“Please… My Children Are Starving” – German Mother’s Begging Shocked the American Soldier

March 1946. The American sector of Berlin lies silent under a new layer of snow, soft white on top of black ruins. The air smells of wet ash and coal smoke while thin children dig in the rubble for potato peels and burned bread. Germany has surrendered 11 months ago, but for a young mother named Anna Schaefer, the real war now is against hunger, not bullets.

Her radio has sworn that American soldiers are monsters who will steal, hurt, and shame her. Yet the man she walks toward carries a rifle on his shoulder and a bar of chocolate in his pocket. He comes from a country overflowing with meat, coffee, and sugar.

She comes from a city where bread is cut with sawdust, and hope is given out in crumbs. In a world that has just learned how to burn cities from the sky, one quiet choice on this snowy corner will weigh more than all his ammunition and reach all the way to a grave in Brooklyn. This wasn’t propaganda. It was reality. And it turned sworn enemies into family across three generations.

If stories like this move you, please subscribe, like this video, and stay with me to the very end so we can keep these forgotten memories alive. March 1946. Berlin lay under a hard gray sky, its broken streets dusted with new snow that could not hide the ruins. Half the buildings were smashed open, rooms hanging in the air like broken dollhouses.

The smell of wet ash, cold smoke, and rotting garbage mixed with the sharp clean bite of winter. Somewhere a loose shutter banged in the wind. Somewhere a baby cried, then went quiet again. Germany had signed surrender papers 11 months earlier, but for people in Berlin, the war had not ended. It had only changed shape. The bombs had stopped falling. Hunger had taken their place.

Official food rations in the city dropped to around 1,000 calories a day, barely half what an adult needed to stay healthy. Many got less. A Berlin doctor later wrote, “We do not treat sickness anymore. We treat starvation in different forms. In one damaged street of the American sector, walked a woman named Anna Schaefer, 28 years old. Her shoes had holes in the soles stuffed with paper.

Her coat was too thin for the bitter air. On her hip, she carried her four-year-old son, Klouse. His legs were like sticks under his wool stockings. With her free hand, she held her six-year-old daughter, Lizel, who stared at the snow as if she wanted to eat it. The three of them had not eaten a real meal in weeks.

Most days they shared a single boiled potato, sometimes stretched with turnip or a thin soup of cabbage leaves. Anna had not eaten at all for 3 days, so the children could have her share. Her head rang when she walked. Her hands shook from cold and from the emptiness in her belly. In her pocket were three ration cards and nothing left to buy.

Every step she heard the same voice in her memory. The voice of the Nazi radio that had shouted through the war. It had called the Americans monsters, called them frinder, and Jew lovers said they would burn, steal, and shame every German woman. Neighbors still whispered stories of robbery and revenge.

To many, like Anna, the enemy wore a round steel helmet and carried a gun and an unknown language. Yet as she came around a corner past a burnedout tram and a frozen fountain full of ice and bricks, she saw one of those enemies standing alone. An American soldier tall in his heavy wool coat helmet pushed back a little on his head. A rifle hung from his shoulder. A pair of dog tags flashed silver at his neck when he turned.

He was 22 years old with a boy’s face under the chin strap. His name was Private First Class James O’ Connor from Brooklyn, New York. In his mouth, he rolled a piece of Wrigley’s chewing gum. In his pocket, he carried something that almost no German child had seen since before the war. Chocolate.

He drew a long breath and tasted coffee on the back of his tongue from the mess tent breakfast. An American soldier in 1945 got about 3,800 calories a day in rations, almost four times what many Berliners were living on. Anna watched him from the shadow of a doorway. She could smell him even from there. Soap, tobacco, the faint animal warmth of wool that had been dry all winter.

He looked bored, not cruel. He kicked at a chunk of rubble and watched it slide over the ice. For a moment he seemed like just another young man far from home. Then he shifted his rifle and she remembered every warning she had ever heard. She looked down at her children. Klaus’s lips had a blue line.

