Mistress Attacked Pregnant Wife in the Hospital — But She Had No Idea Who Her Father Was

Part I — The Corridor

The sound came first, a braid of crying and shouted words that didn’t belong anywhere near an obstetrics ward. Wheelchairs paused. Nurses looked up as one. In the bright corridor, a woman in a royal blue dress had both hands knotted in the hair of a patient still in her hospital gown, eight months pregnant and bracing with one hand against the wall to keep from falling.

The patient’s name was Sienna Hol. She was twenty-eight, all edges sanded down by a lifetime of being told to keep the peace. Her other hand—knuckles white—held the ridge of her belly, her breath stuttering against a contraction that wasn’t supposed to be here yet.

“Let go,” Sienna managed, voice ragged.

“Let him go,” the woman in blue shot back, yanking. “You think you can keep him with a baby? Pathetic.”

Mara Steel had entered the hospital like she owned it—heels cracking against tile, perfume arriving ahead of her, rage arriving with her. There’d been whispers about her at charity events even before she started sleeping with Jordan Hol. She was beautiful in a way that made people throw adjectives at her and then forgive themselves later for not noticing the sharpness underneath. She was the wrong kind of brave.

A nurse lunged. Another called security. A third fumbled for the emergency button and missed it, hands shaking. The seconds stretched, elastic and useless.

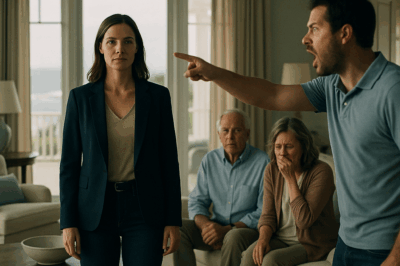

“Enough,” a man’s voice said, and the corridor obeyed.

He wasn’t young. Silver hair cut with a practical hand. Dark overcoat in a place where people kept their sweaters folded on chair backs. He didn’t look angry; he looked like a man so used to being obeyed that he rarely had to raise his voice. But there was an edge in it that made everyone in the hallway check their posture.

“Take your hands off her,” he said to Mara without looking at her.

“Who—” Mara started, then stopped when she saw the ripple of recognition travel down the hall like a breeze. The nurse at the desk stood up straighter. The hospital administrator, who’d arrived on the first buzz of trouble, dropped his eyes.

The man moved to Sienna and eased Mara’s hands away like undoing a knot. He put his palm against Sienna’s forearm, thumb rubbing once as if to say breathe. His gaze caught her face and held for a beat too long, something cracking and reassembling in the space behind his eyes.

“No one touches my family again,” he said. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to.

“My… what?” Mara scoffed, but softer. “Family? Her?” She took in the gown, the bare feet, the tears, and smiled a quick, cruel smile. “If this is your family, then I guess standards—”

An assistant had appeared beside the man, already on the phone. Outside, like weather, reporters began to gather. The hospital’s security team moved in with faces that said they would rather be anywhere else. A pair of officers—one with a pen already uncapped—took in the scene with a look that was not quite boredom and not quite dread.

Sienna swayed. The man caught her elbow. “I’m Arthur,” he said, softening as he turned back to her. “Arthur Vaughn.”

The name pulled a small gasp from the administrator. Even the cop’s pen hesitated. Vaughn: the kind of name that got things built or torn down, depending on how the day had gone. Shipping, real estate, a foundation with a tasteful, modern logo. The kind of name that lived on plaques and in editorials and above lobby doors.

The name meant nothing to Sienna. All she knew was that her scalp burned, her stomach ached, and the man saying calm down to the screaming woman had a voice she wanted to believe.

“Ma’am,” the officer said to Mara in a tone he had practiced, “you’re coming with us.”

“For what?” she demanded, but it came out breathless.

“Assault,” the officer said. “We’ll sort the rest downtown.” He glanced at Arthur and then away, embarrassed by the reflex.

Jordan arrived panting and late, expensive jacket thrown over a T-shirt as if he’d been interrupted on the way to being someone else. He looked at Sienna, then at Mara, then at Arthur, and picked the wrong person to address.

“Mara—” he started, hands out as if he could gather the pieces back and no one would notice they didn’t fit anymore.

