After I became a widow, I never told my son about the second house in Spain. glad i kept quiet…

Part One

My name is Clarissa Morgan. I’m sixty-three. Three weeks ago I buried my husband of thirty-eight years, Edward. We built this house together, raised our children here, watched the seasons shift through the kitchen window, drank tea in the mornings and argued about thermostat settings at night, planted roses along the fence every spring. This house had the sound of our lives stitched into it: the creak in the third stair, the scuff mark where Brian’s bike had once clipped the wall, the dented coffee table where Danielle had dropped a casserole and we laughed until the sun went down. When Edward died, the house felt both too full and painfully empty.

The funeral arrangements required a kind of calm that was strange to me. People offered the right words. The neighbors brought food and sympathy. The church smelled of lilies and wax. I moved through ritual with a polite, mechanical grace: flowers, signatures, plates of lukewarm sandwiches eaten at the kitchen island between condolences. I said thank you to the people who said I was brave. I said, of course, to the minister when he asked whether I wanted the service public or private. I let the undertaker do his work without hovering—because that was the sort of thing Edward would have wanted, the quiet dignity, the small logistics done right.

Then the calls started.

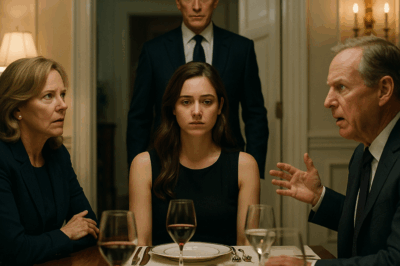

“Mom, we need to talk about the house,” Brian said on a Tuesday morning, straight into the business of me. His voice had that calm, efficient firmness he used back when haggling contractors in college. He’d always been steady; when he wanted something, he presented it like a proposal. He did not ask. He told.

I stood at the counter, staring at the coffee in my mug. It had been Catherine’s gift—“World’s Best Grandma”—a bright, cheerful thing that suddenly felt foreign in my hands. The grief still lurked in the room like a draft under a door; the vase on the table had been heavy with funeral flowers yesterday, a little flaccid now. A lifetime of shared habits—where the teaspoons lived, how elbow grease cleansed brass—had turned into a map of small bereavements. Brian’s words were another map, and it led somewhere I did not want to go.

“It’s not sustainable,” he said. “That house is too big for you. You should downsize.” The pitch was delivered like a structure: problem, proposed solution, benefits, timeline. He and Danielle, he explained, had discussed it over dinner. They had suggested selling the house. They had a buyer—Gregory, a realtor friend—who could close quickly. They promised a win-win. We’d all take a percentage. They’d be generous. They painted a tidy scene like it was charity.

“Where would I go?” I asked, and even to my own ears I sounded tired.

“We thought—” Brian began. “Danielle has that finished basement. You’d have your own entrance, your own bathroom. It’s cozy.” His voice slid into the word cozy as if it were a comfortable glove he was already putting on. He didn’t mention the flood that came every spring in Danielle’s basement, the one Danielle’d fixed for six months the year after the tornado. He didn’t mention that the “cozy” space had poor light and a heater that rattled.

“It floods,” I said. It was not a question.

“It’s been fixed. We can make it nice for you. You’d be close to Catherine. She could help.” The last was pitched like a concluding flourish: family-care, convenience, moral righteousness. It felt rushed, rehearsed. I remembered Thanksgiving when I had been seated at a different table, down a few steps, where a folding card had said FAMILY—like an afterthought.

That evening Danielle texted me: Mom, Brian told me about the house. I know it’s hard, but it’s for the best. Catherine is excited to have Grandma closer. Can’t wait to talk details.

Catherine—my granddaughter who used to make flour puppets on my kitchen table and write note cards with tiny hearts—hadn’t called in months. She’d been busy with college and internships, and I had not wanted to press. Now someone spoke for her and in the voice of a daughter who hadn’t made the time to sit by my hospital bed and hold my hand when I’d called at night and said I couldn’t sleep because the house was so quiet, and the words felt like ledger entries.

By sundown I realized I was furious in a new way: not the sharp rejoinder that comes when someone insults you in public, but a slow, steady, hot realization that I had been cataloged as an asset rather than as a person. I’d spent decades tending the family life—meals, calendars, birthdays, the awkward PTA bake sale table—while cracks in conversation and in closeness were smoothed over with a “she’s fine” that read like a ticket to erasure.

