October 23, 1942

Somewhere west of El Amamein — “Hell-on-Earth” to every American who’d been there

The night didn’t start with fire.

It started with hope.

Staff Sergeant James “Jimmy” Grant stood beside the squat M3 medium tank everyone in the company called Porkchop, one hand on the clammy armor, and listened to the desert breathe.

Far to the east, British guns were warming up—dull, distant thumps rolling across the sand like somebody slamming doors in a giant, angry house. The sky was as black as the inside of a radio set, the stars sharp and cold, but the horizon flickered now and then with faint, reddish blurs.

“Biggest barrage since the last war,” Lieutenant Harlan said, stamping his boots, breath white in the chill air. “That’s what they’re saying, anyway. Monty’s gonna blow Rommel clear into the Mediterranean.”

Jimmy grunted, eyes on the stubby whip antenna bolted to Porkchop’s turret. The thing quivered every time the tank’s engine coughed. In the faint light of a hooded lantern, it looked thin, frail—and, he knew from experience, next to useless when the shooting really started.

“I’ll believe it when our boys can hear each other past five hundred yards,” he said.

“You always such a ray of sunshine, Grant?” Harlan asked.

“When the radio works, sir? I’m a regular Fourth of July.”

He didn’t say what he was really thinking, because nobody wanted that kind of honesty before a battle: We’re blind as bats in steel coffins, and the Germans aren’t.

He’d seen it play out again and again across the North African sand.

The Americans were new to this desert war, but they’d joined late to a bad pattern. The British had already burned through thousands of tanks in these wastes—Shermans, Grants, Crusaders—left smoking on dunes, their crews buried nearby in shallow graves that filled with sand.

On paper, the Allied machines were good. Sometimes better than the German Panzers. The Army liked to brag about it. Big engines, decent guns, tough armor.

But on the battlefield, it never seemed to matter.

The problem wasn’t guts. Hell, Jimmy had met more guts than common sense in every armored outfit he’d ever seen.

The problem was that every American and British tank fought like it was alone.

And the German tanks… didn’t.

Jimmy had heard the stories from British crews around the maintenance depots. You didn’t have to be a genius to see the pattern. Panzers sliding and pivoting like they were linked by invisible wires, reacting to every shift in the fight. Allied tanks, by comparison, blundered forward, radios hissing with static, commanders screaming into headsets that might as well have been tin cans on a string.

“Grant!”

He jolted. Lieutenant Harlan was watching him.

“You with us, Sergeant?”

“Yeah,” Jimmy said. “Just thinking about the interference, sir.”

“The engineers back home say it can’t be helped,” Harlan pointed out. “Metal hull, engine noise… it’s the physics. That’s what the reports say.”

Jimmy snorted softly. “Physics never held a soldering iron, sir.”

Down the line, engines coughed to life one by one. Somewhere, a runner tripped over a fuel hose and earned a string of curses in three different accents. The American 5th Armored Battalion was lashed to a British division for the night’s operation—Montgomery’s grand offensive, with an American garnish.

Orders had filtered down the usual way, passed from map table to battalion to company to platoon, changing flavor each time like cheap coffee refilled in the same pot.

At 2200 hours, advance. Tanks in line abreast. Follow artillery creeping barrage. Maintain radio contact.

Maintain radio contact. Jimmy almost laughed.

He patted Porkchop’s antenna one more time and ducked back into the maintenance tent. On the workbench lay the thing that had been haunting his spare thoughts for months: a mess of copper wire, a modified mounting bracket he’d scrounged from the scrap pile, and a notebook full of diagrams.

It looked like nothing. Less than nothing. A stupid idea.

But the numbers in his notebook whispered something else.

“Sergeant!”

The shout came from the lane between the tents. Corporal Henley, one of Porkchop’s crewmen, materialized in the flap, helmet tilted back on his head.

“You done arguing with the laws of nature?” Henley asked.

“Not yet,” Jimmy said.

“Well, argue faster. We move in twenty.”

Henley disappeared. Jimmy exhaled, long and slow, and stared at the bracket.

He could picture the battle already: tanks advancing into a wall of artillery smoke, enemy fire stabbing back through the haze, commanders shouting into radios that answered only with static. Confused movements. Friendly tanks blundering into each other’s fields of fire.

He’d seen it too many times. He’d watched too many wrecks dragged back to the depot, their radios intact and useless.

The experts—big brains from MIT and Harvard and the Signal Corps labs back in Jersey—had explained it in fat technical manuals: Faraday cage. Engine interference. Improper antenna lengths. Tanks were metal boxes on tracks. Metal boxes ate radio signals. That was that.

Unsolvable, they called it.

Jimmy had never trusted that word.

He picked up the modified bracket, ran his fingers over the small holes he’d drilled through it, feeling every edge.

He had a theory. A crazy one. A theory that said a tank didn’t have to be a prison for radio waves. It could be part of the antenna instead. The whole hull, a resonant system, if you tied it in just right.

It was stupid. It was genius. It was both.

And according to regulations, it was absolutely forbidden.

Any modification to standard radio gear required approval from technical boards, forms in triplicate, signatures from people who’d never had sand in their boots. Unauthorized changes could get a man busted down or shipped home in disgrace.

Jimmy looked toward the sound of revving engines.

His hands moved almost before his brain reached a decision.

He grabbed his tools, the bracket, the coil of copper wire, and headed for Porkchop.

James Grant hadn’t set out to argue with the United States Army.

Growing up in a nowhere Ohio town during the Depression, his ambitions had been modest: fix things, keep them running, maybe one day own his own repair shop with a faded “RADIO SERVICE” sign hanging over the door.

His dad had worked at a Ford plant until the layoffs. His mom ran a sewing machine until the light got too bad to see. Jimmy found his place early on, huddled over busted Philcos and Zeniths neighbors brought by, coaxing music and baseball games out of silent boxes.

College was for other people’s kids. He’d enrolled in a night course at the local technical college, then dropped out when the money ran out. But what the rich boys learned from textbooks, he learned by burning his fingers on hot solder and rewinding coils until his eyes crossed.

