WHITE MAN’S LAND

The sun hammered the borderlands between Chihuahua and Sonora, turning the noon sky to white metal and the sand into a skin of powdered glass. A north wind came in filaments and lashes, combing needles of grit across the open plain.

Don Mateo Salvatierra rode through it like a ghost on an old dun horse, the dust freckling his boots and eyebrows, his eyes half-folded against glare and memory. He was looking for a lost heifer and not expecting to find it. Men who have buried their miracles learn to look without hope.

That was when he heard the sound—thin as a cracked reed, a woman’s moan caught in the thorn. Mateo reined in and tilted his head. The wind paused, listening too. The sound came again, high and fractured, from beyond the prickly pears twisted like fists. He turned the reins and urged the horse toward that ghostly thread of voice.

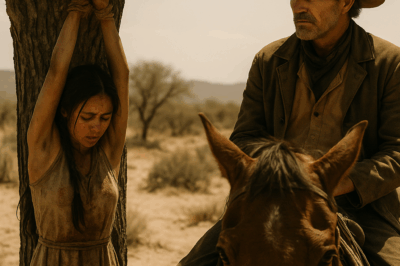

He came upon a mesquite clearing, the only shade for a quarter mile. Under its net of branches hung a small body, wrists tied and thrown over a limb, feet skimming the dirt. Black hair curtained a young face. Blood and dust had matted together on her skin. A braid brushed against a plank of wood nailed into the trunk with a rusted knife. The letters were scored deep and crude:

WHITE MAN’S LAND. NO MERCY.

Mateo swung down. His breath went tight and hot. He approached the tree the way a man approaches his own grave, knowing what he will see and not ready to see it. The girl was light as hunger and half-gone, her lips split by the sun, veins in her forearms raised like cords strained to snapping. Her eyelids trembled, stubborn on the edge of the dark.

He drew his bone-handled knife. The blade was steady, his hand wasn’t. What if this was a snare? What if men sat with rifles in the heat shimmer, waiting for mercy to reveal itself? What if this board wasn’t warning but bait?

A flash of his daughter’s face finished the thought—dark eyes, young eyes, a smile he had failed to stand between and harm. Mateo raised the knife and with a single stroke sliced the rope. The body fell—and he was there to catch it, more reflex than plan. She weighed almost nothing, as if suffering had shaken loose her soul.

He carried her from the hard noon and into the sliver of shade, spilled water onto a kerchief and touched it to her mouth. She shuddered, swallowed, did not wake. “Girl,” he murmured, a voice so low even the wind couldn’t steal it, “we ain’t all the same.”

The wind hushed, as if to listen. In that forsaken corner of land, a man and a stranger shared something stronger than fear—the first small spark of a common fate.

—

The Salvatierra place had once been a waystation and even memory had given up on it. An adobe house crazed with cracks, a tired corral, a well that could feel its own bottom—these were his holdings. He brought her at dusk, slid her down from the saddle like a broken promise he meant to mend, and laid her on the cot by the ashes of the fireplace.

He unwrapped the blanket. Her shivers were not from cold but absence. Rope burns cuffed her wrists and bit her ankles; her hands were swollen; her face was a map of dust roads. Mateo set a small fire going, cooked ground corn into a thick stew, and kept his eyes on her like a shepherd guarding the last lamb.

He drew two buckets from the well, warmed water in a dented pot, and, armed with a clean cloth, knelt beside the cot. His hands worked slow and ceremonial, washing her feet—small, hard feet, marked by distances and denial. He dabbed and pressed so gently it seemed he feared wiping away what remained. He did not speak; words are poor medicine for a soul that’s been cut.

Eventually she opened her eyes. They were big and dark with the wild in them. He stepped back, held out a tin cup. She stared as cornered deer do, then sipped. “No one’s going to hurt you here,” he said. She closed her eyes and let sleep pull her down.

That night, Mateo sat by the window and told the stars something he’d not told anyone: the girl needed a name. A person without a name becomes a shadow, and shadows get forgotten. “Nayeli,” he whispered to himself. “Come with the moon, speak with your eyes.”

In the morning her glance had less blade and more shield. She saw the bowl on the table, the clean cloth, the man outside stacking wood as if her presence had not tilted his world. She did not run. Not yet. When he offered water, her fingers brushed his as she took it. A flicker of contact that said more than a heap of words.

He did not question her. He mended fence rails, sharpened knives without hurry, checked the horses. Every now and then he leaned in the doorway and, if she was awake, gave a nod. And every night there was a full cup by her bed, always fresh.

One midnight the colt blew hard a warning. Mateo pulled on his boots and slipped out with his rifle. Tracks dented the dust around the corral—boot heels big and deep. Not his. By the well, cloven signs of a horse stopping, turning back. The night showed him nothing but its own darkness and a coyote’s complaint. He went back inside. Nayeli was upright on the cot, eyes wide as if she had known his discovery in her sleep. “See anything?” he asked. She shook her head, but the alertness had returned to her like a knife hidden in a dress.

