“It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

May 12th, 1945. Camp Swift, Texas. The air was so hot it seemed to shake above the sand, and the tin rubes flashed like knives in the sun. A line of captured German women stood silent in the dust, while a young American medic walked past them with a clipboard, bored, just ticking boxes, height, weight, scars.

Then he touched one woman’s shoulder gently, and she flinched like he had pressed a brand of fire into her skin. Her voice was calm, but her words were not. It burns when you touch it. Under that scar was a secret she had carried across a continent and an ocean. A hidden piece of war that would shock the US soldier who found it and destroy everything they both thought they knew about the enemy.

If you want more true World War II stories told like a movie, please subscribe, like this video, and stay with me to hear the full story of the German woman p. The hidden injury and the touch that changed both their lives. Germany, early 1945, the Third Reich was falling apart. Town after town shook with artillery. Roads were full of soldiers and civilians moving west trying to escape the front.

In a small village near the Ludenorf Bridge at Remigan, a 23-year-old German woman named Margarite Hoffman worked in a signals unit. She was a chemist’s daughter from H Highleberg trained to handle radio messages, not weapons. Her work was supposed to be safe behind the lines. That was the lie. One cold day in January, American guns began to fire on the area.

The air shook with the deep thump of shells. Windows rattled. Dust fell from rafters. Margarite and other staff ran for a cellar. She felt a hard blow across her back like someone had hit her with a hot hammer. She stumbled, but did not fall. She did not know it yet, but a small fragment from an 88 mm shell had punched into her right shoulder blade and stopped near her ribs. Her uniform smoldered.

The air smelled of smoke, lime dust, and burned cloth. Later, she would say, “At first, I thought it was only a bruise. Only when I lay down at night, it burned. In the chaos of retreat, there was no time for careful treatment. Field hospitals were overflowing. Infections spread easily where bandages and medicine were short.

One German nurse later wrote, “We sometimes had one doctor for hundreds of wounded. We cut away cloth with dirty scissors and prayed.” Margaret had seen these places. She had heard rumors that badly wounded women were sent away and never came back. So she made a choice. She hid her wound.

As her unit fell back toward the rine, she kept her right arm close to her body. The spot under her shoulder blade felt hot, as if a coal was trapped under the skin. Each bump in the road made fire shoot down her side. Still, when someone asked, “Britlet, are you hurt?” She always answered, “No.” In March, American infantry reached their village.

Tanks clanked in the streets, boots pounded overhead, while Margaret and six other women hid in a farmhouse cellar. They had been told all their lives that Americans were monsters. One Nazi leaflet said the Yankee will shoot prisoners like dogs. A captured Clark later recalled, “We expected to be lined up and killed. Instead, when they came up with their hands raised, the Americans looked almost uncomfortable. One soldier offered water.

Another asked in broken German if anyone was wounded. Margaret shook her head. She remembered. They said the injured would be taken away to other places. I did not want to vanish. The paradox was sharp. She trusted enemy horror stories more than the man holding out a canteen. From that point, her world turned into numbers and lists.

The women were sent to a temporary camp, then another. Names were recorded, heights and weights written down. Photographs were taken. They were sorted by jobs, nurses, clerks, farm workers, like items on a shelf. By 1945, around the 425,000 German prisoners of war would be shipped to camps in the United States. To move them, the Allies used trains, then Liberty ships.

Each Liberty ship could carry more than 2,000 troops or prisoners across the Atlantic at once. Margaret and 14 other women were loaded into a cattle car, straw on the floor, a bucket in the corner. Through the wooden slats, they saw Germany slide away, then France, then the ports. At the harbor, the smell of tar, salt, and diesel filled the air.

Chains rattled as cranes lifted crates and vehicles. When the prisoners were marched up the gang plank, some stared at the gray hull of the ship and thought they might never see land again. One P later wrote, “We did not know if we were going to work or to disappear. The crossing took nearly 2 weeks. The sea was rough.

Many were seasick. The holds smelled of vomit, sweat, and fuel oil.” Margaret lay on her bunk, cradling her right arm. The skin over the fragment was red and tight. At night, the pain woke her like a burn. She pressed her hand against it and felt heat. Still, she stayed silent.

