Can you try it just once, please? I’ll pay you anything. Can you breastfeed him even just once? the cowboy begged. The plump girl hugged the baby to her breast. The Saturday market smelled of freshly baked bread and pure cruelty. Nora arranged the loaves on her wooden table, her hands quick and expert.

The customers bought without looking at her, tossed in the coins. They grabbed the bread. Not a thank you, nothing. Pure silence. It had been like this for six weeks. Since her husband died, since her baby was born blue and without a cry, since the boarding house took her in and called her charity. The other vendors didn’t even acknowledge her. The customers pretended she didn’t exist.

It was invisible until the scream began. A baby’s cry cut through the noise of the market. A desperate wail, as if it were dying. The crowd parted and a man staggered into the square. Broad shoulders, a three-day beard, eyes wild with exhaustion, his shirt stained dark, his hands trembling as he held a small bundle. “The baby is so tiny, too still. Please,” his voice broke.

Someone help me. He hasn’t eaten in three days. The women stepped back. The men turned their faces away. The baby’s cry was now barely a whisper. “And the mother?” someone finally asked. The man clenched his jaw. “She died in childbirth three weeks ago.” A murmur of surprise swept through the plaza.

I went to all the wet nurses in three counties. They all turned me away. Near the vegetable stand, two ladies were whispering loud enough to be heard. It’s Tomás Alles, the one who punched his father. He got into a fight in the canteen last week. They say he has a temper. His wife died because no one wanted to help.

The village decided it wasn’t worth it and now wants us to breastfeed their child after the way it behaved. The women turned their backs, and the others followed suit. Tomás heard everything. His fists clenched. Rage flashed across his face, but then he looked at his daughter, at her gray skin, at her almost nonexistent breath, and his fury crumbled into tears.

“Please,” she whispered. “She’s dying. I don’t know what to do anymore.” Nora stopped moving her hands over a loaf of bread. She saw the tiny baby struggling. She held her own silent daughter in her arms, a child who never breathed. Old Marta, the herbalist, stepped forward and pointed at Nora. She, the widow, had lost her baby a month ago.

She must still have milk. All heads turned. Tomás crossed the square in heavy boots, desperate, and stood in front of the table. Up close, Nora saw the exhaustion etched on his face, the rage about to explode, the pain that choked him. “Can you breastfeed her, even just once? Please, I’ll pay you whatever you ask.” Nora looked at the dying baby.

Before she could speak, laughter erupted behind her. Three women from the boarding house. The fat widow, you’re asking her. She couldn’t even keep her own son alive with that body, and she still lost him. Maybe she crushed him with all that weight. The market roared with laughter. Tomás turned around, his fist raised.

Nora grabbed his arm. “No, look at her.” His arm trembled with pure fury under Nora’s hand. “They’re not worth it,” he said softly. Slowly. His fist opened. He turned to Nora. “Will you help me?” She looked at the baby. She looked into Tomás’s desperate eyes. “I live in the boarding house, two blocks away. Bring her there.” Relief flooded her face. “You’re really going to try?”

I’ll try. Tomás let out a breath as if he hadn’t breathed in days. Thank you. Behind him, the murmurs exploded. He takes her to his room. Single, shameless, the fat widow sleeping with the first man who looks at her. Nora didn’t look back, she put away the bread she hadn’t sold and started walking. Tomás followed close behind her.

He stopped on the boarding house stairs. I don’t even know your name. Nora. Tomás. Thank you for not turning your back on me. Inside. The boarding house girls were spying from the kitchen doorway. Nora led him up the narrow staircase to her small attic room. The whispers followed him. Give him an hour. He’ll come down on his own. The baby’s dying anyway. Nora closed the door.

The room was small: a bed, a wooden chair, a broken mirror. Tomás stood in the middle with his daughter, lost in thought. “Sit down,” Nora said softly. She took the chair. Tomás knelt beside her. Carefully, Nora received the baby. She weighed next to nothing. Her eyes were closed, her breath barely a whisper.

Nora unbuttoned her dress and brought the baby to her breast. At first, nothing. Her milk had almost dried up. The baby’s little mouth moved weakly, trying, failing. “Come on, my queen,” Nora whispered. “Please, try.” And suddenly, the baby latched on and nursed. Tomás let out a sound somewhere between a whimper and a gasp. “He’s nursing, my God, he’s nursing!” Tears streamed down her face, and she didn’t wipe them away.

