They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

The men behind the wire were not prisoners of war. They were prisoners of their own side. Camp Terawa, Hawaii. January 1944. Morning sun poured across the compound like molten brass. But inside the Briggs perimeter, the air hung thick with sweat and failure. 43 men sat in the dust, scratching at insect bites, staring at nothing.

Some had been there for weeks, others for months. All of them had been written off. These were United States Marines, men who had volunteered to fight, to bleed, to die for their country. Instead, they rotted behind barbed wire on an island paradise, waiting for courts marshall that might never come, or transfers to labor details, where they would spend the rest of the war digging latrines and hauling garbage.

The crimes varied: assault, theft, insubordination. One man had broken a sergeant’s jaw over a card game. Another had stolen a jeep and driven it into the officer’s mess. A third had simply refused to follow an order he considered suicidal and had been right. But being right did not matter when a captain wanted you gone.

The Marine Corps did not know what to do with these men except lock them away and forget they existed. A shadow fell across the gate. The guard looked up from his newspaper, squinting against the glare. A young officer stood at the entrance, 29 years old, maybe 30. uniform clean but not crisp as if he had dressed quickly and without mirrors.

His eyes carried the weight of someone who had seen too much and chosen to say too little. The guard straightened. Help you, sir? I need access to the compound. Purpose of visit? The officer’s gaze drifted past the guard to the men beyond the wire. Broken men, discarded men, men the system had chewed up and spit out. Recruiting, he said. The guard laughed. It was not a kind laugh.

Recruiting from this bunch? He gestured at the prisoners with his chin. Sir, with all due respect, these men are the worst the core has to offer. Brawlers, thieves, troublemakers. You would have better luck recruiting from a carnival. The officer did not smile. Exactly what I need. The guard’s laughter died. He studied the officer’s face for some sign of a joke, found none, and slowly unlocked the gate.

First Lieutenant Frank Toxky stepped into the compound. The change was immediate. Conversations stopped. Heads turned. Men who had been slouching against walls straightened slightly, not from respect, but from weariness. A new officer in the brig usually meant punishment details or transfer to somewhere worse.

Toxy walked slowly down the center of the compound, studying faces. He was looking for something specific, though the men watching him could not have said what. Then one of the prisoners stood. He was older than most, mid-30s, with the weathered face of someone who had spent years under harsh suns. His eyes narrowed as he watched Toxky

approach, and then recognition flickered across his features. Toxky. The man’s voice carried across the compound. I thought they kicked you out of the raiders. Every head turned. The Raiders. The name carried weight even here, even among men who had fallen as far as Marines could fall. The raiders were the elite, the best of the best, handpicked for missions that would make ordinary infantry weep. Toxky stopped walking.

He looked at the man who had spoken, and for a long moment, he said nothing at all. But his eyes answered, “Yes, and that is exactly why I am standing in front of you.” 6 months later, 40 of these forgotten men would land on a beach called Saipan.

The first Japanese homeland island Americans would dare to touch. 30,000 enemy soldiers waiting in bunkers and caves and jungle positions that had been prepared for years. The scout sniper casualty rate in the Pacific ran 73%. Seven out of 10 men who took this job. Their job never came home. Doctrine said they were supposed to observe and report, watch the enemy, map positions, radio coordinates, never engage unless directly threatened. Doctrine was about to be rewritten in blood.

Before we go deeper into this story, I would love to know where in the world are you watching from? Drop your country in the comments. It means more than you know. 6 months earlier on a different island. The lesson had been written in casualties that made generals weep. Terawa atal, November 1943. 76 hours that changed how the Marine Corps thought about amphibious warfare. The plan had been simple.

Land on the beaches, overwhelmed the defenders, secure the island. Intelligence estimated light resistance. The reality was a killing ground. Japanese bunkers had been built with precision that bordered on art. Interlocking fields of fire covered every inch of beach.

Machine gun nests were positioned to catch Marines in crossfire the moment they stepped off their landing craft. And the Americans knew none of it. They walked into the slaughter blind. 994 Marines died in 3 days. Not from lack of courage, not from lack of firepower, from lack of information. They simply did not know what was waiting for them until it was too late.

Colonel James Rizley of the Sixth Marine Regiment stood in the aftermath, looking at casualty lists that seemed to go on forever. Names and ranks and hometowns, each one representing a family that would receive a telegram, a flag, and questions that would never be adequately answered. The pattern was clear to anyone willing to see it.

Men died because they advanced into positions they did not know existed. Artillery could not help because no one knew where to aim. Air support could not help because pilots could not see bunkers hidden under palm frrons and sand. Grizzly did not need more guns. He needed eyes. Eyes that could see what the enemy was hiding.

Eyes that could survive behind enemy lines long enough to send back information that mattered. He needed scouts who were not afraid to work alone. Snipers who could eliminate threats without revealing their positions. men who could think for themselves when radio contact failed and doctrine became meaningless. The Marine Corps had plenty of brave men.

