December 19, 1944 – German Generals Estimated 2 Weeks – And Lost The Ardennes In Just 2 Days

The cold had a weight to it. Outside Eisenhower’s headquarters at Verdun, the air itself seemed brittle, sharp enough to cut. Every breath carried the scent of wet wool, diesel, and cigarettes. Inside, maps cover every wall, covered again with pencil lines and coffee rings, where generals had been arguing for days about a war they thought was nearly over. The door opened and Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr.

stepped inside. His boots clicked once on the stone floor before the sound was swallowed by the quiet. Around the table, the men of Eisenhower’s staff looked up from the maps, tired, pale, and holloweyed. They had been awake for 3 days watching reports come in from the Ardens. Reports that made no sense.

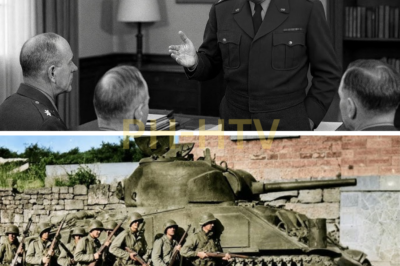

250,000 Germans, a thousand tanks, entire American divisions missing. Communications shattered. A front that had looked unbreakable, suddenly bleeding at every point. Eisenhower, standing at the head of the table, looked older than his 54 years. How long, he asked, would it take you to turn your army north? Patton didn’t blink. 48 hours.

Silence. Somewhere a pencil snapped. One of the staff officers, an engineer colonel with frost still on his shoulders, let out a short laugh that died in his throat. 48 hours to turn an entire army, to pull six combat divisions out of the line, turn them 90°, march them 100 miles through a blizzard, and attack. It wasn’t merely unlikely.

It was insane. But Patton wasn’t guessing. He wasn’t bluffing. What no one else in that room knew was that he’d already planned it weeks earlier. Three separate contingency plans drafted quietly without orders, complete with routes, supply allocations, and pre-written movement orders.

While others reacted, Patton had already rehearsed the impossible. That moment, the stunned silence, the disbelief marked the turning point of the last great German offensive in the West. This is how the man the Allies distrusted most and the Germans feared most turned what should have been a logistical nightmare into a masterclass in foresight and execution and in doing so ended Hitler’s last hope of victory. Patton was 59 years old.

He had been waiting for this war his entire life. Every decision, every obsession, from reading Caesar’s commentaries as a boy to memorizing Napoleon’s campaign roots was building toward one moment to lead an army in the greatest war of his generation. And by late 1,944, he could feel that ched slipping away.

He’d been brilliant in North Africa, relentless in Sicily, but controversy had shadowed him like a curse. The slapping incidents, the newspaper scandal, Eisenhower’s near dismissal, all had left scars. For months, he’d been a decoy, commanding a fake army made of rubber tanks and radioatic to fool the Germans into expecting an invasion at Calala.

Now, finally, he had the third army. 250,000 men, hundreds of tanks, and one of the best staffs in Europe. But the advance into Lraine had stalled. Mud, mines, and the fortress city of Mets had turned his lightning war into a slow motion grind. Supplies were short, morale was strained, and Patton knew what people whispered. He’s only good when the enemy runs.

He needed redemption. A victory so decisive it would erase every doubt. That’s why when his intelligence chief, Colonel Oscar Ko came to him in early December. Patton didn’t dismiss the warning. Ko’s analysts had noticed something strange. Gaps in German radio traffic, missing divisions, coded signals from the Eiffel. It didn’t look like retreat. It looked like concentration.

They’re planning something, Ko said. Probably in the Ardens. Patton stared at the map. The Ardens, thick forest, narrow roads, considered impassible in winter. The Allies had left it lightly defended because Logic said no armored army could move through it. But logic wasn’t something Hitler respected anymore. Patton gave the order quietly. Draft three plans.

one for a 90deree turn north with three divisions, one with four, one with six. No one else in Europe was thinking about an offensive there. Patton didn’t ask permission. He didn’t tell Eisenhower. He just prepared. When the German attack came at dawn on December 16th, the world shifted overnight. Fog rolled in thick over the Ardans, muffling the roar of engines.