Lazel’s fingers were thin as matchsticks inside her mittens. Their eyes were too big for their faces. They were past hunger now and moving into something worse, a slow fading. Anna knew that if she did nothing, one of them might not live to see the spring. A Berlin mother later wrote in her diary, “We were told the Americans would drink our blood. In truth, we only wished they would give us their bread.

” Anna felt that same terrible paradox in her chest. “The only people in Berlin who still clearly had food were the men she had been told to fear the most. She swallowed hard. Pride shouted at her to turn away. Fear told her to hide.” Another voice, quieter but stronger, said, “If I do nothing, my children will die.” She stepped out from the doorway into the open street into the falling snow.

Each step toward the soldier felt like walking off the edge of a roof. Bitter, she called, her voice rough from cold and hunger. Then again, louder. Bitter. The word was small against the winter air. James heard it and stopped chewing. He turned and saw a thin woman with two children clinging to her in the ruins of his enemy’s capital.

For a heartbeat, two worlds faced each other. The victor with a full stomach and a rifle. The defeated mother with empty hands and empty children. This wasn’t propaganda, but it was reality. And it cut through every story both sides had been told. Anna forced the English words from her memory learned at school before the war. “Please,” she said, her voice breaking.

“My children are hungry. Do you have anything?” She waited for the shout, the insult, the raised gun. Instead, James O’ Connor slowly reached into the pocket of his field jacket. What he drew out of that pocket would not match anything Anna had been taught to expect, and it would lead her family toward a very different kind of future.

James’s hand came out of his pocket, holding a brown paper bar with a silver edge, a Hershey chocolate, then another, then a small round tin with English words on the side. spam. The smell of meat and fat came out when he tapped the lid with his thumb. In his other hand, he still held his rifle, but now it hung loose, almost forgotten. Anna stared.

Her mind could not join the picture. An American helmet, an American gun, an American chocolate held out toward her children. Behind her, Lizel pressed her face into her mother’s coat. Klouse just stared at the bar as if it were a toy from another life. here,” James said softly in English, then slower.

“For kinder,” he pointed to the children. His voice had the flat sound of Brooklyn streets, hard and friendly at the same time. The children did not move. All their lives, they had been told, “Never take anything from the enemy. Never trust them.” Anna felt tears burn in her cold eyes. The wind bit her cheeks. The snow fell thicker now, making the street even quieter. She bent her head close to Lizel’s ear.

“His goo,” she whispered. “It’s all right. Take it.” The girl looked up at the strange soldier. Her small hand shook. James saw her fear. Slowly, he peeled back the paper on one bar himself, broke off a square, and put it in his own mouth. He chewed, then grinned, showing her the half-melted chocolate on his tongue like a silly trick.

“See,” he said. Y. The smell hit them first. Rich, sweet, almost impossible. At last, Lizel reached out quick as a bird, took the bar, and held it tight. Klouse grabbed at the second one. They bit in, eyes wide. Later, Anna would say, “It was like watching color come back into a black and white picture.

” James was not done. He pushed the tin of spam into Anna’s hands, then a pack of Wrigley’s gum. She felt the hard weight of the meat, heavier than anything she had carried in weeks. It seemed wrong that one tin could feel like hope. Then he looked up and down the empty street as if checking for someone. “Come,” he said, waving his hand toward the end of the block. “Food.” He pointed to his mouth, then down the road.

His face asked a question. “Do you trust me?” Here was the sharpest paradox of all. The only person in Berlin willing and able to feed her children was a man in the uniform she had been taught to hate. For a moment, Anna could not move. A German woman later wrote, “We stepped toward the people we had called devils because hunger is stronger than fear.

At last,” Anna nodded. “Yeah,” she said. “We come.” They walked 10 minutes through the ruins, past burned out trucks and walls full of bullet holes. The snow squeaked under their thin shoes. Finally, low tents appeared. Ropes stiff with frost. From inside came a smell that almost made Anna dizzy. Coffee, fried fat, baking bread.