That night I sat in Edward’s study. The room still smelled faintly of his aftershave and old paper, a comforting scent I’d once thought would be my last forever companion. I opened the bottom drawer where he kept boring paperwork. Among tax returns and an old stack of gardening catalogs, a navy folder pushed into my hand. I fished it out and the weight of it told me nothing at first—bank statements, investment summaries, and a deed that made my breath catch.

A whitewashed villa with blue shutters in Marbella. Photographs slipped between pages: a sunlit terrace with lemon trees, a small garden lined with bougainvillea, the sea a bluish smear in the background. On the back of one photograph: a note in Edward’s impeccable handwriting—A place where no one needs anything from us, just peace. Dated six months earlier.

There was an envelope with my name written on it in that same deliberate hand. A letter waited: My dearest Clarissa, if you are reading this, then the silence I tried to spare you from has arrived. I read the letter carefully, twice. The words were simple and direct, patient and exact—everything he had been in life.

He wrote that he knew me—had known me in that way a spouse can know the unspoken shapes of a person. He wrote that he had seen the way our children circled the family finances. He wrote that he loved them, but that he loved me more than the tidy consensus of people who take over another person’s life when grief makes them timid. He had set things in order. He had bought the house in Spain secretly, on the side of a life he wanted for us when we were older; he had placed it in a trust for me; he had made sure it was paid off. He’d opened an “independence fund.” He had sorted it all, because he was, as he had always liked to joke, “tedious about kindness.”

I slept little that night. Edward’s generosity was not new—he reserved little acts of thinking for me all the time—but this was an act at the scale of leaving a small map for survival. That morning I sat in an attorney’s office across from Connie West. She smelled of leather and quiet competence. “Your husband was meticulous,” she told me as if revealing the last of the clues in a small mystery. He had created a revocable trust in my name; all assets were mine. The Spanish property was deeded to me. The life insurance went to the children; the rest—our house, the investments—was mine to do with as I pleased. A second envelope slid across: a fifty thousand dollar account Edward had built for me to use if I chose. He had expected my grief and made provision for my stubbornness.

I felt a small, fierce gratitude the likes of which I had not expected. The shock was always that someone else had seen me as I had once been seen: strong, competent, capable of deciding. In Connie’s office, the lawyer’s soft, authoritative voice with its catalog of legal facts read like a permission I did not know I’d been waiting for: you can go.

When I organized movers two days later, I wore the red dress Edward had always said made my eyes sparkle. I packed a box labeled “important” and another labeled “kitchen — favorites.” Brian screeched into the driveway before the truck was halfway loaded, stepping out of his car with a folder thick with what he thought were decision documents—buyer’s forms, schedule of valuations. He didn’t knock. He—efficient, corporate—began by asking whether I had signed anything. He was already mentally hunched over the spreadsheet of money that would come.

“You can’t sell the house without talking to us,” he said. I met his eyes and said, calmly, “I don’t plan to sell it.”

He blinked, as if being blindsided by someone who had the wrong powerpoint. “Mom, we were trying to help. This house is a burden. We’re being practical.”

“You were being practical about me like I’m a monthly line item,” I replied. “You were not planning with me. You were planning without me.”

He tried the old lines—practicality, empathy disguised as logistics—but the truth was clear in his voice: their certainty had not included me. I packed a box labeled “Family things — give to Brian” and another labeled “Memories — not for sale.” I left the childhood toys in the attic where dust could sit on them; those things were not currency.

That afternoon I boarded a flight to Madrid, clutching Edward’s letter like a talisman. He had arranged a caretaker, Pilar Rodríguez, and a property manager who would ensure the house was ready. When I stepped into the air that smelled a little like travel and possibility, I felt something loosen. The decision was not dramatic. There was no shouting, though there could have been. There was simply a clarity like sunlight: my life had been rich; it would not be consumed by other people’s convenience.

Spain was luminous. The villa looked as if the photographs had been made from truth: white stucco, cobalt shutters, a terrace that faced a soft sea that kept a steady, calming rhythm. Pilar hugged me the way people hug when they have been entrusted to be kind. Her Spanish was lyrical; her English was welcoming. “Your husband wanted this to be a gift,” she said. “He said, ‘Pilar, make sure this place is ready for Clarissa. She is going to understand it.’”

