German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds

March 15, 1944, 20,000 feet above Berlin, the Faka Wolf 190 pilot from Hamburg saw the American fighter approaching and actually smiled. Another one of those new Mustangs the Americans were so proud of. Looked like a toy compared to his fighter. Sleek, yes, but almost delicate. The German had shot down 17 bombers and eight fighters.

He’d faced thunderbolts, lightnings, spitfires. This would be number nine. He rolled inverted, beginning his attack run. The American pilot from Ohio didn’t even change course, just kept boring straight in. Amateur move. The German lined up his shot. 400 yd, 300. His finger moved to the trigger. That’s when the American’s nose lit up like a thunderstorm.

Six streams of 50 caliber bullets converged into a wall of lead moving at 2800 ft per second. The Faula Wolf disintegrated. Not crashed, not burned, disintegrated. The pilot from Hamburg never knew what killed him. One second, he was lining up an easy kill. The next, his aircraft was confetti scattered across the German countryside.

The American pilot, Lieutenant James Morrison, barely felt the recoil through his control stick. He’d fired for exactly two and a half seconds, 200 rounds. The P-51D still had another thousand rounds ready to go. The North American P-51D Mustang didn’t look like a killer. That was the problem the Germans had. They’d gotten used to American fighters that looked the part.

The massive P47 Thunderbolt with its brutal radial engine. The twin boommed P38 Lightning that screamed danger from every angle. The Mustang looked almost British with its clean lines and liquid cooled engine. Some German pilots called it the pretty one. They stopped calling it that after March 1944. The truth was hidden in those graceful wings.

Six Browning A&M M250 caliber machine guns. three in each wing. Each gun could fire 800 rounds per minute. Together, they created a cone of destruction that could saw a bomber in half at 600 yardds, or turn a fighter into aluminum dust at 300.

The ammunition load was 400 rounds for the inboard guns, 270 for the middle and outer positions. 1,80 rounds total, enough for 15 to 18 seconds of sustained fire. Didn’t sound like much until you realized what 15 seconds meant in aerial combat. Lieutenant Colonel John Meyer understood. The squadron commander from Pennsylvania had been flying combat missions since 1943.

Started in thunderbolts, good aircraft, tough as a brick house, could take punishment that would kill anything else flying. But it drank fuel like a drunk sailor on shore leave and couldn’t escort bombers all the way to Berlin. The P-51D could. More importantly, it could hunt. April 8th, 1944. Meyer led his squadron 30 mi ahead of the bomber stream.

Standard procedure was to stay close, weave above the bombers, wait for the Germans to come to you. Meyer had different ideas. Find them first. Hit them while they’re forming up. Don’t let them get organized. His squadron found 60 Messesmmit 109s climbing to intercept altitude near Leipick. The Germans were in perfect attack formation, setting up for a head-on pass at the bomber stream. Meyer’s wingman was a kid from Texas named David White.

22 years old, had been working in his father’s hardware store when Pearl Harbor happened. Now he was 8 m above Germany, diving at 400 mph toward 60 enemy fighters. His mouth was so dry he couldn’t swallow. His hands were steady, though, had to be. At these speeds, the slightest tremor would throw your aim off by 50 yards. The Germans didn’t see them coming.

Sun at the Americans backs, approaching from the one angle the 109 pilots hadn’t checked. Meyer opened fire at 400 yd. The concentrated fire from 650s hit the lead messes like a sledgehammer. The plane’s left wing separated at the route, just tore clean off. The fighter snap rolled and fell, taking its pilot down in a spin he couldn’t recover from.

White picked his target, a 109 painted yellow on the nose. Squadron leader probably fired a 3-second burst, 450 rounds. The yellow nose exploded. The engine block, 70 lbs of steel and aluminum, ripped free and tumbled away. The rest of the fighter folded in half and fell. The German formation scattered. Training went out the window. Suddenly, 60 pilots were trying to figure out where the attack had come from, how many Americans were up there, whether to climb or dive.

