How a U.S. Engineer’s “Bridge Wire Trick” Destroyed 7 Tanks in 5 Days

December 19th, 1944 0320 hours near Malmadi, Belgium. The frozen ground transmitted vibrations before the sound reached him. Sergeant David Dave Kowalsski of the second by Jushui Saint Engineer Combat Battalion pressed his ear against the ice crusted earth, counting the rhythmic tremors, tank tracks, multiple vehicles, Germans approaching from the northeast along the sunken farm road exactly as he calculated they would.

Kowalsski crawled backward from his observation position, moving carefully to avoid disturbing the thin layer of fresh snow that concealed his handiwork. 50 yards of steel bridge cable salvaged from a destroyed Bailey Bridge 3 kilometers away now lay buried under 4 in of frozen Belgian soil. The cable ran from his concealed position to a cluster of captured German teller mines positioned at precise intervals along the sunken roads narrow passage. This wasn’t standard military demolition.

This was improvisation born from desperation and mechanical aptitude. The cable designed to support 30 ton bridge sections had been repurposed as a remote detonation trigger through a mechanism Kowalsski had assembled from salvaged truck parts, door springs, and electrical components scavenged from a burnedout farmhouse.

At 0327, the first German tank, a Panther OSFG from the second SS Panzer Division, entered the kill zone through the pre-dawn darkness. Kowalsski could barely make out its silhouette, but he could hear the distinctive growl of the Maybach engine and the metallic clatter of tracks on frozen ground. Behind it, spaced at tactical intervals, came at least three more armored vehicles.

Kowalsski’s hands gripped the detonation mechanism he’d constructed, a simple labor system, almost primitive, but functional. When pulled, the lever would release tension on the bridge cable, which would pull firing pins from modified grenades buried with the mines, initiating a chain reaction that would detonate approximately 200 lb of explosives directly beneath the lead tank.

The mathematics were brutal, but precise. A Panther’s belly armor was only 16 mm thick, its weakest point. The teller mines, each containing 11 lbs of TNT, would create an upward blast that the tank’s armor couldn’t withstand. If Kowalsski’s calculations and positioning were correct, the Lead Panther would be destroyed instantly.

The following tanks, blocked by wreckage in the narrow road, would be trapped and vulnerable. At 0329, the Panthers front glasses crossed the invisible line Kowalsski had marked with stones during setup. He pulled the lever. The bridge cable buried 4 in deep and frozen in place, initially resisted for 3 seconds. That felt like hours. Nothing happened. Then the cable broke free from the ice.

The sudden tension release activating the firing mechanisms. The explosions came in rapid sequence, not simultaneous, but cascading as each grenade detonated and triggered nearby mines. The lead panther lifted 3 ft off the ground, its 44 ton mass thrown upward by the force of multiple mine detonations directly beneath its hull.

The tank’s belly armor shredded. Fuel tanks ruptured. Ammunition cooked off. The entire vehicle transformed into a fireball that lit the pre-dawn darkness like artificial sunrise. The following tanks, a second Panther and two Panzer FOs, halted immediately. The narrow sunken road provided no maneuvering room.

The burning wreckage of the lead tank blocked forward progress. The steep earthn banks on both sides prevented lateral movement. The German column was trapped exactly as Kowalsski had planned. But Kowalsski wasn’t finished. He’d positioned a second cable system targeting the rear of the column. As German crews began dismounting to assess the situation and clear the obstruction, Kowalsski triggered the second detonation.

More mines exploded beneath the rearmost Panzer for destroying its tracks and immobilizing it completely. The German column, now bracketed by destroyed vehicles in a narrow passage, represented a target. too valuable to abandon. Kowalsski fired a green flare, the pre-arranged signal. Within 90 seconds, American artillery began falling on the trapped tanks.

The barrage continued for 12 minutes, transforming the sunken road into a killing zone that German tank crews couldn’t escape. When dawn broke at 0715, five German armored vehicles lay destroyed or disabled in that narrow Belgian road. The lead panther completely destroyed by mine blasts. The second panther damaged by artillery and abandoned. Two panzer foes, one destroyed by mines, one immobilized by artillery hits.

A Stu Gi3 assault gun caught in the barrage burning with ammunition still cooking off. Five tanks destroyed through a technique that shouldn’t have worked according to conventional military engineering doctrine. Bridge cable wasn’t designed for demolition work. The remote detonation system was improvised from scrap.