Nora’s eyes fell silent. Three weeks making milk for a baby who would never drink it. Now a creature lived for her. Tomás slumped to the floor beside the chair, his shoulders trembling. I thought I was losing her like I lost Sara. I thought God was taking everything from me. Nora said nothing, she just rocked, she just let the baby nurse.

Outside, the sun crossed the sky. Inside, three broken people found their first moment of peace. When the baby let go of the breast, she was already pink instead of gray, breathing more deeply. Tomás looked up. “You saved her life.” Nora carefully handed the child back to him. “She’ll want it again in a few hours. Can I bring her?” Nora hesitated. The boarding house owner would be furious.

The girls would laugh endlessly, but the baby was alive. Yes. Tomás got up and held her close to his chest. He returned before sunset. He stopped at the door. “The women at the market were mistaken about you. You’re not here.” Nora lowered her gaze. “You don’t know.” “I do know because my daughter is alive. And that’s not a curse, that’s a miracle.” He left. Nora was left alone in her little room.

Outside, she could hear the girls laughing and gossiping, hoping she would fail. But for the first time in six weeks, she didn’t feel useless. Today she had saved a life, and tomorrow Tomás Alles would return, not because he had to, but because he needed her, and perhaps that was enough. Tomás returned at dusk. The girls from the boarding house were in the kitchen when he knocked loudly, urgently.

They scattered to spy as Nora opened the door. Tomás was on the porch. The baby in his arms. She looked better now. Rosy cheeks, louder crying. She’s hungry again. Nora glanced at the shadows where the girls lurked. Sharp eyes. Come in. The murmurs started immediately. Second time today. This is awful.

She was brazenly offering herself to him. Nora led him upstairs again. Each step felt heavier under their stares. In the room, she breastfed the baby while Tomás sat on the floor, his back against the wall. “I want to ask you something,” he said softly. Nora looked up. “Come to the ranch for a few weeks until I’m stronger. I’ll pay you my full salary. You have your own room with a lock.”

Nora stood still. “Tomás, I can’t just come twice a day anymore. The ranch is falling apart. I haven’t slept more than an hour at a time since Sara died.” Her voice broke as she said the name. “I need help. Not just with her, with everything.” Nora looked at the baby nursing contentedly. “The town is going to talk. It already is. It’s going to talk even worse.”

“I don’t give a damn what they say,” Tomás said. “My wife died because this town decided I wasn’t worth helping. Let them think what they want. I’m asking you. Will you come?” Nora thought of her little tin room, the taunts, the loneliness, having nowhere else to go. “I’m coming.” Tomás’s shoulders relaxed with pure relief. “Thank you.”

The next morning, Nora packed her spare dress, her mother’s hairbrush, and a Bible into a suitcase. The girls from the boarding house lined up in the hallway as she went downstairs. “She’s going to play house with the grumpy rancher. She’ll be back in a week. They always send the fat ones back.” The landlady came out of the kitchen. “So, you’re leaving?” “Yes, ma’am.”

You owe three months’ rent. 50. Nora’s heart sank. She’d forgotten about the debt. I’ll pay it as soon as I can. You pay it now, or you stay until you work it. Tomás appeared in the doorway, holding the baby. How much do you owe? The landlady’s eyes gleamed. 50. Tomás took out his wallet, counted the bills, and gave them to her. 60. That settles everything and pays her for her trouble.

The owner stared at the money, mouth agape. Tomás turned to Nora. “You’re free. Let’s go.” The cart was waiting outside. Tomás helped her in, handed her the baby, and then got in himself. As they drove away, the voices faded. “He really paid her the debt, 60 pesos for her. That guy’s desperate.” The cart rolled through the town. People watched and whispered.

Nora kept her eyes straight ahead. “They’re going to make your life a living hell,” she said quietly. Tomás clenched his jaw. “They already did. The day they let my wife die, they sat around in silence for a while.” Then Tomás spoke. “The ranch isn’t much to look at. It’s a mess. I haven’t had time. I’ll help you.” He glanced at her sideways. “I hired you to breastfeed Grace, not to clean my house.”

I know, but I need to feel useful for more than just my body. Tomás nodded slowly, understanding. The ranch appeared on the hill, larger than Nora had expected, with clean fences, a sturdy corral, and a solid house. But as she approached, she saw the truth: clothes piled on the porch, a driveway overgrown with weeds, and chickens roaming freely.