Two days later, trouble rode in openly. Five men in worn federal uniforms slid to a halt under the mesquite. The scarred one with a hat brim like a horizon did the talking. “Buenos días,” he said in a voice that cut. “We’re after a fugitive. Comanche girl. Dark skin, long hair. Wild eyes. Mean as the desert. You seen anything unusual?”

“Land. Stock. Silence,” Mateo said. It was as much truth as he owed. The scarred man studied him, swung down, walked a circle that put his shadow across the house door. “You live alone.” Not a question.

“For a spell,” said Mateo.

“We’ll take a look.”

“You already are.”

Silence got thick enough to slice. The scarred man spit, remounted. “Aid a fugitive and there’ll be consequences.”

“Hunt the innocent,” Mateo said, voice dropping like a stone into deep water, “and there’ll be the same.”

They rode off in a boil of dust. From the window, Nayeli had watched without breathing.

That night, when he set a bowl before her, she took it sitting straight-backed, eyes meeting his. She nodded once. It was the first bridge built between them. He called it trust.

—

At sundown he found her behind the house, crouched over the earth with a twig. She was drawing, and the lines had a precision that was almost pain. A bird. Not just any bird—wings flung open in the exact right angle of flight, body wrapped in tongues of flame. Fire not as ruin but as sacrament.

Mateo’s chest pulled tight. He knew this bird. He’d seen it cut into a rock face near the Río Grande and again in an army report. The Firebird—the sign of the Fallen Sun clan, outlawed by men who used knives for erasers.

Nayeli did not see him watching. When she had finished the bird, she sat facing it as if in prayer. Mateo crouched beside her and let the silence hold them both.

“I did not steal,” she said at last, voice raw from disuse. “I did not lie. I only lived.”

He turned to her. Those words cost blood to lift. “I only lived,” she said again, softer. “And they hated me for it.”

The dam behind her ribs cracked. The first tears came quiet, then the sobs arrived and shook her thinness like wind shakes dying corn. Mateo did not reach for her. He set his hand down on the ground beside the bird’s wing—his palm, her flame, a simple vow.

She looked at him through the blur. For a moment there was no white rancher and no Comanche girl—only two bones carved by loss. They stayed as sunset bled into the dirt. Under the red light, the bird seemed to lift from the soil.

For once no one asked her, What did you do? Why are you running? Someone sat and listened to her silence and counted it sacred.

By full dark they went inside. Nayeli didn’t slip in behind him like a shadow; she walked next to him. She didn’t speak again that night. She didn’t need to. A voice freed from fear is a river—no chain can hold it long.

—

Rumors ride faster than horses. In Chaparro’s cantina, in Agua Prieta’s card rooms: Salvatierra the silent has a Comanche girl hidden at his place; a braided figure at his well; Mateo—who buried wife and daughter with his bare hands—now defies the world by refusing to bow.

One clouded morning six riders arrived. Not in uniform, but their boots were polished, and their arrogance wore pistols like jewelry. The leader with a thin mustache drew rein under the porch. “Don Salvatierra,” he called nasally, “we’ve come for something simple. Folks say you’re harboring a wild creature. Feed it, clothe it, hide it. We don’t want trouble—just justice.”

“Search,” Mateo said. “The world here is small.”

They turned over the stable, peered down the well, rapped on the shed wall. They did not think to pull up the floor of the old grain cellar, where sacks of corn hid a trapdoor and a girl’s breathing. Finding nothing, the man with the mustache came back, smiling with his mouth and not his eyes. “Compassion’s a virtue, Don. Compassion for certain creatures will crush you. Those who shield the enemy become the enemy.”

Mateo let his gaze rest on the dust where the hoofprints had already started to soften. He did not reply.

That night, when the wind carried the taste of war, he dragged an old trunk from under his bed. Letters torn. His wife’s handkerchief. And the board from the mesquite: WHITE MAN’S LAND. NO MERCY. He had kept it as a lesson held at his own throat.

He built a small fire behind the house and fed the board to it. The letters blistered, blackened, and fell into embers. “Let what divides us burn,” he said. “Let what bars us from love burn.”

The back door opened softly. Nayeli stepped out barefoot in a dark shawl. She moved to him and, without words, took hold of his coat with both hands. It was a gesture like a child’s—simple, absolute, and braver than shouting.

He set his hand over hers and did not remove it. They watched hate turn to ash. For the first time, she chose light instead of the hiding dark.

—

At dawn he said, “We must leave.” She lifted her face. “South,” he said. “We’ll cross the river. There’s a valley beyond where patrols don’t ride. Lipán, Tobosos, some Comanche keep to that land. They live as before.”

She looked at her hands as if deciding her fate, then up at him, mouth shaping syllables he had not yet earned. “Shimana,” she breathed—then in soft Spanish, “I want to live. I want to live… as your woman.”

Something in his chest split to make room for light. He took her hands and nodded once. No ring, no vows. A decision already made by two stubborn engines of will.

They packed what little remained: water, salt, blankets, a few tools, a pouch of colored beads—her last inheritance. Mateo tore two doors from the old stable to rig a travois, braided new straps for the saddle. They rode into the heat-shimmering evening, a skin of dust thrown over their backs like a benediction.