The entire setup violated multiple technical manuals and safety regulations, but it had worked devastatingly well, achieving results that conventional mining operations couldn’t match. This was kill number one through five of what would become seven confirmed German armored vehicle destructions over the next 5 days.

A combat engineer using skills learned in his father’s Pittsburgh machine shop, combined with desperate innovation, was about to demonstrate that sometimes the most effective weapons emerge not from military procurement, but from individual ingenuity applied to desperate circumstances. The journey to this frozen Belgian road began 24 years earlier in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

David Kowalsski was born in 1920 to Polish immigrant parents who operated a small machine shop in the city’s industrial district. His father, Stannislaw Kowalsski, had immigrated from Kroof in 1912, bringing metalwork skills and mechanical aptitude that found ready employment in Pittsburgh’s booming steel industry.

Growing up in depression era Pittsburgh meant understanding machinery from childhood. By age 10, David could operate the shop’s lathe. By 14, he was helping his father with precision welding. By 18, he could diagnose mechanical problems that stumped trained machinists. This intuitive understanding of mechanics, stress, and materials would prove more valuable than any military training.

Kowalsski enlisted in the Army Corps of Engineers in March 1942, shortly after his 22nd birthday. His mechanical background and high school diploma made him ideal candidate for combat engineer training. The army needed men who could build bridges, clear obstacles, lay minefields, and conduct demolitions under fire.

Kowalsski possessed the technical foundation and equally important the calm temperament required for working with explosives. Basic engineer training at Fort Belvoir, Virginia provided formal education in military engineering principles, bridge construction, mine warfare, demolitions, obstacle clearing, field fortifications. Kowalsski excelled in all areas but showed particular aptitude for improvisation.

While other trainees followed textbook procedures, Kowalsski questioned why specific approaches were mandatory and whether alternatives might work better under different circumstances. This tendency to question doctrine concerned some instructors but impressed others.

Captain Robert Mitchell, commanding the advanced demolitions course, recognized Kowalsski’s potential in a March 1943 evaluation. Mitchell wrote, “Private Kowalsski demonstrates exceptional mechanical aptitude and creative problem-solving ability. He understands principles rather than just procedures, enabling him to adapt techniques to circumstances rather than rigidly following doctrine. recommend advanced training and potential NCO track.

Kowalsski shipped overseas in August 1943. Assigned to the second Baiju Xi Eati Engineer Combat Battalion supporting the first infantry division. The unit participated in the Sicily invasion, then the Italian campaign before transferring to England for D-Day preparation. Throughout this period, Kowalsski developed reputation as the soldier who could fix anything, build anything, or blow up anything given sufficient time and materials.

The Normandy invasion on June 6th, 1944 provided Kowalsski’s introduction to the challenge that would define his later innovations. German armor, particularly Tiger and Panther tanks, dominated the Bokeage fighting. American anti-tank weapons often proved inadequate. Bazooka teams achieved kills but took heavy casualties. Tank destroyers were effective but vulnerable.

Artillery could disable tanks but required extensive ammunition expenditure. Engineers meanwhile possessed demolitions expertise and explosives access but lacked effective methods for employing them against moving armor. Traditional mining worked only if enemy tanks obligingly drove over prepared positions.

Direct assault demolitions required suicidal courage and rarely succeeded. The gap between engineers demolition capability and practical anti-tank application seemed unbridgegable. Kowalsski began studying the problem during the hedro fighting in June and July 1944. He observed that German tanks, while formidable in direct combat, showed predictable movement patterns.

They used roads whenever possible to conserve fuel and preserve mechanical systems. They followed terrain that provided cover and concealment. They avoided obvious obstacles and suspected minefields. This predictability created opportunity. If you could anticipate where German tanks would travel and prepare positions along those routes, mining became feasible.

But the challenge was remote detonation. Conventional pressure fuse mines required tanks to drive directly over them. Command detonated mines required electrical firing systems that were complex, unreliable in wet conditions, and easily detected. The breakthrough came in September 1944 during the advance across France.

Kowalsski’s unit was assigned to repair a Bailey bridge destroyed by German demolitions. Bailey bridges, the modular portable bridges that enabled Allied river crossings, used steel cable assemblies for structural support. These cables woven from hightensile steel wire could support enormous loads and withstand tremendous tension. As Kowalsski examined damaged cable sections destined for salvage, an idea formed.

