most concentrated along her port side.

The giant battleship, once the pride of the Imperial Navy, now limped forward at barely a crawl, listing heavily, smoke pouring skyward like a beacon. Survivors later recalled that inside the ship, chaos rained. Passageways were twisted. Lights flickered or went dark. Men stumbled through tilted decks that felt more like walls. Water surged through ruptured compartments.

Damage control teams pumped furiously, but it was no use. Pumps were overwhelmed, and counter flooding only delayed the inevitable. Every minute, the list grew worse. At 2:10 p.m., the tilt was so severe, over 20°, that guns could no longer bear properly. Shells rolled from their racks. Loose equipment slid across the deck.

Officers realized the end was near. Some began to order abandoned ship. Others stayed at their posts, unwilling to leave their stations. Admiral Seichiito, the fleet commander, refused to save himself. Witnesses later said he remained calm, still on the bridge as chaos consumed the ship. He had told his staff earlier that he would share Yamato’s fate.

And so, while some junior officers urged him to escape, Itto stayed. He would die with his ship as tradition demanded. The Americans circling above could see it clearly now. Yamato was finished. Yet still more aircraft dove in for final strikes, hammering her again. More torpedoes ripped into her port side.

More bombs tore through her deck. One pilot described it as beating a corpse, but making sure it never rose again. By 2:20 p.m., the list had reached nearly 30°. Men tumbled across the deck, sliding into the sea. Anti-aircraft gunners clung desperately to weapons tilted skyward, still firing as flames licked at their positions.

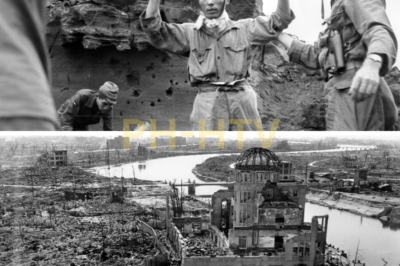

Pilots watching from above saw sailors running along the slanted decks, some leaping into the water, others refusing to leave. One remembered seeing gunners still at their posts, even as waves washed across the deck. At 2:23 p.m., the order was finally given to abandoned ship. But for most men, it was too late.

The sea was already swallowing Yamato. Lifeboats were useless, blown apart, or impossible to lower on the tilting hull. Men simply jumped. Some were pulled into burning slicks of oil. Others clung to wreckage, choking on smoke and seaater. Of the more than 3,000 men aboard, only a few hundred would survive. Then came the final moment.

At approximately 223, flames reached the forward magazine where tons of shells and powder charges were stored. The explosion that followed was cataclysmic. Witnesses, both survivors in the water and American pilots overhead, described a fireball that rose miles into the sky, US Navy reports estimate the column of smoke climbed more than 6,000 m, visible over a 100 m away.

The battleship, already listing heavily, rolled sharply to port, capsized, and then erupted in a colossal detonation. The sea itself seemed to convulse. The blast sent shock waves across the water, overturning small boats and knocking men unconscious. A mushroom-shaped cloud, reminiscent of what the world would later see at Hiroshima, towered above the East China Sea.

Debris rained down for minutes. Survivors spoke of twisted steel raining into the waves, fragments of turrets, planks, and human remains scattered across the surface. One American pilot called it the most terrifying sight of the war. By 2:25 p.m. it was over. Yamato was gone. The Pride of Japan, the largest battleship ever built, had sunk beneath the waves, broken in two, carrying with her over 3,000 souls. Only 276 men would live to tell the tale.

For the Americans, the victory was decisive and symbolic. Task Force 58 had proven beyond doubt that air power, not battleships, now ruled the seas. No matter how large, no matter how powerful, no warship could withstand the concentrated fury of carrier-based aviation. Yamato’s death marked the twilight of the battleship era.

For the Japanese, the loss was catastrophic. It was not just the death of a ship. It was the death of an idea. the dream of decisive battle, of steel fortresses deciding empires. Yamato had been more than a weapon. She was a symbol of national pride, of endurance, of hope, and in a single afternoon, she was gone.

The survivors clung to wreckage, dazed and wounded. Some were pulled aboard the few remaining destroyers. Many floated for hours before rescue. They carried memories that would haunt them for the rest of their lives. The screams of men trapped below deck. The sight of comrades burning at their guns.