Arthur didn’t look at him. “You’ll wait there,” he said, and pointed to the far wall. Jordan went, somehow, as if the air had moved around him and left only one path.

Arthur turned back to Sienna. “You’re safe now,” he said, and his voice dropped into a register that had nothing to do with money. “I’m here.”

“Who are you?” she asked, because fear says what it wants, not what is polite.

He was about to answer when her doctor sprinted down the hall. “We’re moving,” the doctor said, eyes darting from Sienna’s stomach to the chart to the machine’s stubborn numbers. “Now.”

Arthur brushed a piece of hair from Sienna’s forehead with a single practiced motion that should have belonged to someone who knew her. “I’ll be right here,” he said. “I promise.”

As they pushed her bed toward the double doors, Sienna closed her eyes against tears that were making everything too blurry to understand. The last thing she saw was Mara, cuffed, still trying to make the moment about herself. The last thing she heard was Arthur saying to someone on the phone in a voice so flat it could cut, “Call the lawyer. No statement. Protect the patient.”

When the doors swung shut, the corridor exhaled as one.

Part II — Before

Before the hospital hallway, before the polished floors and questions and the way promises could sound like lies, there had been a kitchen with a table that wobbled when you leaned on it. A girl named Sienna taught herself how to keep it steady by planting her palm hard on one corner and pretending the trick was magic. Her mother worked two jobs that added up to one life that didn’t.

“Where’s Dad?” she had asked when she was five and then again when she was nine and then again when she had already decided the answer.

“Gone,” her mother said. The word meant: a man who couldn’t handle responsibility, a man who took the car and the good towels and left behind the mortgage and a dent in the drywall where he had thrown his keys too hard the last time he came through the door. Her mother said he wasn’t worth mentioning. She said it often enough that Sienna learned to stop asking. She internalized the lesson the way you do at twelve: if someone leaves, the person left must learn to be very light so it won’t happen again.

She made straight lines out of messes. She apologized before she had to. She learned to love people where they were instead of where they should have been.

Jordan had seemed like a man who would keep her from breaking into too many pieces. He was funny. He had a quick mind and the kind of ambition that sounded like safety when it talked about the future. He told her he’d grown up poor too. They counted coins and jokes at a diner and left a big tip when his first promotion came through. They talked about babies in the abstract and dogs in the concrete and bought a plant they both forgot to water.

He started staying late. He put his phone face down on restaurant tables. He told her she was overreacting when she said she smelled someone else’s perfume on the collar of his coat. When she finally found the messages, it felt less like a betrayal and more like something falling into place, which was the worst part.

“I didn’t lie,” he said, meaning I didn’t volunteer information. “Mara understands me better.”

“Better than what?” she asked.

“Better than this,” he said, and gestured around the small living room, taking in the couch where they had fallen asleep watching a show dumb enough to forgive, the chipped mug she always used for tea, the photos that all had the same soft look because she hadn’t learned to take pictures when she wasn’t trying to make something look presentable.

He left with a duffel bag and righteous exhaustion. She leaned against the door and tried not to make a sound because sometimes quiet is the only dignity left available.

The pregnancy had been the good part, steady and simple until it wasn’t. The doctor said bed rest. The baby said dancing. The cramps said maybe today. Sienna checked into a private hospital because the brochure had said words like serene and calm. She didn’t tell anyone except the one friend who still texted, the one who asked if she should come sit in a chair and read magazines while Sienna slept, which sounded so lovely Sienna cried.

She didn’t tell Jordan. She didn’t tell Mara. She didn’t think of them as a they. That was her mistake.

Part III — The Room

The delivery room was too bright, which is appropriate and also ridiculous. Labor is holy and ugly and honest; it deserves candlelight and applause. Sienna’s doctor did not applaud. She did what you do: checked, asked, held, coached, repeated. She had the soft jawline of someone who takes good care of her irons and her opinions. She had learned to say you’re doing so well without making it sound like condescension.

Between contractions, Sienna thought about the man in the hall. Arthur. His voice had sounded like a hand she might hold if the room got very dark. But the voice in her head was her mother’s: no one is coming. You do this yourself.