When the ship reached New York, the prisoners caught glimpses of the harbor through small openings, tugs hooting, gulls crying, the distant shape of tall buildings. Some saw the Statue of Liberty and laughed bitterly. Freedom for them meant barbed wire. Soon they were moved again into trains heading inland. Guards tried to explain in simple words. Many of the prisoners heard one name repeated, Texas.

They had seen pictures of cowboys and deserts in magazines, but nothing more. To them, Texas was as strange as the moon. By that summer, tens of thousands of German PS would be scattered across camps in that state, working on farms and roads that were not their own. As Margaret’s train rolled south, the air grew warmer.

Dust came in through the cracks. Her shoulder throbbed with each mile. She pressed it harder against the wooden wall, trying to hide the way she winced. Somewhere ahead waited a camp called Swift, and a young American medic, who would not accept her quiet lie. Camp Swift lay on flat land about 20 mi east of Austin.

Low scrub trees, red dirt, and long rows of white barracks stretched under a hard blue sky. In summer, the heat pressed down like a hand. Dust got into everything. Boots, beds, food. By mid 1945, Texas held about 80,000 German prisoners across more than 70 camps, and Camp Swift alone could hold more than 10,000 soldiers and PS at one time.

In the mornings, the camp woke to the clang of the mess bell and the smell of coffee and bacon fat drifting from the kitchens. On the American side of the wire, men complained about paperwork and drills. On the German side, many prisoners were surprised to find three hot meals a day and real mattresses. One P later said, “We ate better there than in the last winter at home. It was confusing.

” Corporal Thomas Reed felt confused in another way. He was 26 from Chicago, the son of a pharmacist. He had trained for combat, learned how to fire a rifle, how to move under machine gun fire. Then a training accident shattered his leg. Now a steel rod held the bone together. Instead of Europe, he got sent to Camp Swift to work in medical administration.

His days were mostly forms and numbers, height, weight, scars, vaccinations. He checked German men who went to road crews, sawmill details, cotton fields. The paradox stung him. He had prepared to fight Germans with a gun, and now he handed them soap and recorded their blood pressure. The arrival of women changed the pattern.

One hot May afternoon, two trucks rolled up with 15 German women in faded gray uniforms. Dust swirled around their boots as they climbed down. They stood straight, eyes forward, faces closed. Female US Army personnel, Wax, took charge of them, separate from the men. The women were sent to their own fenced area, their own barracks, their own work in laundry and kitchens.

Word spread quickly through the camp. Fraen women prisoners, some guards said with surprise. Most PWs were young men. Whole groups of women were rare. Reed watched from the doorway of the medical hut as the new arrivals passed. One of them, slim with hair tied back and a tired face, held her right arm close to her side. Even in the heat, she seemed to shiver when the truck jolted.

The next morning, Reed was told to perform medical checks on the new group. The exam room was a converted barracks, bare floorboards, a few chairs, a metal table, a cabinet of supplies that smelled faintly of alcohol and carbolic. A fan turned slowly overhead, pushing warm air around. Outside, boots thumped, and someone shouted orders in English. The women came in one by one. A whack stood near the door, arms folded, watching.

Reed worked through the first few quickly, names, ages, lungs listened to through a cold stethoscope, backs checked for scars or rashes. His pen scratched across the forms. Most women were thin, but healthy enough. The woman with the guarded arm was seventh in line. When her turn came, she stepped forward quietly.

Up close, Reed saw she was younger than he first thought. early 20s. Lines of dry dust on her cheeks. Her gray jacket hung unevenly. The right sleeve hardly moved. Name? He asked. Margaret Hoffman, she answered in careful English. He raised his eyebrows. You speak English well. I learned in school. My father is a chemist in H Highleberg, she said, then fell silent.

Any illness? Any wounds or pain? Reed asked the usual question. She paused just a second too long, then shook her head. No, I am well. Reed frowned slightly. He had seen prisoners fake sickness to avoid work, but this felt different. She was hiding something. Still, procedure was procedure. Please take off your jacket, he said. She unbuttoned it with her left hand only. The right stayed close to her side as if pinned there.

When she slid the jacket off, Reed noticed how stiffly her shoulder moved. Under it, her cotton shirt was thin and yellowed. He listened to her heart and lungs. They sounded steady. Then he said, “Raise both arms, please.” Her left arm went up without trouble. Her right lifted only a few inches before she gasped and stopped. Her face went pale. Muscles in her jaw tightened as she clenched her teeth.

