What German Soldiers Said When They First Fought Gurkhas

Tunisia, March 1943. The darkness is absolute. Oberrighter Hunts Vber crouches in his foxhole, rifle across his knees, listening. The Africa Corps has been in North Africa for 2 years now, and he knows the sounds of the desert night, wind over sand, the distant rumble of vehicles, sometimes British patrols.

But tonight, something is different. The silence is too complete. Even the wind seems to have stopped. Wayber’s hands tighten on his mouser. 30 m to his left, he knows Corporal Dietrich is posted. To his right, Private Kesler. They’re strung along this defensive line south of Metine, waiting for Montgomery’s eighth army to make its move. Then he sees them.

Not hears them, sees them. Four shapes moving through the darkness, low to the ground, impossibly quiet. Weber’s breath catches. They’re small, these soldiers. Much smaller than the British troops he’s fought before. They move like shadows, like they’re part of the desert itself. One of them passes within 10 m of his position.

Wibber doesn’t move. Can’t move. Every instinct screams at him to fire, to shout a warning, but something deeper keeps him frozen. These men move with a confidence that terrifies him. They know he’s here. He’s certain of it. They know. And they’ve decided he’s not worth killing yet.

The shapes disappear into the darkness toward the German lines. 5 minutes later, the screaming starts. Weber learns three things that night. First, Corporal Dietrich is dead. His throat cut so precisely he never made a sound. Second, the small soldiers are called girkers and they come from mountains so high the snow never melts. Third, the war in North Africa has just become very different.

6 months earlier, German intelligence officers in Tripoli had compiled reports on the forces they’d be facing as Raml pushed deeper into Egypt. The assessments were methodical, clinical. British infantry well-trained, disciplined, but predictable. Australian troops aggressive, excellent in defense, prone to frontal assaults. South African units mechanized, modern, effective in open terrain.

And then, almost as an afterthought, Indian divisions. The intelligence summary was dismissive. Colonial troops, it noted, recruited from subject peoples, likely to have morale problems. Limited education may break under sustained pressure. The report devoted more space to British tank specifications than to the tens of thousands of Indian soldiers already in theat.

Hedman Friedrich Müller, reading these reports in his command tent outside Tobrook, had nodded in agreement. He’d fought in Poland, in France. He knew what real soldiers looked like. They were tall, well-fed Germans, or at least they were Europeans. The idea that small men from Asian mountains could match German infantry seemed absurd.

The first German soldiers to encounter Girkas in combat were part of the 21st Panza Division probing British positions near City Bari in December 1941. The action was minor, a reconnaissance in force. A German infantry company advanced on what appeared to be a lightly held position. They found it defended by a company of the second battalion, Seventh Girka Rifles.

Leighton and Klaus Zimmerman led the assault. His afteraction report filed 3 days later was notably different in tone from previous assessments. The enemy soldiers, he wrote, were approximately 160 cm tall. They wore British uniforms, but fought with a ferocity he had not previously encountered.

They did not withdraw when flanked. They did not surrender when surrounded. In one instance, a wounded Girka soldier, both legs shattered by machine gun fire, continued firing until killed. The German company took the position. It cost them 43 casualties to dislodge 78 defenders. Zimmerman’s report concluded with a single line that would be repeated in various forms throughout German assessments for the rest of the war. These are not colonial troops.

But it was the night fighting that truly terrified the Germans. The Girkas had been conducting night raids since their first days in British service in 1815. It was a tradition refined over generations. They moved in darkness like other men moved in daylight and they carried a weapon that haunted German soldiers nightmares.

The kukri. The kukri is a curved blade roughly 18 in long, heavy at the tip. It’s designed for a single purpose to cut with maximum efficiency. In a girker’s hand, it can remove a head with one stroke. German centuries began to be found at dawn, killed so silently that soldiers sleeping 5 m away had heard nothing.

Gerright Anton Richter stationed near Elamine in July 1942 wrote a letter home that was intercepted by British intelligence and later filed in military archives. We call them the little men from the mountains, he wrote. They are no taller than boys, but they fight like devils. Last week they came into our lines at night.