“Breathe,” the nurse said, and Sienna discovered there are a hundred ways to do that wrong.

In the corridor, Arthur stood like a guard dog who had learned to use a phone. He made two calls in a language that was not English—the particular dialect of wealth that sounds like “we will not be issuing comment at this time” and “the hospital’s liability is clear” and “my daughter will not be in the same air as that woman again.”

Jordan tried to approach twice and got repelled twice. The second time, Arthur turned and pinned him with a look that had emptied boardrooms. “You are not ninety feet tall,” Arthur said. “You are not a parable. You are a middle manager with a mess on his hands. Stay away from my daughter.”

“Your—” Jordan started, and then shut his mouth so fast a tooth clicked. “She said her father—”

“She said what she was told to say,” Arthur said, and it was the first hint that the history here had edges.

The first cry cut through the ward like a siren, except lovely. Arthur closed his eyes for a second and pressed a hand against the wall. An old man in a gurney rolled by and patted his sleeve. “It’s all right,” the old man said, the way old men do to other men when they remember and don’t want to. “The world keeps turning.”

When Arthur stepped into the room, the world narrowed to a point. A nurse handed him a gown and Dr. Levine—name badge askew, hair escaped from tidy bun—nodded at him like she had decided not to resent the presence of money for once because it belonged to someone who looked very much like a father.

Sienna held the baby the way you hold something that used to be inside you and might go back if you blinked wrong. She looked up when she heard the door. For the first time since the corridor, she wasn’t crying.

Arthur didn’t know whether to approach. He lingered, hand on the knob. When she finally said, “Who are you?” it wasn’t distrust. It was logistics. He took a step, then another.

“I’m someone who should have never left,” he said. He had rehearsed a thousand honest sentences for a thousand imaginary doorways. None of them worked here. “I’m Arthur Vaughn.”

“Vaughn,” she said, as if tasting the word. “That’s… my father?”

“If you’ll let me be,” he said, and the humility in it surprised even him.

The baby hiccuped. The sound was a penny dropped down a well. Sienna cried again, but quietly, like a person dehydrated and grateful for water. He stood near the bed and did not reach for the baby because this moment was not his even a little. He looked at Sienna’s face and saw his own mother’s eyes looking back from another century. He had not believed in time travel until that second.

“Why now?” she whispered. “Why… here?” She glanced toward the door as if the corridor had become myth.

“Because a divorce attorney and a messy fight and a judge who made the wrong call and my own stupidity made me into a man my ex-wife could erase,” he said, the sentences tumbling into themselves with the energy of a confession that has waited too long. “I tried and failed and tried again and failed bigger. I looked for you. I hired people. I went to the house where you used to live and got told I had the wrong address. I… I don’t expect you to believe any of that.”

She looked down at the baby. She looked at the hand on the blanket, at the fingers uncurling and curling like seahorses learning to be hands. “I believe my son has a grandfather,” she said. “That’s enough for today.”

He exhaled a sound he had not allowed himself at a board table or a funeral or a hospital bed or in the back of a car waiting for a verdict. He did not cry. He did the older-man version: he laughed once, softly, like a pipe belching air, and then he smiled in a way that didn’t pull at his face.

Part IV — Names and Papers

The news cycle began before dawn. Even outlets that should have known better ran with the alt-text version of the story. Mistress Attacks Pregnant Wife in Hospital. Some added the garnish of celebrity: Daughter of Billionaire Arthur Vaughn Assaulted by CEO’s Mistress. Someone resurrected a photo of Mara from a gala, zoomed in so far that the pixels did the heavy lifting, and put it beside a screen grab of her in handcuffs like a before-and-after nobody wanted.

Arthur did not enjoy learning how fast reputations can be ruined. He had ruined a few himself and knew the math: speed multiplied by the satisfaction of being right about people you never liked. He had no sympathy for Mara. He had some for the city.

Lawyers appeared with printouts and pencils and ways of saying no that could be framed and hung in offices. Papers were drawn up, protective orders entered, hospital protocols updated so quickly it looked like they had been waiting in a drawer.