The sound of the final explosion that ripped their world apart. Decades later, many still wept when they spoke of Yamato. The Americans too remembered. Pilots returned to their carriers shaken. They had destroyed the largest battleship ever built. But what they had witnessed left them quiet. One pilot wrote later, “I watched a nation sink that day.

In less than two hours, the symbol of Imperial Japan’s naval power had been erased. Yamato, whose name meant Japan itself, had joined the sea. The East China Sea grew calm again. Waves closing over the twisted wreck below. Oil slicks spread across the surface. Lifeless bodies drifted amid debris. Above the smoke still rose, a grim marker visible for miles.

And far away in Japan, families would soon begin to receive the silence that follows when letters never come. For history, Yamato’s last moments stand as both tragedy and lesson. Tragedy because thousands of young men died in a hopeless gesture, sacrificed for symbolism. lesson because her end proved decisively that size and power meant nothing against the new reality of war.

The Tatio battleship era had died with her. The carrier era had taken its place. By 2:30 p.m. on that April afternoon, the world had changed, and in the quiet that followed, only the sea bore witness to the final fall of Yamato. When the echoes of Yamato’s explosion faded, the East China Sea was a graveyard. Oil slicks spread across the waves, shimmering black under the pale sun.

Lifeless bodies drifted among shattered timbers and twisted fragments of steel. The once mighty battleship, Pride of the Imperial Navy, was gone. In less than 2 hours, she had been annihilated, and with her more than 3,000 men had perished. For the survivors, the ordeal was not yet over.

A handful of destroyers, bloodied but still afloat, circled back to rescue those clinging to wreckage. Flames still licked their decks, and bombs had torn gaping wounds in their hulls. But the captains ordered their crews to pull men from the water. Amid the chaos, sailors hauled exhausted comrades over the side, cutting away oil soaked uniforms, pouring fresh water into salt choked mouths. Many of the rescued were burned or broken.

Some were so stunned they could not speak. Out of Yamato’s crew of more than 3,000, only 276 were saved. The rest were swallowed by the sea. Admiral Seichi Itito was not among them. True to his word, he had gone down with his ship, a symbol of devotion, but also of futility. His death, like Yamato’s, was both an act of loyalty and a gesture without effect.

The battle was over almost as soon as it had begun, and Japan had sacrificed its last great ship for nothing. The American pilots returned to their carriers subdued. They had carried out their orders flawlessly. Task Force 58 had unleashed more than 300 aircraft in successive waves, and the result was beyond dispute. The world’s largest battleship destroyed.

Her escorts shattered. The last flicker of Japan’s naval power extinguished. Yet in their reports and letters home, many aviators admitted to mixed feelings. One pilot described watching the great ship capsize as like watching a mountain sink. Another wrote in his diary that night, “We destroyed her, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that we were watching men die for no reason.

It was victory, but it didn’t feel like triumph. In Japan, the news did not come at once. The high command suppressed reports of Yamato’s sinking. To admit her loss so soon after Okinawa had begun would have been too great a blow to morale. Families of the sailors received no word. Mothers and wives waited for letters that would never arrive.

Only after the war ended did many learn the truth that their sons and husbands had gone to sea on a mission from which they were never meant to return. For those who survived, the memories were unbearable. In postwar interviews, former sailors wept as they recalled comrades trapped below decks pounding on steel doors as the ship flooded, begging to be let out.

They spoke of flames that consumed gun crews, of men still firing anti-aircraft weapons as the deck tilted beneath them. Some described the final explosion in words that faltered, the fireball rising miles into the sky, the blast hurling them into the sea. Even decades later, the grief remained raw. “We were children,” one survivor said. “They sent us to die, and we did.

” Strategically, Yamato’s loss changed nothing. The battle for Okinawa raged on. American forces continued their assault, enduring kamicazi strikes and brutal resistance ashore. But the destruction of Yamato carried enormous symbolic weight. For the Americans, it was confirmation of what they already believed, that the battleship was obsolete and that air power had transformed naval war forever.