Reed saw the skin over her shoulder twitch under the cloth like something was pulling from inside. “You are hurt,” he said softly. “It is nothing,” she whispered. “It will pass.” He reached out and placed his fingers lightly on the back of her shoulder through the shirt. “At that small touch, she flinched as if burned.

Heat came through the fabric, hotter than the air in the room. She sucked in a sharp breath and closed her eyes. Near the door, the wax supervisor shifted impatiently. “Corporal, we need to finish this group,” she reminded him. Reed let his hand drop, but his mind was now fixed on this puzzle. The camp rule book said to note injuries and send serious cases to higher care.

The prisoner rule book, unwritten but strong, told Margaret to stay silent. She stood there breathing carefully, her right arm back against her chest. I can’t help you if you don’t tell me the truth, Reed said quietly. Her eyes met his for a brief moment. There was fear there, but also something like refusal.

Please, she said, no hospital, no separation. He finished the form with neutral words, but he did not forget her face or the strange heat under his fingers. Later that day, a German prisoner who spoke good English told him, “You must understand, Corporal. We were told, “Your kindness is the first trick. If we accept it, we begin to doubt everything.

” That evening, Reed looked again at Margarit’s file. Age 23. Captured near Remigan. Occupation, communications, all facts, no feeling. The paper did not mention the way she had trembled when he touched her shoulder. The next time he spoke with her with another woman acting as translator, Margarite finally gave him a few more words about the hidden wound. “It burns,” she said, her voice low.

“It burns when you touch it.” But to find out why, he would have to win something rare in a prison camp. Her trust. Reed could not stop thinking about the heat he had felt under Margarit’s shirt. The next day, he went to his commanding officer and asked for permission to do a closer exam in private.

The officer frowned at the extra work, but agreed as long as a wac stayed in the room, and rules were followed. That evening, Margaret was brought to the small medical office. It smelled of rubbing alcohol and old wood. A single bulb buzzed overhead. The WS sergeant stood by the door, arms crossed. Reed spoke gently, using slow English and simple words.

“I need to see your shoulder,” he said. “The real problem.” She hesitated, then nodded once. With her left hand, she unbuttoned her thin shirt and let it slide down to her waist. The skin of her right shoulder blade was a map of old damage. Shiny twisted scar tissue in the center, red at the edges where infection still fought. When Reed’s fingertips moved lightly over it, he felt something hard under the skin, like a small stone.

Heat came off the spot, warmer than the rest of her back. “How long?” he asked. “Since January,” she answered quietly. “He did the math. 4 months with a metal fragment near bone. 4 months of the body trying to fight it with no real medicine. He knew what that could mean.

Bone infection, blood poisoning, slow death.” In one US Army medical report from 1944, doctors wrote that untreated deep wounds could kill more men than bullets did on the day of battle. Reed straightened up. This must come out, he said. Soon it’s dangerous. Margaret pulled her shirt back up, moving carefully. “No hospital,” she said at once. “No operation.” “Why?” he asked.

“In Germany,” she said, searching for words. The badly hurt was sent away. We did not see them again. In the field stations, I heard men scream all night. No medicine, no clean tools. I would rather stay here. Later, she told another woman in German, better to die quietly among people, you know, than on a table among strangers. It was not logic in a book.

It was logic built from what she had seen and heard. Reed argued as best he could. He explained that in America there were trained surgeons, clean rooms, and drugs that killed germs. By 1945, the United States was producing hundreds of millions of units of penicellin and millions of tablets of sulfur drugs every month.

Frontline hospitals were far better supplied than anything the German army could manage at the end of the war. But to Margarite, these were just words from an enemy uniform. For 3 days, he tried. He spoke to her after work details beside the laundry steam that filled the air. Always the same answer. No hospital.

Other women began to notice. One evening, as the sun went down and the camp cooled a little, an older prisoner came to find him near the messaul. Her name was Gertrude. She had worked as a translator before the war and spoke clear English. She is afraid you will hurt her. Gertrude said simply, “Not because you are cruel, because you do not know her.

She has seen men cut open with little morphine. She thinks it is better to let the wound decide than the surgeon.” Reed listened, then said, “Please tell her this. I give my word. We will not let her suffer. We have the best drugs here. Real medicine, not what she knew near the front.” Gertrude studied his face for a long second, as if weighing his honesty.