We found four of our men in the morning, all dead, all with their throats cut. No one heard anything. Not a shot, not a shout. The British send them to make us afraid. And it is working. The German response was to double the sentries, then triple them, then to keep entire squads on alert through the night, rotating every 2 hours to prevent exhaustion. It helped, but not much.

The Girkas adapted. If they couldn’t reach the sentry silently, they’d probe the defenses, map them, report back. The next night, a different section of line would be hit. By the time of Elmagne in October 1942, German intelligence had revised its assessment of Indian troops. A report dated October 15th, 1942, circulated to divisional commanders noted that certain Indian units, particularly those designated as GA battalions, should be considered elite troops.

The report recommended treating positions held by Gorkers with the same caution as positions held by British guards, divisions, or German paratroopers. This was an extraordinary admission. The Vermacht did not casually compare colonial troops to its own elite forces. The respect was born from accumulated experience battle after battle. At Ruisat Ridge in July 1942, the second battalion fourth Girka rifles held a position against repeated German attacks for 3 days.

When finally overrun, the Germans found that the Girkas had fought to the last man. Not a single prisoner was taken who wasn’t wounded too severely to resist. At Medaan in March 1943 where Hans Vber had his first encounter. The first battalion 9th Girka rifles conducted a night raid that penetrated 300 m into German lines, killed or wounded over 40 soldiers, destroyed two ammunition dumps, and withdrew without losing a single man.

The psychological impact was cumulative. German soldiers began to dread night duty when facing Indian divisions. The darkness, which had once been an ally, became a source of terror. Every shadow might contain a small man with a curved blade. Every sound might be the last thing you heard.

Obust Heinrich Brandt, commanding a regiment in Tunisia in early 1943, recorded in his diary an incident that captured the strange mixture of fear and respect German soldiers felt. A Girka soldier had been captured during a daylight action, wounded but alive. Brandt visited him in the field hospital. The man was perhaps 22 years old, no more than 5’4, with a round face that looked almost boyish.

He’d been shot through the shoulder and had lost a significant amount of blood. Brandt, who spoke some English, asked him why he fought so fiercely for the British. The Girka’s answer, translated by a medical orderly, was simple. It is better to die than to be a coward. Brandt wrote that night.

This small man who could be mistaken for a child at a distance has more warrior spirit than half my regiment. We have been fooled to underestimate these soldiers. They are not fighting for the British Empire. They are fighting because they are warriors and warriors do not surrender. The respect went both ways. Though the Germans discovered this in an unexpected manner.

After the fall of Tunis in May 1943, thousands of German soldiers became prisoners of war. Many were guarded by Indian units, including Girkas. The German PWs, expecting harsh treatment, were surprised to find their guards professional and in some cases almost friendly. A German sergeant named Otto Becka, captured near Infidaviel, later described his first encounter with Girka guards.

He’d been terrified, remembering the stories of night raids and kukri blades. But the girkers treated the prisoners correctly, even sharing their rations when supplies were short. Becca asked one of them through a translator why they’d fought so hard. The Girka soldier smiled. “You are brave soldiers,” he said.

“We respect brave soldiers. The fighting is over now. Now we are just men. This distinction between the warrior in combat and the man in peace was fundamental to Girka culture. German soldiers raised in a military tradition that also valued warrior virtues began to understand. The Girkas weren’t savage.

They were professional soldiers who took their craft seriously. In battle they were implacable. Outside battle they were human. But the war wasn’t over. It moved to Italy. The Italian campaign beginning in September 1943 brought German and Girka soldiers into contact in terrain that favored the defenders. Mountains, narrow valleys, fortified positions.

The Germans, masters of defensive warfare, prepared elaborate positions along the Gustav line, the Hitler line, the Gothic line. The Girkas, who came from mountains that made the Aenines look like foothills, were in their element. At Monte Casino in early 1944, the first battalion 9th Girka rifles fought in some of the most brutal combat of the war.