For days I let myself be small in the way of someone who has carried the weight of housekeeping for decades: I learned the names of the lemons, the rhythm of the baker down the street, how to choose fish by the clarity of its eye. I walked until my calves ached in the morning, breathed Mediterranean air into my chest like it would fix the places where grief had set up camp. The house was quiet in the good way—quiet like the hush that follows rain. I made lists I’d never had the time for: things to write about, recipes to try, letters to send. It felt indulgent and necessary.

When I finally called Brian, he answered on the second ring. “Where are you?” He sounded sharp. That was the point when the line between curiosity and control seemed to fray and I realized how much I had been given back by being kept out of the accounting of my life. “Spain,” I said. “I’m at the house.” There was a pause filled with every possible unspoken accusation—why hadn’t I told him, why hadn’t I mentioned this before, how dare I keep secrets.

“I wanted you to have it, Clarissa,” Edward had written. That sentence could not be undone by a phone call.

Brian said he was coming over, that we needed to talk. “Now?” I asked. “No, you can keep the house if you want,” he blurted. “We can…look into options.” He sounded dizzy and small for the first time, as if someone had taken away his map.

I didn’t return. I let the distance be a kind of scaffolding. From the terrace I could see fishermen casting nets in the early morning and children with scooters in the lane below. I made myself tea and wrote the opening paragraph of a memoir I had never had time to write. I walked with Pilar to the market and learned the name for the local cheese.

On the fourth day, Catherine called. She sounded different than in the group texts and social media. She had been the one who used to build forts of blankets with her cousin on the living room floor; she had also been the one who’d been busy—college, internships, relationships—and had left adult things to parent and sibling. Her voice was raw. “Grandma,” she said, “I didn’t know. I’m so sorry. I thought…we thought you were fine.”

“I’m fine,” I told her. “I’m more than fine. I have a house where lemon trees grow.” Our conversation was long and honest. She told me how uncomfortable she’d been when I was sidelined at Thanksgiving, how she had misread my silence as acquiescence. She asked if she could come for spring break. I said yes without hesitation.

When Catherine arrived, she looked less like the polished images I’d seen on Facebook and more like herself: plain jeans, a messy bun, eyes that sought mine and held them. She walked across the terrace like she belonged there. It was a balm to have someone who wanted the story rather than the consolation. We wandered the village streets, went to the market, cooked together, and finally lay on the terrace at dusk telling each other things neither of us had been sure how to say.

I had kept the secret of the house because Edward had kept it for me. In quiet moments, I thought about that secrecy—not the sly, petty kind, but a careful form of protection. He had known our children well enough to understand how grief could be weaponized into steering, how love could become a justification for taking control. By keeping the house a secret in his final months, he had given me an unassailable piece of autonomy. When I reopened the shutters and found the sea still there, I realized what that autonomy felt like: a place to breathe and a chance to reengage with the world on my own terms.

That first month in Spain became a soft kind of reclaiming. I wrote. I cooked. I taught myself a version of Spanish in halting phrases. I tended the lemon trees with Pilar. I read letters I had written to Edward over the years and had never sent; I wrote new ones just for myself. Friends back home texted and called: the neighbors, Ellen who baked pies and cried easily, Donna who’d helped put arrangements together; they all expressed delight and envy in small, wistful ways.

Brian visited once—angry at first, then embarrassed, then apologetic. I listened. I told him about the trust. I told him the house was mine. He learned the legalese and took it hard. Danielle called less. There was a long silence with her; she struggled to parse how she had been part of a removal that now looked small in the light of what had been planned for me in secret. She apologized in a way that was both sincere and defensive. Time, not a contrite sentence, healed these things.

By keeping the truth secret, Edward had allowed the gift to breathe before it could be handled like a bank account. I had a new rhythm. And for the first time in years, I felt like the primary architect of my life again.

Part Two

Living in Spain did not erase grief. I missed Edward in tiny, stubborn ways: the way he would call me at odd hours to tell me a fact about oak trees; the toast he would burn when distracted and then declare that he had “improved” it by charring. I missed the small anchors of having spent nearly forty years with someone who knew me like a home. But what replaced the ache was not numbness; it was a sense of purpose and possibility.

Catherine turned out to be the most delightful companion. She was present in a way that felt like a mirror and a teacher both. She loved nothing more than sitting at my kitchen table with a stack of my old recipe cards and trying to make sense of shorthand like “simmer till reduced” or “heat till aromatic”—instructions that had once been passed along in our family like traditions. She hung curtains, painted a little sign for the garden, planted basil in a small pot that thrived in the morning sun. She asked questions that made my memories seem like treasures rather than relics.