Words are easy, she said. She will need more than that. That night, Reed had an idea. The next morning, he signed out the key to the dispensary cabinet. The small room was cool and dim, lined with shelves. Glass bottles and metal trays shone softly. The smell of antiseptic was strong, sharp in the nose. He brought Margarite there with a guard watching from the doorway.

He opened the cabinet and showed her what was inside. Rows of clear glass ampules filled with morphine, white tins of sulfur powder, rolls of sterile bandages, stainless steel instruments wrapped in clean cloth. He let her hold a bottle, feel its weight in her hand, read the English labels slowly. This is what we use, he said. This is not a frontline tent. This is Texas. We have enough here. For a long moment, she said nothing.

The light caught the glass in her fingers. She had been told that Americans were savages, that prisoners would be starved, beaten, left to rot. Instead, she was holding more medicine than most German units had seen in months. This wasn’t propaganda. It was reality, sitting cold and solid in her hand.

“You promise?” she whispered at last. “You promise I will not wake up in screaming pain?” “I promise,” Reed answered. “We will make you sleep. We will take the metal out. then you can heal. She looked at him, then at the cabinet again. Something in her eyes changed. Less like a wall, more like a door, just slightly open. Finally, she nodded. I will sign.

That afternoon, he filled out the forms to send a surgeon from Fort Sam Houston, and to transfer her to the base hospital north of the camp. Paper moved slowly, but the infection moved faster. Within days, approval came.

The next step would take her out of the wire into a place where knives and lights and foreign hands could either kill her or save her. The army truck rattled along the road north from Camp Swift. Dust rose behind it in a long brown tail. Inside Margaret sat on a bench, her right arm in a makeshift sling, a guard across from her and Reed beside her. The air smelled of hot canvas and engine oil.

When the truck hit a bump, pain flashed from her shoulder down her back, but the fear in her stomach felt even sharper. The base hospital sat on the edge of a larger training post. Long, low buildings painted white, screened windows, a small line of trees trying to give shade. Compared to the rough barracks of the camp, it looked almost gentle.

Inside, the cool hit her first. fans turning, polished floors, the strong smell of soap and disinfectant. Nurses in white moved quickly but quietly, pushing carts that rattled with metal trays. By 1945, the US Army had built a huge medical system. More than 300,000 beds stood in military hospitals around the world.

Surgeons did millions of operations on Allied soldiers, often with good supplies of blood, penicellin, and sulfur drugs. For many German units at the end of the war, such numbers would have sounded like fantasy. A nurse took down Margarit’s information while Reed spoke with the surgeon, a tall man with gray at his temples and major’s leaves on his collar. His name was Pritchard.

He had operated in North Africa and Italy before being sent back to the United States. In the exam room, Pritchard ran experienced fingers over the scar on her back, pressing gently. When he found the hard point under the skin, he let out a low whistle. Shell fragment? He asked Reed. That’s what she says. Since January, Reed replied. 4 months? The surgeon shook his head. It’s a wonder she’s still walking.

To Margaret, he said in slow English, “We will need to go deep. There is infection around the metal, but we can do this.” She signed the consent form with her left hand. Her right lay still at her side. That night, she lay awake in a narrow hospital bed. Clean sheets scratched softly against her skin. Somewhere nearby, someone coughed. Footsteps clicked past her door. She thought of the field stations she had seen in Germany.

Torn uniforms, dirty bandages, men biting on straps as sores worked. Here the tools were clean and wrapped. The paradox pressed on her. The enemy she had been taught to fear was about to try to save her life. In the early morning, orderlys came with a rolling stretcher. The wheels hummed over the floor. They lifted her gently. A nurse adjusted the sheet over her.

The lights in the corridor were bright. The doors to the operating room stood wide, metal edges shining. Reed was not allowed inside. He sat in the waiting area, where the coffee was bitter, and old magazines lay in a messy pile. Every so often a stretcher squeaked past or a nurse called out a name.

Time seemed thick. He thought about the small hot spot under her skin, about bone and blood, and how easily both could fail. On the table under the operating lights, the air was cold on Margaret’s skin. A mask came down over her face. “Breathe deep,” someone said. The smell of anesthetic was sharp and sweet. The ceiling blurred, then dissolved.