The slopes were steep, rocky, exposed to German fire from above. The Girkas advanced uphill, sometimes crawling, sometimes rushing from cover to cover, always moving forward. Gerriter Ludvig Hartman defending a position above the Rapido River watched a Girka attack develop one morning in February 1944. The small soldiers moved up the slope in short bounds using every fold in the ground. German machine guns opened up.

Men fell. The attack continued. More men fell. Still they came. Hartman who had fought on the Eastern front and thought he’d seen everything was shaken. They don’t stop, he told his squad leader. You kill them and they keep coming. What kind of men are these? His squad leader, a veteran of North Africa, didn’t look up from his machine gun.

Girkas, he said, “Just keep firing.” The attack was eventually repulsed, but at a cost that shocked the German defenders. For every Girka killed, they’d expended hundreds of rounds of ammunition. The small soldiers didn’t present easy targets. They were trained from childhood in mountain terrain. They could move across slopes that seemed impossibly steep, find cover where none appeared to exist, and at night they owned the mountains.

German positions in Italy were subjected to constant Girka night patrols. Not the large-scale raids of North Africa, but smaller, more focused operations. A listening post would be hit. A supply route interdicted, an observation post cleared. Each operation was executed with precision and withdrew before German reinforcements could respond.

The psychological strain was immense. German soldiers in Italy, already facing harsh conditions and dwindling supplies, now had to contend with an enemy who could strike anywhere, any time, and disappear like ghosts. By late 1944, German intelligence assessments of Girka units had evolved significantly from those early dismissive reports.

A document dated November 1944, captured after the war, described Girka battalions as elite mountain infantry, highly motivated, excellently trained in night operations and close combat, should be considered equivalent to German mountain troops in capability. This was high praise. German mountain troops, the gayberg zerger, were among the vermach’s finest soldiers.

To place colonial troops from Nepal in the same category represented a complete reversal of initial assumptions, but the individual German soldiers didn’t need intelligence reports to tell them what they already knew. Hans Vber, who’d survived that night in Tunisia and fought through Sicily and up the Italian peninsula, had his own assessment.

He wrote it in a letter to his brother in December 1944, shortly before being wounded at the Gothic line. We were told these were inferior soldiers, he wrote. We were told they would break easily, that they were only fighting because the British forced them. Every word was a lie. I have fought the Girkas for 2 years now. They are the finest soldiers I have ever faced.

They are small, yes, but they are made of iron. They do not know fear, or if they do, they do not show it. When I see them coming, I know the fighting will be hard. I respect them more than I can say. The respect was earned through specific documented actions that became legendary among German troops. In December 1944, during fighting along the senior river, a Girka rifleman named Panbagta Gurong single-handedly attacked five Japanese bunkers, killing all occupants with his kukri and grenades.

He was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest British military honor. Wait, that was Burma, not Italy. But similar actions occurred throughout the Italian campaign. Girkas repeatedly conducted assaults that seemed suicidal but succeeded through sheer determination and tactical skill. At the Senior River in December 1944, a different action unfolded.

The first battalion sixth Girka rifles attacked German positions in a night assault. The Germans, by now experienced in fighting girkas, had prepared extensive defenses, barbed wire, mines, interlocking fields of fire, illumination flares. The Girkas came anyway. They moved through the wire using Bangalore torpedoes, cleared paths through the minefields, and were on top of the German positions before the defenders could fully respond.

The fighting was brutal, handto hand in some sections. When dawn came, the Germans had been pushed back 500 m. The German commander, assessing his casualties, found that most of his losses had occurred in close combat. The Girkas, once they closed the distance, were devastating. The kukri, which German soldiers had initially dismissed as a primitive weapon, proved terrifyingly effective in the confined spaces of trench warfare.

Lit Ver Schmidt who survived that action later described it to American interrogators after his capture. They are like ghosts. He said you hear nothing, see nothing, and then they are among you. And that knife, that curved knife, it is not just a weapon. It is a symbol. When you see it, you know you are fighting men who have no fear of death.