In that confusion, Meyer’s squadron destroyed 17 German fighters in 4 minutes. The P-51D’s speed advantage meant they could hit, extend away, climb back to altitude, and hit again before the Germans could organize a response. Captain Donald Blake Lee from Ohio had been fighting Germans since 1941. Started with the Eagle Squadron, Americans flying for the RAF before the US entered the war.

He’d flown Spitfires, Thunderbolts, and now Mustangs. By spring 1944, he’d figured out something the Germans hadn’t adapted to yet. The P-51D’s gun convergence could be set to create different kill zones. Most pilots set their guns to converge at 300 yards. All six streams of bullets meeting at a single point. Blakesley set his differently.

Inboard guns at 250 yards, middle guns at 300, outboard at 350. Created a wall of lead that something had to fly through. Couldn’t miss. May 12th, 1944. Blakesley caught a Yunker’s 88 bomber trying to sneak home at treetop level near Frankfurt. The German pilot was good, jinxing left and right, using every valley and hill for cover. Didn’t matter.

At 200 yd, Blakesley triggered a 4-se secondond burst. 600 rounds. The Junker’s tail section separated first, then the right wing, then the left engine exploded. The bomber cartwheeled into a wheat field. Total flight time from first hit to impact, 3 seconds. The mathematics of destruction were simple.

Each 50 caliber bullet weighed 46 g and left the barrel at 2800 ft per second. At 300 yd, it still carried enough energy to punch through an inch of steel. A 1second burst from all six guns put 80 bullets in the air. 2 seconds, 160. The bullets didn’t just make holes. The hydraulic shock of impact could shatter aluminum structures 3 ft away from the actual strike. Hit a fuel tank and the hydrostatic pressure would split it open like a watermelon even if the bullet passed clean through.

Lieutenant Robert Johnson from Oklahoma had been a mechanic before the war. Understood machines. Understood what those 650s could do to an aircraft’s systems. He’d calculated it once. A two-cond burst put 160 bullets into a space about 8 ft in diameter at 300 yards. No aircraft flying had more than 3 ft of critical components.

Engine, pilot, fuel controls that could survive that kind of damage density. You didn’t have to be a perfect shot, just good enough. June 6th, 1944. Dday. Johnson’s squadron flew three missions, dawn to dusk. The Germans threw everything they had into the air. Johnson shot down two Messers 109’s and a Faky Wolf 190 in a single hour over Normandy.

The first 109 he caught climbing. One and a half second burst into the belly as it passed below him. The pilot never saw him. Engine oil covered Johnson’s windscreen as he flew through the debris. The second tried to turn with him. Fatal mistake. The P-51D could turn inside a 109 at high speed. Johnson pulled lead and fired. Two seconds.

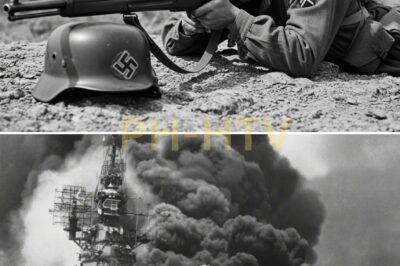

The 109’s cockpit disappeared in a shower of glass and aluminum. The fuckwolf tried to run, diving for the deck. Johnson followed him down, waited until the German had to pull up to avoid trees, fired just as the Germans wings took the strain of the pull out. The combined stress of G-forces and bullet impacts tore both wings off simultaneously. The German pilots weren’t cowards and they weren’t poorly trained.

By 1944, the Luftwaffa had some of the most experienced combat pilots in history. Men with hundreds of combat missions, dozens of kills. But experience against thunderbolts and lightnings didn’t translate to fighting P-51Ds. The Mustang was faster than anything they’d faced, could turn better than anything that fast should be able to turn, and carried enough ammunition to engage multiple targets.