The surgery took nearly 3 hours. Pritchard later explained to Reed that the fragment was lodged between the scapula and the third rib, wrapped in tough scar tissue and pockets of pus. They had to cut carefully, clear away dead flesh, wash the wound again and again with antiseptic, then pack it with sulfur powder and gauze. Another month, he said, and the infection might have reached the bone.

After that, he let the sentence fade. When he came out, still in his green gown, he held a small glass vial. Inside, floating in clear fluid, lay a twisted piece of dark metal about the size of a fingernail. German 88 mm, most likely, he said. Quite a traveler, Reed took the vial. It felt heavier than it looked.

He held it up and watched the metal glint. That tiny shard had crossed a village, a country, an ocean, and now sat trapped in 3 in of glass. Such a small thing, he thought, for so much pain. When Margaret woke later, her shoulder felt thick and dull, wrapped in tight bandages.

There was pain, but it was different, deep and sore, not the sharp burning that had haunted her for months. A nurse checked her pulse, then smiled. “It went well,” she said. The metal is out. They showed me. Margaret told Reed when he visited that afternoon. Her voice was soft, a little blurred with morphine. They let me hold it. 4 months it tried to kill me, and now it sits in a bottle.

Over the next 2 weeks, she stayed in the hospital. Nurses changed her dressings every day. The wound oozed less each time. Antibiotics did the work her body alone could not have done. On the next bed, an older German prisoner named Ernst, a teacher from Breman, watched how Reed brought books and a small bunch of roadside flowers.

He is kind to you, Ernst said in German one day. Unusual for a guard. He is a medic, she answered. He sees a patient, not just a prisoner, Ernst stared at the ceiling. What did we become? He murmured. That such simple kindness can surprise us so much. Outside the screened windows, Texas sun baked the training grounds. Trucks moved. New soldiers drilled.

The war in Europe was ending. But the story in this ward was different. An American saving a German and a German learning that not all she had been told was true. Soon the bandages would grow lighter, the stitches would hold, and the hospital would send her back to Camp Swift, to work, to heat, and to a different kind of harvest under the wide sky.

When Margarite returned to Camp Swift in early summer, the air felt like a wall. The hospital’s cool halls were gone. In their place were long days of dry heat, buzzing insects, and dust. Her right arm rested in a proper sling now. Under the bandages, the wound pulled and itched, but the burning coal of pain was gone. The other women noticed a change before she spoke of it. She smiled more.

She joined small jokes in German. Sometimes, while folding laundry in the steamy wash house, she hummed old songs from before the war. One of them later said it was as if a weight had been cut out of her body and her mind at the same time. Reed saw the difference, too.

At each checkup, he watched her raise her arm a little higher. The scar was ugly but clean. No more heat, no angry red edge. He marked her progress on simple charts. At the same time, news filtered into the camp. Germany had surrendered in May. Radios spoke of occupation zones, trials, and rebuilding.

The war that had thrown them together was ending, but their strange shared time was not over yet. That August, the women’s routine changed again. Texas cotton was ready. White bowls covered fields that seemed to go on forever. In 1945, American farmers harvested millions of acres of cotton, and in Texas alone, more than 5 million acres were planted. With so many men still in uniform, farmers lacked hands.

Prisoners filled the gap. Buses and trucks carried German PWs from the camp to the fields at dawn. Men and women together, watched by a few guards with rifles slung over their shoulders, climbed down into the dust. The sun was already warm. By midday, it would be hard to breathe. Each prisoner was given a long sack and a simple instruction spoken in English and signs. Pick.

The work was rough on skin. Cotton feels soft when woven. But the plant’s dry bracks are sharp. Fingers bled. Backs achd. The air smelled of soil and sweat, and the faint green scent of crushed leaves. Guards walked the roads, calling out for water breaks. From time to time, a truck came with barrels of cold water and tin cups.

For many prisoners, it was the hardest labor they had done in months, but also the most familiar. One recalled, “We were back in fields like at home. Only the sky was different.” Margaret’s shoulder complained at first. Every reach pulled at the healing muscles. She worked slowly, using her left hand more, testing how far she could stretch the right. Reed came out sometimes with the camp doctor, checking for heat stress.

He would stop by her row, asking how is the arm. She would answer, “Better.” And this time it was true. The paradox in those fields was sharp. These people had once worn enemy uniforms. Some had helped send shells across rivers and bombs across cities.