Then without warning, thousands of artillery guns opened fire. Entire towns vanished under explosions. American lines stretched thin, shattered. Radioetss went dark. The Germans, the same army everyone had called finished, surged forward behind panthers, tigers, and screaming halftracks painted white for snow camouflage.

Three days later in Verdon, Eisenhower called his generals. The reports were catastrophic. The Germans had broken through everywhere. Patton listened, hands clasped behind his back, expression unreadable. When Eisenhower asked for options, the room hesitated. Bradley’s first army was in chaos. Montgomery was calling for a deliberate defense. No one knew how to respond.

Then Patton said, “I can attack north in 48 hours with three divisions.” The logistics men almost laughed. Turning an army wasn’t like turning a steering wheel. It meant uprooting 250,000 men actively engaged in combat. Moving them 100 miles across frozen France through jammed roads and then launching an offensive.

Each division had thousands of vehicles, each dependent on fuel, ammunition, maintenance, and coordination. Every bridge, every choke point had to be recalculated. In modern terms, it would be like rerouting a metropolis overnight, except that the city was armed, freezing, and being shot at. But Patton’s staff had already divided the work. General Hobart Gay, his chief of staff, broke down the movement into three synchronized corridors.

Engineers scouted road capacity and traffic control points. The Red Ball Express, the legendary supply convoy system that had kept Allied armor moving since Normandy, was redirected north instantly. Fuel dumps were created overnight out of thin air. orders were radioed using pre-coded phrases that gave nothing away to German intercepts.

By midnight, December 19th, as German generals celebrated their breakthrough, Patton’s third army was already rolling. And this, the part most histories mention only briefly, was where Patton’s genius wasn’t just aggression. It was administrative warfare.

He understood that modern war wasn’t decided only by courage, but by movement. A good plan, violently executed now, is better than a perfect plan next week. He’d written years earlier. This wasn’t rhetoric. It was doctrine. Every man in his army knew the pattern. When orders came, there was no discussion. Convoys moved. Mechanics worked through the night.

Tank crews slept in their Shermans. Engines idling so oil wouldn’t freeze. Fuel trucks leapfrogged forward, guided by headlights covered in slits of paper to prevent aerial spotting. It was a ballet of steel and discipline performed in pitch darkness and subzero cold. By December 21st, the fourth armored division was already 60 mi north.

Engines still warm from their previous fight near Sarbuken. In 2 days, they had done what the German high command insisted was physically impossible. The Wormact had counted on time at least 2 weeks before any American counterattack. What they got was Patton in motion before they’d even finished celebrating. The real miracle wasn’t speed.

It was synchronization. American logistics at that moment were operating at the peak of wartime innovation. The Red Ball Express, an army within the army, moved over 12,000 tons of supplies a day, a feat unmatched by any power before or since. Most of its drivers were African-Amean soldiers operating under brutal winter conditions with almost no rest.

Their contribution, often ignored, made the Third Army’s turnaround possible. Patton knew it, too. “My men can fight only because those boys can drive,” he told reporters later. Behind them came the mobile repair units, maintenance trucks equipped with welding gear, spare treads, and engines. Patton’s doctrine was simple. Replace, don’t repair.

German armor was elite, but brittle. A broken Tiger stayed broken. American armor was mediocre, but endless. Every time a Sherman threw a track, another was pulled forward. It wasn’t romantic, but it was decisive. On the German side, Field Marshal von Runstead’s staff believed they were dealing with an exhausted Allied army trapped by weather and fuel shortages.

They had no idea that American industrial capacity had turned logistics into a weapon. They had designed their offensive around captured fuel, an assumption that turned into catastrophe. By the time confr Piper Tiger 2oss reached Stavallet, they were already running dry. By contrast, Patton’s convoys were swimming in fuel.

His supply officers even dumped gasoline into empty beer bottles for emergencies, a bizarre but real practice in the Ardan winter. As the Third Army rolled north, Patton prayed for one more miracle. Clear skies, December 22nd, 1944. Dawn never really came that day. The sky was a sheet of iron.

