19-Year-Old P-47 Pilot Pulled Wrong Lever And Accidentally Created a Dive Escape Still Taught Today

Somewhere over occupied France, a teenage pilot yanks the wrong lever in a screaming dive. His thunderbolt flips inverted. Enemy fighters peel away in confusion. He survives. Two weeks later, fighter command orders every squadron to learn what he did. A mistake becomes doctrine. Spring of 1944. The air war over Europe has become a mathematics of attrition.

Every day, hundreds of American fighters escort bombers deep into the Reich. Every day, Luftvafa interceptors rise to meet them. The kills are counted, the losses are tallied, and the numbers tell a grim story. FW190s and BF 10009s own the vertical fight. German pilots have learned to exploit a deadly advantage. They climb higher.

They dive faster. And when an American pilot tries to follow a German fighter down through a cloud deck or into a twisting valley, the German often escapes while the American either breaks off or dies trying to keep up. The problem is not courage. It is physics. The Republic P47 Thunderbolt is a monster of an aircraft.

7 tons fully loaded, 850 caliber machine guns, a turbo supercharged radial engine that churns out 2,000 horsepower. It can absorb punishment that would shred a Mustang or a Spitfire. Pilots call it the jug. It is a flying tank. But in a dive, it becomes something else. It becomes uncontrollable. Past 450 mph, the controls lock up.

The stick feels like it is set in concrete. The rudder pedals refuse to move. The ailerons freeze. The nose drops and the pilot has no way to pull out. Some men have broken bones trying to haul back on the stick. Others have bailed out rather than ride the dive into the ground. And so the doctrine is simple.

Do not pursue in a steep dive. Do not exceed 400 mph. If a German dives away, let him go. Live to fight another sorty. It is a doctrine born of necessity, and it is a doctrine that costs lives because every enemy who escapes is an enemy who will return tomorrow. The eighth air force loses fighters. It loses pilots.

And it loses the psychological edge that comes from knowing you can chase your enemy anywhere and win. Engineers have tried to solve it. Republic Aviation has tested trim systems, control linkages, hydraulic boosters. Nothing works. The problem is compressibility. At high speed, the air flow over the elevators changes. The tail loses authority.

The plane wants to tuck further into the dive. And the only solution is to throttle back. Deploy dive brakes if you have them and pray you have enough altitude to trade for time. But the P47 has no dive brakes. It has only speed, weight, and a pilot fighting for control. By the spring of 44, this is accepted reality.

This is the edge of what the Thunderbolt can do, and every pilot knows it. If this history matters to you, tap like and subscribe. Second Lieutenant Robert L. Booth is 19 years old. He has 67 hours in the P47. He has flown five combat missions. He is assigned to the 56th Fighter Group stationed at Boxstead in Eastern England.

The 56th is one of the oldest Thunderbolt outfits in the theater. Its pilots have painted wolf heads on their fuselages. They call themselves the Wolfpack. Booth is not a natural pilot. He is not one of those cadetses who soloed in eight hours and flew aerobatics on his second day. His instructors in the states described him as methodical, careful, a little slow to react, but solid on procedures.

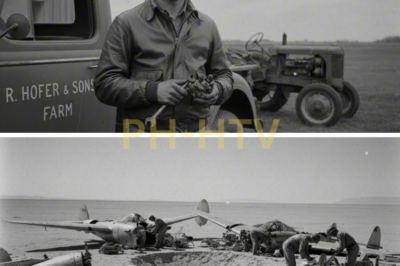

He does not drink much. He does not boast. He writes letters to his mother in Pennsylvania twice a week. He grew up on a farm outside Allentown. He knows engines because he spent his teenage years fixing tractors and combines. He knows patience because farming teaches you to solve problems in sequence, not panic.

He joined the Army Air Forces in 1942 because he wanted to serve and because he had no interest in the infantry. Flight training was harder than he expected. He washed out of pursuit training once and had to restart. He graduated near the middle of his class. He arrived in England in March of 44. He was assigned to the 63rd Fighter Squadron.

He flew his first mission on April 2nd. He did not fire his guns. His squadron mates are older. Most of them have 10 or 15 missions. A few have 20. They tolerate him. They do not trust him yet. Trust is earned in combat, and Booth has not done anything to earn it. He has stayed in formation. He has followed orders.

He has not panicked, but he has not proven himself either. On the morning of April 18th, the squadron is tasked with a bomber escort mission to Brandenburgg. The weather is poor. Cloud layers stack from 8,000 ft up to 20,000. Visibility is less than 2 mi. The bombers are late. The group orbits over the channel, burning fuel, waiting for the heavies to form up.