What it lacked were men who could survive in the spaces between the lines where rules did not apply and the only law was staying alive long enough to complete the mission. Rizley knew exactly where to find such men. He had seen them in every unit he had ever commanded.

The ones who got into fights, the ones who bent rules, the ones who ended up in the brig because they could not or would not fit into the rigid structure that the military demanded. The troublemakers, the thieves, the men are too aggressive for polite company. He requested permission to form a specialized scout sniper platoon. When asked who would lead it, he gave a name that made the personnel officer pause.

Frank Toxky, former raider, currently assigned to a training unit after being removed from his previous command under circumstances that remained classified, but had left whispers throughout the core. Too aggressive, unable to follow doctrine, insubordinate, perfect.

Toxy received his orders on a Tuesday morning in early January. By Wednesday afternoon, he was standing at the gate of the Camp Terawa Brig, looking at the men the Marine Corps had given up on. His recruiting method was simple and counterintuitive. When two Marines get into a fight, the winner goes to the brig. Assault charges, dishonorable conduct. Career over. The loser goes to the infirmary.

Victim status. Sympathy. Medical attention. Standard thinking said the winner was the problem. The aggressor. The one who needed to be removed from the unit before he caused more trouble. Toxy thought differently. The winner had proven something. He could handle himself in close combat. He could take a punch and keep fighting.

He had the killer instinct that training could sharpen but never create. Toxky wanted the winners. Over two weeks, he pulled 42 men from brigades and punishment details across the Second Marine Division. The youngest was 17, had lied about his age to enlist, and had been caught stealing from the officer’s mess.

The oldest was 34, a former professional boxer from Philadelphia who had knocked out three military policemen before they finally brought him down. Most had criminal records that predated their military service. Theft, assault, breaking, and entering. One had worked as a bodyguard for a Chicago gangster before deciding that legitimate violence paid better than the criminal kind.

Another had been arrested 11 times before his 18th birthday. The Marine Corps called them troublemakers. The official paperwork labeled them disciplinary problems unsuitable for standard unit assignment. Toxy called them survivors.

Training began in late January at a section of Camp Terawa that had been deliberately isolated from the main base. What happened there stayed there officially and unofficially. The curriculum bore no resemblance to standard marine training. Silent killing came first, not the sanitized version taught in basic, where instructors demonstrated techniques on dummies and moved on to the next topic.

Toxy taught them how to approach a sententury from behind in complete darkness, how to cover a man’s mouth before the knife went in, how to break a neck with a single twist that made almost no sound, how to kill without leaving evidence that killing had occurred. Movement came next. Jungle terrain was unforgiving. A snapped twig could betray a position. A disturbed leaf could reveal a trail.

The men learned to move through dense vegetation like ghosts, leaving nothing behind except the faint impression that something had passed. They studied Japanese, not the language itself, but the documents, how to read enemy maps, how to recognize fortification patterns, how to identify the subtle signs that indicated a bunker entrance or a hidden artillery position.

Marksmanship training focused on the Springfield M1903 rifle fitted with eight power unert scopes. They learned to hit man-sized targets at 600 yards, then 700, then 800. Distance became meaningless when you understood ballistics well enough to compensate for wind, humidity, and the curve of the Earth itself. And then there was the unofficial curriculum.

The United States Marine Corps was the poorest branch of the American military. In 1944, Marines received surplus weapons from the First World War, outdated equipment, inadequate rations. The Army got the new rifles. The Navy got good food. Marines got whatever was left over. To survive, Marines learned to steal. It was not discussed in polite company, but everyone knew it happened.

Supply sergeants kept careful counts because they knew Marines from other units would raid their warehouses given half a chance. Toxky’s men excelled at theft. They raided army supply depots for food that actually tasted like food. They hit Navy warehouses for equipment that actually worked.

They stole jeeps, trucks, and on one memorable occasion, an entire pallet of fresh fruit that had been destined for an admiral’s mess. Other Marines in the sixth regiment noticed. They started calling Toxky’s unit the 40 thieves. The name was meant as an insult. Toxky embraced it. If stealing keeps you alive, he told his men, “I will teach you to steal better than anyone in this theater.

” “They learned to kill without sound, move without trace, and steal without shame.” The Marine Corps taught none of this. Toxy did. But underneath the skills training, a deeper conflict simmered, one that would not surface until they were thousands of miles from Hawaii on beaches that ran red with blood.

Marine Corps doctrine for scout snipers was clear and specific. Observe and report. Identify enemy positions and radio coordinates to artillery units. Do not engage unless directly threatened. Conserve ammunition. Wait for support. The logic seemed sound to officers sitting in headquarters tents moving pins on maps and calculating ammunition expenditures.

