The Family Of My Daughter-In-Law Pushed My Grandson Into The Lake… But They Didn’t Know My Brother

Part I — The Water Was Gold

The morning at Silverpine Lake was painted in the kind of gold that makes you forgive your own life for a while. The light scattered in pieces over the ripples; the breeze smelled like wet cedar and new bread from the village bakery across the road. My grandson Ion ran along the wooden pier in his red rubber boots, a small boy with a red toy boat and a laugh that kept stitching my heart back together each time it tore.

“This is the fastest one they had,” he told me, holding up the boat like a medal. His hair stuck up in cowlicks; his cheeks wore the kind of pink that only belongs to children and saints.

“It will win every time,” I said, because with grandmothers, predictions can be miracles if you say them gently enough.

We were there because my daughter-in-law, Maywish, had suggested it. It would be “good for Ion to spend time with her side of the family,” she said, her eyeliner perfect, her mouth a line drawn by someone who had never considered softening. The Raheems—her mother Rabia, her brothers, their wives—were already at the lake house when we arrived: a gleaming new structure on the hill with glass that made the pines hold their breath. They stood on the deck in polo shirts and practiced laughter, holding the lake like a photograph.

They never liked me. To them I was the poor, stubborn remainder from a chapter they wished history would forget—the widow with a headscarf and a spine, still tethered to the son who had died and the grandson who refused to erase him.

But Ion wanted this day, and so did I. The lake and I have known each other for a long time; it has seen me when no one else was looking. “You should rest,” Rabia said to me, gliding across the grass in sandals that did not belong to earth. “We will take him. He loves water, doesn’t he?”

“He can’t swim,” I said. “He stays on the shallow end or the pier. And only with me.”

Her lips stretched into what passing birds might mistake for a smile. “My sons will watch him,” she said, and the sons, all handsome, nodded their heads in loose circles without looking at me. “Mama, please,” Maywish chimed, a practiced sigh in her voice, “you worry too much.”

There’s a hinge inside a person where intuition swings. Mine creaked that morning. But Ion was hopping, his boat already in the water, and I thought—be generous, old woman, don’t sour the air with your fear.

I watched them walk down the slope—the immaculate family, my little boy in his red boots—until the moving shapes became colors and the colors became nothing. Then I washed tea glasses and folded blankets and told the trembling piece of myself to lie down.

Half an hour later, the world ended without warning.

Screams carry differently over water. They come curved. A man’s voice, then two more. A splash. A woman shouted Ion’s name in a tone you use for lost keys. I ran. My shoes didn’t matter. My old bones didn’t matter. The distance collapsed under me until I arrived at the pier and saw my grandson’s red boat bumping against a post, ownerless.

“Ion!” My voice cracked the surface like a stone.

He floated face down three meters from the end of the pier, small body in too much water. Someone jumped, but too late, everything was too late. They pulled him out and he collapsed into my arms, not a boy but a weight that would haunt the shape of my shoulders even in sleep. I began compressions. I breathed. I begged. I tried to persuade God with bribes and bargains and threats that were not in my nature.

Rabia cried with sound but without water in her eyes. One of her sons tried to call an ambulance and got the number wrong twice. Maywish stood on the pier, hands shaking, eyes locked on me, not with grief but with the cold voltage of guilt recognized and denied.

At the hospital, machines hummed like a mockery of lullabies. I held Ion’s hand and told him stories about the time his father used to race dragonflies on this same lake and always lost. I waited for a small twitch, a rebellion against the exit, but Ion never learned to fight in that way—he trusted water and people and promises. He could not imagine a world where any of those things betrayed him.

A doctor in a clean white coat told me my grandson had gone somewhere no machines could follow. He clasped my shoulder the way people clasp old hands when words feel like furniture. I stood and nodded while the room folded around the edges. In that bend of space, I heard a voice behind me that pulled time back like a curtain.

“Who did this, Hina?” said my brother.

I turned. Arif has carried silence like an inheritance his whole life—a man whose compassion arrives quiet and whose fury arrives colder. He lifted me once when I was ten and some boys had thrown stones at my headscarf; he told me then that the world was small to men who laughed at pain, but large to men who carried it. We had not needed many words in five decades. We did not need many now.

“It was an accident,” Rabia would say later. “Children, water, summer—it happens.”