Now they bent over American soil, helping bring in a crop that would clothe the country that had beaten them. Around 100,000 German PSWs across the United States worked in agriculture that year picking fruit, cutting timber, and like here picking cotton. This was not propaganda. It was everyday life born from need on both sides.

Yet the guards no longer looked like the monsters from Nazi posters. They joked past water, warned prisoners not to work too fast in the heat. At night, back behind the wire, Margaret wrote to her father in H Highleberg. She told him about the fields, the sun, the strange kindness she had found. “We are still prisoners,” she wrote.

“But we are not treated as animals. It is confusing to remember what we were told about these people,” Reed also wrote home to his family in Chicago. In one letter, he described a young German woman who carried a piece of our artillery in her shoulder. across an ocean.

He admitted that helping her had changed something in him. I was trained to break bodies, he wrote. But here I stitch, record, and reassure. The enemy has faces and names that is harder to live with, but perhaps better. As the cotton harvest ended, and cooler air came, at last, orders began to shift. Some PS were told they would soon go home.

Others would stay longer to help with more work or with rebuilding projects. Reed received his own news. He would be discharged in a few months and returned to Chicago to work in civilian life again. One evening, as they watched another Texas sunset smear orange and purple across the sky, he told Margaret he was leaving. She listened quietly, then said, “You will go home.

I will go home, but we will not be the same as when we left.” She touched her shoulder lightly. I will always carry this scar and also what happened here. The fields were bare now, the cotton gone. Soon the trains would return, this time heading east instead of west, and the question would be what, if anything, each of them would carry from Texas back into the broken world beyond the wire.

In February 1946, winter air lay cold and thin over Camp Swift. orders had come a transport of prisoners would leave for the journey back to Europe. Around 300 Germans from the camp were on the list. Margaret’s name was among them. On her last morning, the women lined up with small bundles, some clothes, a few letters, maybe a Bible or a photograph. The messaul smelled of oatmeal and coffee.

Trucks waited by the gate, engines ticking. The camp that had been their strange home for months was already turning back into just another army post. Reed met her near the infirmary. He held something in his hand, a small glass vial. Inside floated the twisted metal he had first seen under an operating room light. The surgeon kept this on a shelf, he said. I thought you should have it.

She turned the vial between her fingers. The glass felt cool. The metal chip was dark and ugly but clean. “What will I do with such a thing?” she asked. “Whatever you like,” he answered. “Keep it. Throw it away. Hide it. It is your story now.” She slipped it into her bag next to her papers. “I will keep it on my desk one day,” she said quietly.

To remember that an enemy’s knife saved me from my own army’s shell. They shook hands. It was a brief proper gesture watched by a whack nearby, but both of them felt the weight of it. Then she climbed into the truck with the others. The engine roared. Dust rose. The camp shrank behind them. The journey home reversed the one she had made before.

Trucks to trains, trains to a ship, the smell of cold smoke and salt air, the long gray ocean. By late 1946, most of the roughly 370,000 German PSWs held in the United States would be sent back across the Atlantic. They had come as conquerors, expecting to rule Europe for a thousand years. They left as students who had seen a different kind of power.

Full shelves, working lights, and hospitals that healed even the enemy. Back in H Highleberg, Margarite found a wounded city. Bridges were down, walls were blackened, but the university was rebuilding. Her father, still alive, worked with American occupation officials to reopen the chemistry department. With help from new programs and old contacts, she returned to her studies.

In one later letter to read, she wrote, “It seemed right that I work on medicines. After all, I am only here because someone had enough medicine to spare some for a prisoner.” By the early 1950s, West German factories were making millions of doses of antibiotics each year. New drugs that had first spread on Allied ships and in field hospitals now flowed from German labs, too.

At one of those lab benches stood a woman with a white coat and a scar on her shoulder. On her desk sat a small glass vial with a dark chip of metal inside. In 1952, she sent Reed a photograph of herself outside a rebuilt university building, degree in hand. Her note was short. Dear Thomas, I thought you would want to know I finished. I still have the fragment.

It reminds me that even very small pieces of metal and very small mercies can change the line of a whole life. Reed, back in Chicago, read the letter behind the counter of the pharmacy he now owned. The store smelled of chalk, alcohol, and paper. Shelves held rows of pills and powders. He showed the photo to his wife, then put the letter carefully into a box with others.

