I walked into my husband’s office to surprise him with lunch and found him kissing another woman passionately, when I confronted him, she attacked me and kicked my eight month pregnant belly, my husband laughed, that’s when the door opened and their faces dropped…

Part One

I was eight months pregnant and walking on ankles that felt like someone else’s problem, cradling a warm sandwich in a thermal bag like it was the crown jewel of a small kingdom. Turkey and Swiss on sourdough with the sharp mustard George loved—the kind that made his eyes water and his laugh come out boyish. It was a September afternoon slick with the promise of rain; the cardiology wing of Metropolitan General hummed with purposeful bodies and the thin, tinny chorus of monitors counting seconds.

He had kissed my forehead before dawn and said, “Take care of our little miracle,” whisper-soft as if we might frighten luck by speaking too loudly. Three years of trying. Two losses that hollowed the house so thoroughly that the echo of our grief had learned our names. We had cried together in the kitchen when we finally saw two lines. He had pressed his palms to my belly and said, “I will love you both until my last breath.” He had meant it, I thought. What else is there to think when the person who knows your ribs from the inside looks at you and says, out loud, forever?

George’s nameplate gleamed under the fluorescent buzz: Dr. George Lewis — Cardiology. I touched the sandwich bag and smiled at the absurd domesticity of my errand. Dissertation chapters were piled on my desk at home—I was six months away from defending in psychology—but the afternoon felt like it could hold both the end of graduate school and the simple pleasure of togetherness. Our daughter—Mabel, we whispered at night, testing how it felt in our mouths—kicked when I knocked lightly. I expected to hear his voice—Come in, Vi—warm with the private nickname that let the rest of the world fall away.

The office door yielded under my hand.

The bag hit the carpet with a thud that sounded like a stone thrown into a well you didn’t know was there.

George was pressed against his desk, white coat open, his hands tangled in auburn hair that did not belong to me. Stacy Ryder—the new nursing supervisor with winter eyes and perfume that had made my laundry smell like a department store for months—had her legs wrapped around his waist. Medical charts, the paper scaffolding of other people’s lives, fanned out beneath them like a nest built of stolen things.

I did not recognize my own voice when it scraped the air and made them spring apart like teenagers caught in a backseat. He went pale and then red. She smoothed her skirt, lipstick smeared—her laugh, when it came, sounded like breaking glass.

“Violet,” George started, and already my name in his mouth felt false.

“Don’t,” I said. The syllable shook and then steadied. I stepped backward and the room swam.

Stacy hopped off the desk and fixed me with a gaze as cold as the tile under my shoes. “Well, this is awkward,” she said lightly, like she’d been caught cutting a line and not gutting a marriage. George shot her a warning glance, but she turned and trailed a hand across his chest, possessive as if I were the antagonist in her story.

“Stacy, stop,” he said.

“Stop telling your wife the truth?” she purred. “That you haven’t loved her in years? That you only stayed because you felt sorry for her after the miscarriages?”

Each sentence was a knife across skin I didn’t know was exposed. “That’s not true,” I heard myself say, but he just looked at me with pity—an expression so much more cruel than anger I could hardly breathe.

“Did you really think,” Stacy went on, as if she’d been given the floor and had a script to finish, “that a man like George would be satisfied with someone like you? Look at yourself.” She gestured at my body. “Swollen, waddling. When’s the last time you even saw your own feet?”

“George,” I said, my voice breaking from somewhere beneath the weight of everything, “tell her to stop. Tell her she’s lying.”

He looked at the carpet.

“Your husband hasn’t been your husband in any way that matters for a long time,” Stacy said. “He was with me the night you had your little false labor.” She leaned in, her perfume turning the air into something I had to choke down. “He says you cry over every little thing and he wishes he’d never—”

“Enough,” George said, but it was limp, a cardboard word in a house on fire.

“Eight months,” Stacy said, satisfaction bright in her eyes. “Do the math.”

Eight months. The same age as the child under my hands. I felt something inside me straighten. “Move,” I said, when she blocked the doorway. “Get out of my way.”

“Or what?” she taunted. “Run crying to your uncle about how the other kids are being mean?”

Ice shot through me as she smiled. She knew. Of course she knew. Uncle Elliott had gotten me the volunteer gig years ago that turned into the third date where George had told me I’d change the world. He had walked me down the aisle because my father couldn’t stop being afraid of commitment, even in the best of hours. Elliott was medical director at Metro General; he would not save George from what George had chosen.

“Stacy,” George warned again, his voice a shade darker.