Major Guorg Peter Eer had 96 kills when he encountered P-51Ds for the first time on July 7th, 1944. He’d shot down 17 4ine bombers, 12 Thunderbolts, eight lightnings. He knew American tactics, knew their weaknesses. The Thunderbolts couldn’t pursue if you dove away. They’d compress and lose control.

The Lightnings couldn’t turn with you at low altitude. The new Mustangs were different. Eder led six Messid 109s against four P-51Ds escorting bombers near Munich. Should have been easy. Six versus four experienced pilots fighting over friendly territory. The American flight leader was Captain Fred Christensen from Colorado.

Son of Danish immigrants had wanted to be an engineer before the war. Now he was engineering death at 25,000 ft. He saw the Germans coming up from below. The classic approach to attack bombers. Let them come. Waited until they committed to their climb, then rolled inverted and dove. The closure rate was over 600 mph. The Germans couldn’t abort their attack run without exposing their bellies.

Christensen opened fire at 500 yd, long range, but he had ammunition to spare. Walked his tracers into the lead 109. The German pilot, probably Eater himself, tried to roll away. Too late. 450 bullets found their mark in a 3second burst. The 109 came apart in stages. First the canopy, then the tail, then the wings folded backward, and the fuselage tumbled like a thrown brick.

Ader managed to bail out, but his parachute was torn by debris. He fell 20,000 ft. The remaining Germans scattered. Christensen’s wingman, Lieutenant Paul Kendall from Michigan, chased one down in a power dive that reached 450 mph. The German tried to pull out at 3,000 ft. Blacked out from the G-forces, Kendall put a two-cond burst into the unconscious pilot’s aircraft.

The 109 flew straight into the ground at 400 mph, made a crater 30 ft wide. The psychological effect was as devastating as the physical. German pilots who had felt confident engaging American fighters suddenly found themselves outmatched. The Luftwaffers started changing tactics, avoiding engagement unless they had overwhelming numerical superiority. Didn’t matter.

The P-51Ds had the range to hunt them wherever they tried to form up. Lieutenant Urban Drew from Detroit proved this on October 7th, 1944. Leading a flight of eight Mustangs, he found two German jet fighters, Messersmidt 262s, preparing to take off from an airfield near Osnibbrook.

The jets were faster than anything in the sky once airborne, but vulnerable during takeoff. Drew dove from 15,000 ft, reached 450 mph in the dive. The German jet pilot saw him coming, tried to abort the takeoff, too late. Drew opened fire at 600 yards, kept firing as he closed. 4 seconds, 600 rounds. The jet exploded on the runway. The second jet had just lifted off, gear still down.

Drew’s wingman, Lieutenant James Woods from Georgia, caught it at 50 ft altitude, 3se secondond burst. The jet cartwheeled into the forest beyond the airfield. The Germans tried everything. They armored their fighters, added extra guns, developed new tactics. Nothing worked. The P-51D’s combination of speed, range, and firepower made it the apex predator of European skies.

By late 1944, Luftwaffa pilots had a saying, “If you see a silver fighter, it’s American. If you see no fighters, it’s the RAF. If you see nothing at all, it’s a Mustang about to kill you.” Captain Ray Wetmore from California experienced the Mustang’s devastating firepower firsthand on November 27th, 1944.

Leading a patrol near Frankfurt, he bounced 12 Faka Wolf 190s, escorting a reconnaissance jet. The Germans were flying in perfect formation, textbook defensive positioning. Wet Moore’s flight of four Mustangs hit them from above and behind. In 45 seconds, eight German fighters were destroyed. Wetmore personally accounted for three, firing less than 5 seconds total. 650 rounds. Three aircraft destroyed.

The math was brutal in its simplicity. His first target never knew what hit him. Wetmore approached from the 6:00 high position. The Faka Wolf’s blind spot. Two second burst at 300 yd. The German fighter’s tail separated completely, the fuselage tumbling forward while the tail section fluttered down like a dropped piece of paper.