Years later, he told his grandchildren, “When you hear about the war, remember not only tanks and bombs. Remember also a woman with metal in her shoulder, and how we learned that the enemy was not always who we thought.” Time moved on. Germany and the United States, once deadly enemies, became allies. American money helped rebuild German cities. German scientists worked with American ones.

Old soldiers visited battlefields together. The big numbers filled history books. Billions of dollars in aid. Millions of houses rebuilt. Whole armies disbanded. But none of those pages mentioned the vial on Margarite’s desk. After she died in her 80s, her daughter sorted her papers. Among them, she found Reed’s letters and the glass vial.

She decided not to hide them in a drawer. Instead, she gave them to a small museum in H Highleberg that collected everyday stories of the war and recovery. Now, the fragment sits in a glass case. The tag under it is simple. Shell fragment removed from German prisoner Texas, 1945. Visitors walk past on quiet feet.

Many do not stop. They are drawn to bigger displays, maps, uniforms, photographs of ruined streets. But some pause. They lean close. They imagine the heat under the skin, the long train rides, the bright light of the operating room, the American hand offering help. A guide tells them the short version of the story.

a young woman, a hidden wound, an American medic, and a choice to trust that went against everything both had been taught. Some visitors nod and move on. Others stand a little longer, thinking about the strange truth that in a world of total war, a small act of mercy between enemies, could last longer than flags or speeches.

Their story never decided a battle or changed a border. But in the space between a captured German Clark and an injured American medic’s son, hatred gave way to something else. This wasn’t propaganda. It was reality. Lived day by day in a hot Texas camp and remembered for a lifetime. The vial of metal is still there catching the light.

It shows that even when nations shout in slogans, individuals can choose to listen in a different way. In the years after the war, both countries liked to tell clear stories. Good versus evil, victory versus defeat, freedom versus tyranny. Those stories were not all lies, but they were not the whole truth either.

The truth also lived in small, quiet places, in a camp clinic in Texas, in a hospital ward, in a glass vial on a desk in H Highleberg. Margarite and Thomas never changed the course of armies. But they did something harder. They let reality break through the pictures in their heads. She learned that the monsters could also be nurses and medics. He learned that the enemy could be a tired young woman who simply wanted to live.

In the end, the strongest weapon in that war was not metal at all, but the choice to see another person clearly.

News

A STREET GIRL begs: “Bury MY SISTER”, the UNDERCOVER MILLIONAIRE WIDOWER’S RESPONSE will shock you

A STREET GIRL begs: “Bury MY SISTER”, the UNDERCOVER MILLIONAIRE WIDOWER’S RESPONSE will shock you Sir, can you…

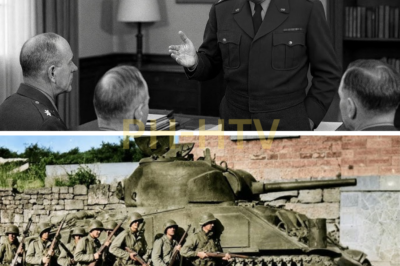

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Really Said When Patton Reached Bastogne Ahead of Everyone

What Eisenhower Really Said When Patton Reached Bastogne Ahead of Everyone December 1944 arrived over Western Europe with a cold…

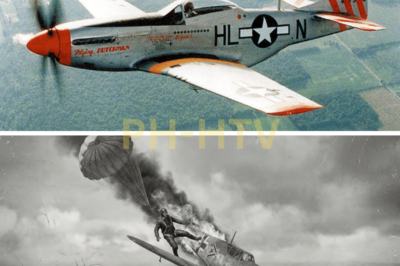

ch2-ha-German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds

German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds March 15, 1944,…

ch2-ha-By 1942, the Japanese Empire stood at the height of its power, controlling most of Southeast Asia and dreaming of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” But just three years later, everything collapsed.

World War II from Japan’s Perspective – Why Did Japan Lose? By 1942, the Japanese Empire controlled most of…

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours In the closing winter of 1944,…

ch2-ha-The Greatest Worst Spy Ever

The Greatest Worst Spy Ever There really is nothing quite like the element of surprise. When the Allied forces appeared over…

End of content

No more pages to load