Booth flies tail end Charlie, the last plane in the formation, the spot reserved for the new guys. He checks his instruments every 30 seconds. Oil pressure, fuel, manifold pressure, coolant temperature. Everything is normal. His hands are cold inside hisgloves. The cockpit smells like oil and rubber and sweat. They cross the coast at 10,000 ft.

The flack starts immediately. Black puffs stitching the sky. The formation tightens. Booth tightens with it. He keeps his eyes on the plane ahead. He does not look at the flack. If you look at it, you start to flinch. If you flinch, you drift out of position. Somewhere ahead, the bombers are hitting their target.

Booth cannot see them. He can only see clouds and the gray green flicker of the wing ahead of him. And then the radio crackles. Bandits high and to the north. The FW190s come out of the sun. Four of them, maybe five. They make one slashing pass through the formation and then split. Two go left, two go right. One dives straight down through the cloud deck.

The squadron breaks. Booth follows his element leader into a hard right turn. The G force shoves him down into his seat. His vision tunnels. He tightens his stomach muscles and grunts against the pressure. The world is sky and clouds and the white painted belly of the plane ahead. His element leader rolls left and dives. Booth follows.

They drop through a gap in the clouds. Below them, the lone FW190 is running east at full throttle, 50 ft off the ground, following a river valley. The element leader closes fast. Booth closes faster. The thunderbolt is heavy, and in a dive, it builds speed like a locomotive. Booth watches his airspeed indicator climb.

300 mph, 320, 350. Ahead, the element leader opens fire. Tracers arc toward the German. The FW190 snaps into a hard left brake and disappears behind a line of trees. The element leader pulls up and climbs back toward the cloud deck. Booth does not follow. He is fixated on the spot where the German disappeared. He banks left. He drops lower.

He is at 200 ft now. The river is a gray ribbon below. He can see individual trees. He can see a church steeple. He can see the Fu90 climbing vertically out of the valley, looping back toward him. Booth fires. He does not lead the target properly. His rounds fall behind. The German rolls inverted at the top of the loop and dives again. Booth tries to follow.

He pushes the stick forward. The nose drops. The air speed jumps. 400 mph. 420 450. The controls lock up. He pulls back on the stick. It does not move. He pulls harder. Nothing. The nose is dropping steeper. The river is rushing up. He is in a 70° dive. The altimeter is unwinding. 1,500 ft. 1 1200 1,000. He plants both boots on the instrument panel and hauls back with everything he has. The stick moves an inch.

The nose comes up a fraction. Not enough. He is going to hit. And then in a moment of pure panic, he reaches for the landing gear lever and pulls it. He means to pull the flap lever. He has some half-formed idea that flaps will slow him down. But his hand is shaking and the cockpit is vibrating and he grabs the wrong control.

The landing gear drops into the slipstream. The deceleration is instant and catastrophic. The air speed bleeds off like someone cut the throttle and threw out an anchor at the same time. The nose pitches up violently. The plane shutters. Booth is thrown forward against his harness. His head hits the gunsite. The horizon spins.

He is inverted. He is climbing. He has no idea what just happened. He rolls upright by instinct. He is at 3,000 ft. The air speed is 210. The controls are responsive again. He looks around. No German, no river, just clouds and empty sky. His gear warning light is on. He retracts the gear. The plane smooths out.

His hands are shaking so hard he can barely hold the stick. He does not understand what he just did. But he is alive. He climbs back through the clouds and rejoins the formation 15 minutes later. Nobody asks where he went. That night, Booth sits on his bunk and tries to reconstruct the sequence. He dropped the gear. The plane decelerated.

The nose pitched up. He recovered. Cause and effect. But it does not make sense. Lowering the gear is not a recovery technique. It is not in any manual. It is not part of any training. It is a mistake, but it worked. He tells his roommate. The roommate shrugs and tells him he got lucky. Booth does not argue, but he cannot stop thinking about it.

The next day, he mentions it to his flight leader during debriefing. The flight leader is a captain from Texas with 12 kills and a distinguished flying cross. He listens. He nods. He tells Booth that panic makes you do strange things and that he should forget about it and focus on staying in formation. Booth tries to let it go, but the physics nag at him.

The gear created drag. The drag bled off speed. The speed reduction restored control authority. It is logical. It is repeatable. It is a solution. Two days later, he brings it up again. this time to the squadron engineering officer. The engineering officer is a first lieutenant who flew 10 missions before he was transferred to a desk job.

He knows the P47 inside and out. He has read every technical order.He has heard every pilot complaint. He tells Booth it is an interesting idea. He also tells him it is dangerous. Dropping the gear at 450 mph could rip the gear doors off. It could tear the wheels out of the wells. It could overstress the airframe. And if the gear does not retract afterward, the pilot is stuck with a slow, draggy airplane in the middle of a combat zone.