Cable was strong, flexible, and could transmit mechanical force over distance. If you buried cable running from concealed position to explosives in placement, then applied sudden tension or release to the cable. You could trigger detonation mechanically without electrical systems. The cable itself became the trigger mechanism.

The concept was simple, but implementation required solving multiple technical challenges. How to bury cable without it being detected. How to maintain cable tension under varied ground conditions. How to convert cable movement into reliable detonation trigger. How to position explosives for maximum effect against armored vehicles.

Kowalsski spent October and November 1944 developing solutions. He experimented with burial depth, finding that four to 6 in prevented detection while allowing cable to function. He designed tensioning systems using springs and counterweights salvaged from vehicles. He created firing mechanisms using modified grenade fuses that would detonate when pins were pulled by cable movement.

Most critically, he studied German tank tactics to identify predictable routes. Sunken roads common in Belgium and France forced vehicles into narrow passages where maneuver was impossible. Defiles between hills created natural choke points. Bridge approaches concentrated traffic onto predictable paths.

These locations became ideal for cable detonated ambushes. By December 1944, Kowalsski had refined his technique but lacked opportunity to employ it. The Allied advance had stalled along Germany’s border. Combat had evolved into static warfare that didn’t favor improvised demolitions. Then Hitler launched Operation Watch Amrin, the Arden’s offensive, and everything changed.

December 16th, 1944, the German attack began with over 200,000 troops and nearly 1,000 tanks. The assault achieved complete tactical surprise driving deep into American lines. The second by Johineer Combat Battalion found itself in the path of the second SS Panzer Division’s advance toward Malmade and ultimately the Muse River.

Engineers designed to support advancing troops suddenly face defensive combat against armor they weren’t equipped to fight. But the desperate circumstances created exactly the conditions where Kowalsski’s cable technique could work. German tanks were advancing along predictable routes. Time existed to prepare positions.

Materials were available. Permission to try unconventional methods was implicit given the crisis. On December 18th, Kowalsski requested authorization from his company commander, Captain James Sullivan, to implement experimental anti-tank demolitions along German approach routes.

Sullivan facing impossible tactical situation with inadequate resources. Approved immediately. Use whatever you can salvage. Stop those tanks by any means necessary. You’ve got 48 hours before they overrun our position. Kowalsski and four volunteers, Corporal Mike Chen, Private Firstclass Tommy O’Brien, Private Joe Martinez, and Private Bill Henderson, began preparations immediately.

They salvaged 120 yards of bridge cable from a destroyed span. They gathered 60 termines from battalion stocks and captured German supplies. They collected grenades, wire, tools, and various mechanical components. Working through December 18th night, the team prepared two ambush positions along routes intelligence indicated German armor would likely use.

The first position, the sunken road where the December 19th engagement would occur, required 18 hours of continuous work. They buried cable, positioned mines at calculated intervals, constructed firing mechanisms, and camouflaged everything beneath fresh snow. The second position, a narrow defile between two hills 3 km south, took another 8 hours. By December 19th dawn, both positions were ready.

The team withdrew to concealed observation posts and waited for German tanks to enter their carefully prepared kill zones. The December 19th engagement described in the opening exceeded Kowalsski’s expectations. Five German armored vehicles destroyed in a single action. The technique’s effectiveness was undeniable, but Kowalsski recognized that German forces would adapt.

The destroyed column would be reported. Route security would increase. Future cable detonated ambushes would be harder to prepare and execute. The December 19th afteraction report filed by Captain Sullivan documented unprecedented results.

Sergeant Kowalsski employed innovative cable actuated demolitions to destroy five enemy armored vehicles in single engagement. Technique utilized salvaged bridge cable as mechanical trigger for mine detonations, avoiding electrical firing systems limitations. Results suggest significant potential for engineer anti-tank operations. recommend immediate documentation and potential wider implementation, but there was no time for systematic documentation.

The German offensive continued. More armor was advancing. Kowalsski’s team had 72 hours of materials and energy remaining for additional operations. They needed to maximize impact before exhaustion or enemy adaptation ended their effectiveness. December 20th began with reconnaissance for new positions. Kowalsski identified a bridge approach where German armor would concentrate to cross a small river.

The bridge itself was damaged but repable and intelligence indicated German engineers were preparing to restore it for tank passage. If Kowalsski could position cable detonated mines near the bridge, approaching tanks would be channeled directly into the kill zone. Working through December 20th afternoon and evening, the team prepared the bridge ambush.