But in the moment when my brother’s hand found my back, we both knew accidents do not leave guilt clinging to a daughter-in-law’s throat like perfume.

“Don’t cry,” he said into my hair. “They think they broke you. They don’t know me.”

The storm began at once.

Part II — The House of Glass

There is a grief so raw it scrubs memory down to its bones. For a week I lived inside that grief—waking with Ion’s name on my tongue, sleeping in a house where everything was suddenly the wrong size. The Raheems sent food and flowers heavy enough to make tables bow. The smell of lilies made me nauseous.

Arif did not move his chair far from mine. He answered the phone and made the arrangements and then, when the door finally closed each night and the casseroles became cold memorials to their own generosity, he opened a notebook and began writing. I grew up in a village where men kept their secrets in the soles of their shoes. My brother—and I would only learn the exact depth of this months later—kept his inside corporations, inside law firms, inside the phone numbers of men whose names never appeared on the glossy pages of magazines but whose signatures mattered more.

“Tell me,” he said, and I told him.

I told him about the way Rabia’s eyes slid off me like oil slides off water. About the stories in that household—the way they rewrote the death of my son into an inconvenience, the way they made Ion small on purpose. I told him how they insisted on taking the boy to the lake without me, the way the men had moved slowly when the water went wrong.

Arif listened without flinching, then began asking the kind of questions that gather justice like dry sticks gather flame. What time? Which brother? Which angle of the pier? Who had asked you to rest? He asked for names, for times, for phone numbers. He called people with those numbers and some of them started talking as if they had been waiting their whole lives to be asked.

The first thing the world learned about my brother was that he had investigators. He said it the way one would say, “I have sugar,” and for a week they moved like shadows through office buildings and banks and servers. They came back with pieces: a fake charity with checks written to a cousin who had never seen cancer; a shell company whose only purpose was to hold a car the color of a bruise; a land deal signed by a man who lived in Dubai but somehow attended a meeting in Lahore the same day. Thin places where truth showed through.

Arif laid the papers on my kitchen table one evening, neat stacks that smelled like toner and saltwater. In the legal language, the Raheems had built their empire on wood that rotted from the inside. In the language of my childhood, they had spent years laying their pride on beams that would betray them.

“Not destroy,” Arif said, when I asked if this would end them. “Expose.”

There is a cruelty to revenge that excited me in those days. It would have been easy to give in to it—to become the kind of person who uses blood to wash blood. But my brother had no appetite for that. He preferred consequences that leave rooms clean.

“We will give them truth,” he said. “And if they drown, it is because they never learned to swim with anything heavier than a lie.”

We began. Or perhaps the world had been waiting and only needed one small shove.

Part III — The Push

The first headline arrived like a dove that had flown all night and had not eaten—breathless, trembling, unavoidable.

RAHEEM GROUP UNDER INVESTIGATION FOR TAX EVASION, FRAUD.

The next day: CHARITY FUNDS FUNNELED TO SHELL COMPANIES, SOURCES SAY.

A television van parked two houses down and pretended it was there to film the weather. A journalist called my phone three times; I said nothing. Arif said everything to the right people—the tax director who still believed numbers are sacred, the young prosecutor with a new baby and a nervous habit of re-arranging paper clips, the old judge who remembered what honor feels like when it is still warm.

The Raheems were powerful, but power that never had to lift weights cannot run far. Bank accounts froze. One brother was taken in for “questioning,” which is the polite word for a room with no windows and a chair that makes your back confess things your mouth does not. Lawyers arrived like sea gulls over garbage. A gardener who had mowed their lawn for eleven years confessed to having nightmares and agreed to tell the police that he’d seen what he’d seen: a hand on Ion’s small back, a push, a pause. A lake swallowing my boy. Thirty silent seconds while men rehearsed their screams.

That clip of the gardener’s testimony played on the news once. He wore a cap and covered his mouth with his hand when he spoke the word “push.” I turned the TV off and walked into the garden and screamed the word for myself, out loud, into the air, because there are moments when sound is the only thing that can keep you from coming apart.

Rabia called. Her voice was full of air and then water and then the gravel that comes after begging. “We have always been friends,” she said, as though speaking a spell. “Let us make peace like family.”

“Peace?” I asked. “You wanted me to rest.”