Scouts were supposed to be eyes, not hands. Their job was to see and report, not to fight. The statistics told a different story. Scout sniper casualty rates ran 73% in the Pacific theater. Nearly three out of four men who took this assignment never completed their tour. The highest casualty rate of any Marine specialty. The doctrine that was supposed to keep them safe was killing them. The problem was simple.

Doctrine assumed that support would always be available. Radio coordinates and artillery would respond, identify a threat, and someone else would neutralize it. Reality was different. Artillery was often engaged elsewhere. Air support was committed to other targets. Radio frequencies were jammed or overcrowded.

By the time support arrived, the situation had changed. The enemy had moved and the intelligence was worthless. Worse, observe only meant watching fellow Marines walk into kill zones that the scouts had identified but could not warn them about in time. It meant knowing exactly where the machine gun was positioned, but being forbidden to do anything about it except radio coordinates and hope that someone somewhere could respond before more men died. Toxy knew this problem intimately.

He had lived it. The whispers about his departure from the raiders were vague but consistent. Something had happened on a mission. He had spotted a Japanese position. The doctrine said, “Observe and report.” Toxy had attacked instead. He had destroyed the position, killed the crew, saved his entire squad from walking into an ambush that would have cut them to pieces, and he had been punished for it. Insubordination, failure to follow doctrine, too aggressive for the raiders.

The same instincts that had saved lives had ended his career with the elite unit he had worked years to join. Now he stood in front of 40 men who had been punished for similar sins. Men who had broken rules because rules did not fit the situations they faced. men who had chosen action over procedure and paid the price.

He did not recruit them because they were criminals. He recruited them because they were like him. Men did not know how to use it. Men the battlefield desperately needed. By June 1944, the 40 thieves were ready. They knew how to fight, how to hide, how to kill without making noise. They had memorized Japanese fortification patterns and studied aerial photographs until the terrain was burned into their memories. They understood their mission.

Land with the first assault wave, push inland ahead of the main force, locate Japanese positions and radio coordinates, then disappear into the jungle, and keep mapping enemy fortifications days at a time behind enemy lines. No support, no rescue if captured. The intelligence briefings had been clear about what awaited them.

Saipan was the first Japanese territory the Americans would invade that the enemy considered home soil, not occupied territory, not a colonial possession, part of Japan itself. The garrison would defend it with everything they had, including their lives. 30,000 Imperial Army and Navy troops, thousands of armed civilians, an island 14 mi long and 5 mi wide, with Mount Tapucha rising 1500 ft in the center, providing observation posts that overlooked every beach.

concrete pill boxes, interconnected trenches, underground bunkers, every beach and valley registered for artillery and mortar fire. American casualties were expected to exceed 50%. The 40 thieves loaded onto their transport ship with the quiet efficiency of men who understood exactly what they were sailing toward.

Some wrote letters home, others played cards, a few simply stared at the horizon and said nothing at all. Toxky moved among them, checking equipment, answering questions, doing the thousand small tasks that officers did before combat. But his mind was elsewhere. He was thinking about Terawa, about 994 names on casualty lists, about the men who had died because they walked into positions they did not know existed.

He was thinking about the doctrine that said observe and report, about the 73% casualty rate that doctrine produced. He was thinking about the choice he had made with the raiders and the choice he would make again if the situation demanded it. Doctrine be damned. His men were not going to die because some officer in a headquarters tent thought observation was more important than action.

June 15th, 1944, D-Day for Saipan. At 8:44 a.m., First Lieutenant Frank Taxi crouched in a Higgins boat 300 yd from the southern beaches, watching the island grow larger through spray and smoke. The boat bucked and rolled with each wave.

Around him, 40 men pressed together in the cramped space, rifles clutched tight, faces pale beneath their helmets. The smell of diesel fuel mixed with saltwater and the sharp tang of fear. Japanese artillery had found the range. Shells exploded in the surf, sending geysers of water and fragments screaming through the air. Somewhere to the left, another Higgins boat took a direct hit and simply ceased to exist, replaced by smoke and floating debris and things that had been men seconds before. The ramp mechanism groaned. 30 seconds. Someone shouted.

Taxki looked at his men one final time. Strobo with his bazooka. Canupal scanning the beach through binoculars he had stolen from a Navy officer. Hajes checked his rifle with the mechanical precision that had made him the best shot in the platoon. 40 thieves, 40 troublemakers, 40 men the Marine Corps had given up on. They were about to prove everyone wrong. The ramp

dropped into chestde water at 8:47 a.m. Toxy was first out. The water hit him like a cold fist, dragging at his legs, trying to pull him under. Machine gun fire kicked up spray around him, the rounds passing close enough to feel the pressure of their passage. He pushed forward, one step, another. The sandy bottom shifted beneath his boots.