Jordan lost his job, which was inevitable once the statement went out that the company did not tolerate violence or those adjacent to it. He called. He texted. He sent an email that started with, We need to talk about custody and ended with, I didn’t hit you, as if proximity were absolution. He left a voicemail that started with, I’ve been thinking and ended with, if you love me you’ll—

Arthur changed Sienna’s number and installed passcode locks on the entryway of her apartment and then moved her out of the apartment because security theater has its place but reality prefers doors that fit their frames.

He offered her a house. She said no at first. She had been told all her life that accepting help was signing a contract in someone else’s ink. He didn’t push. He asked what would make her feel safe. She said: windows that lock, a doorbell camera, a fence the dog can’t squeeze under, a washer that doesn’t insist on walking across the kitchen when it spin-cycles. He said: done.

He had a way of saying done that wasn’t arrogant. It was efficient. It said: my money is a tool, let me use it.

She named the baby Miles, a name with music inside it. Arthur asked if he could take the 2 a.m. shift one night. He sat in a chair that was not designed for anyone older than thirty, watching a creature whose primary talent was making a sound like a squeaky shoe and turning purple when annoyed. He had never gotten to do this when his own child was new. He had been attending something—meetings, dinners, the rise of his own legend. He held Miles with two hands and imagined living long enough to watch this boy lead him down a hallway and ask for another story.

He hired a private investigator not to go after Mara—she’d made herself easy to find—but to untangle the past. The report arrived bound and neat, a story he already knew in parts but not in order: a lawyer who had seen an opportunity to punish a man who had humiliated him in court; a judge whose brother-in-law worked for a company that owed Arthur money; an ex-wife who had weaponized a lie so well she started to believe it. It didn’t matter anymore. The present was a baby who squeaked and a daughter who said thank you when she didn’t have to.

Mara’s fall was as gaudy as her rise had been. A company with an ethics policy made a show of letting her go. Partners called with regret in their voices and relief in their hearts. Tabloids did what they do: found an old arrest for a party she shouldn’t have been at and wrote about it like it had been a prophecy.

Arthur didn’t want her in jail; he wanted her elsewhere. His lawyers negotiated something that looked like contrition. Community service. Anger management. Therapy. A fine that wouldn’t bankrupt her but would sting, the way a hand slapping a cheek stings—a memory more than a wound.

Jordan pivoted to contrition too, as men do when their options shrink. He wrote a letter to Sienna that used the passive voice to remove himself from sentences. Mistakes were made. Boundaries were crossed. Emotions were high. He asked to meet the baby. She said no. He filed anyway. The hearing date came like weather.

Arthur’s lawyers sat beside Sienna in a room with carpet that tried to look expensive. The judge this time was a woman whose robe didn’t hide her posture. She listened. She asked fewer questions than Jordan’s attorney wanted and more than Arthur’s did. She looked at Sienna when she spoke and at Jordan like he was a homework problem she had already solved.

“Supervised visits,” the judge said. “No overnights. No introductions to partners. Counseling. Three months. We’ll revisit.”

It wasn’t what Arthur wanted. It was what Sienna could live with. As they left, Arthur opened his mouth to say something about fighting harder. She beat him to it.

“I want Miles to know truth,” she said. “That includes the truth that his father didn’t show up when it mattered—and that people can grow, even if I don’t plan my life around it.”

Arthur nodded. He thought of the door that had slammed on him twenty-three years ago and the quiet of the house he’d wandered around in afterward like a man in a museum after hours, unsure which paintings he was allowed to touch. He wished her mother could see her. He wished her mother could be different. Wishes were useless. He stuck to tools.

Part V — The Day After

Sienna’s new house wasn’t new; it had good bones and a yard big enough for a toddler to run dumb circles in someday. Arthur bought it and then remembered to ask if she liked it. She did. She liked the way the sun came in through the kitchen window in the morning and did not ask permission. She liked the creak in the third stair and the way the front porch dared the rain. She liked the idea of a garden she would let go wild.

She began to sleep. Not always. Not well. Enough to remember what mornings were supposed to feel like. She made coffee and used the good mug every day because there was no one to save it for. She held Miles and said things out loud she never would have admitted to anyone, and he, with his ancient face and new lungs, blinked solemnly like a priest and then burped.