When war came, the Army had taken one look at his pre-induction tests and said, “Congratulations, son, you’re going to be a radio man.”

He’d raised his right hand and ended up in the guts of armored vehicles.

On paper, he was a technical sergeant in the Signal Corps, attached to 5th Armored Battalion. His day job was fixing the SCR-508 sets crammed into the steel bellies of Shermans and Grants—cracking open chassis, swapping out tubes, checking voltages, cursing at engineers who’d never tried to pull a chassis in a space this tight.

The work was steady, dirty, and about as glamorous as changing truck tires.

But it put him right where the problem lived.

He heard the complaints from crewmen after every battle. The stories were always some variation of the same nightmare: We went in, we tried to call, nobody answered. We didn’t know who was where. Then the shells started landing and…

He’d seen good tanks burned out not because the armor failed, but because somebody took a wrong turn into friendly artillery while their radio screamed static.

At first, he’d blamed the equipment. Maybe the sets were lemons. Maybe the cables were junk. Maybe the masts were defective.

So he’d tested. Measured. Swapped radios between tanks. Replaced cables. Tried different grounding schemes. He kept notes, scrawled into a battered notebook that lived in his jacket pocket.

Patterns emerged. Little ones, at first.

Certain tanks, with the exact same radios and antennas, just seemed to talk better than others.

Same set. Same model. Same nominal installation. Different results.

The official word from the Signal evaluation teams was that these variations came down to “random factors”—component tolerances, crew discipline, operator skill.

“Static,” Jimmy muttered whenever he read those reports. The word was becoming his own private curse.

He wasn’t convinced. The differences he was seeing were too consistent, too tied to certain hulls, certain antenna placements.

So he measured more.

He paced off distances in the dust between tanks, stopwatch ticking as he tested signal strength under different engine loads. He sketched out antenna positions. He noted which tanks seemed to get “lucky” in battle—crews reporting clear comms when everyone else heard nothing but white noise.

And then, one night in late October, hunched over a makeshift bench in a canvas tent with a kerosene lantern throwing long shadows, he saw it.

The tanks with better comms all shared something.

Their antennas weren’t exactly where the manuals said they should be.

A bracket bent during shipping. A field modification where some motor pool sergeant had shifted the mast three inches along the hull to keep it from catching on something. A “temporary” fix where a grounding strap had been reattached in a new spot.

Tiny changes, all of them. Random, accidental, or born of necessity.

But when he mapped them, the pattern was as clear as a baseball diamond. The antennas on those “lucky” tanks sat in positions where the conductive path between the mast and the hull traced out a very specific length. The geometry made the steel body of the tank resonate at the radios’ operating frequency.

The tank wasn’t blocking the signal. It was part of the antenna.

Jimmy sat back, heart pounding, mind sketching invisible electric fields across the canvas walls.

He flipped through his notebook, checking his assumptions. He’d never finished that engineering program, but he’d picked up enough antenna theory from ham radio manuals and Signal Corps lectures to know what a quarter-wave looked like when he saw one.

“Hell,” he whispered to the empty tent. “You magnificent hunk of metal. We’ve been fighting you instead of using you.”

If he could standardize that relationship between mast and hull—if he could rig a mounting bracket and tie-in wire that turned every M3 and M4 into a tuned radiating system—he could give every tank in the battalion the good luck some of them stumbled into by accident.

He filled page after page that night. Angles. Lengths. Diagrams. Calculations done half from memory, half from instinct. It wasn’t pretty math. But it was enough.

By dawn, he had a plan.

By regulation, that should have been the end of it.

He should have typed up a formal proposal, sent it up through channels, watched it disappear into the same black hole that had swallowed a hundred other field ideas.

Problem: Tank radio performance marginal. Solution: Modify antennas so hull acts as resonant structure.

The file would sit on a desk somewhere in New Jersey until the war ended, at which point a bored major might read it and sigh.

Instead, he grabbed his tools.

The first tank he modified was an old M3 that had seen better days.

The crew called it Jenny. It sat on the edge of the repair area like a sulking cow, tracks half off, engine stripped down. It wasn’t due back to the line for at least a week.

Perfect.

Under the grilling sun, Jimmy removed the standard antenna base from the rear of the turret and bolted his modified bracket in its place. He added a length of copper wire—the “spaghetti,” he joked to himself—running it from the mast connection down along the turret, across a weld seam, and into a point on the hull he’d selected with the care of a man defusing a bomb.

From a distance, it looked ridiculous. Copper against olive drab. A field-expedient clothesline.

Up close, it was beautiful.

He double-checked every connection, wiped sweat out of his eyes, and dropped into the cramped interior to hook the set back up.

“Jenny, you better make me proud,” he muttered, flipping switches.

He tuned the radio to a test frequency, keyed the mic, and called to Corporal Henley, who waited in a jeep a mile away with a portable set.

“Hen, you read me?” Jimmy asked.

“Loud and clear, Sarge,” came the answer, strong in his headset. “You’re booming. You sure you’re only a mile out?”

“Back it up another mile,” Jimmy said.

They did. Two miles. Three. Four.

Each time, the signal came back strong and clean—even when he revved the engine, even when he kicked on every electrical component he could.

He sat there in Jenny’s hull, grinning like an idiot, listening to Henley swear marvelously over the air at how clear everything sounded.

The standard install struggled beyond a mile under battle conditions. With this stupid-looking tangle of wire, he was pushing four without even trying.

It worked.

It really, actually worked.

And he wasn’t allowed to do it.

He went to his immediate superior anyway.

Captain Rodman was a by-the-book Signal Corps officer with spectacles that slid down his nose when he read technical bulletins and a nervous habit of straightening maps on the wall. He listened to Jimmy’s excited explanation with a deepening frown.

“You’re telling me,” Rodman said finally, “that you’ve modified an approved antenna installation in the field.”

“Yes, sir,” Jimmy said. “But—”

“Without a directive from the board. Without a test plan. Without authorization.”

“Yes, sir,” Jimmy said again. “But it works. I’ve got range reports, and—”

“The engineers at Fort Monmouth have been studying this problem for years,” Rodman cut in. “They’ve written entire volumes on why the hull interference problem can’t be solved without entirely redesigning the set or the tank chassis.”