Behind him, his men followed. No hesitation, no panic. They had trained for this moment for 6 months, and now the training took over. The beach was chaotic. Marines fell in the surf, in the sand, at the seaw wall that offered the first real cover. Mortars landed among the assault waves with crumping explosions that threw bodies into the air.

The screams of wounded men mixed with the staccato roar of gunfire. Toxy did not stop at the seaw wall. His orders were clear. Keep moving. Find the Japanese radio positions. Stay alive. The 40 thieves pushed inland. By 9:30 a.m., they had covered 300 yards, farther than any other marine unit on the beach.

They had moved through the first line of Japanese defenses, slipping past positions that were focused on the beach, infiltrating into territory that would remain enemy held for days. They were alone now, 30,000 Japanese soldiers somewhere in the jungle ahead. Night would fall in 9 hours. That was when their real mission would begin. At 10:15 a.m.

, Sergeant Bill Canupal raised his fist, the signal to halt. The platoon froze. 40 men became part of the jungle itself, motionless, invisible. Keniple pointed. Toxky moved forward, staying low, and followed the sergeant’s finger to a ridgeeline 200 yd ahead. The pillbox was perfectly camouflaged. Vegetation covered the concrete roof. The firing slit was angled to be invisible from the beach.

Without Canupal’s eyes, they would have walked right past it. Inside, Toxky could see the barrel of a type 92 Hay heavy machine gun. A weapon capable of firing 500 rounds per minute. Seven men crewed it based on Japanese standard organization.

The pillbox covered all three routes that the Second Marine Division would use to advance through this valley. In 4 hours, when the beach was secured and the main force pushed inland, hundreds of Marines would walk directly into the kill zone. The doctrine was clear. Radio the coordinates. Wait for artillery. Toxy keyed his radio. Command, this is scout one. Enemy position identified. Grid reference follows. The response came back crackling with static. Scout 1 acknowledged.

All artillery assets currently engaged. Earliest support available in 4 hours. Continue reconnaissance. Command out. 4 hours. In 4 hours, the Second Marine Division would be advancing through this valley, straight into the machine gun’s sights. Toxy looked at the pillbox. Then he looked at Strobo and the bazooka slung across his back. Doctrine said, “Wait, observe and report.

Let someone else handle it.” Doctrine had killed 994 men at Turawa. Strobo. The private moved forward. One shot. Make it count. Strobo nodded. He was already unsllinging the bazooka. His movements practiced and precise, he found a position 80 yards from the pillbox. Nelt steadied the weapon on his shoulder. The rocket left the tube with a rushing whoosh at 10:32 a.m.

It covered the distance in less than a second, hitting the firing slit dead center. The explosion was contained by the concrete walls, channeling the blast inward. Seven men died instantly. Before the smoke cleared, the 40 thieves were already moving 300 yd deeper into the jungle.

No trace of their presence except a destroyed pillbox in silence where a machine gun should have been. Four hours later, the second marine division advanced through that valley. They passed the shattered remains of the pillbox without understanding what it meant. No machine gun fire raked their ranks. No ambush cut them down. They never knew why.

By noon, the 40 thieves had mapped 17 Japanese positions, eight machine gun nests, four mortar pits, three artillery observation posts, two ammunition storage areas. Toxy radioed coordinates in encrypted bursts. 20 minutes after each transmission, naval gunfire from destroyers offshore began hitting the targets.

5-in shells demolished fortifications that would have cost dozens of lives to take by infantry assault. This was their mission. Find, mark, disappear, let the big guns do the killing. But the day was far from over. At 3:40 p.m., 2 mi inland, deeper than any American unit would reach for three more days, they found something that made Toxky’s blood run cold.

37 Type 97 medium tanks hidden under camouflage netting in a grove north of Sharon Canoa. Crews lounging in the shade. Officers studying maps. Intelligence had estimated maybe a dozen tanks on the entire island. Intelligence had been wrong by a factor of three. Japanese tank doctrine in the Pacific called for mass attacks at night when American naval gunfire was less effective.

If these 37 tanks hit the beach head after dark, they could potentially break through marine lines, reach the supply areas, destroy the ammunition dumps and fuel stocks that the invasion depended on. Everything they had fought for today could be undone in a single night. Toxy radioed immediately. Command scout 1, enemy armor battalion identified. 37 repeat 37 type 97 tanks. Grid reference follows. Request immediate fire support. The response came back 8 minutes later. Scout one negative on fire support.

Naval gunfire engaged. Supporting units pinned near the beach. Air strikes committed to other targets. Artillery still being unloaded. Earliest support available 4 hours. Continue observation. Command out. 4 hours. By then it would be dark. The tanks would move under cover of night to attack positions.

The opportunity would be gone. Taxki counted his assets. Six bazookas, six rockets per bazooka, 36 rockets total, 37 tanks. The math was almost perfect. He looked at the men around him. Strobo with his bazooka. Hajes, Canupal, the others. 40 men who had been written off by the Marine Corps who had trained for 6 months to do exactly this kind of mission.