The ranch was slowly dying. Tomás saw her looking. I know it’s ugly. It’s not ugly. It’s in mourning. He stopped the cart and looked at her straight on. Your room is behind the kitchen. It belonged to the farmhand. It’s locked from the inside. Thank you. Inside it was chaos. Dishes up to the ceiling, dust everywhere, baby things scattered about.

But the house was well-built, with strong wood, large windows, and a stone fireplace. Tomás showed her his small but clean room, with a real bed and a window overlooking the pasture. “It’s perfect,” Nora said. That afternoon, after breastfeeding Grace, Nora couldn’t wait; she washed dishes, swept, and folded the clothes on the table. Tomás came in from feeding the horses and stood in the doorway. “You didn’t have to do that.”

I know. I hired you for Grace. Nora kept folding. I need to work. It’s the only thing that takes my daughter off my mind. Tomás grabbed a rag and started drying dishes beside her. They worked quietly side by side. When the kitchen was clean, Tomás made coffee and placed a cup in front of her without asking. “Thank you,” she said softly. “You really know how to take care of things.”

My mother taught me before she died. And your husband? Nora stood still with the cup. He taught me that not all men are good. Tomás fell. Sorry. It’s over now. He’s gone. They remained in comfortable silence as darkness fell. R slept in his crib between them. For the first time since Sara died, Tomás’s house didn’t feel empty.

For the first time since her baby died, Nora felt she belonged somewhere. Two weeks passed. Gr was growing rapidly, his cheeks chubby, his cries loud, grabbing everything with his tiny fists. But Nora saw the rest: the chicken coop in ruins, the hens stressed and not laying eggs, the vegetable garden ruined, the fence of the north pasture about to collapse, the roof of the corral leaking and spoiling the hay.

Tomás worked from sunrise to sunset, but he was one man doing the work of two. One morning, after breastfeeding, Nora went to the henhouse. It was a disaster. Rugged nests, rotten straw. It was no wonder they weren’t laying eggs. She found some tools in the coop and got to work. Two hours later, Tomás came looking for her and was stunned.

Nora, covered in dirt and feathers, was hammering new boards. The henhouse was swept, fresh straw was laid, and the hens were calmer now. “What are you doing?” “Fixing up your henhouse.” “I was going to do it.” “I know, but you’re doing the work of three.” She hammered another nail. “And I’m here, and I know how to work.” Tomás watched her finish.

Where did you learn carpentry? My father, before he died, before I married a man who said women shouldn’t touch tools, stood up and dusted off his dress. I’m not useless, Tomás. Just because I’m chubby doesn’t mean I’m useless. Tomás came closer. I never thought you were useless. They looked at each other. Something changed in the air. The hens will lay again tomorrow,” Nora said more quietly. “Thank you.”

She walked past him. He gently grasped her wrist. “Not to control me. You don’t owe me this job. I know that. So why?” She looked at the hand on her scarred wrist. “Because for the first time, someone needs me for more than just my body. You need me because I work, because I’m capable.” Her voice broke.

Why are you looking at me? Tomás loosened his grip, but didn’t let go. I see you. They stayed like that for a long time. Then Grom’s crying interrupted the moment. I’m going for her. Nora watched him leave, her heart pounding. The next day she attacked the orchard. She was on her knees pulling weeds when two men arrived on horseback, the farmhands Tomás had chased away. They dismounted and went with Tomás to the corral.

Nora kept working, but the voices reached her. “Do you have an assistant yet, boss?” “Yes, she’s quite tall. I bet she eats more than she can produce.” Laughter. Tomás froze. “What did you say?” The laughter stopped. “Nothing, boss. Just chatting. Talking about the woman who saved my daughter’s life.” “We didn’t want to. Get off my land.”

What? You heard me. Go away now. Come on, Tomás. It was just a joke. Tomás approached, his voice low and menacing. You insult Nora in my land, you’ll pay for it with me. Don’t come back. The men looked at each other, mounted their horses, and rode off. Nora got up slowly, her hands trembling. He had defended her again. That afternoon, Gresle spat milk on her dress.

“Well, the only one. I’ll help you wash it,” Tomás said. “I have an old dress of Sara’s that you can wear while it dries.” They washed together in the washbasin, their hands brushing against the fabric. Their fingers met. They both stood still. Neither moved away. Tomás’s thumb caressed her knuckles. Slowly.