It was the American mess. Around 50,000 US troops would pass through Berlin in the occupation years, and every one of them ate from kitchens like this, drawing roughly 3,800 calories a day in meat, bread, sugar, and coffee. Outside, German civilians sometimes survived on a quarter of that. James led them in. Warmth hit their faces.

A few soldiers looked up, surprised to see a German woman and two children. A cook sergeant with a stained apron listened as James spoke fast English. The man shrugged once, then got to work. Minutes later, he set a metal tray on a table, thick slices of dark rye bread, a bright square of butter on each plate, two fried eggs per person, mugs of warm pale milk made from powder, and a bowl of canned peaches in heavy golden syrup.

The steam rose in soft curls. Anna stood frozen. She had not seen so much food in one place since 1941. Her legs went weak. James pulled out a chair for her, then for the children like a waiter in a small cafe back home. Klouse climbed up and began to eat with both hands. Yolk running down his chin.

Lazel tried to use her fork, then gave up and did the same. No one laughed. Anna lifted her first piece of bread slowly. The crust was firm under her fingers. The butter melted in yellow lines. When she bit it, the taste hit her so hard she had to close her eyes. She started to cry, silent tears running down cheeks already burned by the cold.

When the plates were empty, the sergeant filled them again without a word. Before they left, James took a paper bag, put in more bread, two cans of beans, a jar of peanut butter, another chocolate bar. He closed the top and placed it in Anna’s arms. She looked from the bag to his face, “You feed children of your enemy.” She said at last in slow English. The words felt heavy, important.

James shifted, embarrassed. “Kids didn’t start the war, Momm,” he answered. “They just got stuck under it.” For the next 3 weeks, he made sure they did not stay stuck. Every day he found a way to bring extra rations. A blanket here, a tin of peaches there, powdered eggs, more bread. Quietly, like a small crime, he moved food from the American side of the line to the German.

No one counted every egg. No one wrote down each can. Little by little, color came back to the children’s faces. Their bellies stopped swelling from hunger. Anna’s strength returned. Her milk came back so she could plan to feed the baby that would arrive in two months. A life was being built from other people’s surplus.

One morning, she came to the street carrying the only whole thing left from her old home. A small porcelain angel wrapped in newspaper. She tried to press it into James’s hand as payment. He shook his head and tried to give it back. She closed his fingers around it. “Thank you for my children,” she said. He kept the angel in his pocket for an hour, then fearing trouble, quietly slipped it back into her coat when she wasn’t looking.

“No pay,” he told her. “Just be okay.” She found it later at home and set it on the table where everyone could see. They did not know it yet, but this quiet exchange of food and a fragile angel would echo far beyond that winter. What came next would show how a few weeks of kindness could shape the long years of rebuilding that followed.

One morning, after three weeks of quiet meetings and shared food, James was not at the corner. Anna waited in the cold until her feet went numb. She watched each American patrol that passed, but none of the faces was his. The next day she came again, and the next for months she walked to that same spot, clutching her coat tight, hoping to see the tall soldier from Brooklyn with the easy smile and the heavy pockets. He never came back.

Like thousands of other occupation troops, he had been rotated home. Between 1945 and 1947, more than 1.6 6 million American soldiers passed through or stayed in Germany. Most left without a goodbye to the civilians they had quietly helped. Anna later wrote, “I kept a place for him in my day, as if he were a shift that would start again.

Back in the basement room, the porcelain angel sat in the middle of the rough wooden table. Its white glaze was smooth and cold under her fingers. When the children had birthdays, they touched its tiny wings and said, “Dunker, Americanisha papa. Thank you, American daddy.

” before they blew out their candles, even if the cake was only a piece of dark bread with a bit of sugar on top. The hunger did not end with James’s departure. The winter of 1946-47 was one of the worst in memory. Coal was short, food was short, and Berliners burned broken furniture to stay warm. Average rations in some months dropped under 1,000 calories a day.