Arthur came by with groceries and didn’t put them away wrong. He fixed a cabinet door that had decided to retire. He met her in the yard and handed her a pair of gardening gloves like a man presenting a crown. His assistants learned the route to the new place and stopped lingering near the curb like security so that neighbors would stop staring. He came as a father, not a benefactor.

They spoke occasionally about forgiveness. Not the abstract kind. The kind you use like a hammer and hope it lands square.

“Do I have to forgive him?” she asked one afternoon, Miles asleep across her chest in a way that made her shoulders ache and her heart expand.

“No,” Arthur said, and his answer was so immediate it startled them both. “You don’t owe him anything he can use to hurt you again.”

“What about her?” she asked, eyes on the daisies she’d planted. “Mara.”

“That’s not a debt, either,” he said. “Forgiveness is a gift you give yourself because carrying the other thing costs too much.” He paused, then grinned. “Also, a year of pushing dinner trays at a community clinic will likely finish the work.”

She laughed. It didn’t erase anything. It made room around it.

Arthur told her about the divorce in a series of sentences laid like a path you make so you don’t step on the flowers. He had been ambitious. Her mother had been tired. The court had not been kind. He had believed he could fix things by force. He had been wrong. He had been punished, and he had deserved some of it. He did not defend the rest.

She told him about growing up in a house that had three safe corners and one bad one, about the way her mother’s exhalations sounded like curses muttered into coffee, about the day she learned to lie well enough to protect someone who wasn’t telling the truth about being okay. She did not say she was glad her father had money now. She said she was glad he showed up.

They argued once, properly, the kind that ends with both people apologizing for things they didn’t actually do wrong. He had arranged something with a preschool wait list that made her feel like a person picked to go first for reasons she hadn’t earned. She yanked. He dug in. They both heard what the other was really saying. He dropped the list. She allowed him to arrange a fence repair because the dog had found a way under it and neighbors had opinions.

When custody day came, Jordan arrived in a shirt that said he was trying and eyes that said he wasn’t sure at what. He held Miles like a man borrowing a fragile thing. He cried. It was messy. Sienna didn’t let Arthur step between them. Some steps weren’t his to take. She sat in a chair in the corner of the room and watched the minute hand play its trick. She hated Jordan for making her feel like a guard and then hated herself for whichever part of her had once thought she could make him into something he wasn’t. She did not hate him in front of Miles. She would save that for after bedtime, when cursing into a pillow feels like lighting a match you don’t let burn anything down.

Jordan tried to be better for three visits. On the fourth he was late enough to make the supervisor ask him to reschedule. On the sixth he took a call during the hour he had, and when Miles fussed he passed the baby back to Sienna without looking up. On the eighth he didn’t come. On the ninth he arrived with a stuffed bear and an apology written in the handwriting of a man who had dropped out of English class when it stopped being easy.

Sienna kept a notebook. Not the petty one, the legal one. Dates. Times. Sentences not loaded with adjectives. When the judge asked for a status report, she handed it over without flourish.

Part VI — The End That Is a Beginning

Months bent themselves into a year and then another. Headlines found other sins to gnaw. Mara finished her service, kept her head down, and got a job that didn’t require the world to love her. She apologized once, in person, without flowers or cameras. Sienna listened. It wasn’t absolution. It was acknowledgment, paid in full and not with interest. They did not become friends. They nodded when they passed at the community clinic where Sienna had started volunteering on Saturdays after the baby stopped being an excuse to nap and became a person you bring places.

The hospital adopted a policy. Partners sitting with patients would later joke about the no-nonsense posters that went up in the waiting room. Zero tolerance, the first one read. It was not a threat. It was a promise a building had decided to learn how to keep. Arthur endowed a fund for patient advocates because money can be foolish or it can be precise. He chose precise. He did it in Sienna’s name and made sure the plaque was in a corner where only the right people would see it.

Miles learned to walk. He had the gait of a drunk emperor. He toppled into Arthur’s shins and laughed like he had invented falling. Arthur taught him to stack blocks and then to knock them down. He taught him to say “Nana” for the portrait of Sienna’s mother that hung in the hall, because that seemed right. He taught him to say “go” at traffic lights and “stop” at crosswalks. He never taught him the word “hate.”