This absence of fear, or at least its appearance, was perhaps the most unsettling aspect of fighting Girkas. German soldiers were trained to be brave, to face death for the fatherland. But the Girkas seemed to possess a different quality, not recklessness, but a calm acceptance of danger that was almost spiritual.

It came from their culture. Nepal isolated in the Himalayas had maintained independence through military proess for centuries. Gurka men were raised with the expectation that they might become soldiers. It was an honor, a tradition. The British had recruited them since 1815 and over those generations a warrior culture had been refined.

The motto of the Girka regiments was simple. Kafa who knew Maru Ramro better to die than be a coward. German soldiers hearing this translated understood it immediately. It was a sentiment they’d been taught in their own military training. But the Girkas lived it with an intensity that was remarkable even by vermach standards.

As the war in Italy ground toward its conclusion in early 1945, the German army was collapsing. Supplies were gone. Air cover was non-existent. Replacements were old men and boys. The soldiers who remained were exhausted, hungry, and increasingly aware that the war was lost. But even in defeat, even in retreat, German soldiers who’d fought the Girkas remembered them with respect.

In April 1945, as German forces in Italy began their final surrender, thousands of Vermacht soldiers found themselves being processed as prisoners by Allied forces that included Indian divisions. The Girkas who’d fought so fiercely now served as guards and administrators. Oberga frighter Hans Vber wounded at the Gothic line and recovered enough to walk found himself in a P collection point guarded by men from the second battalion 7th Girka rifles.

He recognized their insignia. This was the same battalion he’d first encountered in Tunisia 3 years and a lifetime ago. One of the Girka soldiers, a Havdar sergeant named Dil Bahadur, spoke some German. He’d learned it from prisoners. He approached Weber, who tensed, remembering the night raids, the silent killings, the fear.

Dil Bahadur smiled. “The war is finished,” he said in accented German. “You fought well. Your soldiers were brave.” Weber, surprised, could only nod. We are soldiers. Dil Bahadura continued. We understand soldiers. You did your duty. We did ours. Now it is over. This moment repeated in various forms across hundreds of interactions between German prisoners and Girka guards captured something essential.

The Girkas had never fought with hatred. They’d fought with professionalism, with pride in their craft, with loyalty to their regiment and their comrades. but not with hatred. German soldiers raised in a system that emphasized ideology and racial superiority found this confusing at first.

How could these men whom German propaganda had labeled as inferior fight so well without hatred? How could they be so fierce in battle and so professional in peace? The answer was simple, though it took the Germans time to understand it. The Girkas were professional soldiers in the truest sense. They fought because it was their job, their tradition, their honor.

They fought to win and they fought without mercy when necessary. But they didn’t fight because they hated Germans. They fought because they were warriors and warriors fought. Over 250,000 Girkas served in World War II. They fought in North Africa, Italy, Greece, Burma, Malaya. They earned 10 Victoria Crosses, the highest number awarded to any Commonwealth force relative to size.

They suffered over 32,000 casualties, including 8,985 killed. The German soldiers who fought them never forgot the experience. In the years after the war, as veterans from both sides wrote memoirs and gave interviews, a consistent theme emerged. German soldiers who’d fought the Girkas spoke of them with a respect that bordered on reverence.

Obestin Brunt, who’d interviewed the wounded Girka in Tunisia, survived the war and wrote his memoirs in 1962. An entire chapter was devoted to the Girkas. We were taught that we were the master race, he wrote. We were taught that other peoples were inferior. And then we met the Girkas and we learned that courage and skill and warrior spirit have nothing to do with race or nationality.

They have to do with culture, with training, with tradition. The Girkas had all three in abundance. They were quite simply superb soldiers. I’m honored to have fought against them and grateful that I survived the experience. This sentiment was echoed by countless other German veterans. The initial shock of encountering soldiers who defied all their assumptions.

The growing respect born from repeated combat. The final acceptance that they’d been wrong about so much. Hans Febber, who’d crouched in that foxhole in Tunisia and watched shadows move through the darkness, survived the war, and returned to Germany. He rarely spoke about his experiences as many veterans didn’t. But in 1938, he gave an interview to a local newspaper about his time in North Africa and Italy.