Near midnight the mountains rose like a prayer. “There,” he pointed, “a slit between rocks no soldier finds.” Gunfire sheared the quiet. A bullet took the packhorse, another grazed past Mateo’s ear. “Hold on,” he said, voice gone to gravel. He shoved Nayeli from the saddle to sand, planted himself between her and the night, and caught a round in the shoulder. It felt like a burning stone punched through him, but his knees held. He threw her arms around his neck and ran. Bullets hissed past like angry bees. A crease in the cliff appeared, and he fell into it with her.

Silence came back, stitched from their ragged breaths. Fingers found fingers, laced. “Sh…” he murmured. “We’re not finished. Just a little farther.”

—

A tent stitched from canvas and stubbornness went up by a small river. The sound of water against stones made a music that seeped into sleep. The wound went angry, then clean; fever burned and then abdicated. Each day Mateo’s sight sharpened, and each night Nayeli’s touch grew sure.

“Your true name,” he asked one night while the wind stroked the tent.

She set the damp cloth down, took her time, and in a voice that ran clear under her fear said, “Esana. In my tongue it means calm river.”

He smiled without showing teeth. “Then you are the quiet my storm needed.”

Weeks breathed by. Esana, fingers clever as birds, stitched small cloths with desert flowers, with stars, with the silhouette of his dun horse. A curve began to show beneath her dress. She pressed her palm to it one evening on the bank, whispered, “Hello, life. Your father is the white man who did not just shelter me—he loved me without fear.” The river, a mirror for the sky, took her words and did not lose them.

Mateo ringed her waist with his hand. They stood staring outward—water, light, a future stitched from nothing anyone else could see. That night, he led her to a little altar they had made: a worn photograph of the adobe, a charcoal sketch of a mesquite branch, a scrap with the Firebird she’d drawn. “Our story,” he said quietly, “began with hate and desertion. It will end with forgiveness and love and a promise we keep every day.”

She leaned her forehead to his breast and listened to the drum that had called her back from hanging. Moonlight crept in to find two faces and did not find fear there. They had already taught their love to walk without words.

Beyond the river and the drawn lines that men insist upon, on a nearly forgotten shore, a small family began to beat. Not an empire. Not a lineage to brag over. A brave and homely bridge thrown across old cuts. Not revenge but peace. Not loss but redemption.

Between the hiss of the water, the mutter of the wind, and the quickening beat of a womb that would soon argue with the world, Mateo and Esana became what they feared they would die without becoming: a family—memory writ with petals instead of thorns.

News

A silent rancher found a young Comanche girl hanging from a tree with a sign that read “White Man’s Land.” The sun burned mercilessly on the dusty border between Chihuahua and Sonora. It was midday, and the north wind brought gusts of sand that scraped the skin like tiny knives. Don Mateo Salvatierra, a solitary rider with a distant gaze, slowly crossed the dry plain on the back of his old horse, searching for one of his stray heifers. Dust covered his boots, and his half-closed eyes scanned the horizon with the patience of someone who has learned to live without expecting anything. It was then that he heard a moan, barely a whisper like the lament of a trail in the bushes. Mateo stopped the horse and nodded to it. He heard it again…..

WHITE MAN’S LAND The sun hammered the borderlands between Chihuahua and Sonora, turning the noon sky to white metal and…

A silent rancher found a young Comanche girl hanging from a tree with a sign that read “White Man’s Land.” The sun burned mercilessly on the dusty border between Chihuahua and Sonora. It was midday, and the north wind brought gusts of sand that scraped the skin like tiny knives.

WHITE MAN’S LAND The sun hammered the borderlands between Chihuahua and Sonora, turning the noon sky to white metal and…

A SILENT RANCHER CUT ACROSS THE CHIHUAHUA–SONORA DUST… THEN SAW A COMANCHE GIRL HANGING FROM A MESQUITE WITH A SIGN: “WHITE MAN’S LAND.”

WHITE MAN’S LAND The sun hammered the borderlands between Chihuahua and Sonora, turning the noon sky to white metal and…

When my stepchildren declared they only answer to their biological parents, I decided to give them exactly that. I changed the locks, cut off all privileges, and told their dad it was time for him to step up, pickup was tonight. The silence that followed said it all; no one even tried to argue.

“You’re not my dad. You don’t make my rules.” That was the line that broke me. I’m Mark, 42. I…

MY STEPCHILDREN SAID “YOU’RE NOT MY DAD — WE DON’T ANSWER TO YOU” — THEY DIDN’T KNOW I PAID FOR EVERYTHING THEY LOVED

“You’re not my dad. You don’t make my rules.” That was the line that broke me. I’m Mark, 42. I…

“You’re not my dad. You don’t make my rules.” That was the line that broke me. I’m Mark, 42. I married Jessica three years ago. We blended our families—my two (Emma 10, Tyler 8) and her two (Mason 16, Chloe 14). From day one I showed up: rides, homework, practices, grocery runs, new cleats, late-night sheet-pan nachos for after-game debriefs. I figured if I kept loving them like a dad, they’d eventually see me like one. I was wrong.

“You’re not my dad. You don’t make my rules.” That was the line that broke me. I’m Mark, 42. I…

End of content

No more pages to load