They positioned 20 teller mines along both approaches, connected by 40 yards of buried cable to a concealed firing position on a hillside 300 yd distant. The cable ran underground, invisible under snow, connecting to a firing mechanism Kowalsski had improved based on December 19th lessons learned. December 21st 0540 hours brought the expected German armor.

A column of three Panzer Warf from the 9inth SS Panzer Division approached the bridge, advancing cautiously due to obvious ambush potential. German infantry screened the armor, searching for mines and obstacles, but they were looking for electrical wires, not buried mechanical cable that transmitted no detectable signature. At 0612, the lead Panzer 4 reached the bridge approach.

Kowalsski waited for the second tank to enter the kill zone, maximizing casualties. At 0617, with two tanks fully committed to the narrow approach, and the third following, Kowalsski triggered the detonation. The bridge approach erupted. Multiple teller mines detonated beneath and beside the lead two panzers.

The lead tank’s tracks were destroyed, immobilizing it instantly. The second tank took direct hit beneath its hull, penetrating armor and igniting ammunition. The resulting explosion was catastrophic. The turret separating from the hull and flying 30 ft before crashing down. The third Panzer 4, seeing the destruction ahead, attempted to reverse, but the narrow approach and following vehicles prevented rapid withdrawal. American artillery pre-registered on the position and waiting for Kowalsski’s signal flare

began falling within 90 seconds. The third tank caught between mines ahead and artillery behind was disabled by near maces that destroyed its tracks. By 0700 hours, three more German tanks were destroyed or disabled. Total count, eight armored vehicles destroyed in two engagements using Kowalsski’s cable technique, but the team had exhausted most of their mine supplies.

Remaining materials would permit perhaps one or two more operations before they’d need resupply that wasn’t coming given the chaotic tactical situation. If you’re fascinated by the tactical innovations and engineering ingenuity that turned desperate situations into Allied victories during World War II, make sure to subscribe to our channel and hit the notification bell.

We bring you the untold stories of soldiers who achieved extraordinary results through creativity under pressure. Don’t miss our upcoming videos on the improvised weapons and tactics that changed history. December 21st afternoon brought critical decision point. Continue offensive operations with limited materials or preserve remaining resources for potential defensive use. Kowalsski argued for one final ambush.

The German offensive was beginning to stall. American reinforcements were arriving. One more successful engagement might contribute to tipping point where German advance collapsed. Captain Sullivan approved final operation but imposed conditions. Limited to materials on hand. No resupply available. Maximum 48 hours preparation time.

Withdrawal plan mandatory given likely German counteraction. Success metrics focused on maximum destruction rather than personal survival. These grim conditions reflected battlefield reality. The Arden’s fighting had devolved into desperate close quarters combat. Engineers were functioning as infantry. Casualties were mounting. Kowalsski’s team was exhausted, having worked nearly continuously for 72 hours.

But the opportunity to inflict additional damage on German armor justified the risk. December 22nd and 23rd were spent preparing the final ambush. Kowalsski selected a location where German retreat routes from the failed offensive would channel withdrawing armor. Intelligence indicated German forces were beginning fallback movements as American counterattacks intensified.

Withdrawing tanks, potentially damaged or low on fuel, would be vulnerable. The position was a narrow valley with steep sides, essentially a natural funnel. Kowalsski’s team positioned their remaining mines, approximately 30 teller mines and various improvised explosives along the valley floor.

Two cable systems were installed, one targeting the valley entrance, one targeting the exit, allowing bracketing of any column that entered. December 24th 0900 hours brought a withdrawing German column. mixed armor, including a Tiger 1, two Panthers, and several lighter vehicles. The column was moving rapidly, suggesting fuel concerns or tactical urgency.

German infantry security was minimal, indicating desperation or exhaustion. Kowalsski waited until the entire column entered the valley before triggering the entrance cable. Mines detonated beneath the lead vehicles, destroying a stoug to three and damaging a Panzer 4. Before the column could react, Kowalsski triggered the exit cable, destroying a halftrack and immobilizing a Panther.

The German column was trapped. The Tiger Buffers, the most dangerous vehicle, attempted to clear the obstacles through main gunfire and attempted to push wrecked vehicles aside, but the narrow valley prevented maneuvering. American artillery, again pre-registered and waiting, began systematic bombardment.