40 men against a tank battalion. It violated every tactical principle the core taught. Small units did not attack armor formations. Scout snipers observed and reported. They did not engage unless directly threatened, but Toxky had not recruited me

n who followed principles. He had recruited survivors. At 4:15 p.m., he gave the order to prepare for assault. Six bazooka teams positioned in a semicircle 40 yards apart to maximize coverage. shooters and loaders ready to hit as many tanks as possible in the first 30 seconds before the enemy could respond. The plan was simple. Destroy as many as they could. Withdraw into the jungle. Let the chaos they created by time for reinforcements to arrive.

And then everything changed. At 4:25 p.m., all 37 tank engines roared to life simultaneously. The sound rolled across the grove like thunder. Diesel exhaust mixed with jungle humidity. Tank crews emerged from camouflage dugouts and climbed onto their vehicles. Officers shouted orders. Infantry units began forming up around the tanks.

Not a repositioning movement, preparation for attack. Toxy checked his watch. 4:28 p.m. Sunset was at 7:12. The Japanese were not waiting for full darkness. They were attacking now, hours earlier than intelligence had predicted. The window for surprise assault had slammed shut. Attacking now would accomplish nothing except getting his men killed.

He made the decision in 10 seconds. Stand down. New mission. Shadow and report. We follow them. The tank battalion began moving at 50:07 p.m. Two columns along parallel routes toward the coast. 1,000 infantry alongside moving in the tank’s wake. The 40 thieves followed at 200 yd using jungle cover for concealment.

Every 10 minutes, Toxky radioed updated positions, range to the beach, direction of movement, estimated time of arrival. Somewhere behind them, marine units were repositioning to meet the threat. Bazookas distributed to frontline units, Sherman tanks moving forward, artillery batteries adjusting aim points. At 6:15 p.m., the formation halted. Toxy observed through binoculars from 300 yards.

Officers had gathered for a conference. One pointed toward the coast. Another gestured north. A third unrolled a map and traced something with his finger. The argument lasted 11 minutes. Then the officers returned to their units and the formation changed direction. North, not toward the main beach head. Toxy tracked their new heading and felt his stomach drop. They were not attacking the main beach. They were targeting the gap.

The seam between the second marine division and the fourth marine division. A breakthrough there would split American forces in half. That gap was defended by two marine companies, 340 men against 37 tanks and 1,000 infantry. Toxy had seconds to decide. Attack with six bazookas against 37 tanks or shadow and report. What would you have done? Tell me in the comments.

The radio crackled in his hand. Command needed to know. The entire invasion might depend on what happened in the next few hours. But as he keyed the microphone, Toxky understood something else. This was not a problem that artillery could solve in time. This was not a situation where observation alone would save lives.

340 Marines were about to face annihilation. And somewhere in that column of tanks and infantry rolling toward a gap in the lines that should not exist, was a choice that would define everything the 40 thieves had been created to do. observe and report or become something else entirely. The jungle swallowed the sound of his transmission as the sun began its descent toward the horizon.

In 2 hours, the tanks would reach the gap. In 2 hours, 340 Marines would face the longest night of their lives, and the 40 thieves would discover exactly what they were willing to do when doctrine and survival finally collided. The attack began at 7:23 p.m. Toxy watched from elevated ground as Japanese tanks rolled toward the gap between divisions.

The rumble of diesel engines mixed with the screams of infantry charging behind the armor. Bayonets fixed, voices raised in battle cries that echoed across the twilight jungle. Marine defensive positions erupted with bazooka fire. The first three tanks exploded in rapid succession, their ammunition cooking off in pillars of orange flame.

But 34 more kept coming, grinding forward through the smoke, turrets rotating to find targets. The gap was holding barely. Then Toxky saw something that made his breath stop. One tank had separated from the main formation. It was following a ravine that curved away from the battle, moving fast, heading directly toward a position that should not have been visible from the Japanese lines. Colonel Rizley’s command post. The ravine was a blind spot.

Terrain too difficult for anti-tank weapons. No one had positioned a bazooka there because conventional wisdom said tanks could not use that route. The Japanese commander had found a way. If that tank reached the command post, it would destroy radio equipment, kill senior officers, and paralyze the entire regimental response. The defense would collapse. The gap would fall.

The invasion would be cut in half. Toxky had 90 seconds, maybe less. He did not radio for support. He ran, his hand closed on Herbert Hajes’s shoulder as he passed. The best bazooka shooter in the platoon never missed in training. Hajes did not ask questions. He simply grabbed his weapon and followed.

They covered 200 yd in under a minute, crashing through undergrowth, branches tearing at their uniforms. The tank’s engine growl grew louder with every step. 30 yards from the tank’s projected path, they dropped prone. Hajes shouldered the bazooka, steadied his breathing, waited. The Type 97 emerged from the ravine like a steel beast rising from the earth. Turret rotating, searching for targets.