By the way. Nora, yes, but Grace cried from her crib. The moment was broken. I’ll go get her. Yes. That night Nora couldn’t sleep and sat on the porch steps. The door opened. Tomás sat beside her, so close she could feel his warmth. You can’t sleep. I have so much on my mind.

They remained silent, gazing at the stars. “My wife died hating me,” Tomás said suddenly. Nora turned away. “Not really hating me, but she died frightened. The midwife didn’t come because I’d sworn at her father the week before. He’d said something cruel about Sara, and I’d lost my temper. Her voice left her. When Sara went into labor, no one came. She spent hours with Dolores, begging me to stop.”

I held her hand, but I couldn’t do anything. When Gres was born, Sara was already gone. She looked at her hands. Sometimes I think that in her final moments she blamed me for my anger, for making the town hate us so much that they let her die. Nora took her hand without thinking. You didn’t kill her. This town… I should have controlled my temper, and her father should have controlled his tongue.

She squeezed his hand. “You’re not the villain, Tomás.” They were silent. Then Nora spoke softly. “My husband didn’t die in an accident.” Tomás looked at her. “He was drunk. He hit the horse because it wouldn’t start. The horse kicked him in the head. Everyone said tragedy, but I knew the truth.”

He beat the horse just like he beat me. Her voice grew stronger. Our baby was born a month after he died. She was born quiet, blue. The cord wrapped around her neck. The midwife said, “That’s how it is.” But I wondered if all the beatings he gave me while I was pregnant had damaged something inside. Tomás gently lifted her face. “You didn’t kill your baby.

“Destiny did, but not you. How do you know? Because you saved mine.” The words opened something inside her. She cried. They stayed like that until the stars went out. Two broken people learning they could be whole again together. Three weeks had passed since Nora arrived at the ranch. Grace was plump and strong. The ranch had been reborn.

A vegetable garden yielding produce, hens laying eggs daily, sturdy fences, a warm and clean house. Everything looked better, but the town never stopped gossiping. One afternoon, three women arrived in a carriage. Tomás was checking the north fence. Nora was weeding in the garden when she saw them. The landlady of the boarding house, the father’s wife, and another woman she didn’t know.

“Miss Nora,” the landlady crooned, too sweetly. Nora stood up, dusting herself off. “We’ve come to speak with Mr. Aes. He’s working in the north pasture.” “What a shame,” said the priest’s wife. “We’ve come to warn him about you.” Nora’s stomach clenched. “The whole town is talking,” the woman continued.

A single woman living alone with a man. It’s a sin, it’s shameful. “I have my own room,” Nora said quietly. “That doesn’t matter. Appearances do. And this looks very bad.” The landlady circled like a shark. “We’ve come to take you back to the boarding house for everyone’s sake, before you ruin what little reputation it has left.”

I’m not coming back. You have no choice. You still owe. Tomás paid my debt. You know that. So you live here like his mistress. The father’s wife spat. What makes you one. The word hit Nora like a slap. Before she could answer, they heard a gallop. The two farmhands Tomás had fired three weeks ago, drunk and furious, stopped beside the orchard.

Just look at that. One babbles. The fat lady has a visitor. The women took a step back. Auntie Nora’s heart. They have to leave. Tomás kicked them out. Tomás isn’t here, is he? The man got out so bravely. Just you all alone. The other one got out too. We’ve come for what they owe us. The boss kicked us out because of you.

“He owes us wages. I’ll pay you if you leave,” Nora said, backing away toward the house. “We don’t want money,” the first man smiled. Yellow teeth. “We want compensation.” He jumped up and grabbed her arm tightly, reeking of whiskey. “Let go of me until we get paid.” A gunshot rang out. Everyone froze. Tomás was 20 paces away, rifle raised, eyes wild with rage. “Get your hands off me.”

The farmhand let go of Nora instantly. We weren’t talking anymore. Boss, you touched her. Tomás’s voice was deathly calm. You put your filthy hands on her. He advanced slowly, rifle pointed. I told you not to come back. I told you what was happening. Tomás, no more. Get on your horses now. If I see you again in my land, I won’t be firing a shot.