Sienna discovered she was very good at two things she’d never had time for: growing tomatoes and running a spreadsheet for a nonprofit. She started a small foundation with Arthur’s seed money and her own rules: help women in crisis with things that don’t fit in donation bins—childcare during court dates, a locksmith when a door becomes a threat, a Lyft when a bus becomes a danger. She didn’t put her name on it. She didn’t tell stories about it to gain followers. When people asked what she did, she said, “I keep the wheels on.”

Arthur remarried, late. A librarian who said no to him the first time he asked because it amused her and then said yes the second time because she realized he meant it. Sienna liked her because she didn’t try to mother what was already mothered. They built a family that made no sense on paper and every kind of sense in soup.

Jordan moved away. The court modified the order. He asked to come back once, two years later, with a letter that sounded like a man who had finally met his own reflection and found it patience-worthy. Sienna agreed to a meeting in a place with cameras. He held his son. He told him a story about a frog. He didn’t make promises. He left without drama. That was, finally, enough.

On a spring morning, Sienna stood in her backyard and watched Miles push a toy truck through dirt he insisted was a construction site. Arthur leaned on the fence with a cup of coffee and the look of a man who had learned to take his victories slowly. The daisies pretended to be wild because she let them. In the distance, the neighbor’s wind chimes insisted on being included.

“Do you ever think about that day?” Arthur asked, not looking at her.

“Sometimes,” Sienna said. “Mostly when I walk past the part of the hallway where the paint is a little fresher.”

“I think about it less now,” he said.

“Good,” she said, then made herself say the rest. “Me too.”

He set the cup on the fence post and turned to her. “I was not there when you were small,” he said. “I don’t get to fix that. I do get to show up now.”

“You do,” she said. “Consider yourself hired.”

They laughed, the kind that rearranges your ribs a little. Miles toddled over with something that might be a worm and definitely was a gift. Sienna took it with the practiced ease of a woman who has learned to receive.

That night, after Arthur had gone home and the dishes were stacked to dry and the baby monitor hummed a sound that acts like prayer, Sienna stood at the window and looked out at the dark yard. She touched the glass lightly, as if checking for rain. She whispered to the sleeping house the words that had become an oath and then a habit and then a promise she finally believed:

“You are loved. You are safe. You will never know the pain I did.”

She turned off the light. The house breathed. Across town, an old man sat in a chair and let gratitude do the work of forgiveness. A woman who had done a terrible thing filed a report at work and then stayed to clean the break room because the person who was supposed to had called in sick. A man who had made himself the center of a story he didn’t deserve learned to exist in his own small circle without mistaking it for a stage.

It wasn’t revenge that saved anyone. It wasn’t money, although money built the fence and paid the lawyer and put the right names on the right lines. It was a hand on a forearm in a corridor, a voice in a delivery room saying I’m here, a grandfather in a midnight chair, a mother who learned that kindness is not the same as weakness and that forgiving isn’t forgetting; it’s letting go of a rope and realizing your hands still work.

That was the clear ending: a family built around the truth instead of the performance. A city that remembered for one news cycle and then forgot, as cities do. A little boy whose first word was “go,” whose second was “Nana,” and whose third was a name he gave to the dog he loved, which was really about joy and not about history at all.

And if anyone asked Sienna years later what changed everything, she didn’t talk about the slap or the cameras or the hospital corridor or the name that made doors open. She said, “A promise kept,” and left it at that.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

An Unknown Number Called Me It Was His Ex What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew

An Unknown Number Called Me. It Was His Ex. What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew Part…

The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law

The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law Part I —…

I GIFTED MY PARENTS A $425,000 SEASIDE MANSION FOR THEIR 50TH ANNIVERSARY. WHEN I ARRIVED, MY MOTHER

I gifted my parents a $425,000 seaside mansion for their 50th anniversary. When I arrived, my mother was crying and…

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am Part I:…

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side?

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side? Part I — The Unicorn…

“We’re Taking Your Lake House For The Summer!” Sister Announced In A Family Group Chat. I Waited…

“My sister said, “We’re taking your lake house for the summer,” and everyone in my family agreed. They drove six…

End of content

No more pages to load