The pilot tried to bail out, but was unconscious or dead. His body fell free when the canopy opened, but the parachute never deployed. The second Faka Wolf saw Wetmore coming, tried to execute a split S to escape. The maneuver would have worked against a thunderbolt, which couldn’t follow without compressing. The P-51D followed him down easily. Wetmore fired a 1-second burst as the German pulled out of his dive.

Just 80 rounds, but perfectly placed. Caught the Faulk Wolf’s engine block. The massive BMW radial engine literally fell out of the airplane. The rest of the fighter suddenly, without its heaviest component, pitched up violently and stalled. The pilot bailed out successfully, but was captured as soon as he landed. The third kill was almost accidental.

Wetmore was climbing back to altitude when a faul wolf flew directly across his gunsite. The German pilot apparently focused on escaping another Mustang. Wetmore fired reflexively a second and a half burst. The concentrated fire cut the German fighter in half just behind the cockpit. The forward section with the pilot still inside fell straight down. The tail section spun like a maple seed. December 23rd, 1944.

The Battle of the Bulge was raging below. Every German fighter that could fly was in the air trying to support the ground offensive. Lieutenant Colonel John Landers from Texas led 48 P-51Ds on a fighter sweep ahead of the bomber stream. They found over a 100 German fighters forming up near Coblins. Mix of everything.

Messers 109s, Faula Wolf Wonder 190s, even some older 110 twin engine fighters the Germans had pulled from training units. What followed was later called the Cobblins Turkey shoot. In 20 minutes of combat, Landers group claimed 37 German aircraft destroyed. Landers himself got three, but the real story was his ammunition management.

1880 rounds total. Landers used them like a surgeon, short controlled bursts, never more than two seconds. By the time he turned for home, he’d fired 17 bursts, destroyed three aircraft, damaged two others, and still had 300 rounds remaining. That was the P-51D difference, enough ammunition to be selective to wait for the perfect shot to engage multiple targets.

The young lieutenant from Nebraska flying Lander’s Wing was David Hooker, 23 years old on his fifth mission. Still scared enough that he’d thrown up before takeoff. When the combat started, training took over, found himself behind a Messor Schmidt 110. The big twin engine fighter trying desperately to turn away. The 110 was obsolete, too slow, turned like a transport. Hooker put his gunsight on the left engine, fired a two-cond burst.

The engine exploded, wing folded. The big fighter tumbled out of control. Hooker shifted to another target so smoothly he surprised himself. Faka Wolf 190 diving away, led him perfectly, fired 3 seconds. The German fighter came apart like it had been unzipped, just fell to pieces in midair. The killing was becoming mechanical, systematic. The P-51D pilots developed a rhythm.

Spot, approach, fire, assess, extend, repeat. The 650s made it almost too easy. Captain William Wisner from Iowa described it later. It wasn’t like the movies. No long dog fights, no chasing through clouds. You bounced them, fired for two or three seconds, and they were gone. Either dead or running.

The guns did all the work. January 14th, 1945. Captain Gordon Graham from North Carolina demonstrated just how devastating those guns could be. Escorting bombers to Magnabberg. His flight encountered a rare sight. A formation of 30 Yunkers, 87 Stooka dive bombers heading east, probably being relocated away from the advancing allies.

The Stookas were obsolete, slow, practically defenseless against modern fighters. They were escorted by just four messes 109s. Graham’s flight of eight Mustangs destroyed all 30 Stookas in less than four minutes. Graham personally accounted for seven. The slowmoving dive bombers couldn’t evade, couldn’t run, couldn’t fight back effectively.

Graham would slide in behind one, fire a 1- second burst, watch it catch fire, or come apart, then shift to the next target. 80 rounds per kill. By the time the slaughter was over, the sky was full of falling debris and parachutes. The four escorting 109s had fled immediately, knowing they couldn’t protect their charges against 8 P51Ds. The mechanical sympathy every pilot felt for another airman was overridden by the mathematics of war.