“With respect, sir,” Jimmy said carefully, “I don’t think they’ve studied this.”

“In any case, that’s above your pay grade,” Rodman said. “You are not to modify standardized equipment without explicit approval. That’s not a request, Sergeant. That’s a direct order.”

Jimmy hesitated. “But sir, if we went to battalion with a demonstration—”

Rodman’s eyes hardened. “I said no. Restore the set to standard configuration and submit a report to me outlining your… findings. I’ll forward it through channels if it meets requirements.”

Jimmy knew what that meant. He’d seen it happen to other sergeants with clever ideas. The report would get attached to an existing file, stamped RECEIVED, and slowly buried under newer papers. Maybe some bored researcher would read it in 1947.

Meanwhile, tanks would keep dying in the present tense.

Jimmy left Rodman’s tent with a knot in his gut and his modified bracket still warm from the desert sun.

He put the bracket on Porkchop that night.

He told himself he was just testing. He told himself he’d take it off after the offensive, before anyone asked questions.

He knew he was lying to himself.

Porkchop’s commander, Lieutenant Harlan, watched with wary curiosity as Jimmy worked.

“That’s not standard issue,” Harlan observed.

“No, sir,” Jimmy said. “It’s an unofficial improvement.”

“You saying the people who built this pile of bolts got something wrong?” Harlan asked. There was humor in his voice, but his eyes were serious.

“I’m saying I’ve seen enough of our tanks go quiet at the worst possible moments,” Jimmy said. “And I think I know one reason why.”

Harlan studied him for a moment. He was young for a lieutenant, somewhere in his mid-twenties, with a Kansas drawl and a habit of spinning his class ring around his finger when he thought.

“What’s the worst that happens if your doodad doesn’t work?” he asked.

“Same as now,” Jimmy said. “Radio craps out in the middle of a firestorm. You hit the deck and pray.”

“And the worst that happens if some colonel sees it?” Harlan asked.

“I get my hide nailed to a board,” Jimmy said. “Might take your crew with me, too.”

Harlan considered that. The wind tugged at the tent flaps. Somewhere nearby, someone laughed too loud at a joke that probably wasn’t funny.

“You believe in this that much?” Harlan asked.

Jimmy met his eyes. “Yes, sir. I do.”

Harlan nodded once. “Then put it on. If some brass hat throws a fit, I’ll tell him I ordered it. Seems like a fair trade if it keeps my boys alive.”

By the time the artillery barrage began in earnest, Porkchop carried an extra length of copper wire, humming quietly against the turret as the tank idled in line with its brothers.

The British guns opened up at 2100—one thousand artillery pieces vomiting fire into the dark, the horizon pulsing like a thunderstorm frozen and played back on jittery film.

Jimmy watched the barrage from a shallow scrape beside the tank park, dust shivering on his boots every time the earth rolled under him. Even at this distance, the concussion thudded in his chest.

“Like the Fourth of July and the end of the world had a baby,” Henley muttered nearby.

Columns of armor began to rumble forward, silhouettes advancing in staggered lines toward the boiling wall of dust and smoke. Somewhere out there, the Afrika Korps was dug in behind minefields and anti-tank guns, waiting.

Harlan leaned out of Porkchop’s turret. “Grant! You sure about this thing?”

“No, sir,” Jimmy said honesty. “But I’m sure about what happens without it.”

Harlan nodded. He ducked back inside, disappeared behind the hatch.

Porkchop lurched forward with the rest, tracks grinding, engine roaring.

Jimmy jogged after them a few yards, as if sheer willpower could push the signal along that copper wire.

Then he stopped. This was as far as he went. The battle belonged to the men in the tanks now.

He made his way back to the communications tent. Inside, a wall map bristled with pins. Radios hummed. A harried lieutenant with headphones on both ears tried to juggle a dozen voices at once.

“Any word from Harlan’s platoon?” Jimmy asked Henley, who was manning one of the rear-area sets.

Henley put a finger up, listening. The speaker crackled, hissed, resolved into a voice.

“—this is Porkchop, Porkchop to Red One, we’re—”

Loud. Clear. Coming in like it was across a cornfield instead of through miles of exploding desert.

Henley’s eyebrows shot up. “Hear that?”

“Say again, Porkchop?” the battalion net controller asked, startled.

“We’re on the left of the British column,” Harlan’s voice came back, unhurried despite the distant thunder. “Taking some shell bursts, but formation intact. Red Two and Red Three in sight. Visibility low. Requesting correction on axis of advance, over.”

Jimmy’s heart hammered. He leaned in.

The controller rattled off bearings. Harlan confirmed. Other tanks chimed in. Red Two. Red Three. Red Four.

Jimmy listened for static and heard structure instead.

Commands went out. A warning about a suspected minefield. A call to shift a section ten degrees left to avoid a British unit drifting slightly off its line. A report from one lieutenant about enemy flares.

No screaming. No panicked “Say again?” Nothing like the chaos he’d gotten used to.

“Holy hell,” Henley whispered. “They’re… talking.”

A burst of interference cut across the net as a particularly big artillery salvo crashed down, but Harlan’s reply sliced through it a heartbeat later, clear as a bell.

“Copy, we see the flares. Adjusting. Tell those Brits to get their heads down when we pass them, this dust is murder.”

Behind them, in the command post, someone let out a disbelieving laugh.

Another tank commander’s voice broke in—one from a different company. “Who the hell is Porkchop and how come he’s the only one I can hear?”

Jimmy’s throat tightened.

It wasn’t perfect. Far forward, beyond the reach of his little experiment, the familiar, maddening pattern was playing out. Reports coming in half-heard. Entire platoons falling silent. Friendly units stumbling into each other’s paths unaware.

The night still chewed up men and machines with casual cruelty.

But somewhere in that chaos, one platoon of American tanks moved like they were connected, each one seeing what the others saw, hearing what the others heard.

And the difference, Jimmy knew, was a stupid-looking piece of copper wire.

