World War II from Japan’s Perspective – Why Did Japan Lose?

By 1942, the Japanese Empire controlled most of Southeast Asia. It had managed to drive out the old European empires from their former colonies and was just one step away from complete domination of Asia. However, over the next 3 years, Japan would not only lose all its conquests, but ultimately surrender itself. Let’s look at the Second World War from Japan’s point of view.

By 1937, Japan already controlled Manuria and several Chinese provinces. But now it was ready to go further and begin a full-scale invasion. Japan sought to expel the European colonial empires from Asia and unite the region into the Greater East Asia co-rossperity sphere. Although this project would only be officially announced in 1940, Japan had begun implementing it much earlier.

For before it could challenge the European powers, it needed resources and influence. From the Japanese perspective, this was not merely a war of conquest. It was a mission of destiny. For decades, Japan had watched how the Western powers dominated Asia, enslaving nations under colonial rule. Britain controlled India, Burma, and Malaya. France ruled into China.

The Netherlands possessed the rich islands of Indonesia. And the United States governed the Philippines. Surrounded by western empires, Japan saw itself as the only Asian power strong enough to stand up to the west. But this ambition had deep roots. Since the Maji restoration of 1868, Japan had transformed from a feudal island nation into a modern industrial state.

The leaders of the new Japan looked to Europe, learning from its science, technology, and military organization. In only a few decades, Japan built railways, factories, steelworks, and a powerful navy. It won wars against China in 1895 and Russia in 1905, shocking the world. For the first time, an Asian nation had defeated a major European power. This victory gave Japan not only pride but also a sense of divine purpose, a belief that it was destined to lead Asia into a new age.

However, Japan’s rise was limited by geography and resources. The islands lacked oil, coal, iron, and other materials essential for industry. As Japan’s economy and military grew, its hunger for resources became desperate. The great powers controlled access to these materials, especially oil, which Japan imported mainly from the United States and the Dutch East Indies. Without them, the Japanese war machine would grind to a halt.

In the 1930s, the world was changing rapidly. The Great Depression had shaken the global economy. In Europe, fascism was rising. Germany and Italy challenged the Old World Order. And in Asia, Japan saw its chance. In 1931, it staged the Mutton incident, an explosion near a railway in Manuria and used it as a pretext to occupy the entire region.

The League of Nations condemned the invasion, but Japan ignored the protests and withdrew from the League altogether. The message was clear. Japan would go its own way. By 1937, war erupted again in China. Japanese forces invaded from Manuria and attacked Shanghai and Nangqing. What followed was brutal.

The infamous Nanking massacre where tens of thousands of civilians were killed. To Japanese commanders, this was total war. The complete subjugation of China. But instead of victory, the war dragged on. China was vast and its resistance fierce. The conflict drained Japan’s resources and isolated it diplomatically.

As Japan became increasingly dependent on imports, the Western powers grew alarmed. The United States, Britain, and the Netherlands imposed economic sanctions, cutting off vital supplies of oil and steel. To Japanese leaders, this was nothing short of strangulation. They faced a choice. Withdraw from China and lose face, or seize the resources they needed by force.

Thus, Japan’s path to the Pacific War was set not by madness, but by a grim logic of survival and ambition. In their view, war with the West was inevitable. They believed that if Japan could strike fast and hard, conquering Southeast Asia and the Pacific, it could secure a self-sufficient empire before the Americans could respond.

The plan was daring, almost suicidal. But in 1941, Japan was ready to risk everything. On December 7th, Japanese aircraft roared over Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, unleashing a surprise attack on the USPacific Fleet. Within hours, battleships were burning, and the world was at war. For Japan, it was a moment of triumph.

The rising sun had struck the mighty West with lightning speed. Simultaneously, Japanese forces swept through Southeast Asia. They invaded the Philippines, captured Hong Kong, Malaya, and Singapore, the so-called Gibralar of the East. In just a few months, the British Empire lost its most prized possessions. The Dutch East Indies with its rich oil fields fell next.