Those stookas would have been used against Allied ground troops. Each one destroyed saved American lives. The 650s made the calculation simple. A two-cond burst, 300 rounds, one less threat to the boys on the ground. Graham felt sick afterward, but would do it again the next day and did. Lieutenant Robert Powell from Arkansas had been a school teacher before the war. Taught math and science to farm kids who’d probably never leave the county.

Now he was teaching German pilots a different lesson. February 3rd, 1945, near Brunswick, Powell’s flight jumped 15 Messeshmmit 109’s attacking stragglers from a bomber formation. The Germans had separated a wounded B17 from the herd. Were taking turns making firing passes. The bomber’s tail gunner was dead.

Waste gunners out of ammunition. Easy meat. Powell dove from 22,000 ft. Built up speed to 450 mph. The German flight leader was so focused on the bomber, he never saw Powell coming. Powell opened fire at 400 yd, kept firing as he closed. 4 seconds, 600 rounds. The 109 didn’t just fall. It disintegrated. The engine separated and fell independently. Both wings folded back and tore off.

The cockpit section tumbled free. The tail fluttered down like a leaf. five separate pieces where an airplane had been. Powell’s wingman, Lieutenant James Hart from Tennessee, caught another 109 as it pulled up from its attack run. The German pilot saw him coming, tried to execute a barrel roll defense. Might have worked against guns with less coverage.

Hart simply held the trigger down and let the German fly through his stream of fire. Three and a half seconds, 500 rounds. The 109 emerged from the other side of the barrel roll, missing most of its left wing and all of its tail. The pilot bailed out immediately. The bomber crew watched in amazement as the P-51Ds carved through the German formation.

In 90 seconds, 12 of the 15 German fighters were falling in flames. The remaining three ran for their lives, diving for the deck and disappearing into cloud cover. The bomber limped home, its crew alive because 650 caliber guns in each Mustang could throw so much lead that missing was almost impossible. March 2nd, 1945. The war in Europe had two months left. The Luftwaffa was dying, but dying hard.

Major James Howard from Minnesota led the last major fighter sweep over Berlin. Found the remnants of Yagdashwatter 7, Germany’s first alljet fighter unit. The Messmmet 262s were revolutionary, faster than any propeller aircraft, heavily armed with 430 mm cannons. In theory, they should have swept P-51Ds from the sky.

Theory met reality at 20,000 ft. The jets were faster in level flight, but couldn’t turn with the Mustangs. More critically, their cannons fired slowly, 60 rounds per minute, compared to the 50 calibers 800. Howard caught a 262 in a climbing turn, a maneuver that bled off the jet’s speed advantage. The German pilot realized his mistake, tried to dive away. Howard was already firing.

2 seconds, 240 rounds. The jet’s right engine exploded. Asymmetric thrust sent it into an uncontrollable spin. The pilot ejected, but his parachute tangled in the spinning wreckage. He fell with his aircraft. Lieutenant Charles Weaver from Pennsylvania had spent three years training to be a pilot.

Washed out twice, brought back because they needed bodies and cockpits. Not a natural flyer, had to think about every move, but he could shoot. Growing up hunting squirrels with a 22 taught him about lead and deflection. At 15,000 ft over Desau, he proved that skill was enough. A Messormid 262 flashed past him. Speed difference must have been 200 mph. Impossible shot for most pilots. Weaver calculated the lead instantly.

Not consciously, just knew where to put the gun sight. Fired a 4-se secondond burst into empty air. The jet flew right into it. 600 rounds formed a wall in space. The 262 hit that wall at 500 mph. The impacts were so rapid it looked like the jet had flown into a solid barrier. The nose section separated. Both engines exploded, the wings folded backward.

The pilot never had a chance to eject. By April 1945, German pilots were avoiding combat with P-51Ds unless they had no choice. Didn’t matter. The Mustangs had the range to find them wherever they hid. Lieutenant William Bruce from Oregon caught 12 FWolf 190s trying to relocate from Prague to Bavaria, flying at treetop height to avoid radar.