I’ll shoot them right in the heart. The men ran to their horses and rode off. Tomás lowered his rifle slowly, trembling. The women stood stiffly beside the carriage. Tomás turned, his face cold with fury. You brought them here. The owner’s eyes widened. We didn’t know. You came to take her from me, to humiliate her.

And while they were calling her names, those bastards came to hurt her. The voice rose. Get out of my land. All three of them. That’s it, gentlemen, we just wanted to. They climbed into the carriage and fled. Silence fell. Tomás dropped his rifle and in three strides reached Nora. Are you alright? Did they hurt you? I’m fine. You arrived just in time. He took her face in his hands, checking her.

I shouldn’t have left you alone. I should have. Tomás grabbed her wrists. I’m okay. He pulled her to his chest, so hard she could barely breathe. When I heard you scream, your voice broke. I thought I was losing you, like I was losing Sara. I’m here. I’m safe. They stayed like that. His heart pounded against her ear. Finally, Tomás pulled away just enough to look at her. I can’t go on like this anymore.

Nora gasped. What? Pretending you’re just an employee. Pretending I need you no more than air. He stroked her cheek. I love you, Nora. I’m in love with you, and I can’t hide it anymore. Tears streamed down her face. I love you too. Then marry me. No, someday. Today, before something else happens, before someone else tries to take you from me.

Yes, she whispered. Yes. Tomás kissed her desperately, as if he’d been holding back for weeks and the dam had finally broken. When they parted, they were both panting. “Tomorrow,” he said firmly. “Tomorrow we’ll go to the village and get married.” The wait was over. Inside. R began to cry. They went to get her together. They were family now; all that was missing was the marriage certificate. Dawn broke cold and clear.

Tomás hitched the cart before sunrise. Nora sat beside him, holding her in her arms, nervous, terrified. Tomás took her hand. So did I. They entered the town as the bells rang for Mass. The streets were full of people in their Sunday best. The cart stopped in front of the courthouse. The conversations died down. Everyone turned around. The grumpy rancher and the fat widow. Together.

The murmurs spread like wildfire. Tomás helped Nora lower the firm hand on her back. They walked to the courthouse where the circuit judge held court on Sundays. The crowd parted, staring openly. “Tomás!” Sheriff Pattersen shouted, pushing his way through. The boarding house owner was beside him. Tomás turned slowly. “Sarah. Mrs. Henderson filed a complaint.”

He says you have Miss Nora against her will. Living in sin violates the ordinance. People gathered, hungry for gossip. “Miss Nora is here of her own free will,” said Tomás, his voice calm and dangerous. “It doesn’t matter, single people living together. Marry her right now or I’ll follow through on the complaint.” Tomás looked at Nora. It was the plan anyway.

Her heart was pounding. They went up the courthouse steps. The judge was at the door. “Do you want to get married now?” “Right now,” said Tomás. “This is ridiculous,” the landlady stammered. “A forced marriage.” “Nobody’s forcing me,” Nora said firmly, looking at the people. “I choose him.” The judge took out his book. “Witnesses.” Old Marta pushed her way through. “Me.”

The blacksmith took a step. So did I. The judge opened the book. “Tomás Alles, do you take this woman to be your wife?” “I do.” “Nora, do you take this man to be your husband?” “I do, and by the power vested in me by the state, I now pronounce you husband and wife.” He slammed the book shut. “Kiss your wife.” Tomás took her face in his hands and kissed her.

There on the courthouse steps, shamelessly in front of everyone. People gasped. When they separated, Tomás turned around, his arm around Nora. “She’s my wife now. Legal. Does anyone have a problem with that?” Silence. Then the landlady spoke. “This doesn’t change who she is.” “Careful,” Tomás interrupted, his voice deadly. “You’re talking about my wife.” The landlady’s face turned green.

The town knows she caught you. She saved my daughter when all of you refused. Tomás shouted. She saved my ranch. She saved me when I wanted to die of sadness. She brought her closer. So yes, she’s in my house, in my life, in my heart, and I’m very proud of that. One of the girls from the boarding house shouted, “Are you going to regret this?” Tomás stared at her.

“My only regret is that they’ll never know what it’s like to be loved the way I love my wife.” He turned back to the serif. “We’re done.” Patterson nodded. Married. Complaint dropped. Tomás helped Nora into the wagon. Before they drove off, he stood on the seat so everyone could see him. One more thing: whoever insults my wife insults me. Whoever threatens her threatens my family.