Snow fell sideways, driven by wind so fierce it stripped the paint off trucks. The temperature hovered near zero, the kind of cold that makes steel brittle and skin tear at a touch. Somewhere north of Arlon, the fourth armored division’s lead tanks crawled along a narrow, icelick road. Their engines roared in agony. oil thick as tar, gears grinding.

The men inside those Shermans could barely feel their hands. Frost crept over Goggles. Breath froze in seconds. But they kept moving. They had orders. And those hoarders came from a man who had promised the impossible. Patton’s third army was now attacking north uphill through frozen forest against the flank of the most dangerous German offensive since 1,940.

And behind every mile was a staggering orchestration of willpower and engineering. The fourth armored division, the same unit that had liberated Nancy, was spearheading the push toward Baston. Its mission reach the 101st Airborne Division encircled for six days in that small Belgian crossroads town.

The men of the 101st were surrounded, freezing, outnumbered, running out of ammunition and morphine. The Germans had offered surrender. Their answer had been one word, nuts. But defiance doesn’t keep men alive. They needed rescue. Patton’s men were that rescue. The first day’s advance covered barely seven miles.

Snow drifts made tank movement unpredictable. Engines overrevd. Tracks spun uselessly. Entire platoon halted just to winch a single vehicle free. Every hill became a choke point. Every village a miniature fortress. The Germans were masters of defense by then. Camp Groupen mixed units of armor, infantry, and anti-tank guns, ambushed from tree lines, withdrew, then struck again.

The 37th tank battalion fought through the villages of Martellange and Warneck. Each street, a death trap of frozen rubble. German 88 mm guns, the most feared weapon of the war, punched through Shermans as if they were paper. Yet the Shermans kept coming. Patton’s doctrine was relentless momentum.

If one tank was destroyed, two more advanced. He once told his officers, “A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan next week.” Those weren’t words anymore. They were the rhythm of that advance. Behind the tanks came the infantry, frostbitten, exhausted, caked in mud and ice. Some had wrapped burlap sacks around their boots.

Others stuffed newspapers under their coats to block the wind. They marched with blackened faces and cracked hands, rifles slung low, bayonets fixed, eyes hollow. Many hadn’t slept properly in three days. They didn’t complain. They didn’t have time. What they faced wasn’t just the German army. It was the environment itself. A living hostile force. German vehicles running on synthetic oil derived from coal.

Seized up in the cold, their panthers and Tiger twos, engineering marvels on paper were mechanical coffins when temperatures dropped. One German commander later wrote, “We could hear the Americans moving while our tanks stood like frozen monuments.” Patton’s army, by contrast, was fueled by relentless improvisation.

Mechanics thawed engines with blowtorrches. Cooks brewed coffee in oil drums. Medics cut morphine vials with bare bleeding fingers. The Red Ball Express supply trucks driven mostly by black soldiers who rarely got medals or recognition thundered up behind the armored columns, headlights hooded, tires chained, engines screaming under loads of ammunition and gas.

Every day they kept the lifeline alive. Without them there would have been no counterattack, no baston, no victory. By the night of December 23rd, Patton faced a new enemy. The weather, a solid blanket of cloud, had grounded Allied aircraft for a week. Reconnaissance was impossible. The Luftwaffa, though weakened, still prowled the skies when visibility cleared, but for the most part, Ulf armies fought blind.

At his headquarters in Luxembourg, Patton summoned his chaplain, Colonel James O’Neal. The story has been told so many times it sounds apocryphal, but it happened. Patton said, “Chaplain, I want you to write me a prayer for good weather, for killing Germans.” O’Neal hesitated. He’d never been asked to write an operational prayer, but he did.

Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech thee of thy great goodness to restrain these immodderate reigns with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon thee, that armed with thy power, we may advance from victory to victory.