The artillery barrage lasted 40 minutes, expending over 200 rounds. When it ceased, two more German tanks were destroyed, including the Tiger, the FMuna, which took direct hit that penetrated its armor. The final count from December 24th. Two confirmed destroyed by Kowalsski’s mines. two destroyed by artillery. His ambush had trapped, multiple vehicles damaged and abandoned.

Kowalsski’s 5-day campaign December 19th through 24th had achieved total destruction or severe damage to seven German armored vehicles directly attributable to his cable detonated mine technique. Additional vehicles destroyed by artillery his ambushes enabled brought total impact to approximately 12 to 15 armored vehicles eliminated.

This represented significant tactical success for fiveman engineer team armed with improvised weapons. The afteraction analysis filed by battalion headquarters on December 27th documented the results with clinical precision. Sergeant Kowalsski’s innovative cable actuated mine technique achieved destruction of seven confirmed enemy armored vehicles with additional artillery kills enabled by his tactical positioning.

Technique demonstrated superior reliability compared to electrical firing systems, greater range than direct assault demolitions, and psychological impact through unpredictability. recommend formal documentation, potential training integration, and decoration consideration. But the human cost was also documented. Private Joe Martinez killed by German artillery during December 21st operation.

Private Bill Henderson severely wounded during December 24th engagement, evacuated with career-ending injuries. The remaining team members, Kowalsski, Chen, and O’Brien, were physically and psychologically exhausted from 5 days of continuous high-stress operations. The German reaction preserved in captured documents revealed the cable techniques psychological impact.

A December 26th intelligence summary from second SS Panzer Division headquarters stated, “American engineers employ unknown mind triggering system, possibly acoustic or radiocontrolled. Multiple armored columns destroyed by mines that detonated without vehicle contact or visible command wires. Conventional mine detection procedures ineffective. All routes must be considered compromised.

recommend engineer reconnaissance of all approach routes before armored advance. This German assessment, while technically incorrect about the trigger mechanism, validated Kowalsski’s approach. The enemy had developed paranoia about mine threats and was consuming precious time and resources on route reconnaissance.

This operational degradation slowing German movements and complicating their already failing offensive represented strategic impact beyond tactical vehicle kills. Before we continue with the lasting impact and legacy of this remarkable innovation, I want to ask you to take just two seconds to subscribe to our channel if you haven’t already.

These deep dives into forgotten engineering innovations and the soldiers who turned scrap into weapons take enormous research effort. Your subscription helps us continue bringing these stories to light. Hit that subscribe button and the notification bell.

The technical documentation of Kowalsski’s bridge cable technique compiled in January 1945 provided detailed methodology for replication. The document classified restricted due to tactical sensitivity outlined principles, materials, procedures, and limitations. Excerpt from Kowalsski’s technical manual. Cable actuated demolitions operate on mechanical force transmission over distance without electrical components.

Bridge cable designed for high tensil loads serves dual purpose as both structural burial element and force transmission medium. When buried at sufficient depth to avoid detection, but shallow enough to permit movement, cable can transmit pull force from remote position to trigger mechanisms at target location.

The manual specified optimal cable burial depth of 4 to 6 in, tension management using spring systems, firing mechanism construction using modified grenades or blasting caps, and positioning calculations for maximum effect against armor. It also emphasized limitations. Required preparation time of 12 to 24 hours per position, vulnerable to enemy engineer reconnaissance if setup detected.

Required predictable enemy movement along prepared routes. Weather dependency for ground conditions permitting cable burial. The Army Corps of Engineers evaluated the technique in February 1945 for potential standardization. Their assessment was mixed.

The technical review acknowledged effectiveness but identified scalability concerns. Few engineers possessed Kowalsski’s mechanical aptitude and improvisational skills. The technique required materials not always available. Setup time limited applicability to defensive operations where preparation time existed. Despite these limitations, the technique was incorporated into engineer training at Fort Belvoir as example of field expedient demolitions.

Students studied Kowalsski’s methodology not for exact replication, but for underlying principles of creative problem solving under resource constraints. The lesson emphasized thinking beyond doctrine when circumstances demanded innovation. Combat implementation of cable actuated demolitions varied across European theater.

Some engineer units successfully employed the technique against German armor during the Rine crossing operations. Others attempted it but achieved limited results due to unsuitable terrain or enemy countermeasures. Statistical analysis from March 1945 showed cable techniques achieved approximately 15 confirmed armored vehicle destructions beyond Kowalsski 7. Respectable but not revolutionary.