His voice was icy, and I protect my family. Don’t forget that. He started the car. The drive home was silent. Tomás’s hand covered Nora’s face. “Mrs. Aes,” he said softly. She looked at him. “What?” “I just wanted to say it.” Nora smiled through her tears. “I like the way it sounds.” At the ranch, the sun was turning golden. Tomás put her out of the car. Then he took Gres. They stood on the porch watching the sky change.

“Are you happy?” he asked softly. Nora looked at this man, broken by grief, who had loved again, who had chosen her when the world said she wasn’t worth it. “I am happy.” Tomás settled Grace in his arms and hugged her. “That’s good, because I intend to spend the rest of my life making sure you stay that way.” Grace shifted.

“She’s beautiful,” Nora whispered. “Like her mother.” Tomás kissed her forehead. Both of them. Inside, the house was warm, dinner was ready, the fireplace was lit. Outside, the ranch was alive. Two broken people found themselves whole in each other. A dying baby found life. An angry man found peace. A ashamed woman found courage. Together they built something the town couldn’t destroy.

A family. When the stars came out, they sat on the porch with a cow between them. Tomás took Nora’s hand. We saved each other. Nora leaned against him. We were saved. They remained silent as night fell.

Two people the world said weren’t enough, who met and discovered they were.

News

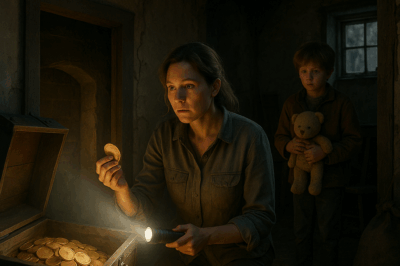

MY HUSBAND ABANDONED ME AND OUR SON IN HIS BROKEN-DOWN SHACK — HE NEVER IMAGINED THE GOLD HIDDEN UNDER THE FLOORBOARDS.

“Do you really think this place is suitable for living with a child?” My gaze shifted to the sloping walls…

A billionaire discovers a poor girl crying by his son’s grave — and the truth stuns everyone…

Multimillonario Encuentra a una Niña pobre llorando en la tumba de su Hijo — la verdad cambia todo …

The True Meaning of Service: Officer Walker’s Moment of Compassion That Restored Faith in Humanity”

In moments of crisis, we often look to authority figures to restore order and protect us from harm. But what…

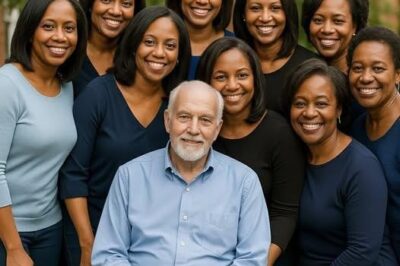

A Legacy of Love: How One Man’s Courage Changed the Lives of Nine Little Girls

In 1979, Richard Miller’s world was torn apart. The love of his life, his wife Anne, had passed away, leaving…

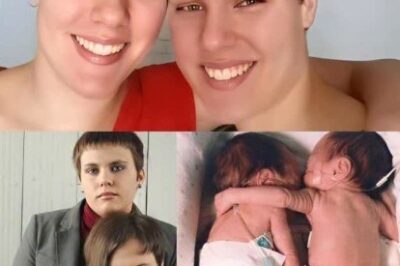

In 1995, in Massachusetts, twin sisters Kyrie and Brielle Jackson were born 12 weeks premature, each weighing just over two pounds. Initially placed in separate incubators to minimize infection risks, Kyrie showed steady improvement, while Brielle’s condition deteriorated rapidly—her skin turned bluish-gray, her heart rate plummeted, and her breathing became erratic.

In a world dominated by cutting-edge medical technology, one might think that the key to survival for premature infants lies…

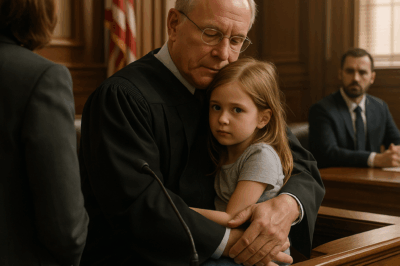

A Shield of Courage: The Unlikely Hero Who Gave a Little Girl the Strength to Speak

In the cold, sometimes impersonal world of the courtroom, there are moments that pierce through the harshness, reminding us of…

End of content

No more pages to load