She whirled and snapped, “Am I going too far, or am I finally telling her the truth?” She turned back to me, inches away. “Your husband doesn’t love you. Your marriage is over. Frankly, looking at you now, I can’t blame him.”

I did the most human, most foolish thing: I tried to push past her. She struck like a snake—hands hard against my shoulders, surprising strength in that compact body—and I stumbled, gravity winning before thought could. My side hit the floor; instinct pulled me into a protective curl.

“Stay down,” she hissed, and then she raised her foot and drove it into my belly.

Pain is not a word that belongs here. There are only white edges, a ripping redirect of reality, all of me collapsing into a single thought: Mabel. I curled around the place she was, panting, as Stacy drew her leg back again—

“Stop!”

The voice that cut through the office wasn’t George’s. It was deeper, command layered into concern, the voice of triage and decades of telling men to wash their damn hands.

“What the hell is going on?”

Uncle Elliott stood in the doorway, his rage a controlled blade. Behind him, two nurses stuttered to a halt, expressions flipping from confusion to horror. Stacy staggered backward, her face draining toward ash.

“Director Stenson,” she breathed, grasping for professionalism the way drowning people grab for shirts.

“Explain,” he said, crossing the room to kneel at my side. His hands were gentle on my wrist. “Call a trauma team,” he told the nurses. “Now.”

“Uncle—” I gasped. “The baby.”

“Don’t move,” he said, calm and absolute; I obeyed because the part of me that had been eight years old and scraped her knee believed he could fix anything if I held still long enough.

“Violet,” George said from somewhere above me, his apology scraping its way across air, “I didn’t—she—”

“Shut up,” Elliott said without looking up, so cold the room frosted. “Both of you.” He glanced at the doorway. “Security. And someone call 911.”

Liquid warmth spread between my legs. Too soon, my body told me. Eight months is a line and we were stepping over it. “The baby’s coming,” I whispered, terror barreling through grief and fury. “It’s too early.”

“We’re going to take care of you,” Elliott said, squeezing my fingers in a way that made me anchor to those two inches of skin. Sirens got louder. Nurses got lower. Hands lifted me like I was both fragile and heavy.

As they wheeled me past George, he pressed himself into the wall. I turned my head and looked at him—at the man who had whispered “our little miracle” into my hair that morning—and promised my daughter I would build a world where she didn’t spend her adult life trying to please someone who preferred winter.

Mabel came like she fought: stubborn and furious and soft enough to make even my uncle cry when he thought I couldn’t see. Four pounds wrapped up in tubes and determination; she blinked at me from the NICU incubator as if to say, I wasn’t done with the dark yet but I’ll try the light if you’re here. Dr. Beckham—kind hands, steady eyes—kept saying “small but strong” and updating me on lungs, on vitals, on numbers that became a second language for hope.

In recovery, Elliot stood at my bedside, his suit wrinkled for the first time in memory. “I’ve suspended both George and Miss Ryder,” he said, each word clipped. “And I’ve referred this to hospital legal.”

“Suspended,” I repeated, the syllables cotton in my mouth. “Assault—”

“Violet,” he said, low enough that it felt like we were under a blanket in the living room and not in a corridor that smelled like antiseptic. “What I saw is a crime. The rest will follow.”

In the hallway, George began pleading with someone, the desperation in his voice like a violin string pulled too tight.

“If either of you comes within fifty feet of my niece or her daughter,” Elliott said into the corridor, voice carrying like a law, “security will remove you permanently. And then the police will pick up where they left off.”

Their footsteps retreated.

I did not sleep that night. Every time I closed my eyes, I saw Stacy’s face bent toward my belly, heard her foot connect, saw my husband watch. My phone buzzed. Gina—my older sister, red hair, litigator’s spine—had sent a text from O’Hare: On my way. Don’t sign anything without me.

Gina flew in at eleven, storm wind in heels, and gathered me into her arms like a mother bird. “Have you seen her?” I asked. “Mabel?”

“She’s perfect,” Gina said, eyes bright. “Tiny, but bossy. Like you.”

I told her everything, because she asked and because what else do we do, we women, but make sense of the unspeakable by giving it words? When I finished, she sat back, jaw tight, and said, “We’re going to ruin them.”

“I just—”

“You want what?” she demanded softly. “To forgive? For the sake of the baby? Vi, some bridges are bridges and some are one-way planks over ravines. You don’t go back.” She was already scrolling through her contacts. “I’m calling Melinda.”