Bruce’s flight of four Mustangs followed them for 20 m, waiting for the perfect moment. When the German formation had to climb to clear a rgeline, Bruce attacked. The concentrated fire from four P-51Ds, 2450 caliber guns firing simultaneously, was apocalyptic. In the first pass, six German fighters were destroyed. Bruce personally accounted for two, firing a total of 3 seconds.

400 rounds, two aircraft destroyed. His wingman, Lieutenant Harold Brown from Maine, destroyed two more with a single long burst that caught them flying in formation. 5 seconds, 700 rounds. Two fighters turned to scrap metal. The remaining Germans scattered in all directions. Bruce chased one into a valley, following him through turns that pulled six G’s.

The German pilot was good, using every hill and tree line for cover. Didn’t matter. At 200 yards, Bruce fired a two-cond burst. The concentrated fire cut through the Faky Wolf’s tail section like a saw. The fighter pitched straight up, stalled, fell backward into a mountain side. April 16th, 1945, Lieutenant Wayne Bolar from Kansas recorded the last significant air combat of the European War.

Leading a patrol near Reaganburg, he encountered four Messers 109s attacking a reconnaissance P38. The Germans had the Lightning boxed in, taking turns, making passes. The P38’s left engine was burning, right engine failing. The pilot was wounded, trying to make it to Allied lines. Bolafar hit the Germans from above at full throttle. 450 mph in a 60° dive.

The lead 109 never knew what killed him. Bolafar opened fire at 300 yards. 1 and a half second burst. The concentrated fire struck the German fighter just behind the cockpit. The fuselage broke in half. The engine and forward section fell straight down while the tail and wings tumbled separately. The other Germans broke off immediately. Recognizing the distinctive sound of 650s firing.

Too late for one. Bolafar’s wingman, Lieutenant Robert Dickerson from Texas, caught a 109 as it rolled inverted to dive away. Two second burst into its belly. The fighter exploded. Just came apart in a ball of fire and aluminum. The remaining two Germans disappeared into clouds and were never seen again. The wounded P38 pilot made it home.

The numbers told the story. By war’s end, P-51D pilots had destroyed over 5,000 enemy aircraft in air-to-air combat. The 650 caliber guns had fired millions of rounds. Each bullet a potential death sentence for German aircraft. The mathematical certainty of it was terrifying.

At optimal range, a 2- second burst put 240 bullets into a space smaller than a garage door. No aircraft built could survive that concentration of firepower. Major Theodore Chandler from Maryland flew his last mission on May 7th, 1945, the day before Germany surrendered. Leading a patrol over Czechoslovakia, he encountered two Faky Wolf 190s whose pilots apparently hadn’t heard the war was ending. Or maybe they had, and wanted one last fight.

They attacked Chandler’s formation from above, using the sun for cover. Old tactics that might have worked in 1943. Chandler’s wingmen spotted them first called the break. The P-51Ds turned into the attack, forcing the Germans to overshoot. Suddenly, the hunters were the hunted. Chandler got behind one, fired a careful two-c burst at 300 yd.

The fuckwolf’s engine exploded, showering oil and parts across the sky. The pilot bailed out immediately. The second German tried to run, diving for the deck at full power. Chandler followed him down, waited until he had to pull out to avoid terrain, fired just as the G-forces peaked. One and a half seconds.

The combined stress of the pull out and bullet impacts tore the fighter’s wings off. It cartwheelled into a field. They were the last aircraft Chandler would destroy. By the next morning, the war in Europe was over. The P-51Ds had won air superiority through simple mathematics. More range, more speed, more ammunition, more kills.

The 650 caliber guns had been the deciding factor. German pilots who had laughed at the pretty American fighter had learned the hardest lesson of aerial combat. Beauty could kill, especially when it carried 1880 rounds of 50 caliber death. The pilots came home to a different world.