Everywhere the Japanese advanced, they presented themselves as liberators, freeing Asia from Western colonialism. Posters, speeches, and propaganda films proclaimed the birth of a new Asia for Asians. At first, many in Asia believed them. Anti-colonial movements in Burma, Indonesia, and India saw Japan as a possible ally. But the illusion did not last long. The Japanese occupation was harsh and exploitative.

In reality, the co-rossperity sphere was little more than a new empire under Japanese control. Forced labor, famine, and brutal military rule destroyed any goodwill. The dream of liberation turned into a nightmare. Yet, for a time, Japan seemed unstoppable. Its navy dominated the Pacific. Its armies held an empire stretching from the Indian border to the Solomon Islands. Never before had an Asian nation achieved such vast power.

But beneath the surface, cracks were already forming. Japan’s industrial base was too small to sustain a global war. Its resources, though expanded, were scattered and vulnerable. The empire had grown too large too fast. Supply lines stretched thousands of kilometers over ocean routes, constantly threatened by American submarines.

Worse, Japan had underestimated the resolve and industrial capacity of the United States. After the shock of Pearl Harbor, America mobilized like never before. Its factories produced ships, planes, and tanks on a scale the world had never seen. In 1942, the balance began to shift. The Battle of Midway became the turning point.

In a single day, Japan lost four of its best aircraft carriers, the core of its navy. From then on, Japan was on the defensive. Still, its soldiers fought with extraordinary courage, often to the death. The Japanese code of Bushido, the way of the warrior, taught that surrender was shameful.

This spirit gave rise to the infamous kamicazi pilots who would later sacrifice their lives in suicide missions. To the Japanese, this was not despair. It was duty. But to the rest of the world, it was a sign of fanaticism and hopelessness. As the war dragged on, Japan’s situation grew desperate. American bombing raids devastated its cities. The once proud empire was shrinking by the month.

Yet, the Japanese government refused to surrender. They hoped for one decisive battle that could force the Allies to negotiate peace. But that battle never came. By mid 1945, Japan stood alone. Germany had already fallen. The allies demanded unconditional surrender, but Tokyo hesitated.

Then in August, two atomic bombs fell, one on Hiroshima, one on Nagasaki. In a single moment, entire cities vanished. The age of the atomic bomb had begun and Japan’s fate was sealed. On August 15th, Emperor Hirohito addressed his nation for the first time in history. His voice, calm yet broken, told the Japanese people that they must endure the unendurable. Japan had lost.

The dream of the greater East Asia co-rossperity sphere was over. When the war ended, Japan lay in ruins. Cities were ashes. Millions were homeless. And the once mighty military was dismantled. Yet from this devastation, a new Japan would rise.

One that turned away from conquest and embraced peace, technology, and democracy. The same discipline that had once built an empire would now rebuild a nation. In the eyes of history, Japan’s war was both a tragedy and a lesson. A story of ambition without limit, courage without compromise, and a vision that blinded itself to reality.

From the heights of power to the depths of defeat, Japan’s journey through World War II remains one of the most dramatic and complex chapters in human history. Japan’s empire, which at first seemed invincible, began to crumble under the weight of its own ambitions. In the early days of the war, victory had seemed effortless. Each new conquest feeding the illusion of destiny.

But by late 1942, the Japanese leadership was beginning to realize that it had awakened a giant far more powerful than it had ever imagined. The United States was not only vast, but united. And once its people were fully mobilized, its industrial might became a weapon in itself.

While Japan could build perhaps a few dozen planes a month, American factories produced them by the hundreds, then by the thousands. Entire shipyards were devoted to constructing aircraft carriers faster than Japan could sink them. The Japanese Navy had once prided itself on its skill and precision, but skill alone could not match the sheer flood of American production.

Every pilot Japan lost was irreplaceable. Every ship sunk was a blow that could never be fully repaired. Back home, the situation was even more dire. The Japanese economy, already stretched thin by years of war in China, was collapsing under the strain of total war. Food shortages became common. Raw materials were rationed and fuel was scarce.