Melinda Florence showed up the next morning in a gray suit and a face that combined the kind of empathy that lets kindly mothers trust you with their finances and the kind of sharpened intelligence that makes executives cry in depositions. She had already read the initial police report.

“Miss Ryder has been charged with assault and battery,” she said, setting a thick folder on my tray table. “Enhanced penalties because you were pregnant. As for your husband: adultery, abandonment, emotional distress. That’s civil. Criminally…” She flicked a glance at Elliott. “We will see.”

“What do you need from me?” I asked.

“Resolve,” she said. “Documentation. And a camera-ready face you can keep for reporters. This case has teeth.”

Three weeks later, Mabel and I went home to a house that hummed with grief even in its paint. Gina had moved in; she made lists and installed security cameras and convinced me to hire Rosa, a nanny with a military police background and a soft spot for orphaned kittens. Gina documented every text from George (“please,” “explain,” “you owe me,” “for Mabel,” twenty-seven variations on the theme of let me back in). Melinda came and went with updates and a smile that looked like a verdict.

Then Gina found a life insurance policy in a stack of bills. Two million dollars. Taken out on me six months earlier. My name was spelled correctly and nothing else made sense.

“Did you know about this?” Gina asked, her voice as calm as a courtroom. I shook my head and tasted bile.

We counted backwards and the math made a shape I recognized from nightmares. Over the next few days, Melinda’s contacts at the FDA tested everything in our house that had passed through George’s hands. Herbal tea? Misoprostol, trace levels. Vitamins? Something else that nudged a uterus toward expulsion if a baby was a stubborn lodger.

“Attempted murder,” Melinda said into the phone, not unkind, and my legs gave out like a puppet with its strings cut. “Insurance fraud as motive. Conspiracy with Miss Ryder. The prosecutor will add charges.”

The arraignment was a theatre we had no choice but to attend. George stood in a suit I’d picked out for him two years earlier when I still believed he would keep promises with his hands and not just with his mouth. He pled not guilty; he always had such a way with sentences. Stacy stood in a county-issue jumpsuit; she was smaller without the armor of cosmetics. She pled not guilty, and for the first time she looked like she was thinking ahead and not just in the present tense of pleasure.

When reporters swarmed, Melinda put a hand on my elbow and practiced her no comment in a tone that keeps cameras polite. Something in me refused to be a photograph without words. I lifted my chin and said, “He tried to kill me and our daughter for money. She kicked me on the floor to finish what drugs couldn’t. We survived. Now we do the part where they don’t.”

That night, the phone rang. A woman named Sarah Chin whispered into my ear at midnight like a character in a thriller you would have told was overwrought if you hadn’t lived it.

“I used to work surgical inventory,” she said. “Stacy framed someone. Dr. Beckham. She planted evidence to destroy her. She had help.”

We met in a coffee shop across town. Sarah was small and shaking, and she set a manila folder on the table like it was a thing that might explode.

“She seduced Dr. Beckham’s husband,” Sarah said. “Then she made it look like Dr. Beckham was stealing medications. I signed forms I didn’t understand. I thought it was a count. It was a setup.”

I saw Dr. Beckham’s face in my mind, gentle and focused as she caught Mabel like a gift. “Will you testify?” I asked. Sarah nodded, and the waitress set down more napkins than any woman needs for tears.

Evidence begets evidence if you give it room. Stacy had a pattern; Melanie had a name for it. Melinda compiled, cross-referenced, built timelines that thread through our days. The prosecutor added charges. Dr. Beckham was located and she told about a husband who had learned to lie before he learned to stop. The hospital found a spine it had mislaid under a century of protecting men who made money and punished women who made sense.

And then Rosa came into my kitchen with a courier envelope that smelled like a printer and bad news. Inside: a photo of George and Stacy and a man I recognized from the evening news—Vincent Caruso, a walking rumor about organized crime. The note was typed: He owes money. The policy wasn’t about romance. It was about your death. A friend.

The FBI agents who sat in Melinda’s office explained calmly, as if they were telling me about traffic patterns. “He owed almost three million dollars,” Agent Santos said. “He laundered money through fake medical equipment purchases. The insurance payout would have saved his skin.”

“If we could put rope around their words,” she added, “we could tie this all down.”

So I wore a wire and walked into the house where I had painted a nursery pale yellow because we wanted to be surprised by more than betrayal. George looked haggard and hopeful; my disgust had a kind of pity’s outline for a second and then I put it down. I stood by the table while he said things men say to women they have underestimated: I never meant and I was trying to protect us and they made me and we could still.