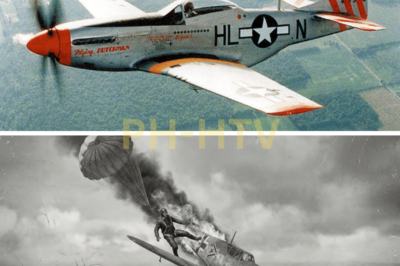

Patton had 250,000 printed copies distributed to every man in the Third Army. On the back, he wrote a Christmas greeting thanking them for their valor. The next day, December 24th, the skies opened. The clouds broke apart like torn fabric. Blue light flooded the snow fields. For the first time in a week, Allied planes roared overhead. Fighter bombers, P47 Thunderbolts, and Typhoons swooped low over the forest roads, strafing German convoys, blasting columns trapped in choke points.

The Luftwaffa tried to respond, but was shredded by superior numbers and radar coordination. That moment changed everything. The Germans had counted on bad weather to protect their advance. Instead, they were caught in the open, burning. Patton called it the greatest Christmas present the Third Army ever received.

In Baston, the 101st Airborne was down to their last rounds of ammunition. They’d been eating snow for water, sleeping in foxholes half filled with ice. Every night, German artillery rained down. Men dug themselves deeper, not for cover, but to find warmth. Then at 4:50 p.m. on December 26th, a Sherman tank from Lieutenant Charles Bod’s platoon rolled up a narrow road and stopped in front of an astonished paratrooper.

The tank commander yelled, “Hey, you guys are from the 101st, right?” The paratrooper nodded, eyes wide. “Then you can tell the bastards we’re here, the fourth armored.” The corridor was barely 500 yd wide. A thin snow choked artery linking Baston to the outside world. But it was enough. Supplies began flowing in. Wounded began flowing out.

The siege was broken. And with that, the Battle of the Bulge turned. Most histories stop there. But the real story, the one most people don’t tell, is what came after. The Germans had thrown everything into this offensive. It was their last roll of the dice.

Over 2,400 tanks, many of them the last operational armor reserves in the west. They had hoped to split the Allied front, capture Antwerp, and force a negotiated peace. Instead, they found themselves strangled by their own ambition. Every mile they advanced lengthened their supply lines. Every destroyed fuel depot meant one less tank moving forward.

Conf group Piper, the SS spearhead meant to lead the breakthrough, ended up abandoning its tanks and retreating on foot. Out of fuel, out of time. Patton’s attack didn’t just relieve Baston, it reversed the entire offensive. His movement north forced the Germans to divert reserves meant for the Muse River crossings.

By January, a bulge was shrinking. The psychological toll on the Germans was enormous. They’d believed the Americans were too slow, too soft, too bureaucratic to react quickly. What they faced instead was a military machine capable of turning an entire front in less than 3 days. General Gunther Blumenrit, one of the German planners, later said, “We regarded General Patton extremely highly as the most modern commander on the battlefield.

” We expected at least 2 weeks before his army could react. He did it in 2 days. This was extraordinary. It wasn’t luck. It wasn’t improvisation. It was preparation meeting opportunity. Patton had trained his army like a living organism, decentralized command, initiative at every level, logistics as aggression. He didn’t believe in static defense. To him, the best defense was movement, violence, and speed.

And when the war handed him chaos, he used it. When the smoke finally cleared in January 1945, the numbers told the story. Over 100,000 German casualties, more than 700 tanks destroyed or abandoned. The Luftwaffa effectively broken. The Western Front, once teetering, stabilized. The German army never recovered. The Bulge had consumed their last operational reserves.

When the Soviets launched their massive winter offensive on January 12th, 1945, there were no divisions left to transfer west. The Reich was finished. And at the center of it all was Patton, the man who had turned the impossible into execution, who had done in 72 hours what military orthodoxy said required weeks.

When the guns finally fell silent across the Ardens, the forests were filled with ghosts, both living and dead. Burned out tanks lay half buried in the snow, their metal twisted by heat, tracks snapped like bones. American soldiers moved carefully among them, stepping over frozen bodies, faces pale under the winter sun.