Word spread faster than any formal memo ever could.

Within days, tankers were making excuses to drive by the maintenance area, peering at Porkchop’s turret like it was a shrine.

“You the guy who made Harlan’s radio not suck?” one gunner asked Jimmy, half-joking, half deadly serious.

“Depends who’s asking,” Jimmy said, looking over his shoulder toward Rodman’s tent.

“Name’s Collins,” the gunner said. “Before that offensive, I could barely hear my own platoon leader unless he was parked on top of me. Harlan was calling elevations like he was standing in my turret. Whatever you did, Sarge… that’s the difference between going home and being a greasy spot out there.”

Jimmy swallowed. Compliments like that didn’t feel like compliments. They felt like obligation.

“I just played with the antenna,” he said. “Don’t make it more than it is.”

“More than it is?” Collins snorted. “You just made forty-ton tanks talk like telephone operators. You got any more of those ‘plays’ in that notebook of yours, you let me know. I’ll sign up.”

He wasn’t the only one.

A lieutenant from another company approached Jimmy later, voice low. “I heard what you did on Porkchop,” he said. “Heard you broke a few rules.”

“Rumors travel fast in the desert, sir,” Jimmy said.

The lieutenant smiled thinly. “So does fire. I’ve got four tanks in my platoon that might not see Christmas if we can’t keep them coordinated. You want guinea pigs, you’ve got them.”

Jimmy hesitated. He could still hear Rodman’s order in his head.

Restore the set to standard configuration. Submit a report.

Instead, he’d done the opposite. He’d modified more. And now officers—officers—were asking him to break the same regulations on their machines.

“Why?” he asked. “You realize if this goes sideways, you’ll be in the sling with me.”

The lieutenant’s gaze went distant for a moment, out toward the blue line of the horizon where the desert bled up into the sky.

“I’ve got a kid brother who wants to be a pilot,” he said. “Told him I’d buy him a Chevy when I got home and he got his wings. Hard to do that if I’m buried under a sand dune in Tunisia because my radios sound like frying bacon.”

He looked back, eyes flat. “The Germans aren’t waiting for our paperwork. If that copper trick of yours gives us even a ten percent better chance of getting out of this alive, I’ll sign whatever confession they shove in front of me afterward.”

Jimmy looked at the antenna bracket in his hand.

“Okay,” he said. “But we’re doing it my way. I get to measure every hull, I get to tune every length of wire, and if some colonel comes down here breathing fire, you never heard of me. Deal?”

“Deal,” the lieutenant said, and spat into his palm, holding it out.

Jimmy hesitated a half-second, then clasped it, copper grease on his fingers.

Within a month, a quiet, unauthorized revolution had spread through the American armored park.

It moved not through memos, but through whispers. A tanker in one company would hear another company’s commander over the net clear as day and come prowling around the maintenance area with casual questions, like, “Say, you ever notice how some tanks just… talk better?”

Jimmy and a handful of sympathetic NCOs worked nights, installing modified brackets and wires, disguising them as best they could under canvas and clever paint jobs. They measured. They tested. They iterated.

He kept meticulous notes. Range increases. Clarity under engine load. Signal reliability during maneuvers.

The numbers didn’t lie.

Their tanks could now communicate clearly at three, four, even five miles under combat-like noise. What had been a lucky exception was becoming the new normal—for those in on the trick.

It was inevitable that somebody in authority would notice.

It was just a question of who, and when.

The hammer fell in February 1943.

The war had rolled on—through more desert battles, through the wrenching push into Tunisia. Tanks burned. Men died. Jimmy worked, slept little, and occasionally remembered there was a world somewhere beyond sand and static.

One morning, after a long night of chasing a ground fault in a command half-track, he was summoned to a tent he’d never been inside before.

Inside, the air was cooler. Cleaner. The table in the center was covered in neatly arranged papers, which was the first sign of trouble.

Three officers sat behind it.

Captain Rodman, face tight. A lieutenant colonel from the battalion staff. And a full bird colonel with the kind of clean, studied polish that screamed stateside, Ivy League, Signal Corps royalty.

The colonel wore perfectly pressed khaki and a pair of pince-nez glasses that made Jimmy think of bank managers and professors.

“Staff Sergeant James N. Grant,” the colonel read from a folder. “Signal Corps. Fifth Armored Battalion. Born Lima, Ohio. Civilian employment: radio technician. No formal engineering degree.”

Jimmy stood at attention, sweat prickling under his collar. “Yes, sir.”

The colonel closed the folder with a crisp snap.

“You’ve been modifying antennas on armored vehicles without authorization,” he said. No preamble, no small talk.

“Yes, sir,” Jimmy said. Lying would only make it worse.

“Do you have any idea how serious that is?” the colonel asked. His voice was calm, but there was a tightness around his mouth. “Standardization exists for a reason, Sergeant. We cannot have every mechanic with a soldering iron deciding he knows better than the design boards.”

“Sir, with respect—”

“With respect,” the colonel cut in, “you are out of line. The interference issues in armored radios have been thoroughly studied. The conclusions are clear. Any significant improvement is impossible without fundamental redesign of chassis and sets.”

He tapped the folder. “I have copies of those reports right here. Written by men with doctorates. Men who understand the physics involved.”

Jimmy’s jaw clenched. The words tasted like dust.

“I’ve read some of those reports, sir,” he said carefully. “They make a lot of sense on paper. But out here, in the desert, with these tanks…” He shrugged. “The paper’s not what’s bleeding.”

Rodman flinched. The lieutenant colonel looked like he wanted to be anywhere else.

The colonel’s eyes narrowed. “You don’t get to override certified findings because you don’t like the outcomes, Sergeant. You have violated technical regulations. You have risked damage to critical equipment. Your actions could have compromised operations.”

Jimmy bit back the urge to say, the operations were already compromised every damn time our radios went dead. Instead, he reached into his breast pocket, pulled out his battered notebook, and set it on the table.

“What’s this?” the colonel asked.

“My data, sir,” Jimmy said. “Range tests. Signal clarity reports. Engagement outcomes before and after modification. Testimonials from tank commanders. You want to crucify me, I understand. But before you do, you should at least look at what you’re crucifying.”