He admitted the misoprostol; he called it “medicine to help.” He admitted the policy; he called it “prudent.” He admitted Caruso without naming him; his eyes did that. He admitted Stacy’s usefulness; he called it “unfortunate.”

And then he lunged.

He is bigger; I am the mother of a premature miracle. That plus Rosa’s fists in a gym three mornings a week equals a knee in his stomach and a gasp that sounded like a confession.

“FBI!” Agent Santos shouted as the front door exploded into competence. They read him his rights; there is poetry to be found in men hearing sentences that aren’t their own.

As they cuffed him, he looked at me—the woman who had brought him a sandwich and years and a child and a whole heart—and said, “This isn’t over.”

“Actually,” I said, too tired for anger, “it is.”

Part Two

Court is architecture. You build with testimony and paper and the way a man looks when you ask him where he was when his wife went into false labor.

George’s trial made the local news, then the state news, then the shows where people narrate other people’s lives after dinner. Melinda put me on the stand and said, “Tell the truth,” and I did. Dr. Beckham told about a career Stacy had hollowed out in two months. Sarah told about signing papers with hands that didn’t stop shaking after. Elliott told about my blood on a white floor. The lab tech told about misoprostol in tea. The FBI told about Caruso. And then Caruso told about George.

“We told him to handle his business,” Caruso said, every inch of him boring like a banker and twice as uninteresting. “As long as we got our money.”

The jury didn’t take long. Guilty, guilty, guilty. Insurance fraud. Attempted murder. Money laundering. Racketeering. Conspiracy. The judge—who looked like she’d raised three sons and a nonprofit—gave him thirty-five years and told him that people who treat women as collateral do not get to say goodbye to their children with the same lips they used to ask for mercy.

Stacy’s trial felt like an audition she couldn’t quite master. She cried. She dabbed. She told about being manipulated by a charming doctor, about wanting to protect a man from a wife who hoarded grief. The jury listened the way cats listen to vacuums: politely, from a distance. Guilty on assault, conspiracy, evidence tampering. Fifteen years. The judge read a line that stuck in my ribs: “Calculated cruelty.”

All the while, Mabel grew. She gained cheeks and a habit of staring at you as if she is listening for lies. Rosa taught her to kick; Elliott taught her the names of bones. Gina taught her to shout “objection” when she didn’t like vegetables. I taught her that pain doesn’t make you interesting; survivorship does.

George wrote letters Melinda filed in a box labeled with a single word: Exhibit. I did not read them. Caruso went to prison for twelve years and the news moved on. Metropolitan General instituted new hiring practices and old apologies.

I finished my dissertation on trauma and growth and the way women make scaffolds out of their own hands when no one else will hold them. The committee asked me questions I had answers for because my body had been the case study first. They shook my hand and called me Dr. Violet. I stood in a lecture hall in a jacket that made me feel like armor and told a hundred students that survival is not the end. It is the foundation.

Gina sat in the front row and cried in a way that makes redheads look like they are on fire in a good way. Elliott bounced Mabel in the back until she announced to the row in front, “My mama is a doctor now,” and the row began to cry too.

Afterward, we went to the campus coffee shop where Dr. Beckham held my daughter and told me that she had gotten her license back. Sarah Chin joined us with hands that still trembled slightly when she signed receipts. We did not toast with champagne because life does not always look like a movie; we raised paper cups and drank lukewarm coffee and called it justice.

The hospital settled a civil suit quietly, the way institutions do when they realize that their risk assessment had zeroed out empathy. The money paid for lawyers and locks and grad school I didn’t have to think twice about. The best part built a victim advocacy program in Metro General’s basement with a sign that says You Are Not Alone. We put couches there that felt like hugs and a lawyer’s office that looked like a friend’s kitchen table and a closet full of shirts for people who had wrapped themselves in hospital gowns and shame.

Rosa stayed on as head of security for my side hustle—my practice, where women come with the kinds of stories that sound like fairy tales if fairy tales told the truth. We change locks and file petitions and put cameras in hallways and teach a class my sister named Boundaries 101: No is a Complete Sentence. We take calls at 2 a.m. because that is when your brain decides you can’t do it and a voice tells you, you already did.

Two years after George tried to smother my life with a pillow full of money, I stood at a podium with a different kind of microphone. Behind me, a screen showed a slide that read Post-Traumatic Growth. In the front row, a mother I’d helped last year rocked a baby who slept with his mouth open. Rosa stood in the back with her arms crossed and a look that could stop time. Gina slipped me a note that said Remember to breathe.