The smell of fuel, cordite, and decay clung to the air. Patton arrived days later, riding in a command car, his polished helmet gleaming despite the grime around him. His staff said he looked almost serene, as if the violence had finally confirmed what he’d always believed, that destiny had been waiting for him to prove himself.

But for the men who fought under him, it wasn’t destiny. It was exhaustion. The soldiers of the Third Army had driven themselves past human limits. Marching, fighting, digging, freezing. Many didn’t remember Christmas at all, except for the thunder of artillery and the distant smell of burning pine. They’d seen friends die from shrapnel, from sniper fire, from exposure.

For them, Patton’s miracle wasn’t divine intervention. It was the sheer will not to collapse before the man next to you did. Even victory had a cost. Military historians would later call Patton’s 90° turn a masterpiece of logistics, but few mention what that meant in human terms. Truck drivers who slept only in 20inut bursts.

Engineers who built and rebuilt bridges through nights colder than death. Medics who dragged the wounded through snow fields under mortar fire. Chaplain reading last rights in frozen foxholes while tanks clanked past toward another village with another German ambush waiting. When Patton wrote in his diary, “It’s really quite simple when you know what you’re doing.” It wasn’t arrogance.

It was revelation to him. War was mathematics, movement, and faith combined. Everything was preparation for the moment when hesitation meant death. After the war, the interrogations began. Captured German officers, veterans of every front, were asked a simple question. Which Allied commander did you fear most? Over and over, they gave the same answer. Patton.

General Gunter Blumenrit explained, “We feared his speed. We feared his nerve. He was the only Allied commander we could not predict. The irony was brutal. The allies had spent years doubting him. His own country had nearly ended his career after the Sicily incident. He’d been sidelined, mocked by newspapers, despised by some superiors.

Yet when the moment of crisis came, he was the only general in Europe who had a plan already in motion. That paradox, the man hated by bureaucrats but revered by enemies, became Patton’s curse and his immortality. He was the last of an older breed of warrior, romantic, superstitious, obsessed with destiny.

He read Caesar and Napoleon, quoted the Bible, and carried a revolver with ivory grips engraved with his initials. To his men, he was both inspiring and terrifying. He could quote poetry one minute and order a frontal assault the next. He believed in reincarnation, that he’d fought at Carthage and Waterloo.

To him, the battlefield wasn’t just geography. It was the stage of eternity, and he was its actor. But beneath the myth, there was method. A kind of ruthless practicality that defined modern warfare. What made the Third Army’s turn north possible wasn’t divine guidance. It was systems, decentralized logistics, flexible command structures, communication networks that treated every radio operator as an extension of command, not a messenger.

the red ball express supply chain that never stopped rolling. Even when the front changed direction, the Germans, trapped in an older model of centralized control, simply couldn’t match it. Hitler’s obsession with micromanagement paralyzed his commanders. Orders had to be approved through layers of hierarchy. Fuel convoys had to wait for permissions that never came.

By the time decisions reached the front, the situation had already changed. Patton’s genius wasn’t only speed, it was trust. He trusted his subordinates to act, not wait. He built a culture of initiative where sergeants could improvise and lieutenants could lead. He said, “Never tell people how to do things.

Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity. That ethos, command intent, decentralized execution became the foundation of post-war US military doctrine. The concept still shapes how modern militaries fight today. When NATO was formed, Patton’s war diaries were required reading for staff officers.

His 48-hour attack became a case study in operational art, the link between tactics and strategy. His success wasn’t about ego. It was about system design. The Third Army was a prototype for how wars would be fought for the next century. But history has a cruel sense of timing. The war patent was born for ended too soon for him. In May 1945, Germany surrendered. The guns went silent.

For the first time in his life, Patton had no enemy left to fight. He was restless, irritable, almost lost. The adrenaline that had driven him for years now had nowhere to go. His speeches became darker, his opinions more controversial. He warned of Soviet expansion, calling the Red Army the next enemy.