The broader impact was psychological and doctrinal rather than purely tactical. Kowalsski demonstrated that combat engineers could effectively engage armor using creativity and available materials. This realization influenced post-war engineer doctrine, expanding the role beyond traditional construction and obstacle missions to include direct anti-armour operations using improvised techniques.

David Kowalsski’s personal experience of the 5-day campaign was characterized by exhaustion, grief, and moral ambiguity. In later interviews, he described the operations with technical precision but emotional distance. We destroyed seven tanks, he stated in 1976 interview. But Joe Martinez died doing it. Bill Henderson lost his leg.

Was the trade-off worth it? Strategically, probably. Personally, I’m not sure any tactical success justifies losing friends. This moral complexity deepened when Kowalsski learned that German tank crews he’d killed were largely teenage conscripts manning equipment they barely understood in an offensive most German generals knew was doomed.

The Tiger I destroyed on December 24th was crewed by 16 and 17year-old boys, none surviving the artillery barrage. Kowalsski carried this knowledge for the rest of his life. Postwar, Kowalsski struggled with readjustment despite not seeing as much continuous combat as many veterans. The five days in December 1944 had concentrated intense stress, responsibility, and moral weight into brief period that left lasting impact.

He returned to Pittsburgh in April 1946, resumed work in his father’s machine shop, and tried to rebuild normal life. But readjustment proved difficult. Kowalsski experienced nightmares about cable tensions failing, mines not detonating or detonating prematurely and killing his team.

He startled at sudden sounds. He avoided discussing war experience even with family. The technical achievement of the cable technique brought no pride, only memory of Joe Martinez’s death and Bill Henderson’s screams as medics worked on his shattered leg. In 1949, Kowalsski enrolled in engineering program at Carnegie Tech, now Carnegie Melon University, using GI Bill benefits.

The structured academic environment provided focus that civilian work lacked. He graduated in 1953 with degree in mechanical engineering, found employment with Westinghouse Electric, and slowly developed life structure that accommodated rather than eliminated war trauma. Kowalsski married in 1955 to Katherine Walsh, an army nurse who served in European theater and understood combat trauma’s lasting effects without requiring detailed explanations.

They had three children and lived quietly in Pittsburgh suburb. Kowalsski’s military service was known to family but rarely discussed. His decorations, including bronze star with V device for valor, remained in drawer. Only in 1976 when Army Corps of Engineers historical office was documenting World War II engineering innovations did Kowalsski agree to extensive interview.

That interview preserved in Army archives revealed his technical thinking and moral reflection on the bridge cable technique. The cable worked because it was simple, Kowalsski explained. No batteries to fail, no electrical components to short out in wet conditions. no complex mechanisms to malfunction, just steel cable transmitting mechanical force. The Germans couldn’t detect it because they were looking for electrical signatures that weren’t there.

Simplicity was the weapon, not sophistication. The interviewer noted Kowalsski’s focus on technical aspects while avoiding discussion of casualties inflicted. Kowalsski responded bluntly. I can discuss engineering because that’s problem solving. I can’t discuss killing because there’s no solution.

Seven tanks destroyed means approximately 28 to 35 German tankers killed. Young men mostly. They died because I understood force transmission and they didn’t. That’s not heroism. That’s engineering applied to killing. This moral discomfort with being celebrated for essentially designing efficient killing methods characterized Kowalsski’s relationship with his wartime service.

He acknowledged tactical necessity while refusing to romanticize or minimize the human cost. The bridge cable technique was effective engineering and tragic necessity. Two truths that couldn’t be reconciled only carried. The technical legacy of Kowalsski’s innovation extended into surprising modern applications.

Mine warfare doctrine still includes mechanical triggering systems as backup to electronic detonation. Special operations forces use cablepull triggers for ambush detonations in environments where electrical systems are unreliable. The principle of simple mechanical force transmission remains relevant where sophisticated electronics are vulnerable or unavailable.

The Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center teaches expedient demolitions, including cable actuated triggers as part of their curriculum. Students learn Kowalsski’s technique not for exact replication, but as example of adapting materials to tactical requirements. The lesson emphasizes that engineering ingenuity can substitute for missing equipment when principles are understood rather than just procedures memorized.

Modern analysis of Kowalsski’s December 1944 operations emphasizes several factors beyond the cable technique itself. First, his mechanical aptitude enabled innovation that procedurally trained engineers couldn’t achieve. understanding stress, tension, and force transmission allowed improvisation that men following manuals couldn’t envision. Second, Kowalsski’s calm temperament under pressure permitted careful setup work while under time constraints and tactical threat.