Civilians were told to grow vegetables in their backyards to support the nation. Yet, propaganda insisted on victory, even as the truth became impossible to hide. The empire that once promised prosperity to all of Asia could no longer feed its own people.

The Japanese high command was divided between the army and the navy, each pursuing its own vision of strategy. The army wanted to focus on China and defend the mainland at all costs. The navy wanted to expand southward, seizing islands and striking at the allies. This lack of unity proved disastrous. Resources were split, priorities confused, and logistics chaotic. The once coordinated machine of conquest became bogged down in endless arguments and overlapping plans.

At sea, Japan still had some of the best sailors in the world, but they faced an enemy learning fast. The Battle of Midway, fought in June 1942, was a stunning reversal. American cryptographers had broken Japan’s naval codes and knew exactly where the attack would come. In a matter of hours, four Japanese carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, were destroyed.

The loss of their elite air crews was even worse. Japan never truly recovered. From that moment on, its naval power declined relentlessly. In the jungles of the Pacific, Japan’s soldiers fought with unmatched determination. They were trained to see death as honor and surrender as shame.

This belief made them formidable opponents, disciplined, resourceful, and fearless. On islands like Guadal Canal, the fighting was brutal and relentless. Japanese troops often refused to retreat, charging into machine gun fire rather than yield ground. The cost in lives was staggering. But this very spirit of sacrifice, while admirable in its devotion, became Japan’s undoing.

The refusal to retreat meant that entire divisions were annihilated instead of regrouping to fight another day. Every battle became a fight to the death, and the death toll climbed higher and higher. America, by contrast, valued flexibility. It could afford to withdraw, reorganize, and return stronger. Japan could not.

As the war moved closer to Japan’s shores, the empire’s leaders turned increasingly desperate. They began to rely on symbolic victories, the defense of remote islands like Euoima or Okinawa, hoping that inflicting heavy casualties on the Americans would break their will to fight. Yet this hope ignored the fundamental truth of total war.

Numbers and industry decide everything. Japan’s courage could not overcome America’s endless resources. By 1944, the Allies had perfected a strategy of island hopping, bypassing heavily fortified Japanese positions and cutting them off from supply lines.

Each bypassed garrison became a prison of starving soldiers, abandoned by Tokyo, but still refusing to surrender. These pockets of resistance symbolized the tragic loyalty that defined Japan’s wartime spirit. Disciplined, proud, and doomed. Meanwhile, the American advance grew unstoppable. The US Navy, now far larger than Japan’s entire fleet, controlled the Pacific.

Long-range B-29 bombers, began striking the Japanese home islands. Cities that had once glowed with light, and life were reduced to ash. Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya all suffered devastating firebombing raids that killed hundreds of thousands. The wooden houses of Japanese cities turned into infernos and the air was filled with the smell of burning.

Still, the government refused to surrender. The emperor’s voice was silent, and the military leaders clung to the belief that one decisive battle could change everything. They dreamed of a final defense so bloody that the Americans would hesitate to invade the home islands. This was the logic behind the kamicazi.

Young men who volunteered to die by crashing their planes into enemy ships. To them, it was the ultimate act of devotion to the emperor and the nation. The first kamicazi. Attacks came during the battle of Lady Gulf in late Ki 1944. American sailors watched in disbelief as Japanese pilots deliberately dove into their ships, turning themselves into human bombs. The tactic caused terrible losses, sinking dozens of vessels and killing thousands.

Yet strategically, it changed nothing. The US simply built more ships, more planes, more everything. The sacrifice of Japan’s youth, though heroic, could not stop the inevitable. By early 1945, Japan’s situation was hopeless. Its navy was shattered, its air force crippled, and its army isolated on distant islands. The once glorious empire was reduced to defending its own homeland.

When American forces landed on Okinawa in April, they encountered ferocious resistance. The battle lasted nearly 3 months and cost more than 200,000 lives, military and civilian alike. It was the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War and a grim preview of what an invasion of Japan itself might have looked like.