“Hina,” she sobbed, and I could hear the room around her—men moving like ants, glass set too hard on marble—“please, please.”

“You pushed him,” I said, calm now, because rage tires you faster than a sprint. “Your sons pushed him. And you taught them how.”

I hung up.

Arif doesn’t smile much, but he smiled then. Not with delight, just with acknowledgement that a piece had moved and the board now looked inevitable.

The day the tax officers walked into the Raheems’ headquarters with clipboards and squared shoulders, I went to Silverpine Lake alone. It was early and no one else was there. The pier was wet. A heron stood where Ion used to stand and looked at me with prehistoric patience. I thought of the red boat. I thought of the child who had held it. I put both my hands on the water and said the only prayer I knew that didn’t sound like a bargain: Let my boy be remembered for his laughter and not the way his lungs emptied.

The media made noise, but the courtroom made quiet. When the judge finally spoke, it was with the exhaustion of a man who has had to say the same things to too many people for too many years.

He used numbers. He used statutes. He used the phrase “with malice aforethought” and looked at me when he did. The brothers were sentenced. Rabia, who had smiled at me and asked me to rest, was led from the courtroom with a hand on her elbow—the first time a hand had ever held her for something other than affection or advantage.

In the front row, my daughter-in-law shook the way people shake when they know the floor is finally telling the truth about their weight. She asked to speak and the judge let her. She said “accident” four times. She said “God’s will” twice. She said “we loved him” once, and the old judge flinched as though love were a weapon someone had tried to smuggle into his court. Then Arif’s lawyer played the gardener’s clip and the room became a lesson in the kind of silence that saves.

When it was over, someone put their hand on my shoulder. It was the young prosecutor with the nervous paper clips. “I have a child too,” he said, and his voice broke the way the lake had broken. “I wish I could fix this.”

“You did,” I said. “You are the reason some other boy will come home wet only from rain.”

He nodded and looked at his shoes as if they were an apology.

Part IV — Ion’s Haven

We could have taken the lake away from everyone. We could have put up a fence and a sign that said PRIVATE and let Silverpine collect dust and ghosts. It would have been easy. It would have been satisfying. But Arif had a different idea.

We bought the parcels around the quiet end of the lake where children go when their parents are tired and still want them to be happy. We talked to the council. We made promises. We wrote checks. He hired a landscape artist who builds parks with his dead brother’s hands and a carpenter whose father used to be a pirate in the way fishermen tell it. We replaced boards. We installed railings. We hired a lifeguard who can tell the difference between laughter and danger from very far away.

The sign went up on a Monday morning after it had rained the kind of rain that makes the air feel forgiven. Ion’s Haven, it said, in letters that would be easy to read even when your eyes are full of tears you don’t want your children to see.

They came. Strollers and scooters and tired women with strong shoulders. Teenagers stolen from their phones by water and wind. A boy with hearing aids who sat so close to the shore that the lake might teach him a word without using his ears. Children launched boats—yellow, green, blue. I brought one colored red, because memory can heal if you hold it with open palms, and I slid it out onto the skin of the world.

Arif stood with his hands in his coat pockets and watched. He doesn’t say words like good often. He said it then. “Good,” he said. “This is good.”

There is a difference between revenge and justice that I had never had to keep straight before. Revenge is an arrow. Justice is a net. One punctures. The other holds. I learned to live with the net.

Most nights now I sleep. I still dream sometimes that Ion comes wet and furious to my door and scolds me for not making him wear his life jacket. In the dream I tell him that he is seven and my job is to make sure he doesn’t drown, not to let him teach me what happens when he does. And then we both laugh and I wake up feeling like my bones are a little less heavy.

On the anniversary of his death, I went to the park before anyone else. I sat on the bench with the dedication plaque and thought of all the things grief takes and all the things it leaves behind. Arif appeared at some point—he moves like weather when he needs to—and put a paper bag between us. It had sesame bread and an orange inside.

“If you want to cry, cry,” he said. “But we eat first.”

We ate. We watched the water. A dragonfly landed on my knee and I said hello. Arif does not believe in omens, but he did not move until the dragonfly did.

A woman approached with a child’s hand damp in hers. The boy tugged away, pointed at the red boat under glass in the small case near the bench and shouted, “Mine is like that!” His mother told him to be quiet. I told her he never had to. “That boat belongs to every noisy child,” I said. “Especially yours.”