The commander stood in the open hatch, scanning the darkness with binoculars, completely unaware of the two Marines lying in the vegetation ahead. The tank continued forward 25 yd, 20, 15. Then it stopped. The commander was checking his map, confirming his position before the final approach to the command post.

400 yd away, Colonel Rizley was coordinating the defense of the gap, completely unaware that death was minutes from his door. Hajes fired at 7:32 p.m. The rocket hit the tank’s left side, just below the turret ring where the armor was thinnest. The shaped charge penetrated and detonated inside the crew compartment. The tank died in the fire. 6 seconds later, the ammunition cooked off.

The entire vehicle erupted in a fireball that illuminated the jungle for 300 yards in every direction. Japanese infantry nearby saw the explosion and drew the wrong conclusion. They assumed they had stumbled onto a major marine defensive position. Officers shouted orders. The assault redirected away from the command post toward what they believed was a larger threat.

One bazooka shot had not just destroyed a tank. It had misdirected an entire infantry battalion. Colonel Rizley would never know how close he came to dying that night. The two men who saved him were already running, but the fireball had revealed their position to every Japanese soldier within half a mile.

Machine gun fire rad the area where the shot had originated. Mortar rounds began falling, walking toward the 40 thieves position with mechanical precision. Toxy gave the only order that made sense. Split up. Rally point designated. Move. The platoon dissolved into the darkness, breaking into small teams of four and five men.

Each group taking a different route through the jungle. Standard procedure said, “Stay together.” Reality said together meant dead. Strombos’s team moved north, crawling through undergrowth so thick they could barely see the man in front of them. The sounds of battle faded behind them, replaced by the chirp of insects and the rustle of leaves.

Then voices, Japanese voices. A patrol moving through the jungle with flashlights, searching for the Americans who had killed their tank. Strobo pressed himself into the earth and stopped breathing. The patrol passed within 10 ft, close enough to hear individual footsteps, close enough to smell cigarette smoke on their uniforms.

One soldier stopped directly beside the spot where Strobo lay hidden. The flashlight beam swept across the vegetation inches from his face. The soldier stood there staring into the darkness, listening for sounds that should not be there. 43 seconds. Strobo counted each one. Then the soldier moved on. The patrol continued past. The jungle swallowed their voices.

At 9:00 p.m., 23 men reached the rally point. 17 were missing. Toxky counted faces in the darkness. Strobo, Hajes, Canupal, others, but not everyone. They waited as long as they dared. Then they moved toward marine lines using recognition signals that had been drilled into them during training. Three short whistles, two long challenge and password.

At 9:41 p.m., 23 members of the 40 thieves crossed into friendly territory. 17 were still out there in the dark in enemy territory. Alive or dead, no one knew. Dawn revealed what darkness had hidden. Search teams deployed at 6:30 a.m., retracing the platoon’s route from the previous night.

They found the first body at 70:05. Private Donald Evans, two gunshots to the chest. He had died quickly, probably during the initial withdrawal. His dog tags were missing. The Japanese collected them as trophies. The team marked the location and kept moving. At 8:20 a.m., they found three more. These men had not died in combat.

Their hands were tied behind their backs. They had been bayonetted, wounded, captured, and executed. The Japanese on Saipan rarely took prisoners. They considered surrender dishonorable and extended that contempt to enemy soldiers who fell into their hands. By the end of the day, 34 men were accounted for.

Six confirmed dead, three missing forever, their fates never known. But the mission was not over. At 11:15 a.m. on June 16th, radio contact came from deep behind enemy lines. Five Marines trapped in a cave system one mile inside Japanese territory. One man is burning with malaria fever. Another barely able to walk from dysentery. They could not move without being detected.

Taxki assembled a rescue team personally, six men. They would bring 11 back or none at all. The patrol contact happened at 1:23 p.m. 20 Japanese soldiers moving through the jungle in standard search formation. Too close to hide, too many to avoid. Toxy chose violence. The ambush lasted 7 seconds. L-shaped formation, simultaneous fire.

20 enemy soldiers fell without transmitting a single radio call, but gunfire carries. Japanese units throughout the area heard the shots and began converging. The rescue team ran. At 1:29 p.m., the terrain betrayed them. The path ahead dropped into a ravine 40 ft deep, walls nearly vertical.

Going around would take 15 minutes they did not have. Toxy led them down. At 1:38 p.m., the ravine ended in a box canyon, rock walls on three sides, no exit. Japanese soldiers appeared on the ridges above, rifles aimed downward. 40 at least, with more arriving every minute. 11 Marines, 200 rounds between them. Two men too sick to fight. Then Toxy saw the plants.