Many technically skilled soldiers couldn’t maintain precision while facing immediate combat danger. Kowalsski’s ability to focus on technical details despite chaos proved as important as his mechanical knowledge. Third, team cohesion multiplied individual capability. Kowalsski couldn’t have prepared the ambush positions alone.

Chen, O’Brien, Martinez, and Henderson contributed skills and labor that made complex operations possible. Their trust in Kowalsski’s unconventional approach enabled effectiveness that skeptical team would have undermined. Fourth, tactical intelligence and terrain analysis determined success. The cable technique only worked because Kowalsski correctly predicted where German armor would travel and prepared positions accordingly. Technical capability without tactical understanding would have wasted materials and effort.

David Kowalsski died in 2004 at age 84 in Pittsburgh. His obituary mentioned his Army service and bronze star, but focused on his 40-year engineering career at Westinghouse and his family’s four children and nine grandchildren. Local veterans organization provided military funeral honors.

The rifle salute echoed across cemetery as his grandchildren, who knew him only as gentle grandfather, learned he’d been warrior. Among Kowalsski’s papers, family found detailed technical drawings of cable actuated firing mechanisms created for memory in 1990s for historical preservation. These drawings donated to Army Corps of Engineers Museum reveal sophistication that written descriptions couldn’t capture.

The precision of force calculations, the redundancy built into trigger mechanisms, the attention to failure analysis, all demonstrate engineering mindset applied rigorously to tactical problems. Also preserved were letters Kowalsski wrote but never sent to the families of German tank crews he’d killed. The letters discovered after his death expressed regret while acknowledging necessity.

I killed your son, husband, father because war demanded it. One letter stated, “He was doing his duty. I was doing mine.” Our duties conflicted and mine succeeded. This doesn’t make me right or him wrong. It makes us both victims of circumstances larger than individual choices. I’m sorry he died. I’m sorry I lived. I carry both truths. These unscent letters reveal psychological burden that many effective combat soldiers carry.

The actions were necessary within war’s context, but necessity doesn’t eliminate moral weight or human cost. Kowalsski understood both truths and refused to minimize either through rationalization. The seven German tanks destroyed between December 19th and 24th, 1944 are documented in Army and German military records.

Specific vehicles included December 19th, one Panther OSFG, one Panther OSFA, two Panzer 4s, one Stuge 3, all from second SS Panzer Division. December 21st, two Panzer refus, one from 9th SS Panzer Division. December 24th, one Tiger, Roar Heavy Tank, One Panther, AOSFG, both from units conducting fighting withdrawal from the failed Arden’s offensive.

Modern historical research, cross-referencing American and German records, confirms these destructions, though exact attribution between mine kills and artillery kills remains debated. What’s undisputed is that Kowalsski’s cable triggered ambushes created the tactical conditions that led to all seven confirmed destructions.

The bridge cable itself, the physical artifact that enabled Kowalsski’s innovation, represents interesting historical footnote. Bailey bridges used standardized components, including specific cable types. The cable Kowalsski salvaged and repurposed was British manufactured hightensile steel originally designed for structural support.

Its conversion into weapon trigger demonstrates how industrial materials when understood mechanically rather than just functionally can serve purposes beyond original design. Military historians studying Kowalsski’s operations note parallels with other improvised anti-tank methods. Soviet soldiers using Molotov cocktails, American infantrymen employing sticky bombs, British commandos using limpet mines, all represented improvisations born from inadequate official anti-tank weapons.

Kowalsski’s cable technique fit this pattern, but with engineering sophistication that exceeded most expedient methods. The psychological warfare dimension of Kowalsski’s operations deserves emphasis. The seven tanks destroyed represented direct tactical impact, but the broader effect, German paranoia about undetectable mines and resulting movement delays arguably exceeded the physical destruction.

German forces consumed valuable time and engineer resources on route reconnaissance that found nothing because there was nothing electrical to find. This operational degradation contributed to the Arden offensive failure more than seven destroyed tanks alone could have. In final assessment, David Kowalsski’s 5-day bridgecable campaign represents convergence of mechanical aptitude, tactical creativity, personal courage, and fortunate circumstances.

A combat engineer using skills learned in his father’s Pittsburgh machine shop, salvaged bridge cable and desperate innovation, achieved seven confirmed German tank destructions that conventional engineer doctrine said were impossible. The technique was elegant in simplicity. Bury cable connecting remote position to mines positioned where enemy tanks will travel.