The Allies now prepared for that invasion, cenamed Operation Downfall. Military planners predicted millions of casualties on both sides. But before the operation could begin, a new weapon appeared. One unlike anything the world had ever seen. In July 1945, at a place called Alamagordo, the United States successfully tested the atomic bomb.

The decision was made to end the war quickly and forced Japan’s surrender without an invasion. On August 6th, 1945, the first bomb fell on Hiroshima. In a blinding flash, the city vanished. Tens of thousands were killed instantly. Many more died in the fires that followed. 3 days later, Nagasaki suffered the same fate.

In the midst of the horror, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manuria, crushing the last remnants of Japan’s army in China. There was no hope left. Emperor Hirohito, once seen as divine, now faced an impossible choice. On August 15th, he spoke to his people over the radio. The first time any Japanese citizen had heard his voice.

In carefully chosen words, he told them that the war had not gone as planned and that they must accept the unbearable surrender. Many wept. Some refused to believe it. Others took their own lives, unable to face defeat. When the Allies arrived to occupy Japan, they found a nation in ruins.

Cities lay flattened, railways destroyed, and millions were starving. Yet the people, disciplined and resilient, began to rebuild almost immediately. Under the supervision of General Douglas MacArthur, Japan adopted a new constitution, renounced war, and embraced democracy. The emperor remained, but only as a symbol. The old military order was dismantled forever.

In the years that followed, Japan transformed itself once again, this time not through conquest, but through innovation. The same spirit of discipline and perfection that had once powered its armies now fueled its industries. In just two decades, Japan rose from ashes to become one of the world’s leading economies.

Cars, electronics, and technology replaced tanks and battleships. The rising sun shone again, not on an empire of war, but on a nation of peace and progress. Looking back, the reasons for Japan’s defeat are clear. The empire’s ambitions had outgrown its capabilities.

It lacked the resources, manpower, and industrial strength to wage a prolonged global conflict. Its leaders underestimated their enemies and overestimated their own endurance. Most of all, Japan was trapped by its own ideology. The belief that honor and willpower could overcome material reality. But in modern war, courage alone is not enough. Yet, Japan’s story remains extraordinary. Few nations have fallen so far so fast, and yet risen again with such dignity.

Its defeat was total, but not its destruction. From the ashes of Hiroshima grew a new Japan, one that turned its tragedy into strength and its shame into wisdom. The lessons of that war echo even today. Ambition without humanity leads only to ruin. And the greatest victory is not domination, but peace.

For the Japanese people, the war had always been more than a military campaign. It was a spiritual mission. To understand why Japan fought as it did, one must look beyond strategy and into the heart of its culture. For centuries, the code of the samurai, bushido, the way of the warrior, had shaped the nation’s soul.

Honor, loyalty, self-sacrifice. These were not just words, but principles of existence. A true warrior would rather die than live with shame. This ancient code forged in the feudal age of swords and lords found new life in the 20th century. As Japan modernized, its leaders revived Bushidto as a tool of unity and control. Soldiers were taught that to die for the emperor was the highest form of virtue.

From childhood, citizens learned that Japan was not merely a country but a divine family with the emperor as the father of all. To question authority was to betray that family. This belief gave the Japanese army incredible cohesion and discipline, but it also made flexibility impossible.

In a world ruled by machines, fuel, and logistics, Japan entered the war with a medieval sense of honor. Soldiers were willing to die, but not to adapt. Commanders preferred annihilation to retreat. The Bushidto code that once built heroes now trapped an entire generation in a prison of duty and pride.

In the early years of the conflict, this spirit seemed unstoppable. Japanese pilots would fly until their fuel was gone. Japanese soldiers would fight to the last bullet and entire units would commit mass suicide rather than surrender. The world was stunned by such devotion. Western observers could not comprehend it. To them, it was madness.

But to the Japanese, it was purity, a proof that their cause was sacred and their courage unmatched. Yet, as the war dragged on, that same spirit turned into tragedy. The code of honor demanded sacrifice even when the cause was lost. On isolated islands, cut off from supplies, starving Japanese troops continued to fight months after their commanders had abandoned them.