She smiled that tired, grateful smile women wear when strangers are kind to them at the exact right moment. “Thank you,” she whispered. “We needed this. We didn’t have anywhere to go after…” She stopped, and her mouth did something that looked like a broken thing trying to become a bird. She didn’t need to finish. I nodded. We sat together long enough to pretend we had always been friends.

When she left, Arif leaned his head back and closed his eyes. “You know,” he said, “they didn’t think of you once when they decided what to do that day. They did not calculate you. That is why they lost.”

“I know,” I said. “And yet I still think of them sometimes when I am stirring tea.”

He opened one eye. “You’re allowed to,” he said. “Remembering is how you know you’re not them.”

Part V — What Comes After

The court cases ended. The news vans went away. The men in the suits who used to sit in front pews at the mosque quietly changed seats. There is a part of me that will always pause when I hear a body hit water. There is a part of me that learned to laugh again anyway.

Months later, a letter arrived from the prison. The paper was cheap and the handwriting unfamiliar but trying very hard to be pretty. It was from my daughter-in-law, addressed to Ammi, which means mother in a language we used sparingly with each other because we had never agreed who got to be one.

She wrote, “I cannot ask you to forgive me. I practice saying his name out loud now. Ions. It is the only prayer that doesn’t rot in my mouth. I will die with what I did. I hope you live with what you made—a place where children do not.”

I did not write back. There are silences that respect more than words can.

Arif never asked me to. He does not ask me for much. He took my spare keys to his house and made a copy and then pretended it had always been mine. Somewhere between the audits and the headlines I realized my brother is more than the sum of all the ways men teach girls they can be saved. He is the scent of cardamom on a winter morning; he is a file folder full of the names of men who will answer when he calls; he is the person who watched me turn my pain into a park and told me I had done a good thing.

I do not know what happens after “after.” I only know that the lake and I are old women together now and we have forgiven each other. I bring the children snacks. I tell their mothers where the lifeguard keeps the extra towels. I sit on the bench under the cedar and think the kind of thoughts that used to scare me because they were too quiet.

There is a rumor people like to repeat about grandmothers—that their hearts are made softer by time, padded by cookies and fairy tales. Mine was sharpened by water and paper and a brother’s name. It was padded, too, by the small warm palm that used to fit inside mine like it was made for it.

They pushed my grandson into the lake. They did not know my brother. They did not know me.

The lake knows us now. It carries our names like stones in its pockets—heavy, honest, and at rest. And every red boat that glides over it is a small, ridiculous, beautiful triumph over all the ways we learned to drown.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

CH2. My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me

My Daughter Betrayed Me… But My Late Husband Saved Me My daughter thought she could take everything—my beach house, my…

CH2. My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed…

My Family Skipped My Child’s Surgery, Then Demanded $5,000 — and Called the Bank When I Laughed… Part I —…

CH2. After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not worth the trouble,” she said. I cleaned toilets for money. Monday, a detective found me: “Your real father in Germany spent millions searching for you. He left his automobile empire worth $2.1 billion -to claim it, you have 72 hours to your family’s darkest secret”

After my mother chose my stepfather over me, I was forced to live on the streets at 16. “He’s not…

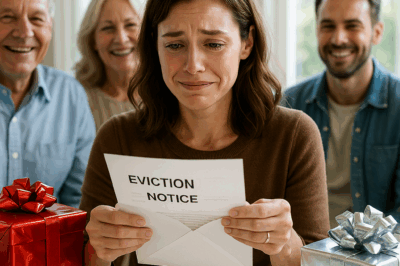

CH2. On My Birthday, My Family Gave Me A ‘Special’ Present. When I Opened It, It Was an Eviction Notice for My Own House. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding Day…

My Family Gave Me an Eviction Notice on My Birthday. I Smiled as I Returned the Favor on Their Wedding…

CH2. My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed…

My Dad Sent Me $3,500 Allowance But Mom Sent It to My “Golden Sister” for Her Dream—Until I Collapsed… …

CH2. At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake

At 27, My Parents Tried Controlling Me Again — Big Mistake Part I — The Invitation With a…

End of content

No more pages to load