Captain Fred Christensen went back to Colorado, finished his engineering degree, spent 40 years building bridges, never talked about the 22 German aircraft he destroyed. Lieutenant David White returned to the hardware store in Texas. Customers buying hammers and nails never knew he’d once fired 600 rounds into a messmitt at 20,000 ft.

Major John Meyer stayed in the Air Force, rose to fourstar general, but said the most intense moments of his life were those 3second bursts over Germany. Some struggled with what they’d done. Lieutenant Robert Powell went back to teaching, but couldn’t forget the mathematics of killing. 240 rounds in 2 seconds, one aircraft destroyed, one pilot dead.

He’d killed 17 men in 8 months. The math was simple. Living with it wasn’t. He died in 1962, never having spoken about the war to his family. Others found peace in purpose. Captain William Wisner from Iowa became a test pilot, pushed experimental aircraft to their limits, said it was his way of honoring the German pilots he’d killed.

They’d died for aviation. He’d live for it. He flew until age 70, died in his sleep at 91, his log book showing 12,000 hours of flight time. The last entry was the day before he died. Lieutenant Urban Drew, who had destroyed the jets on the runway, became a commercial airline pilot.

flew DC3s, then 707s, then 747s, carried millions of passengers safely across the Atlantic, the same route he’d flown in 1944, hunting German fighters, said every landing was a gift to the men who hadn’t made it home. Retired in 1985 with a perfect safety record.

The machine that made it all possible, the P-51D Mustang flew on in different roles. Some became racers, setting speed records that stood for decades. Others flew as civilian transports in remote areas. A few survived as museum pieces, carefully maintained reminders of when 650 caliber guns could change history. The distinctive whistle of the Merlin engine and the hammering sound of 650s firing lived on only in recordings and memories. By the 1990s, most of the pilots were gone.

Lieutenant James Morrison, who had disintegrated that first Faka Wolf, died in 1994. His grandson found his log book in the attic, detailed accounts of 47 combat missions, 15 aircraft destroyed, all recorded in neat handwriting, like grocery lists. 2 seconds here, 3 seconds there. Another German fighter removed from the war. The mathematical precision of it was chilling.

Major Gordon Graham, who had destroyed the 30 Stookas, lived until 2003. Near the end, dementia took most of his memories, but he could still recite the firing sequence for 650 caliber guns. Could still calculate ammunition expenditure, 240 rounds in 2 seconds, 605. His hands would move like he was flying whenever he heard aircraft overhead. His family thought it was random movement.

It was actually perfect deflection shooting. 70 years of muscle memory. The last pilot from the 357th Fighter Group, Captain Harrison Toroff, died in 2016 at 95. He destroyed five German aircraft, all with less than 10 seconds of total firing time, 1,500 rounds to become an ace.

He kept a single 50 caliber bullet on his desk until the day he died. Said it reminded him that small things could change the world. 240 of them in two seconds could certainly change someone’s world permanently. The German pilots who survived had their own memories. Hans Dortonman, who had 20 victories before encountering P-51Ds, survived the war and lived until 1973.

He wrote once about facing the American fighters. You knew from the sound. Six guns firing together made a noise like tearing cloth, but amplified a thousand times. If you heard it, you were already dead or about to be. We learned to fear that sound more than anything else in the war.

Adolf Galland, the Luftwafa general who had laughed when he first saw the P-51D specifications, admitted after the war that the 650 caliber guns had been decisive. We expected cannon like the British used fewer shots but bigger impact. The Americans chose volume over size. Six streams of bullets that created a wall of death.

You couldn’t fly through it, around it, or survive it. They had engineered the perfect killing solution. The mathematics remained constant through all the memories and memoirs. Six guns, 800 rounds per minute each, 80 rounds per second combined, 240 rounds in 3 seconds, enough to destroy any aircraft flying in World War II.