Vegetation growing at the base of the rock wall in a box canyon. Nothing should grow at the base of solid stone unless water seeped through somewhere. Unless there was a crack. Two men investigated while the others watched the ridges. They found a narrow opening behind the vegetation, barely wide enough for one man, widening into an upward passage beyond.

The sick went first, then the others, one by one, removed packs and dragged them behind. Complete darkness inside, moving by touch alone. Behind them, Japanese voices echoed in the box canyon, searching for Americans who had vanished into solid rock. At 2:00 7:00 p.m., 11 me

n emerged on the opposite side of the ridge, 400 yd from where they had entered. At 2:23 p.m., all 11 reached marine lines. They had not escaped through firepower. They had escaped through a crack in the rock that the enemy did not know existed. The next morning, Toxky asked for volunteers. The mission was reconnaissance of Garapin, administrative capital of Saipan. Intelligence needed to know whether the Japanese were defending the town or withdrawing to stronger positions. Five men stepped forward.

Strobo, Mullins, Corporal Irazzi, Private Dawn Evans, Toxky made five. They approached from the east at 4:05 p.m. The town had been bombed and shelled into ruins, but Japanese soldiers moved everywhere through the rubble, at least 200 visible, probably hundreds more in the buildings that still stood. At 4:08 p.m., Izzi spotted something that changed everything.

Five Japanese military bicycles leaning against a partially destroyed building. Officer transportation unguarded. The idea was insane. The idea was perfect. Five bicycles, five marines ride through town like Japanese soldiers moving between positions. In the chaos of destroyed Garrapin, five men on bicycles would attract less attention than five me

n on foot trying to hide. At 5:15 p.m., five American Marines began riding through the enemy capital in broad daylight. Japanese troops saw them, waved, shouted greetings in Japanese that the Marines did not understand. The Marines waved back and kept pedalling. For 43 minutes, they rode through Garrapan, mapping positions, counting troops, identifying supply dumps.

They passed within yards of Japanese officers who never suspected that the men on bicycles were enemy reconnaissance. At 5:58 p.m. they completed their circuit and rode out the north end of town one more mile. Then they abandoned the bicycles and disappeared into the jungle. The most dangerous reconnaissance of the Pacific War had been conducted on stolen bicycles in broad daylight.

If you are still watching up to this point, you have walked through the jungle with these men. You have felt the weight of decisions made in seconds. The silence of hiding 10 ft from the enemy. the impossible math of 40 against 30,000. Drop a saluting hand emoji in the comments for the ones who came back and the ones who didn’t. By July 9th, 1944, Saipan was declared secure. The 40 thieves had operated for 3 weeks behind enemy lines.

They had mapped over 200 Japanese positions, called coordinates that destroyed dozens of fortifications, saved a command post from destruction, provided intelligence that changed how Marines fought across the entire island. The cost was written in names that would never grow old, 12 dead, nine wounded, 56% casualties.

Below the 73% average for scout snipers, but still devastating. More than half the unit did not come back whole. Marine commanders estimated their work had reduced overall casualties by 15%. 2,000 men who went home because 40 criminals did what doctrine said was impossible. But the question remained, the question that had hung over Toxky since that morning at the brig.

Why did he understand these men better than anyone else in the core? The answer had been there all along, hidden in the whispers that followed him from the raiders. Toxky had been one of them, the elite, the best. On a reconnaissance mission months before Saipan, he had spotted a Japanese machine gun position that would have cut his squad to pieces.

Doctrine said to observe and report, wait for support. Toxy attacked. He destroyed the position, killed the crew, saved every man in his squad, and he was punished for it. Too aggressive, unable to follow doctrine. The raiders did not need men who thought for themselves when thinking meant breaking rules.

The same instincts that saved lives got him expelled from the unit he had spent years fighting to join. Now those instincts have saved 2,000 more. He had not recruited criminals because they were violent. He had recruited them because they were like him. Men the system could not categorize. Men who broke rules when rules would get people killed.

Men the battlefield desperately needed. The 40 thieves had proven something that would echo through military history for decades. Small groups of unconventional men could accomplish what entire battalions could not. Deep reconnaissance behind enemy lines, independent operation without constant oversight, authority to engage targets rather than simply observe them.

These tactics became the foundation for everything that followed. Navy Seals, Marine Force recon, every special operations unit that came after carried DNA that traced back to a brig in Hawaii and 40 men the Marine Corps had written off. The doctrine changed. Not officially, not immediately, but it changed. The most effective reconnaissance was reconnaissance that could solve the problems it discovered.

The 40 thieves had written that lesson in blood. But the men who survived carried wounds that did not show on medical reports. Most struggled with what would later be called post-traumatic stress disorder. Nightmares that returned night after night. Alcohol that dulled the memories but never erased them.

Jobs that could not hold their attention. Relationships that crumbled under the weight of things they could never explain. The psychological cost of what they had done was never officially recognized or treated. They came home to parades and handshakes and questions they could not answer, then spent the rest of their lives trying to forget what they had seen. The men who had done the most talked the least.