Booth listens. He nods. He understands the risk, but he keeps thinking about the river and the locked controls and the fact that he should be dead. The engineering officer makes a note. He says he will pass it up the chain. Booth does not expect anything to come of it. But 3 days later, the group commander calls him into his office.

Colonel Hubert Zama is 30 years old. He has been flying fighters since before the war. He commands the 56th Fighter Group. He has 22 kills. He does not tolerate fools and he does not tolerate carelessness. But he listens to ideas, especially ideas that come from pilots who have nearly died.

He tells Booth to explain exactly what happened. Booth does. He describes the dive, the locked controls, the wrong lever, the pitchup, the recovery. He speaks slowly and precisely. He does not embellish. Zena asks how fast he was going when he dropped the gear. Booth says 450, maybe 460. Zama asks how much altitude he lost before recovering.

Booth says 500 ft, maybe less. Zena asks if the gear retracted normally afterward. Booth says yes. Zena leans back in his chair. He is quiet for a long moment. Then he tells Booth he wants to test it. controlled conditions, high altitude, chase plane with a camera. If it works, they will teach it.

If it does not, they will bury the idea and forget it. Booth agrees. The test is scheduled for April 25th. Booth takes off at 0900 hours. The sky is clear. Visibility is unlimited. A P47 from the intelligence section flies Chase 500 ft above and behind with a K24 camera mounted in the wing. Booth climbs to 20,000 ft. He checks his instruments.

Everything is normal. He takes a breath. He pushes the stick forward. The dive is controlled at first. 30° 40 50. The air speed climbs 300 350 400. The controls begin to stiffen. He pushes further. 60° 65 420 440 450. The stick locks. The rudder pedals freeze. The nose wants to drop further. He lets it. 70° now.

The altimeter spins. 18,000 17. The engine roars, the wings vibrate, the whole airframe shakes like it is going to come apart. He reaches for the gear lever. He hesitates for just a fraction of a second. Then he pulls it. The gear doors snap open. The wheels drop into the slipstream. The drag is immediate and immense. The plane shutters.

The nose pitches up hard. The geforce slams him into the seat. His vision grays at the edges. The air speed drops like a stone. 430 400 370 340. The controls come alive. He pulls back on the stick. The nose rises. The dive shallows. 40° 30 20 level. He is at 14,000 ft. He has lost 6,000 ft in less than 10 seconds, but he has recovered.

He retracts the gear. The plane accelerates. He climbs back to 20,000 and does it again. This time he waits until 460 mph. Same result. Violent deceleration, pitch up, recovery. He does it a third time at 470. Same result. The chase plane captures all three attempts on film. Booth lands at 10:30.

His hands are shaking again, but this time it is adrenaline, not fear. ZMK reviews the film that afternoon. He watches it three times. Then he calls a meeting of all squadron commanders. He tells them that as of today, the gear extension recovery is authorized for emergency use in high-speed dives. He tells them to brief their pilots.

He tells them to practice it at altitude before they need it in combat. Within two weeks, every P-47 pilot in the 56th fighter group has tried it. Within a month, the technique has spread to the fourth fighter group and the 56th. By June, it is being taught at replacement training units in England. By August, it appears in the official pilot’s handbook as an approved emergency procedure.

A 19-year-old second lieutenant who grabbed the wrong lever has rewritten doctrine. The impact is measurable. Between May and September of 1944, loss rates in high-speed diving engagements dropped by 18% across ETH Air Force Thunderbolt units. Pilots report increased confidence in pursuing enemy aircraft through vertical maneuvers.

Several afteraction reports credit the gear extension technique with saving aircraft and lives. On June 7th, a P-47 pilot from the 56th pursues an FW190 into a nearvertical dive over Normandy. His air speed hits 480 mph. He drops the gear. He recovers at 3,000 ft. He climbs back up and shoots the German down. In his mission report, he writes that without the technique, he would have either broken off or crashed.

On July 14th, a pilot from the fourth fighter group uses it to recover from a compressibility dive after his elevator trim malfunctions. He lands safely. The plane is repaired and returned to service. On August 22nd, a pilot fromthe 56th uses it twice in the same mission. He survives both times. The technique is not without risk.

The gear mechanism is not designed for high-speed deployment. There are cases where gear doors are damaged. There are cases where one wheel extends and the other does not, causing asymmetric drag and a violent yaw. There is at least one case where the gear does not retract afterward, and the pilot has to nurse his plane back across the channel on half fuel and pray he makes it.