Some even resorted to cannibalism to survive, refusing to lay down their arms. For them, surrender was worse than death. At home, the Japanese government fed this ideology through relentless propaganda. Newspapers, radio broadcasts, and school lessons painted a world divided between Japan, the righteous pure nation, and the Western powers, greedy, corrupt, and cruel.

Civilians were told that Americans were demons who would slaughter every man, woman, and child. Thus, when the US bombers came, people truly believed they were fighting for the survival of their entire civilization. But propaganda could not hide reality forever.

By 1944, air raids had turned the once bustling cities into ruins. Families slept in underground shelters, rationed food, and prayed that their sons would return from the front. Yet, even in despair, there was a strange calm, a quiet acceptance that to suffer for Japan was noble. This endurance known as Garmin became a defining trait of the Japanese spirit. Meanwhile, within the highest circles of power, a silent conflict raged.

Some leaders like foreign minister Shiganori Togo knew the war was lost and urged negotiation. Others, especially the military elite, demanded continued resistance. They believed that surrender would dishonor the nation and betray the souls of the dead. For months, arguments behind closed doors decided the fate of millions.

The emperor, distant yet divine, remained a figure of mystery. Few dared to speak openly in his presence. Yet even Hirohito began to sense the futility of the struggle. Reports from the front were catastrophic. The army in Manuria shattered, the navy gone, cities destroyed, and people starving.

Still, his generals insisted they could repel an invasion. They were preparing to turn Japan itself into a fortress, a nationwide suicide defense. This plan, known as Operation Ketugo, called for every citizen to take up arms. Men, women, even children were trained to resist the coming American invasion with bamboo spears and homemade explosives. The military promised to inflict millions of casualties, believing that such a sacrifice would force the allies to negotiate peace instead of demanding unconditional surrender.

It was a desperate delusion. When the atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they did more than destroy cities. They shattered the myth of invincibility. For the first time, even the most loyal soldiers realized that death could come without warning, without battle, without honor.

The weapon that obliterated entire populations made the very concept of Bushidto meaningless. There was no glory in being vaporized. And yet, even after Hiroshima, some generals still refused to surrender. They argued that Japan must fight on, that one or two bombs could not destroy the spirit of a thousand years. It took the emperor’s personal intervention, his recorded message of surrender to end the madness.

When the broadcast played, many could not believe their ears. The divine voice they had worshiped was now telling them to lay down their arms. In some garrisons, officers wept. Others committed sepuku, ritual suicide, unable to accept the humiliation.

Across Asia, Japanese soldiers who had once seen themselves as liberators now faced the wrath of those they had oppressed. Prisoners were taken, and the great empire of the rising sun ceased to exist. For ordinary Japanese, the end of the war was both relief and heartbreak. The empire had promised glory. Instead, it brought ruin. The soldiers who returned home were ghosts of their former selves, thin, silent, haunted.

Many could not speak of what they had seen. Women searched for husbands who would never return. Children wandered through the rubble, clutching photographs of fathers lost at sea. The nation itself was in mourning. But from that morning emerged something remarkable.

Under American occupation, Japan underwent a transformation unlike any in history. The old military order was dismantled. The samurai spirit, once harnessed for war, was redirected toward peace and creation. Hey, instead of conquering through battle, Japan would now conquer through excellence. In craftsmanship, discipline, and innovation. Factories that once built warplanes began producing radios and cars.

Engineers who had designed weapons turned their skills toward electronics and machinery. Schools shifted from militaristic indoctrination to democratic education. The emperor, once a god, became a symbol of national unity in a new peaceful constitution. For many Japanese, this rebirth was painful.

It meant confronting the crimes of the past, the massacres in China, the brutal treatment of prisoners, the suffering inflicted on millions across Asia. For years, Japan struggled with how to remember its war. Some sought to honor the dead as heroes. Others insisted on acknowledging the victims. The debate continues even today. Yet, despite the shadows of history, postwar Japan achieved something extraordinary.