Wait for tanks to enter kill zone. trigger mechanical detonation via cable pull, displace before counteraction. The execution required exceptional skill, careful planning, and courage to remain in position while tons of German armor approached on predictable schedules. But Kowalsski’s legacy transcends the kills and technique.

His story demonstrates that significant tactical advantage can emerge from understanding principles rather than just following procedures. That creativity matters more than resources. That simple solutions often outperform complex systems. That engineering ingenuity applied to tactical problems can achieve results sophisticated weapons cannot.

Most importantly, Kowalsski’s moral struggle with his success reminds us that effectiveness in war doesn’t eliminate human cost. Seven tanks destroyed meant approximately 30 German soldiers killed. Mostly teenagers conscripted into losing cause. Joe Martinez died. Bill Henderson lost his leg. These casualties, friendly and enemy, can’t be erased by tactical success or historical distance.

The bridge cable preserved in core of engineers museum alongside Kowalsski’s technical drawings and bronze star sits in display case with placard explaining the context and innovation. The placard concludes with Kowalsski’s words from his final interview before death. Engineering is about making things work.

War is about making things die. I made things die very efficiently for 5 days in December 1944. The efficiency doesn’t make me proud. The necessity doesn’t erase the cost. I did what war demanded. I’ve carried what it cost ever since. Those words provide fitting epitap for combat engineer who turned bridge cable into weapon.

David Kowolski innovated brilliantly, fought courageously and won tactically. But he also carried moral burden of efficient killing for 60 years. Never seeking absolution, never forgetting the human cost, never pretending necessity made it less tragic. The seven German tanks lie in Belgian fields, in German archives, in American afteraction reports.

David Kowalsski carried them in memory until his death. Both truths matter. Neither cancels the other. That’s the complete lesson of the bridge cable trick. Not just how it worked, but what it cost the man who made it work. Technical triumph and human burden, forever linked, forever carried.

News

ch2-ha-8 Tales of Pearl Harbor Heroics From the man who led the evacuation of USS Arizona to the fighter pilot who took to the skies in his pajamas, learn the stories of eight of the many servicemen who distinguished themselves on one of the darkest days in American military history.

1. Samuel Fuqua Missouri-born Samuel Fuqua had a front-row seat to the devastation at Pearl Harbor from aboard USS Arizona,…

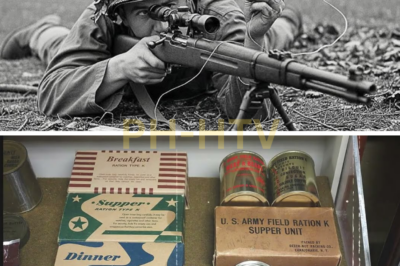

ch2-ha-How a U.S. Sniper’s “Soup Can Trick” Changed the Course of a Deadly Five-Day Standoff in WWII

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Soup Can Trick” Took Down 112 Japanese in 5 Days…. November 11th, 1943….

EVEN THREE NANNIES QUIT ON THE MILLIONAIRE’S BABY — UNTIL A BLACK MAID DID THE UNTHINKABLE

Even 3 Nannies Couldn’t Withstand the Millionaire Baby — Until the Black Maid Did the Unexpected Three professional nannies had…

MY HUSBAND’S FIVE-YEAR-OLD DAUGHTER WOULDN’T EAT AFTER MOVING IN — EVERY NIGHT SHE SAID “I’M NOT HUNGRY,” UNTIL I DISCOVERED WHAT HER REAL MOM TOLD HER

My husband’s five-year-old daughter had barely eaten since moving in with us. “I’m sorry, Mom… I’m not hungry,” she would…

“PROTECT THIS CHILD. HE IS YOUR KING,” THE UNKNOWN MAN TOLD THE FARM WOMAN — THEN DISAPPEARED INTO THE DARKNESS WITH NO EXPLANATION

“HIDE THAT CHILD HE’S THE FUTURE KING,” SAID THE MYSTERIOUS MAN AS HE HANDED THE BABY TO THE WOMAN Hide…

I OPENED MY HUSBAND’S CAR BOOT AND FOUND A STACK OF OBITUARY POSTERS — WITH MY FACE ON THEM AND TOMORROW’S DATE

I Wanted To Surprise My Husband In His Office By Hiding In The Car, But When I Saw Who Was…

End of content

No more pages to load