In some ways, he saw the Cold War before it began. In December 1945, just months after victory, he was injured in a car accident near Mannheim. A broken neck left him paralyzed. 12 days later, he died in his sleep. He was 60 years old. His final words were simple. This is a hell of a way to die. He was buried among his men at the American cemetery in Ham Luxembourg, the same soil where he’d once directed the relief of Baston. Even in death, he refused to leave his soldiers behind.

Today, when militarymies teach about the Battle of the Bulge, they emphasize coordination, timing, logistics, but those are abstractions. What Patton proved wasn’t just that planning matters. It’s that belief matters. Not faith in miracles. Faith in preparation. Faith that when everything collapses, someone somewhere has already thought of this exact moment and built the road map out.

That’s why when Eisenhower asked how long it would take him to turn his army north, Patton didn’t pause, didn’t look at his maps, didn’t consult his staff, he just said 48 hours because he’d already written the orders because he had already rehearsed the impossible because he understood that courage without preparation is chaos, but preparation without courage is useless. When German generals were asked what finally broke them in the West, they didn’t talk about numbers or machines.

They talked about momentum. They said the Americans kept coming faster, stronger, more flexible than their intelligence had predicted. They said their own tanks froze, their radios jammed, their lines broke under relentless pressure. They said Patton’s army moved like a storm.

Winston Churchill later said, “This was undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever famous American victory.” He was right. But not because of scale, because of what it represented. The Battle of the Bulge wasn’t a fight for ground. It was a fight for tempo, for initiative, for the right to decide the future.

And Patton’s 48-hour miracle proved something timeless. That even in war, perhaps especially in war, the future belongs to those who prepare when others only react. The German high command laughed when he said 48 hours. They stopped laughing when his tanks arrived. They laughed again when he prayed for good weather. They stopped laughing when the clouds broke. They laughed when he said he’d kill them in the Ardens.

And then they stopped laughing forever. Snow falls quietly over the Ardens. Now, the forests have grown back. The burned out tanks are gone, replaced by memorials and silence. But under that silence lies the same ground where men once froze, fought, and died for inches of earth and hours of time.

Somewhere beneath that soil, traces of Patton’s roads still exist. The paths where his convoys rolled, the frozen fields where his men waited for orders that changed the course of history. And if you stand there long enough in the stillness of winter, you can almost hear it. The distant rumble of engines, the voice of a general saying, “Attack! Attack! Attack!” Because in the end, Patton’s legacy wasn’t about tanks or tactics. It was about motion.

The refusal to stop when stopping meant death. He turned the impossible into a direction on a map and the direction into victory. And maybe that’s why his story still matters because it reminds us that preparation is destiny waiting for its moment. That when everyone else freezes, you move.

that when others say impossible, you say 48 hours. If you’ve made it this far, take a moment to reflect on what 48 hours really means. Not just in war, but in life. It’s the space between hesitation and action, between doubt and momentum. Because whether it’s a battlefield or your own struggle, history doesn’t remember the ones who waited. It remembers the ones who moved.

News

ch2-ha-This “Kid” WRECKED Hitler’s Most FEARED SS Panzer Brigade!

This “Kid” WRECKED Hitler’s Most FEARED SS Panzer Brigade! Thursday, December 21st, 1944. Days after murdering 85 American PS, the…

A STREET GIRL begs: “Bury MY SISTER”, the UNDERCOVER MILLIONAIRE WIDOWER’S RESPONSE will shock you

A STREET GIRL begs: “Bury MY SISTER”, the UNDERCOVER MILLIONAIRE WIDOWER’S RESPONSE will shock you Sir, can you…

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Really Said When Patton Reached Bastogne Ahead of Everyone

What Eisenhower Really Said When Patton Reached Bastogne Ahead of Everyone December 1944 arrived over Western Europe with a cold…

ch2-ha-German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds

German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds March 15, 1944,…

ch2-ha-By 1942, the Japanese Empire stood at the height of its power, controlling most of Southeast Asia and dreaming of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” But just three years later, everything collapsed.

World War II from Japan’s Perspective – Why Did Japan Lose? By 1942, the Japanese Empire controlled most of…

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours In the closing winter of 1944,…

End of content

No more pages to load