Frank Taxki returned to civilian life after the war. He settled in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, a small town on the Dor Peninsula where the winters were long and the people did not ask too many questions. He became mayor, served his community, raised a family. He never spoke about the war, not to his wife, not to his children, not to anyone.

When people asked about his service, he changed the subject. When reporters came looking for stories, he declined interviews. The medals sat in a box. The memories stayed locked away. 66 years of silence. Frank Taxi died at 2011. His son Joseph found the foot locker while cleaning out his father’s house.

Inside were medals his father had never mentioned. A journal his father had never shared. Photographs of men whose names Joseph had never heard. The story of the 40 thieves had sat in a wooden box under a bed for more than six decades, waiting for someone to open it. Joseph read his father’s words and finally understood the silence.

Some stories are too heavy to carry in conversation. Some memories are too sharp to share with people who were not there. The men who called them criminals were wrong. They were not criminals. They were warriors. And sometimes the men the system gives up on are exactly the men the system needs most. The ones who think for themselves.

The ones who break rules when rules will get people killed. The ones who see what others miss and act before permission arrives. 40 men, 30,000 enemies, three weeks that changed military doctrine forever. They never asked for recognition. Most never received any, but every elite unit that came after them carries their legacy.

The proof that small groups of unconventional men can accomplish what armies cannot. Franksky kept his silence for 66 years. He carried the weight so others would not have to. He watched his men die and his men survive.

And he never said a word about any of it until the day he closed his eyes for the last time. The Foot Locker told the story he never could. And now, finally, the world knows what 40 thieves did on an island called Saipan in the summer of 1944 when doctrine met reality and reality 1. If this story deserves to be remembered, hit that like button, subscribe, and turn on notifications.

We bring back forgotten heroes every week. These men gave everything so others could live. The least we can do is make sure they are never forgotten. Thank you for watching. Thank you for remembering. Today, if you visit the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia, you will find no exhibit dedicated to the 40 thieves. No plaque, no display case.

Their story exists in declassified reports, faded photographs, and the memories of families who only learned the truth after their fathers and grandfathers had passed. Strobo returned to Pennsylvania and worked in a steel mill for 37 years. He never told his wife about the night he lay motionless while a Japanese soldier stood close enough to touch.

She found out from a historian in 2014, 3 years after Strobo died. Hajes became a carpenter in Ohio. The hands that had fired the bazooka shot saving Colonel Grizzly spent four decades building homes for young families. He attended church every Sunday and never once mentioned that he had killed men in the dark.

Canal moved to California and opened a small grocery store. His children thought he had been a supply clerk during the war. The truth came out at his funeral when a marine and dress blues appeared and saluted a flag-draped coffin. These men built lives from the silence they carried. They raised children who never knew.

They grew old with secrets that weighed more than metals ever could. And they never asked for gratitude. They only ask to be remembered.

News

ch2-ha-How a US Sniper’s ‘Telephone Line Trick’ Killed 96 Germans and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a US Sniper’s ‘Telephone Line Trick’ Killed 96 Germans and Saved His Brothers in Arms January 24th, 1945. Alzas….

ch2-ha-What German Soldiers Said When They First Fought Gurkhas

What German Soldiers Said When They First Fought Gurkhas Tunisia, March 1943. The darkness is absolute. Oberrighter Hunts Vber crouches…

ch2-ha-DEA agents behind hit Netflix show Narcos reveal what they found in ‘neat-freak’ Pablo Escobar’s secret lair as they release new book

In Escobar’s office, the agents found ‘lace negligees and sex toys, including vibrators, all neatly arranged in a closet’. New…

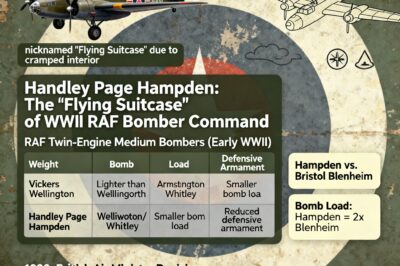

A Bomber So Cramped It Was Called The “Flying Suitcase”

In the first half of the Second World War,RAF Bomber Command relied on three twin-engine medium bombersto carry out its…

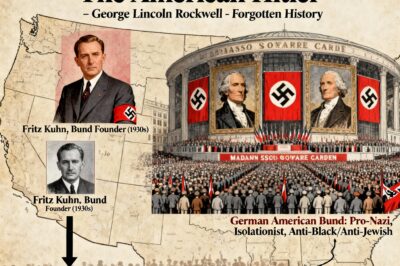

ch2-ha-UNTOLD story of the American Hitler – George Lincoln Rockwell – Forgotten History

UNTOLD story of the American Hitler – George Lincoln Rockwell – Forgotten History Nazism in the United States is nothing…

End of content

No more pages to load