There was a long silence.

The lieutenant colonel looked down at the notebook, then up at the colonel. “Sir, I’ve… heard some of the same reports,” he said quietly. “From field officers. They say certain tanks are—well, performing better. Communications-wise. It… tracks with what Sergeant Grant claims he’s doing.”

“That’s anecdotal,” the colonel said briskly. “We don’t run a war on anecdotes.”

The tent flap rustled.

A fourth man stepped inside.

Conversation died like someone had flipped a switch.

Even without insignia, Jimmy would have known he was a general. Something in the way everyone in the tent suddenly straightened another quarter-inch, in the way the air pressure seemed to change.

The two stars on his shoulders confirm it. Major General Thomas Hightower, commanding armored formations across this chunk of North Africa. Jimmy had seen him once from a distance, standing on a jeep, talking to tank crews with his sleeves rolled up and his hat pushed back.

Now he was here, in the tent, eyeing the table with lazy curiosity.

“At ease,” Hightower said. He nodded at the colonel. “Heard there was a party. Thought I’d drop by.”

“General Hightower,” the colonel said, half-standing. “We’re conducting a technical review regarding unauthorized modifications to radio equipment.”

“So I’ve been told,” Hightower said. He walked closer, picked up Jimmy’s notebook without asking, flipped through it with an unreadable expression.

“Sergeant Grant, is it?” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“You’re the one who’s been turning my tanks into radio stations.”

“Trying to keep them from becoming tombstones, sir,” Jimmy said, before he could stop himself.

Rodman made a tiny strangled sound. The colonel inhaled sharply.

Hightower’s mouth twitched, just enough to suggest amusement.

“Colonel?” he asked, not looking away from the notebook. “You’ve heard his idea.”

“Yes, sir,” the colonel said. “It’s… unorthodox. And contrary to established doctrine. The physics—”

“Does it work?” Hightower asked.

“Sir, the theoretical underpinnings—”

“I didn’t ask about the theory,” Hightower said. He looked up, eyes sharp. “I asked if it works.”

The colonel floundered for a moment. “I—have not personally examined the equipment.”

“I have, sir,” Rodman said suddenly, surprising himself. His face was pale, but his voice was steady. “I mean… I’ve been in the same command tent while modified tanks were on net. The comms are… markedly clearer. Field officers are reporting better coordination.”

The colonel shot him a betrayed look.

Hightower turned to the lieutenant colonel. “You?”

“Same, sir,” the lieutenant colonel said. “The battalion that has the most of these… modifications… has seen fewer blue-on-blue incidents. Better maneuver control.”

Hightower nodded thoughtfully. He turned back to Jimmy.

“Sergeant Grant,” he said. “In one sentence, what did you do?”

Jimmy swallowed. “I made the tank part of the antenna, sir.”

“And what do your numbers tell you?” Hightower asked. “Not your hunch. Your numbers.”

“Range improved three to four times under combat-like conditions,” Jimmy said. “Signal clarity holds even with engine at full load. We can talk to tanks four miles out like they’re parked in the motor pool.”

Hightower let that sink in.

Then he set the notebook down and looked at the colonel.

“If my sergeant has found a way to make my tanks talk to each other through the noise,” he said, “I don’t give a damn if it offends every professor in New England. We’re not grading him on elegance. We’re counting the boys who get to go home.”

“Sir, the regulations—” the colonel began.

“Will be updated,” Hightower said. “By you. To reflect the change. In the meantime, I want this… stupid antenna trick”—he smiled faintly at his own phrase—“installed on every tank in my command that can roll under its own power.”

He leaned across the table, close enough that Jimmy could smell coffee and cigarette smoke.

“You up for that, Staff Sergeant?” Hightower asked.

Jimmy’s throat felt tight. “Yes, sir.”

“Good.” Hightower straightened. “Colonel, you can write your memos. I’ll write my after-action reports. Let’s see which has more influence on the outcome of this war.”

They started with forty tanks.

Forty hulking M3s and M4s rolled out to a stretch of open desert that doubled as a training ground. Armored crews grumbled about the heat, the dust, the fact that the promised mail from home hadn’t arrived yet.

Jimmy and his newly promoted team—he’d made tech sergeant last week; the ink was barely dry—worked down the line, installing brackets, running copper wire, bolting down connections. They’d refined the design by now: less spaghetti, more clean angles, snug fittings that looked almost official.

Almost.

Hightower insisted on being there for the tests. So did half a dozen staff officers, some skeptical, some curious.

“Looks like you decorated my tanks with jewelry, Sergeant,” Hightower remarked, shading his eyes against the sun.

“Ugly jewelry, sir,” Jimmy said. “But functional.”

They set up a series of test stations at increasing distances: one mile, two, four, eight. Trucks with portable sets. Jeeps with whip antennas. Static-filled world war turned into a laboratory, just for an afternoon.

Then they started rolling.

Forty tanks spread out across the sand in two wedges, dust plumes rising behind them. The ground shook as they picked up speed. Inside, commanders wore headsets, loader’s faces smeared with grease, gunners squinting at optical sights just for the feel of it.

“Red One to all Red elements, radio check,” came the first call. “Report in, over.”

Responses came in like a zipper: Red Two, Red Three, Red Four, all the way up to units from other companies, their call signs overlapping but clear.

“Range test, four miles,” called the controller in the main tent. “Modify your axis, execute turn forty-five degrees right on my mark. Acknowledge.”

Every tanker heard. Every tanker acknowledged.

From the observation post, Jimmy watched forty steel beasts pivot in near unison, like a flock of monstrous birds banking as one.

Dust swirled. Engines roared. Radios crackled—but with language, not noise.

“Holy—” Henley began, then caught himself, mindful of the general a few feet away.

Hightower’s binoculars stayed glued to his eyes. “I’ve seen dance lines less coordinated than this,” he muttered.

At eight miles, with the tanks reduced to insects on the sand, the controllers could still reach them. Commands went out. Observers annotated responses. Staff officers scribbled note after note, their skepticism eroding under a tide of data.