A city official noted, “We are trying to rebuild an economy on the food level of a concentration camp. Then slowly, another kind of American help arrived. It did not come from one soldier’s pocket now, but from ships and trains. Between 1948 and 1952, the United States sent about $13 billion in Marshall Plan aid to Western Europe. West Germany alone received around $1.4 billion.

Money, machines, wheat, powdered milk. It was a huge number at the time, equal to more than $100 billion today. For Anna, these numbers became real in the weight of a cardboard box. One morning, a man from the post office brought a care package. It weighed about 20 lb, like the 10 million other care packages sent to Europe in those years.

Inside, wrapped in wax paper and brown bags, were things she had almost forgotten existed. Real coffee with its deep, bitter smell, white flour that sifted soft through her fingers. Canned meat. Sugar that shone like tiny crystals. Someone in America, a stranger, had written their name on the box. The same country that had bombed our city now sent us milk and chocolate.

Anna later told her children, “It was hard to understand, but my stomach believed it first, then my heart.” This was another paradox. The enemy as destroyer and the enemy as provider. This wasn’t propaganda. I mean, it was reality. And it filled her cupboards one can at a time. With a little more food, people could think about more than just staying alive. The city reopened schools. Training courses began.

Anna saw a notice for nursing classes funded with American aid money and church donations. She remembered the hospital wards during the war, the wounded soldiers, the crying mothers. Now she wanted to help heal instead of watch people die. She studied in an unheated classroom that smelled of chalk, wet wool, and carbolic soap.

Her hands that had once begged in the street now changed bandages and checked pulses. Within a few years she was working on a proper ward, walking between white beds, hearing the steady tick of wall clocks instead of the howl of air raid sirens. Her children grew with the city. Klouse, the boy whose lips had been blue in that cold street, loved machines.

West German factories, helped by Marshall Plan equipment, roared back to life. By 1950, industrial production in West Germany was already more than onethird higher than before the war. Klaus studied engineering and later helped repair and extend the autobond that war and neglect had broken. Leil, who had once refused to reach for chocolate from an enemy’s hand, fell in love with languages.

She listened to British radio, learned English from returning prisoners of war, read American books in cheap paperback form. She became a teacher and told her students, “Learn languages. It is harder to hate someone if you understand their words.” In 1950, Anna had her third child, Peter, the baby she had carried when James brought peaches to the mess tent table.

He grew up in a world where there was always bread, though his mother never let him forget the years when there was almost none. He studied hard and went to medical school, wanting, like his mother, to be on the side of repair. Through all these changes, the porcelain angels stayed on the table. Each visitor asked about it. Each time, Anna told the story of the tall American who fed her children and refused to be paid.

“We owe him our tomorrows,” she would say. By the early 1960s, West Germany was one of the strongest economies in Europe. New apartment blocks rose on the sights of old ruins. Shiny cars hummed along smooth roads where tanks had once ground past. But inside Anna, there was still an unanswered question.

Did James know what his food had done? Did he know they had lived? In 1962, she sat down at that same table, now in a rebuilt flat, the angel in front of her. The room smelled of coffee and floor polish instead of coal dust. With careful, slow English, she wrote a letter to Private James O’ Conor, US Army, Brooklyn, New York. the only address she could guess. She told the story from her side.

She described Klouse the engineer, Lizel, the teacher, Peter the medical student. At the bottom, she wrote, “Because of you, we got to grow up. Your German family, Anna, Klouse, Lizel, and Peter.” She added a small photograph of the three tall teenagers standing proudly in front of their new apartment block.

Then she took the letter to the Red Cross asking if they could help find the man who had once called her children kids in a warm New York voice across the ocean in a city he now protected with water instead of weapons. That letter would soon find its way into James O’ Conor’s hands and pull him back to a snowy Berlin street he had never really left. Brooklyn, December 1962. Cold wind blew off the East River, carrying the smell of diesel, garbage, and distant smoke from oil burners.

In a narrow brick house above a busy street, James O’ Conor hung his New York City fireman’s coat on a hook by the door. The cloth still smelled faintly of smoke and wet hose water. His hands were rough, his hair starting to gray at the temples.