In less than two decades, it rose from total defeat to economic superpower. Its cities were rebuilt with modern efficiency. Its industries became world leaders. The same discipline that once fueled the military now powered technological innovation. Companies like Sony, Toyota, and Panasonic became global symbols of quality and precision. This transformation was not merely economic. It was spiritual.

Japan had learned that strength need not come from conquest. True power could be found in perseverance, creativity, and cooperation. The humility born from defeat became the foundation of a new national identity, one that valued harmony over domination, peace over pride. In a way, Japan’s loss in the Second World War saved it from self-destruction.

Had the empire survived, it might have collapsed under its own weight or fallen into civil war. Instead, its defeat forced the nation to reinvent itself. The same people who once shouted banzai. For the emperor now built a democracy that prized balance and progress. For the world, Japan’s story stands as both a warning and a hope.

Her warning of how ideology and pride can blind a nation to reality, but also a hope that even the deepest wounds can heal. The land that once brought destruction to Asia became one of its greatest builders. The people who once fought in darkness now lead in light. From the burning skies of Hiroshima to the neon lights of Tokyo.

Japan’s journey through the 20th century is one of the most profound transformations in human history. It shows that defeat is not the end. It is a beginning. The empire of the rising sun fell. But from its ashes rose a nation that finally understood the true meaning of victory. When the guns fell silent and the echoes of war faded, Japan stood at the edge of an abyss. Cities were nothing but smoking ruins, factories reduced to rubble, railways twisted and broken.

Millions were dead. Millions more homeless. The once proud empire that had dreamed of ruling Asia now faced starvation and despair. The rising sun had set, and for the first time in history, Japan was under foreign occupation.

American troops led by General Douglas MacArthur arrived not as conquerors but as architects of a new Japan. They found a nation traumatized yet disciplined. A people ready to obey, rebuild, and begin again. MacArthur himself later said that Japan’s surrender had been the most magnanimous in history. Not because it was generous, but because it was complete. The old Japan was gone, and what would rise in its place would be something entirely new.

The occupation, which lasted from 1945 to 1952, reshaped every part of Japanese life. The military was dissolved, weapons were banned, and the empire was stripped of its colonies. The emperor, once considered a living god, was forced to renounce his divinity in a public declaration. For the first time, Hirohito became human in the eyes of his people.

A man who had seen his nation destroyed and vowed that it would never happen again. In 1946, a new constitution was written, one that forever changed Japan’s destiny. It established democracy, civil rights, and the equality of men and women. Most remarkable of all was Article 9, the clause in which Japan renounced war as a means of settling international disputes.

For a nation once built on the sword, this was revolutionary. The Japanese army became a self-defense force, existing only to protect the homeland. The soul of Bushida was reborn, not for conquest, but for peace. Yet the transformation was not without pain. In Tokyo, war crimes trials were held for those responsible for Japan’s aggression.

Generals, ministers, and industrialists were brought before the tribunal to face justice. Some were hanged, others imprisoned. For many Japanese, these trials were confusing. The line between duty and guilt had blurred. Soldiers who had once believed they were defending their country were now told they were criminals. It was a moment of national reckoning.

A painful but necessary confrontation with truth. As the years passed, Japan began to rebuild. With American aid and guidance, factories rose where bombed out ruins once stood. Roads, bridges, and ports were restored. Schools reopened, teaching not war, but peace and science. Children who had grown up under the shadow of destruction now studied to become engineers, doctors, and artists.

Slowly, the wounds of the nation began to heal. In the 1950s, the miracle began. Japan’s economy, once dead, surged to life. The same efficiency and precision that had driven its wartime industry were now channeled into peaceful production. Companies like Toyota, Nissan, and Honda transformed the automobile world.

Sony, Panasonic, and Toshiba brought innovation to homes across the globe. Japanese craftsmanship became synonymous with quality, reliability, and elegance. The world watched in awe as a nation once synonymous with war became a symbol of progress. But beyond steel and technology, something deeper changed. The Japanese people redefined what it meant to be strong.