The colonel from the board was there, too, lips pressed thin. Jimmy caught him once, staring at a readout, shaking his head in grudging amazement.

Afterward, back in the shade of the big tent, while the tank crews refueled and swapped exaggerated stories about who had come closest to running over a camel, Hightower clapped Jimmy on the shoulder so hard his teeth clicked.

“Sergeant,” Hightower said, “that was the prettiest thing I’ve seen since my wife walked down the aisle.”

“Just wires and metal, sir,” Jimmy said, dazed.

“Yeah,” Hightower said. “Just wires and metal, and a hundred men who might live long enough to tell their grandkids about this stupid war. We’ll get you more wire. You get me more tanks like that.”

He turned to his staff. “Send a message to theater command,” he said. “Effective immediately, Grant’s antenna modification is authorized for all armored units. I want implementation orders on every bulletin board from here to Oran.”

The colonel cleared his throat. “We’ll need an official designation, sir,” he said.

Hightower grinned. “Call it… Antenna Modification Pattern Number Seven. Sounds fancy enough. But the boys will call it what they like.”

He looked back at Jimmy.

“They’ll call it the Grant,” he said. “Whether you like it or not.”

Jimmy didn’t like it.

He loved it. And he was terrified by it.

Because now, if anything went wrong, it wouldn’t just be his secret anymore.

It would be his responsibility.

Tunisia, May 1943

The end of the North African campaign came not as a neat, cinematic finale, but as a series of hard, dusty pushes that eroded the German lines until they cracked.

The Americans had learned fast from their bloody nose at Kasserine. They’d changed commanders, tactics, even attitudes. They’d stopped underestimating the man with the Afrika Korps badge.

And now, they had something else the Germans didn’t know about yet.

On a cool morning in early May, a squadron of Shermans from the 4th Armored Regiment—each one carrying the Grant-modified antenna setup—rolled out toward a set of low hills near Tunis. The objective was a German defensive position anchored on an anti-tank gun line and backed by Panzer IIIs.

Sergeant William “Billy” Peters, tank commander of Sugar 12, had been skeptical when they’d first bolted Jimmy’s copper contraption to his turret weeks before.

“What’s this, decoration?” he’d asked back then, eyebrows up.

“Just a stupid antenna trick,” Jimmy had said. “Humor me.”

Peters, like most long-service NCOs, had a finely tuned sense for bullshit. He’d sniffed at the wire, then shrugged.

“If it keeps my boys from dying because some knucklehead can’t hear me, you can hang Christmas lights on this thing too,” he’d said.

A week later, in a minor scrap, he’d heard a flanking tank’s panicked warning about an 88 in time to back his own vehicle out of what would have been a fatal line of fire.

He became a believer after that.

Now, as Sugar 12 led its platoon toward the hills, Peters’ voice filled the net with steady commands.

“All Sugar elements, this is One-Two,” he said, words flowing calm despite the tension. “Maintain staggered line. Watch your interval. We’re gonna tickle those Jerries in front, then wrap ‘em up like a Sunday roast.”

The plan was textbook double envelopment. Fix the enemy with frontal fire, send two elements around the flanks, squeeze.

Textbook plans were easy to write and hard to execute, especially when you couldn’t talk.

Today, they could talk.

“Sugar 13, you’re drifting,” Peters called. “Slide left, keep that spacing, you’re gonna get cozy with a minefield otherwise.”

“Roger, One-Two,” came back the reply, immediate and crisp.

“Sugar 14, suppress that ridge line on my mark. Sugar 15, get ready to peel off right when I say go. Stick your nose out too far, you’re gonna lose it. Copy?”

A chorus of acknowledgments rolled back. Peters could practically picture each commander’s face.

The first German shots came from the crest of the opposing slope—cracks and flashes, shells plowing up sand in front of the advancing Shermans. An 88 roared somewhere to the left.

“Contact front, two o’clock, estimated eight hundred,” called Sugar 14. “See muzzle flashes. Engaging.”

“Sugar 15, smoke that left side,” Peters ordered. “I want those 88 eyes watering.”

White smoke blossomed, drifting over the base of the ridge. The Shermans’ 75s barked, sending high explosive shells slamming into the German positions.

Under ordinary circumstances, this was the point where things started to fall apart.

Noise. Dust. Confusion. A tank hit, swinging sideways. Somebody misreading a hand signal. A radio transmission lost under engine roar.

Not today.

“Sugar 11 just took a hit, we’re buttoned up but mobile,” came a voice on the net. “No penetration. Shook the fillings out of my teeth though.”

“I feel for you, Eleven,” Peters said. “Hold steady. Fourteen, keep their heads down. Fifteen, with me. We’re going right. Thirteen, you go left on my mark. On three. One… two… three. Move.”

Sugar 12 and 15 broke right, engines surging. Sugar 13 swung left. The German anti-tank gunners, focused on the Shermans to their front, tried to traverse, but every time a head popped up to adjust a sight, a shell from 14 reminded him of the danger.

“Panzer threes coming up from the rear!” someone shouted as dust plumes appeared behind the German line. “Three of ‘em, trying to plug our right!”

“I see ‘em,” Peters said, heart pounding. The Panzers slid between patches of smoke, angling to intercept his envelopment.

Under the old comms, maybe one or two tanks would have seen that move coming. Maybe the warning would’ve arrived garbled, or too late. Today, everyone on the net knew within seconds.

“Sugar 15, keep your nose pointed at those Panzers,” Peters snapped. “Fourteen, put HE on their flank if you can. Thirteen, don’t you dare stop that left hook, those guns up front still need loving attention.”

They fought like that—not as isolated islands, but as a chain of minds in steel bodies, each aware of the others’ intentions. When one tank hit a mine and lurched to a stop, the driver of the following tank heard the warning as soon as it left his buddy’s mouth and swung wide instead of plowing into the same trap.

Seventeen minutes later, the German position was in ruins.

The Panzer IIIs lay crippled, tracks blown, turrets twisted. The 88s were silent, gun shields shredded.

The Shermans of Peters’ squadron sat in a loose horseshoe around the smoking wreckage.