He was 40 now, married, with three children, who ran to hug his legs as he came in. In the years after the war, James had traded his army uniform for a fireman’s one. The tool in his hands was no longer a rifle, but a hose or an axe. In the early 1960s, the fire department of New York answered more than 100,000 alarms a year across the city.

“Feels like half of them come on my shift,” he sometimes joked to his crew. He saved people from burning buildings the way he had once tried to save them from burning cities. On the kitchen table that evening lay a thin blue envelope, longer than normal, with strange stamps in the corner. His wife wiped her hands on a dish towel and nodded toward it. Air mail, she said.

From West Germany. It’s in English, but she picked it up and turned it over. Look at the writing. It’s like someone practiced every letter. James took the envelope. The paper felt lighter than American envelopes, almost fragile. On the back he saw a return address in a place name he did not know and a woman’s name Anna Schaefer. The sound of that name pulled at something deep in his memory like a tune half remembered.

He slid a finger under the flap and opened it. A photograph fell out first and landed face up on the table. Three teenagers stood in front of a new apartment building. Two tall boys and a girl, all in their late teens with dark coats and careful smiles.

Behind them, the building was clean and modern with wide windows and balconies, no rubble, no smoke. On the back of the picture was a short line written in neat, careful English. To private James O’ Connor, you once told my mother children didn’t start the war because of you. We got to grow up. Your German family, Anna, Klouse, Lizel, and little Peter. James read the words, then read them again.

The kitchen sounds faded. He sat down hard on the chair. His wife, alarmed, asked, “Jim, what’s wrong?” For a moment he could not answer. At last he pushed the photograph across the table. “These,” he said slowly, “Ash are my German kids. Inside the envelope was a longer letter, four pages, written in that same careful hand.” “The Red Cross tracing service had helped it find him.

In the years after the war, Red Cross offices in Europe and America handled millions of such requests, trying to connect lost families and lost helpers. Now, one of those lines had reached all the way from a rebuilt Berlin flat to a Brooklyn kitchen. Anna told her side of the story, how she had waited at the corner for months after he left, hoping to say a real goodbye, how the winter of hunger had nearly broken them, and how the first care packages and Marshall Plan aid had slowly filled their shelves. She wrote about the porcelain angel he had refused to take, and how it

had stood on their table for 16 years. Every birthday, she wrote, “My children kiss the little angel and say, “Thank you, American Daddy.” before they eat the cake. Reading that, James had to put the letter down for a moment. He saw again in his mind the blue lips of a small boy, the thin fingers of a girl clutching chocolate-like treasure, the smell of coffee and eggs in the mess tent. He had never thought of himself as anyone’s daddy.

In his memory, those three weeks in Berlin had been just something decent he could do with the extra Krations that no one would miss. An American soldier’s daily ration then was almost 4,000 calories. In Berlin, that made him richer than any banker. We had more food than we could eat, he later told a friend. They had more hunger than they could bear. Anna’s letter went on.

Klouse was now an engineer helping rebuild the autob barn. Lizel taught English in a school full of children who had never seen war. Peter, the baby she had been carrying when James first brought peaches to the table, was in medical school. At the bottom, she wrote, “If you ever want to visit, our door is open. You will never pay for a meal in our house. Never.

” James took the letter to the firehouse. The room smelled of coffee, oil, and the faint sourness of old smoke in the gear. His crew gathered around as he read parts of it aloud. Big men who ran into burning buildings shook their heads slowly. One of them slapped James on the back. “You can’t not go,” he said.

“We’ll get you there.” The firehouse had about 20 men on its roster. Part of the roughly 6,000 firefighters in New York at the time, they passed a helmet around and stuffed in bills. Within weeks, they had enough to help pay for tickets. By 1963, more than a million passengers crossed the Atlantic by air each year, a number that would have stunned people before the war.

Now, one of those seats would carry a Brooklyn fireman back toward the city he had once entered with a gun. In the summer of 1963, James, his wife, and their three American children boarded a Pan-American flight to Frankfurt. The cabin smelled of fuel, coffee, and nervous excitement.