They learned that true strength lies not in domination, but in endurance, not in the sword, but in the spirit. The culture of perseverance known as Gambaru became a national philosophy to keep going no matter the odds. At the same time, Japan faced its past in complex ways. Memorials were built, textbooks rewritten, survivors interviewed, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial became a universal symbol of humanity’s capacity for both destruction and hope.

Each year on August the 6th, the nation falls silent for one minute. Not to glorify war, but to remember what must never happen again. Art, literature, and film reflected this inner transformation. Directors like Akira Kurasawa and writers like Yukio Mishima and Kenzaburoi captured the tension between tradition and modernity, between pride and guilt, between memory and rebirth.

The Japan that emerged was no longer the Japan of the sword, but the Japan of reflection, a nation aware of the cost of its past and determined to shape a better future. By the 1970s, Japan had become an economic superpower. Its cities once flattened now glowed with neon lights.

Bullet trains sped across the countryside, and Tokyo stood as one of the great capitals of the modern world. But despite its success, Japan remained humble, cautious of nationalism, wary of repeating history. The shadow of the war still lingered, not as a wound, but as a reminder. And in that reminder lay wisdom. The story of Japan in World War II is not merely one of defeat, but of transformation.

The same nation that once sought to rule by fear became a force for peace. The same discipline that once fueled war now drives art, technology, and culture. The same people who once marched under the rising sun now worked toward a world where no sun ever sets on peace. In the end, Japan lost the war not because it lacked courage, but because it fought the wrong kind of battle.

It believed that honor could overcome industry, that willpower could replace resources, and that sacrifice could substitute for strategy. But the modern world runs on logic, not legend. When the bombs fell and the myths burned away, what remained was something far greater, the resilience of a people who refused to die.

Today, Japan stands as proof that even the darkest defeat can become the seed of renewal. Its cities hum with life. Its culture inspires millions, and its people have turned their pain into progress. The rising sun still shines not on an empire, but on a nation that found its greatest victory in peace. The lesson of Japan’s journey is eternal.

Power fades, empires fall, but humanity endures. And sometimes the only way to find light is to first pass through the fire.

News

A STREET GIRL begs: “Bury MY SISTER”, the UNDERCOVER MILLIONAIRE WIDOWER’S RESPONSE will shock you

A STREET GIRL begs: “Bury MY SISTER”, the UNDERCOVER MILLIONAIRE WIDOWER’S RESPONSE will shock you Sir, can you…

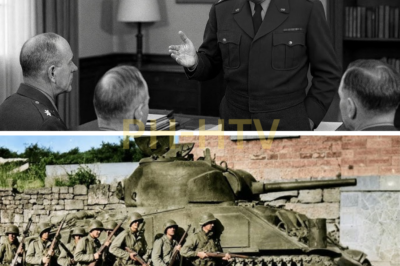

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Really Said When Patton Reached Bastogne Ahead of Everyone

What Eisenhower Really Said When Patton Reached Bastogne Ahead of Everyone December 1944 arrived over Western Europe with a cold…

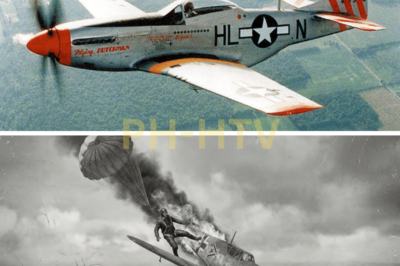

ch2-ha-German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds

German Pilots Laughed at the P-51D, Until Its Six .50 Cals Fired 1,200 Rounds in 15 Seconds March 15, 1944,…

ch2-ha-What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours In the closing winter of 1944,…

ch2-ha-The Greatest Worst Spy Ever

The Greatest Worst Spy Ever There really is nothing quite like the element of surprise. When the Allied forces appeared over…

ch2-ha-When Winter Becomes a Death Trap: Manstein’s Horrific Counterattack at Kharkov – WW2 Documentary

When Winter Becomes a Death Trap: Manstein’s Horrific Counterattack at Kharkov – WW2 Documentary The year was 1943. The…

End of content

No more pages to load