For Japan, it was the shattering of a myth. The ship that bore the nation’s name that had been said to be invincible had not lasted 2 hours against American carriers. Her death was the death of the Old Navy itself. In Washington, analysts noted the significance. Reports from Task Force 58 highlighted the scale of the strike.

Hundreds of planes, coordinated waves, precision torpedo runs, and concluded that no surface fleet could hope to survive without air cover. Admiral Chester Nimttz remarked simply, “The battleship went down fighting.” But her day was done. For American leaders planning the next phase of the war, the lesson was stark.

If Japan would send its greatest ship and thousands of men to die in a hopeless gesture, then an invasion of the home islands could only mean bloodshed on a scale unimaginable. Back in Japan, the silence weighed heavily. Newspapers printed nothing about Yamato. Rumors spread quietly, stories of a great loss, of ships not returning. Families of the fallen were left in the dark. Only in August, when the war ended, did the truth emerge fully.

By then, the men of Yamato were gone. Their sacrifice one more piece of a tragedy that had engulfed the nation. The sea, however, remembered. Fishermen reported oil slicks and drifting wreckage for weeks. American reconnaissance confirmed the area where she had gone down. Yet, the wreck itself lay undisturbed until decades later.

In the 1980s, Japanese expeditions located her remains nearly a thousand ft below the surface, broken in two by the final explosion. Cameras sent down captured haunting images. A massive turret toppled into the sand. Steel twisted like paper. Fragments of the ship scattered across the seabed. For the families of the dead, it was both painful and consoling.

At last, they knew where their loved ones rested. For historians, Yamato’s end was a lesson written in fire. She had been the greatest battleship ever built, and yet her power meant nothing against swarms of aircraft. Her destruction was proof that technology and doctrine had shifted forever. In classrooms at Anapapolis and other navalmies, her fate became a case study.

Bigger is not always better. And clinging to obsolete ideas can doom even the mightiest force. But beyond the strategy, beyond the symbols, what remains is the human cost. Over 3,000 men died in less than two hours. They were sons, brothers, fathers. Many were teenagers, scarcely trained, flung into the furnace of war in its final desperate phase. Their courage was real, even if the mission was hopeless.

They fought their ship until she rolled and exploded beneath them. They died not because they could win, but because they were ordered to die. In the aftermath of April 7th, 1945, the sea closed over Yamato and her men. The war continued. Battles raged. Cities burned. But for those who were there, that day left an indelible scar.

As one American pilot put it, years later, when Yamato went down, an age went with her. When Yamato vanished beneath the waves on April 7th, 1945, more than just a ship was lost. With her went thousands of men, the pride of a navy, and an entire vision of how wars were meant to be fought.

In the span of a few hours, history had turned a page, and the age of the battleship, an age that had dominated naval thought for half a century, ended in fire and smoke. For the Americans, the lessons were immediate. Task Force 58’s reports were blunt. Concentrated air power had destroyed the largest, most heavily armored warship in existence. No battleship, no matter its size or its guns, could stand against waves of carrier aircraft.

Admiral Nimttz remarked in later conversations that Yamato’s sinking confirmed what Midway and Lady Gulf had already shown. The aircraft carrier, not the battleship, was now the true capital ship of the seas. At Annapapolis and in Navy classrooms across the United States, the case became a touchstone. Bigger was not necessarily better.

Mobility, flexibility, and air dominance mattered more than armor or caliber. For Japan, the lessons were darker. Yamato’s death was never widely broadcast to the public during the war. Newspapers said nothing, and families of the dead received only silence. The high command feared the impact the truth would have on morale. Only after surrender in August did the full story emerge.

And when it did, it left a deep scar. For many Japanese, Yamato became a symbol not only of pride, but of futility, a monument to the waste of lives in a war that could no longer be won. The survivors carried that burden for the rest of their lives. In interviews decades later, men who had been pulled from the sea wept as they recalled comrades trapped below decks, pounding on sealed hatches as water rushed in.

Others remembered the final explosion, a blast so vast it hurled them into the sky before the sea swallowed them again. “We were not soldiers,” one said softly. “We were children, and they sent us to die.” Their memories became part of Japan’s post-war identity, a reminder of the cost of blind obedience, of the tragedy of sacrifice without purpose.