I told the room about Mabel’s birth and the way one woman’s foot can become the last thing you see if another man’s hand refuses to move. I told them about the binder my grandmother kept, and about the way paperwork is a kind of weapon when you are not allowed to carry a different kind. I told them about the night I wore a wire and then took it off and put it in a baggie labeled Exhibit A because some endings are neat if you force them to be.

I told them what nobody ever told me at twenty-three: that love is not supposed to feel like vigilance, that family does not make rules you must break your back to follow, that money is not a moat for men to hide behind while women drown.

When the questions were over, a woman waited on the edge of the crowd with eyes that looked familiar and the brace of someone on a cliff. “My husband,” she said. “He—”

“Sit,” I said, pointing to a chair. “Let’s start with your name.”

Later, on the walk back to my car, Mabel in a rainbow sweater, Elliott insisting on carrying the diaper bag because his back was still better than my pride, Gina telling Rosa dinner plans like it was a military op, I felt the kind of quiet you get when the doctor who delivered your child comes to your talk and sits in the second row and laughs in the right places. The sunset had the decency to show up like a cliché and I didn’t hate it.

George will be eligible for parole when Mabel is twenty-seven. I do not plan around that. I plan around Mabel’s third birthday and my students’ midterms and a grant proposal that might fund another staff attorney for the center. Sometimes at night Mabel puts her little hand on my face and says, “Mine,” and I say, “Yes,” and think of how she almost wasn’t, and how she is, and how beautiful that triumphant contingency is.

We survived. We built a life that does not require anyone’s laughter or approval to stand. We learned the difference between revenge and justice: one tastes like heat, the other like clean water. Some days we drink both.

Our little miracle goes by Mabel in public and by “boss” when Rosa doesn’t think I’m listening. She is ferocious; she likes stethoscopes and toy police cars and a doll she has named Enough. She is not careful with her heart and that is fine because that is not her job. It is mine.

I still take sandwiches to hospitals sometimes. Turkey and Swiss on sourdough with mustard that makes you cry. I walk down hallways that beep and smell like bleach and tell young fathers to wash their hands. I say my daughter’s name out loud like a charm.

Once, in the cardiology wing, a doctor with winter eyes rounded a corner and stopped when she saw me. Her mouth tightened. Her scrub pants had prison creases in the woman wearing them now but not back then. There are some women you do not forgive and you do not forget; you simply make sure you never let them within fifty feet of your family.

I adjusted Mabel on my hip and kept walking. Outside, Baltimore—or maybe it was Minneapolis in my memory—tried to rain and failed. The air smelled like metal and beginnings.

The nightmare ended in a courtroom. The rest of my life began in a NICU and a classroom and at kitchen tables where women tell me the worst thing that ever happened to them and I tell them about paperwork and pepper spray and how to monetize fear into fury and then into structure.

My husband laughed while his mistress kicked me. Their faces dropped when the door opened and my uncle stepped in with the kind of love that makes commands sound like lullabies. That was the beginning of the end for them, and the beginning of the beginning for me.

I kept my promise to my daughter that day on the floor: this wasn’t over. Not by a long shot. We ended what they started. And then we built something they never could have imagined.

END!

News

My daughter-in-law slapped me in the face and demanded my house keys! CH2

My Daughter-in-Law Slapped Me in the Face and Demanded My House Keys! Part One The slap landed before I…

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing. CH2

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing …

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down The Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything. CH2

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down the Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything Part One My…

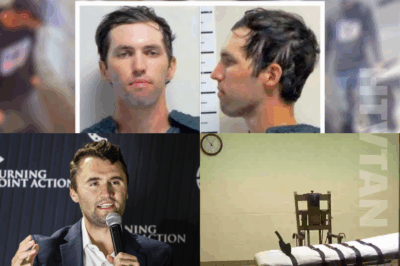

Suspect In Charlie Kirk Killing Could Face The DEATH PENALTY — Utah Signals An AGGRAVATED Murder Case

Prosecutors booked 22-year-old Tyler Robinson on aggravated murder, a charge that opens the door to capital punishment under state law….

“We will find you, we will try you and we will hold you accountable to the furthest extent of the law. And I just want to remind people we still have the death penalty here in the state of Utah.”

Utah Governor Spencer Cox Issues STARK WARNING — State STILL Has The DEATH PENALTY As The Charlie Kirk Case IntensifiesHours…

SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME “YOUR CHILDREN ARE MINE.”

“SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE” MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME—‘YOUR…

End of content

No more pages to load