As the plane climbed over the ocean, James looked down and thought of the other crossing in 1945 in a troop ship that had creaked and rolled for days. At Frankfurt airport, bright and busy. They saw a small group waiting by the barrier. An older woman with silver in her hair, a tall young man, a young woman with a teacher’s calm eyes, another man in a student’s coat.

They held flowers and a cardboard sign with welcome James O’ Connor written in uneven English. When they saw him, they rushed forward. The moment their arms went around each other, fireman’s coat against German wool, former occupier against former occupied. Cameras clicked. A local reporter wrote the next day, “Former enemies embrace at airport.

” The picture showed James, small and stocky among three tall Germans. all of them laughing and wiping at their eyes. He had once stepped onto German soil as part of an army of conquerors. Now he arrived as a guest, a friend, even something like a father. This wasn’t propaganda, but it was reality, and it showed how far both sides had traveled since that starving winter.

In the days that followed, that truth would grow even stronger, as James saw with his own eyes how the country he had helped defeat had rebuilt, and how the family he had once fed now wanted to feed him in return. In 1963, James and his family spent 2 weeks in West Germany. It was not the gray, broken place he remembered from patrols.

Streets were clean. New shops glowed with glass windows. Cars rolled past with a soft hum instead of tank treads. In the years after the Marshall Plan, West German production had soared. By the early 1960s, industrial output was more than three times higher than in 1947. People called it the economic miracle. Inside Anna’s apartment, the miracle felt simple.

Warmth, full plates, and loud laughter. She gave James and his wife the best bed in the house with thick feather quilts that smelled of sun and soap. She and the grown children slept on sofas and floor mattresses without complaint. At dinner she set out the largest portions of meat for James, beef steaks thick as his palm, potatoes fried in butter, bright green beans with slivers of bacon. The room filled with the smell of roasting fat and onions.

You have to eat, she scolded gently when he tried to give food back. You made them big, she said, nodding at her children. Now I make you big. Beer bottles sweated on the table. Glasses clinkedked. When James reached for a plate to help clear the dishes, Anna almost slapped his hand away. Nine, she said firmly. You did enough work in Germany. Here you rest.

Her voice was light, but her eyes were serious. In the evenings they sat in the small living room, the children, now young adults, crowded close, knees touching. They wanted stories about Brooklyn, the noise of the elevated train, the smell of hot dogs on Coney Island in summer, the way fire engines sounded on narrow streets between brownstones. “Tell us again about your first fire,” Peter would say. “Tell us how high the buildings are.

” One afternoon, James took them to a patch of grass behind the building. He had brought a baseball and a glove in his suitcase tucked between shirts. The leather smelled of oil and dust. The German neighbors leaned from balconies, puzzled, as he showed Claus how to throw, Lizel how to swing.

Each crack of the ball on the bat made the courtyard echo. In 1945, we heard only explosions. Anna later said, “Now, in that same air, we heard our children laughing. On the last evening, when the dishes were done and the house was quiet, Anna led James to a shelf near the table. On it stood the small porcelain angel, its glaze still smooth after all the rough years.

She picked it up and placed it gently in his hands. “We survived because of you,” she said, her voice low but clear. “Gy survived because of people like you. The room smelled of coffee and polish, not coal and fear. James tried to make a joke. “I just gave away some extra rations,” he said, looking down, suddenly shy.

In his mind, he still saw himself as a young private sneaking food from a busy kitchen, “Not as someone who had changed a family’s history.” Anna shook her head. “No,” she answered. “You gave us tomorrow.” He did not have words for that. He just nodded and put the angel back on the shelf. It stayed there, the quiet center of their story.

After that visit, they did not disappear from each other’s lives. Letters crossed the Atlantic written in careful English and slangfilled Brooklyn talk. Sometimes there were phone calls, too, though the crackle on the line made voices thin and far. In 1970, West Germany had more than 10 million telephones installed, a sign of how far it had come from the days when Anna’s only link to Americans was a single patrol on a ruined street.