Only one American tank had been disabled. The crew climbed out, shaken but alive.

“Kill count?” someone asked over the net, shaky laughter in his tone.

“Twelve of them,” Peters said, voice quiet. “None of us. I’ll take that trade every day and twice on Sunday.”

Back at battalion, the after-action reports recorded the cold numbers: 12 enemy armor destroyed. One friendly tank disabled. No KIA.

But in the mess tents, in the smoke breaks behind supply trucks, the story spread with a different emphasis.

We moved like one machine, they said. We knew where everyone was. We heard everything. We weren’t guessing. We were fighting.

And always, somewhere in the retelling: because of Grant’s stupid antenna trick.

The war rolled on, its theater changing from sand to scrub to mud.

Sicily. Italy. Hill towns and vineyards scarred by shells.

By July 1943, the Grant modification—Antenna Modification Pattern No. 7, in the official dull language—had spread beyond Jimmy’s immediate command. Technical bulletins from theater headquarters described the field procedure in dry detail. “Field units are authorized and encouraged to retrofit existing armored vehicles…”

American armored units arriving in Sicily found their tanks already equipped with the copper jewelry, factory-installed thanks to revised production specs. Crews treated it as just another part of the machine, like a periscope or a hatch hinge.

They didn’t know, couldn’t know, what it had been like without it.

Jimmy went where the tanks went. His MOS didn’t care much which patch of ground they were currently burning up. He rode transports from North Africa to Sicily, from Sicily to the Italian mainland. Between deployments, he trained other techs in the modification, teaching them how to see the hull not as an obstacle, but as part of the antenna.

He grew tired. Older. His hair thinned at the temples. His hands, once only calloused from wire and solder, developed the permanent tremor of a man who’d had to write too many condolence letters in his head.

He never got comfortable with the praise.

An aide to some general in Naples cornered him once, asked if he wanted to come to a ceremony. There was talk of medals, citations, recognition for “outstanding technical innovation under combat conditions.” His name had been bandied about in certain circles.

Jimmy shook his head.

“Give it to the crews who first let me bolt that mess to their turrets,” he said. “They’re the ones who took it into fire.”

“You don’t want your name in the paper?” the aide asked, incredulous.

“I didn’t do it for the paper,” Jimmy said.

He did write one long letter—to his mom back in Ohio, explaining as best he could what he’d done.

She wrote back saying she’d tell the ladies at church to pray for his hands, since his head sounded like it was already in the right place.

War ended the way big things often do: not with a single final bang, but with a gradual realization that the bangs had stopped meaning the same thing.

In Europe, cities burned and surrendered. In the Pacific, islands were taken at horrific cost, then the unthinkable happened over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Jimmy watched some of it from repair depots, some of it from the backs of trucks, some from the flickering newsreels when he could steal an evening at a base theater.

He took his discharge in late 1945.

The Army offered him a commission if he wanted to stay—Signal Corps, research work, maybe even a slot at a university. The letterhead was very impressive. The language was flattering.

He pictured himself in a lab back in the States, wearing a tie, standing in front of a chalkboard full of equations. The idea made his skin crawl.

“Appreciate it,” he told the personnel officer. “But I think I’ve argued with enough radios for one lifetime.”

He took a train back to Ohio. The country rolled past his window—fields, towns, factories switching back to products that weren’t designed to kill anyone. Everywhere, men in uniforms got off and came back without them, turning into civilians again as if peeling off a skin.

His hometown had changed less than he had.

The same Main Street. The same diner. The radio shop where he’d once worked had a new owner, but the sign was the same.

He got a job at a different shop in a bigger city—Cleveland, then later Chicago—fixing televisions and radios for people who’d use them to watch baseball and sitcoms instead of war news.

He married once, briefly. It didn’t stick. The war had given him more patience for wires than for arguments.

He never told anyone in his building what he’d done overseas. As far as they knew, he was just a quiet vet who could make a dead set sing again.

He liked it that way.

In some dusty file cabinets in Washington, the name Grant appeared in technical summaries as part of a list of contributors to wartime communications improvements. Engineers after the war read about “integrated hull antenna systems” and “field-driven modifications in armored radio performance,” and built on them.

New generations of armored vehicles—Pattons, then Abrams—rolled out of factories with sleek, hidden antenna systems that owed their lineage to a stupid-looking tangle of copper in a North African tent.

The people who designed those modern systems had degrees on their walls.

Somewhere in the footnotes, there was probably a reference if you looked hard enough: Grant, J. N., field report, 1943.

History, in the capital-H sense, moved on.

Jimmy fixed radios.

In 1978, in a small town in upstate New York where Jimmy had moved to be closer to a niece and her kids, his phone rang on a Tuesday afternoon.

He’d been halfway through rewiring the tuner on an old tube set. He wiped his hands, picked up.

“Grant Radio Repair,” he said.

There was a pause. Then a man’s voice, old now, roughened by years and cigarettes, came on the line.

“Sergeant Grant?” the man asked. “James N. Grant?”

“Just Jimmy these days,” he said. “Who’s this?”

“Name’s Fred Collins,” the man said. “You probably don’t remember me. I was a gunner in one of the Shermans back in ‘43. Fifth Armored.” He hesitated. “I’ve been trying to track you down for ten years.”

Jimmy leaned against the counter, the phone suddenly heavy in his hand.

“Collins,” he said slowly. “You had the tank with the pinup painted on the side. What’d you call her? Daisy?”

Collins laughed, the sound unexpectedly bright. “Damn. You do remember.”

“I remember you came into my tent and told me if my ‘copper spaghetti’ screwed up your radio, you’d personally make me eat it,” Jimmy said.

“Yeah,” Collins said. “Never more glad to be wrong in my life.”

Silence hummed between them for a moment, full of memories neither of them had asked for.

“What can I do for you, Fred?” Jimmy asked.

“I just… had to tell you something,” Collins said. His voice thickened. “I read this article in some military history magazine last year. They were talking about antenna systems on tanks, this ‘Grant modification’ they called it. They made it sound like some abstract technical thing. No names. Just… concepts.”