In the decades after the war, Yamato took on a life beyond history. She became legend. Books, films, even anime would later resurrect her story. To some Japanese, she represented lost honor, a kind of tragic nobility. To others, she was a warning of the folly of clinging to symbols long after their meaning had vanished.

At Cure, where she had been built, a museum was established. Visitors walk past models of her towering turrets and marvel at the scale of her armor. For many, standing there is to confront both pride and grief, to see and steal the contradictions of a nation at war. On the seafloor of the East China Sea, her remains still lie.

In the 1980s, Japanese expeditions located her wreck nearly 1,000 ft below the surface. The images they captured were haunting. A massive turret lying in the sand, hull plates twisted and torn, fragments of the once proud battleship scattered across the seabed.

For the families of the dead, the discovery was painful but consoling. At last, they knew where their sons and husbands had come to rest. In the United States, Yamato’s fate became part of the larger story of the Pacific War. For American veterans, the memory was a strange one. Awe at her sheer resilience, pity for the men who went down with her, and respect for the courage with which she fought.

One pilot who survived the war put it simply years later. She was our enemy, but no one could watch her die and not feel the weight of it. Strategically, her loss made little difference. Okinawa was decided by the strength of American armies and the fury of kamicazi attacks, not by a single ship.

But symbolically, her end carried enormous weight. For Japan, Yamato’s destruction was the death of illusion. For the United States, it was vindication of doctrine. For the world, it was proof that warfare had entered a new age. And yet, beyond the lessons of strategy and technology, Yamato’s legacy endures as a human story. She was not just steel and guns.

She was thousands of lives bound to her fate. Most of them died in the fire and water of that April afternoon, lost to a cause that was already hopeless. Their sacrifice reminds us that wars are not only won or lost by machines, but by people. People whose courage and suffering echo long after the battles end.

Today, when visitors stand at memorials in Cure or watch grainy footage of Yamato’s last voyage, they are reminded not only of a ship, but of an era. The battleship had once been the symbol of naval power, a floating fortress meant to decide the fate of nations. With Yamato sinking, that era ended.

Carriers and aircraft had taken its place. The world had moved on. But the men of Yamato remained, caught forever in that moment when steel met fire and history shifted course. In the quiet of the East China Sea, where the waves roll endlessly, Yamato still lies in silence. For some, she is a monument to pride. For others, to tragedy, but for all, she is a reminder.

Symbols can inspire, but they cannot change reality. And when leaders sacrifice lives for symbols, it is always the young who pay the price. On April 7th, 1945, Yamato carried with her not just the hopes of a navy, but the illusions of a nation. In her death, those illusions burned away, and the world stepped fully into a new age, an age of carriers, of air power, of nuclear shadows soon to come.

Yamato’s legacy is not just the steel that lies on the seabed. It is the story of what happens when pride blinds strategy and when symbols are mistaken for salvation.

News

ch2-ha-The Sinking of IJN Musashi — How Airpower Crushed the World’s Largest Battleship –

The Sinking of IJN Musashi — How Airpower Crushed the World’s Largest Battleship – October 24th, 1944. The Sibuan Sea…

ch2-ha-How the F6F Hellcat Shocked Japanese Pilots with Lethal Superiority in WWII

How the F6F Hellcat Shocked Japanese Pilots with Lethal Superiority in WWII In the pre-dawn blackness of June 19th, 1944,…

ch2-ha-The Fatal Elevator Jam That Turned Taiho Into a 30,000-Ton Gas Bomb

The Fatal Elevator Jam That Turned Taiho Into a 30,000-Ton Gas Bomb 1430 hours, June 19th, 1944. Deep inside the…

ch2-ha-The Weapon Japan Refused to Build — That Won America the Pacific

The Weapon Japan Refused to Build — That Won America the Pacific The Pacific was an ocean of paradoxes. Japan…

ch2-EVERYONE SAID HIS LOADING METHOD WAS BACKWARDS — BUT ONCE THE SHERMAN FACED FOUR PANZERS, IT CHANGED THE ENTIRE BATTLE.

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes At 11:23 a.m. on…

ch2-ha-The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

The other Allied commanders thought he was either lying or had lost his mind. The Germans were laughing, too. Hitler’s…

End of content

No more pages to load