As the years passed, the bond between the former occupier and the once starving family changed shape again. James’s American children grew up hearing about the German kids. Klouse married and had children of his own. Lazel’s students learned English not only from textbooks, but also from stories of the firemen from Brooklyn who had taught her small phrases in the ruins.

Peter finished his studies and became a heart surgeon in Munich, working in bright operating rooms where clean steel and strong lights replaced the dirt and darkness of wartime sellers. People outside their circle still carried old ideas. Some Americans saw Germany only as the country that had started two wars.

Some Germans still remembered bombings more than chocolate bars. But inside this small group, another truth had taken hold. The man who once came with an army was now called with love. In 2003, another air mail envelope arrived at the old Brooklyn firehouse addressed to James, now retired and gay-haired. Inside was a formal printed card and a handwritten note from Peter. The card invited him to a wedding in Munich.

The note added, “I am the baby my mother carried when you gave us peaches. I am now a heart surgeon. You are my American grandfather. Please come. The ticket is paid.” James’s grandchildren helped him pack. On the flight, the cabin buzzed with talk. The air smelling of coffee, plastic trays, and recycled air. As they landed, he thought again of the first time he had seen Germany from the ground. smoke, ruins, and hungry faces.

Now he stepped into a modern airport of glass and steel, with bright shops and polished floors. The wedding hall glowed with light. Tables were set with white cloths and shining silverware. The smell of roast meat, wine, and perfume filled the air. About a hundred guests sat and whispered, curious about the elderly American at the front table.

When it was time for speeches, Peter stood up in clear German and then in practiced English. He said, “This is the man who fed my mother and my brother and sister when there was almost no food in Berlin. Without him, I would not be here. He came to our country as a soldier. Today, he is here as our grandfather.

” The room went still. Then people began to clap, some wiping their eyes. When the band started to play, Peter’s new wife went first. Not to her husband, but to James. “You saved his life before he was born,” she said. “The first dance is yours.” He held her hand light in his rough palm, and they moved slowly across the floor while everyone cheered.

Once James had walked German streets with a rifle and full ammo pouches. Now he crossed a German dance floor with a corage on his lapel and a full heart. This wasn’t propaganda. It was reality. And it showed how far enemies can travel when they choose. Care over hatred. Yet one last journey still waited for them all.

A final meeting where the story of the porcelain angel, the hungry winter, and three generations of thanks would come together in one quiet act beside a wooden box in Brooklyn, Brooklyn, 2011. The air outside the small church was cool and smelled of rain on pavement and car exhaust. Inside, the light was soft. Candles burned at the front, giving off a faint scent of wax and smoke.

A wooden casket stood near the altar, covered with an American flag and a New York Fire Department helmet. James O’Conor had died peacefully at the age of 88, close to the average lifespan for American men in that year. His children and grandchildren filled the front pews.

Old firemen in dress uniforms sat together, their medals catching the light. A pair of bag pipes rested against a wall, waiting to play their slow, sorrowful song. Then the doors opened and four people stepped quietly into the back. One tall man with gray at his temples, one woman with a teacher’s posture, another man with a doctor’s steady hands, and between them walking carefully with a cane, a very old woman with white hair pinned in a knot.

It was Klouse, Lizel, Peter, and their mother, Anna, now in her 90s. They had flown more than 6,000 kilometers across the Atlantic to say goodbye. Once James had come to their country with tens of thousands of other soldiers, part of an army of occupation. Now former enemies crossed the ocean to stand at his coffin as family.

In Anna’s hands was a small parcel wrapped in cloth. She held it as if it might break, even though it weighed almost nothing. As they moved up the aisle, she could smell polish on the wooden pews, incense in the air, and the faint clean scent of laundry soap from the black suits around her. The floor creaked under many careful feet.

When they reached the front, the priest nodded and stepped aside. Anna’s fingers shook as she unwrapped the cloth. The porcelain angel shone in the dim light, its white surface still smooth after more than 60 years, its tiny wings unchipped. Once in 1946, she had tried to give this angel to a young American as payment for food he would not let her pay for. He had quietly refused it, slipping it back into her coat.