He took a breath.

“I remembered you,” he said. “I remembered what it was like before and after. Before, going into a fight felt like being shoved into a dark room with a hundred guys and told not to bump into each other. After, it was like someone turned on a damn light.”

His voice shook.

“We came home because of that, Jimmy,” he said. “Me. My driver. My loader. The guy who took over my old seat when I swapped tanks. We got to meet our kids, grandkids, because when you yelled at physics, physics blinked.”

Jimmy swallowed hard. His eyes stung. He sat down heavily on a stool, the coil of wire on his workbench blurring.

“I didn’t—” he started, then stopped. “I mean, it wasn’t just me. It was crews who trusted something that looked like it came off a bad ham radio project. Generals willing to piss off their own engineers. A hundred little things.”

“I know,” Collins said. “But I needed to say thank you to the man who started the stupid ball rolling.”

Jimmy let out a breath that sounded almost like a laugh.

“You could’ve just sent a postcard,” he said, to cover the emotion.

“Could’ve,” Collins said. “Didn’t feel like enough.”

There was another pause. Jimmy heard kids shouting in the background on Collins’s end, the muffled sound of a television game show.

“You ever think about it?” Collins asked quietly. “What you did?”

Jimmy looked around his little shop—the shelves lined with sets, the wall calendar stuck on last month because he didn’t care much about days. He looked at his hands, scarred with little burns, older now, but steady.

“Sometimes,” he admitted. “Usually when I hear about some new tank on the news and see those slick little antennas recessed into the armor. I figure they’re the great-great-grandkids of my copper spaghetti.”

“My grandson is joining the Army next year,” Collins said. “They’re probably gonna put him in a vehicle that talks like a telephone switchboard. I like to think part of that is you. Makes it easier to sleep, knowing we left something better behind than what we started with.”

Jimmy smiled, a small, private thing.

“I’ll drink to that,” he said.

“Hell, I already did,” Collins said. “Couple decades running.”

They talked a little longer. About nothing and everything. About arthritis and the price of gas, about where the boys they’d served with had ended up—those who had.

When they hung up, Jimmy sat for a while in the quiet shop.

Outside, cars rolled by on the street. The world buzzed with invisible waves—TV, FM radio, CB chatter, early cellular traffic. All of it reliant on antennas no one thought about unless they snapped off in a storm.

He picked up a scrap of wire from his bench, turned it between his fingers.

He thought of tanks in the desert, hulks silhouetted against artillery flashes. He thought of young men in steel cages, listening for a voice that meant survival.

He thought of a general asking him, Does it work?, and choosing to care more about outcomes than about who got credit.

He thought of the colonel with the degrees, who’d never apologized, but who, according to a rumor Jimmy had picked up once, had gone on to champion unconventional antenna research in the postwar years.

He thought of the word that had always bothered him: impossible.

A tank was supposed to be a Faraday cage. Something that ate radio waves. That was what the experts had said.

He’d taken that box and turned it into a whispering giant instead.

It hadn’t won the war by itself. Wars were never that simple. But in dusty places with names half his neighbors couldn’t pronounce, it had helped a few more men move like one, instead of dying one by one.

He set the wire down carefully.

Then he went back to work on the old TV set.

The picture snapped into focus five minutes later, resolving into a baseball game—outfield bright green, stadium lights glaring, announcer’s voice crisp.

The batter swung. The crowd roared.

Signals, Jimmy thought. Just signals.

Sometimes, if you listened close enough, and refused to believe the noise was all there was, you could find the pattern.

You could turn forty voices into one.

You could make machines move like a flock of birds instead of a herd of blind cattle.

You could take something everyone else insisted was a problem and make it part of the solution.

They’d laughed at his stupid antenna trick.

He smiled faintly at the memory, adjusted the horizontal hold on the TV, and decided he was okay with that.

They weren’t laughing now.

THE END

News

“Where’s the Mercedes we gave you?” my father asked. Before I could answer, my husband smiled and said, “Oh—my mom drives that now.” My father froze… and what he did next made me prouder than I’ve ever been.

If you’d told me a year ago that a conversation about a car in my parents’ driveway would rearrange…

I was nursing the twins when my husband said coldly, “Pack up—we’re moving to my mother’s. My brother gets your apartment. You’ll sleep in the storage room.” My hands shook with rage. Then the doorbell rang… and my husband went pale when he saw my two CEO brothers.

I was nursing the twins on the couch when my husband decided to break my life. The TV was…

I showed up to Christmas dinner on a cast, still limping from when my daughter-in-law had shoved me days earlier. My son just laughed and said, “She taught you a lesson—you had it coming.” Then the doorbell rang. I smiled, opened it, and said, “Come in, officer.”

My name is Sophia Reynolds, I’m sixty-eight, and last Christmas I walked into my own house with my foot in…

My family insisted I was “overreacting” to what they called a harmless joke. But as I lay completely still in the hospital bed, wrapped head-to-toe in gauze like a mummy, they hovered beside me with smug little grins. None of them realized the doctor had just guided them straight into a flawless trap…

If you’d asked me at sixteen what I thought “rock bottom” looked like, I would’ve said something melodramatic—like failing…

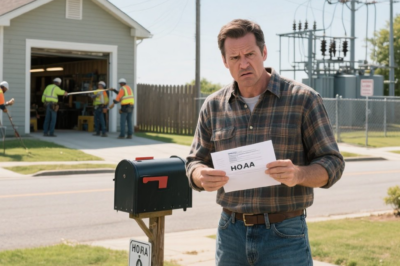

HOA Cut My Power Lines to ‘Enforce Rules’ — But I Own the Substation They Depend On

I remember the letter like it was yesterday. It came folded in thirds, tucked into a glossy HOA envelope that…

I Overheard My Family Planning To Embarrass Me At Christmas. That Night, My Mom Called, Upset: “Where Are You?” I Answered Calmly, “Did You Enjoy My Little Gift?”

I Overheard My Family Plan to Humiliate Me at Christmas—So I Sent Them a ‘Gift’ They’ll Never Forget I never…

End of content

No more pages to load