The interviewer asked him which enemy soldiers he’d found most difficult to fight. Weber didn’t hesitate. The Girkas, he said without question, the Girkas. They were small men from mountains I’d never heard of, fighting for an empire that wasn’t theirs. But they were the best soldiers I ever faced. brave, skilled, absolutely fearless.

When I saw them coming, I knew the fighting would be hard. And at night, he paused, remembering. At night, they owned the battlefield. We were just trying to survive until dawn. The interviewer asked if he’d been afraid of them. Weber smiled, a sad smile. “Every soldier is afraid,” he said. “But yes, the girkers terrified us.

Not because they were cruel. They weren’t. They were professional. But they were so good at what they did. And what they did was kill German soldiers. They did it efficiently, quietly, and without hesitation. That’s terrifying. Do you hate them? The interviewer asked. Weber shook his head. No, I respect them.

They were doing their duty as I was doing mine. They were just better at it than we expected. Much better. This respect earned through years of brutal combat became the lasting legacy of the German Girka encounters in World War II. The Germans had begun the war with assumptions about racial superiority and the inferiority of colonial troops.

The Girkas, through their actions in battle after battle, had shattered those assumptions completely. They’d done it not through propaganda or ideology, but through the simplest and most undeniable method possible. They’d proven themselves in combat. They’d fought with skill, courage, and determination that demanded respect, even from enemies who’d been taught not to give it.

The small men from the mountains, no taller than boys, had become giants in the eyes of the German soldiers who’d faced them. Not through size or strength, but through warrior spirit that transcended nationality, race, or empire. In the end, what German soldiers said when they first fought Girkas evolved from dismissive assumptions to shocked surprise to grudging respect to genuine admiration.

The journey from colonial troops to the finest soldiers I ever faced was written in blood across the deserts of North Africa and the mountains of Italy. And in the darkness of countless nights when German centuries stood watch and heard nothing but felt the presence of shadows moving closer, they learned a lesson that no intelligence report could have taught them.

That courage and skill and warrior spirit are not the property of any single nation or race. They belong to those who earned them through training, tradition, and the willingness to face death without flinching. The Girkas had earned them, and the Germans, whatever else they believed, learned to recognize that truth.

News

ch2-ha-How a US Sniper’s ‘Telephone Line Trick’ Killed 96 Germans and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a US Sniper’s ‘Telephone Line Trick’ Killed 96 Germans and Saved His Brothers in Arms January 24th, 1945. Alzas….

ch2-ha-They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs The men behind the wire…

ch2-ha-DEA agents behind hit Netflix show Narcos reveal what they found in ‘neat-freak’ Pablo Escobar’s secret lair as they release new book

In Escobar’s office, the agents found ‘lace negligees and sex toys, including vibrators, all neatly arranged in a closet’. New…

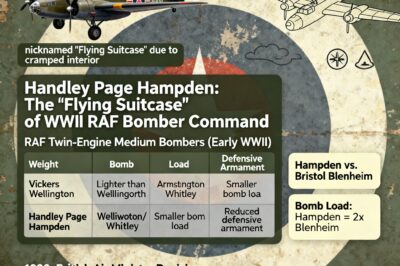

A Bomber So Cramped It Was Called The “Flying Suitcase”

In the first half of the Second World War,RAF Bomber Command relied on three twin-engine medium bombersto carry out its…

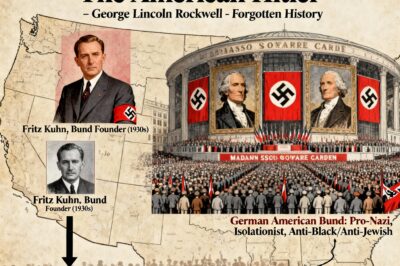

ch2-ha-UNTOLD story of the American Hitler – George Lincoln Rockwell – Forgotten History

UNTOLD story of the American Hitler – George Lincoln Rockwell – Forgotten History Nazism in the United States is nothing…

End of content

No more pages to load