Now on this day, she finally placed it where it belonged, on the flag over his casket. The porcelain was cool against the rough cloth. For a moment, the only sound in the church was the soft click as she set it down. The priest opened a paper in his hands. His voice was steady as he read words Anna had written with Peter’s help in simple English.

When the world had almost no bread left, the letter said, he shared his bread with my children. Because of him, three generations in my family tried to carry kindness in their hearts. People in the pews dabbed at their eyes. Some had never heard this story. Later, Peter would say, “We did not come to bury a soldier. We came to bury our American grandfather.

” Lizel told one of James’s granddaughters, “Your grandfather taught me my first real English words. Now I teach them to others.” Klaus shook hands with the firemen who had helped send James to Germany in 1963 and said, “Without you, he might never have found us again.

” World War II had killed more than 60 million people across the globe, soldiers and civilians from many nations. More than 400,000 of them were American and several million were German. The numbers were almost too large to understand. Against that huge sea of loss, the story of one man, one woman, and three children might seem small. Yet their story showed a quiet truth that statistics alone could not.

The war had begun with leaders who shouted hate into microphones and radios. It ended in part with a private first class handing chocolate to children and with those children crossing an ocean as old people to thank him. By 2011, Germany and the United States had been allies in NATO for more than 60 years.

Around 50,000 American troops were still stationed on German soil, not as occupiers now, but as partners. German companies built cars in American towns. American students drank coffee in Berlin and Munich. They had come as conquerors, they left as students, learning from each other how to rebuild and how to live in peace. As the bag pipes finally began to play, their sound filling the church with a deep, sad music, the porcelain angel stood watch on the casket.

It was a small, silent bridge between the hungry winter of 1946 and the safe goodbye of 2011. Long after the service ended, people would remember that simple image, a flag, a helmet, a tiny white angel. It was proof that this wasn’t propaganda. It was reality. and that one act of kindness on a snowy Berlin street could echo further than any gunshot. In the years since James first walked through ruined Berlin, both his country and Anna’s changed almost beyond recognition. Bombed streets turned into busy shopping avenues.

Children once marked as the enemy grew up to work in hospitals, schools, and engineering firms that helped power a peaceful Europe. Former war zones became tourist stops where people bought postcards instead of firing shells. But beneath all those big changes lay the same simple choice James made when he reached into his pocket to follow what he saw with his own eyes instead of what he had heard on the radio. They had come as conquerors.

They left as students, learning that even in war, humanity can cross the lines leaders draw. In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its bombs, but its abundance and the quiet courage of ordinary people willing to share

News

ch2-ha-How a US Sniper’s ‘Helmet Trick’ Destroyed 3 MG34s in 51 Minutes — Saved 40 Men With ZERO Casualties

How a US Sniper’s ‘Helmet Trick’ Destroyed 3 MG34s in 51 Minutes — Saved 40 Men With ZERO Casualties At…

ch2-ha-Why Francis Sherman Currey Was The Scariest Soldier of WW2

Why Francis Sherman Currey Was The Scariest Soldier of WW2 So when I graduated high school, I was 17 years…

ch2-ha-They Told Him Never Dogfight a Zero – He Did It Anyway

They Told Him Never Dogfight a Zero – He Did It Anyway As we started the push over, about…

ch2-ha-German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia,…

ch2-ha-“It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

“It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier May 12th, 1945. Camp…

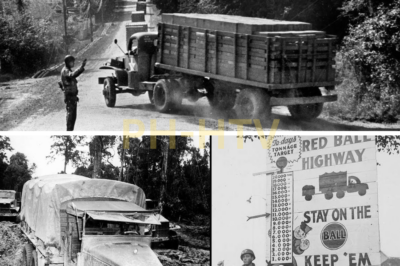

ch2-ha-German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz August 19th, 1944. Vermacht headquarters, East…

End of content

No more pages to load