The German pilots who had laughed at the P-51D’s appearance learned that in aerial combat, as in all combat, the only beauty that mattered was lethality. And nothing was more beautiful than 650 calibers, converting 1880 rounds into destroyed enemy aircraft in 15 to 18 seconds of sustained fire. Today, only a few dozen P-51Ds still fly.

At air shows, they demonstrate their grace and speed, but never their firepower. The 650 caliber guns are silent, permanently disabled or removed entirely. Crowds watch them pass overhead. Hear the Merlin engines distinctive sound. See the elegant lines that once fooled German pilots into fatal underestimation. They don’t hear what the German pilots learn to fear.

That tearing cloth sound of six guns firing. 240 rounds converging on a single point in space. The mathematical certainty of destruction delivered at 2800 ft per second. The pilots are nearly all gone now. Their children and grandchildren find foot lockers in atticss full of black and white photographs.

Young men standing next to P-51Ds trying to look casual about sitting on 1880 rounds of ammunition and 61 ft of concentrated death. They were boys really 22 23 years old handed the most effective fighter aircraft ever built and told to use it. They did. The last surviving P-51D pilot from the European theater died in 2019.

Colonel Clarence Anderson, 97 years old, 16 and a half victories. His last words to his son were about ammunition conservation. Never more than 3 seconds, boy. 3 seconds is all you need if you do it right. His hands moved one last time in the motion of triggering guns. 240 rounds in 2 seconds. The mathematics of survival at 25,000 ft. The equation that won the air war.

The German pilots who laughed at the P-51D in early 1944 had stopped laughing by May 1945. Those who survived never forgot the lesson written in 50 caliber bullets across European skies. Appearance meant nothing. Firepower meant everything and six guns firing 1,200 rounds in 15 seconds meant death.

The pretty American fighter with its elegant lines and liquid cooled engine had taught them the hardest truth of aerial combat. Beauty could kill, especially when it carried enough ammunition to destroy a squadron. The war ended 79 years ago. The last P-51D rolled off the production line in 1946. The pilots who flew them are gone, but the mathematics remain. 6 * 800 equals 4800 rounds per minute.

80 rounds per second. 240 rounds in 3 seconds. Enough firepower to turn any aircraft into aluminum confetti at 300 yards. The German pilots who laughed learned this equation the hard way. Those who survived never forgot it. Those who didn’t became part of the statistics. 5,000 enemy aircraft destroyed, millions of rounds fired.

each burst a calculated delivery of death at 2800 f feet per second. The P-51D Mustang remains the most successful fighter aircraft in history, measured by its impact on the war’s outcome. The 650 caliber guns were its voice, speaking a language every fighter pilot understood regardless of nationality. When they spoke, aircraft died.

It was that simple. The German pilots stopped laughing when they learned to recognize that voice. By then, for many, it was too late. They’d already heard the sound of 650s firing 240 rounds in 2 seconds. The last sound too many of them ever heard.

Thanks for joining us on this journey through one of history’s incredible survival stories. If you found it compelling, give it a like and share it with someone who appreciates these tales of courage. And don’t forget to subscribe for more.

News

ch2-ha-By 1942, the Japanese Empire stood at the height of its power, controlling most of Southeast Asia and dreaming of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” But just three years later, everything collapsed.

World War II from Japan’s Perspective – Why Did Japan Lose? By 1942, the Japanese Empire controlled most of…

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours In the closing winter of 1944,…

ch2-ha-The Greatest Worst Spy Ever

The Greatest Worst Spy Ever There really is nothing quite like the element of surprise. When the Allied forces appeared over…

ch2-ha-When Winter Becomes a Death Trap: Manstein’s Horrific Counterattack at Kharkov – WW2 Documentary

When Winter Becomes a Death Trap: Manstein’s Horrific Counterattack at Kharkov – WW2 Documentary The year was 1943. The…

ch2-ha-How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms April 1st,…

ch2-ha-The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

The other Allied commanders thought he was either lying or had lost his mind. The Germans were laughing, too. Hitler’s…

End of content

No more pages to load