But in every case where it is used correctly at the right speed and the right altitude, it works. And so it becomes part of the culture. New pilots are taught it during their first week in theater. Old pilots teach it to each other. It spreads beyond the eighth air force. Ninth air force units adopt it.

RAF Thunderbolt squadrons adopt it. By the end of the war, it is standard knowledge. The Luftwaffa notices German intelligence reports from late 1944 reference American pilots recovering from dives that should have been fatal. Some German pilots begin to avoid diving away from thunderbolts knowing that the American can now follow them down and recover.

The psychological advantage shifts. It is a small thing, one technique, one control input. But in a war of inches, small things accumulate. And this small thing saves lives. Booth himself uses it twice more before the war ends. Once over Belgium in September. Once over Germany in March of 45. Both times it works. Both times he walks away.

Robert Booth survives the war. He flies 62 combat missions. He is credited with two kills and three probables. He is awarded the distinguished flying cross and the air medal with four oakleaf clusters. He is promoted to first lieutenant. He returns to Pennsylvania in July of 1945. He does not talk much about the war. He goes back to the farm.

He marries his high school sweetheart. He raises three children. He works as a mechanic for a John Deere dealership. He fixes tractors and combines the same machines he fixed before the war. He does not fly again. In 1973, he receives a letter from the Air Force Museum in Dayton. They are researching the history of P47 tactics.

They have found references to the gear extension recovery technique. They have traced it back to the 56th Fighter Group. They have found his name in the mission reports from April of 44. They ask if he would be willing to be interviewed. He agrees. He drives to Dayton. He sits in a small office with a historian and a tape recorder.

He tells the story, the dive, the locked controls, the wrong lever, the recovery. He speaks in the same slow, precise way he spoke to Colonel Zama 30 years earlier. He does not embellish. The historian asks if he knew at the time that he had discovered something important. Booth says no. He thought he had made a mistake and gotten lucky.

He did not realize it was repeatable until he tested it. The historian asks if he is proud of it. Booth is quiet for a moment. Then he says he is proud that it helped. That is all that it helped. The interview becomes part of the museum’s archives. The technique itself is studied by test pilots and aeronautical engineers in the decades that follow.

It becomes a case study in emergency flight control recovery. It is referenced in papers on compressibility and high-speed aerodynamics. It is taught in modified form to jet pilots in the 1950s and60s. The principle remains the same. Increase drag, bleed off speed, restore control authority. Booth dies in 1991.

He is 66 years old. His obituary in the Allentown paper mentions his service in the war. It does not mention the dive. It does not mention the lever. It does not mention the technique that carries his name in Air Force training manuals for the next 50 years. But the pilots know the ones who flew Thunderbolts.

the ones who trained on them, the ones who teach the history. They know that a teenager who grabbed the wrong lever in a moment of panic gave them a way to survive what should have been unservivable. And that is the legacy. Not fame, not recognition, just the quiet knowledge that when logic and panic collided at 450 mph, one young man stumbled onto an answer. And that answer saved lives.

Sometimes the difference between death and survival is a single lever. And sometimes the person who finds it does not even know what they have done until someone else tells them it matters. Booth knew. He just did not need anyone to say

News

ch2-ha-The Germans laughed at the “handful of Poles” until Skalski shot down 6 aces in 15 minutes

The Germans laughed at the “handful of Poles” until Skalski shot down 6 aces in 15 minutes April 20, 1943…

ch2-ha-Japanese Couldn’t Stop This Marine With a Two-Man Weapon — Until 16 Bunkers Fell in 30 Minutes

Japanese Couldn’t Stop This Marine With a Two-Man Weapon — Until 16 Bunkers Fell in 30 Minutes At 0900 on…

ch2-ha-The $45 Gun That OUTPRODUCED Every Weapon America Ever Made

The $45 Gun That OUTPRODUCED Every Weapon America Ever Made October 1941, a typewriter company, a jukebox maker, and a…

ch2-ha-Why Patton Had to Steal Supplies to Cross the Rhine

Why Patton Had to Steal Supplies to Cross the Rhine August 31st, 1944, General George S. Patton stood in a…

ch2-ha-They Called It Impossible — Until This Sniper Killed 87 Germans in 72 Hours Alone

They Called It Impossible — Until This Sniper Killed 87 Germans in 72 Hours Alone At December 19th, 1944, 4:47…

ch2-ha-This 18-Year-Old P-38 Cadet Slipped Into a Spin And Discovered a Trick That Outturned 5 Enemy

This 18-Year-Old P-38 Cadet Slipped Into a Spin And Discovered a Trick That Outturned 5 Enemy 18,000 ft over California,…

End of content

No more pages to load