We forged a life that was both quiet and social. I met other expatriates: Joanne, a retired teacher from Scotland who knit sweaters for the village dogs; Javier, a potter who made bowls I wanted to eat out of; Pilar’s cousin who ran a tiny gallery of paintings. I began to teach an English writing workshop at the local cultural center, a small group that loved the way stories felt when they were shared in the middle of an afternoon with a cup of espresso and the sea wind.

The village grew used to the woman with the lemon trees. The baker learned my preferences for bread. The fisherman nodded across the pier. The small, important rhythms of community stitched into me in a way that felt maternal without being demanding. I had come to Spain to heal. I had stayed because I could see a life built out of ordinary joys.

Meanwhile, news began to travel back to home. There were small legal entanglements—Brian and Danielle tried to contest my ownership. They hired a lawyer for a while, sent letters questioning trust formalities and claiming undue influence. But Connie West had been precise; Edward had been exacting in his paperwork. The trust had been clear and valid. The courts required proof of impropriety, and there was none. The only thing the legal process did was open wounds that had been left unbandaged; there were angry letters and terse emails. The law is blunt; it either judges by the paperwork or it does not. In this case, the paperwork was meticulously kind.

There was no court drama. There were no scenes of public spectacle. There was a kind of weary relenting, like an old argument that had slid into the past because the present will not permit it to continue. Brian had to accept the truth that his assumptions—about his mother’s finances, about what she needed—were wrong. Danielle had to admit that treating me as an appendix to her life made me disappear. Both of them learned, sometimes with embarrassment, the slow commerce of apologizing.

There were human consequences. A few of my neighbors were proud of my independence and wrote letters of support when the legal letters arrived. Some of my children’s friends assumed the house would be sold and their expectations had to be recalibrated. Those who had seen me as a resource learned a harder lesson: that people, despite being mapped in family systems, have inner lives not automatically ceded to others.

It would be too tidy to say that all was forgiven quickly. Forgiveness is a gradual festival of small days. There were dinners where we sat and said things like, “I didn’t see what I was doing.” There were long silences where old hurts breathed like ghosts. But there were also gestures: Brian sent a check for a memorial bench at a local playground where Edward used to read newspapers; Danielle sent an old casserole my mother had made for the first time after they mended a fracture. I took both gestures and turned them into a new grammar of love—one where I accepted apologies but did not return to the dynamic that had rendered me small.

Back in Spain, Catherine made a plan for her life that involved more staying than leaving. She changed her spring-break plans and then stayed longer. She began to take online classes remotely and did odd jobs at a café on the lane. The two of us built a small routine—bakeries at dawn, writing in the afternoon, swim in the harbor if the weather permitted, long conversations where we traded secrets and recipes and bad jokes.

I also began to write in earnest. The memoir I had started in the first week of my stay turned into a project I treated with the same meticulousness I had once applied to flower beds. I wrote about grief and marriage and the way people can feel like landscapes you’d grown up inside of. I wrote about Edward’s quiet acts—the notes in his pockets, the small interests he protected for me—and how those acts added up to something like love.

One morning, when the lemon trees were heavy with fruit, I opened email from a small independent press. A memoir competition, they said; send us your work. I sent the first draft. They replied with a gentle note: we love your voice. Would you consider revising? The work that had once been a hobby in late hours became a vocation. Friends in the village offered to proofread; Catherine read the whole thing and cried at the end—real tears that made my heart loosen in a way I had not anticipated.

There is a particular pleasure in being surprised at one’s abilities. I had been defined for so long by domestic competence—meals, schedules, passing on good recipes—that to be told I had a voice felt like finding a spare key to an unlocked door. Writing did not replace any of the losses, but it allowed me to sit with them differently. Words rearranged memory into story, and story is a kind of healing.

Months passed. Winter in Marbella is soft compared with Ohio. The fishermen moored nets earlier in the season; the cafés closed a little earlier. The house threw long shadows in the late afternoons, and I planted bulbs in the fall with Pilar and a glass of wine to mark the ritual of planting for future joy.

One summer evening I returned to Ohio for a memorial planting in the garden at our old home. I was not returning to live. The house stayed in my name, maintained and occasionally aired by local caretakers when I was absent. I came for the roses and the friends—that small patch of life that had been our joint legacy. Brian and Danielle were there. Their children were older in ways I found bittersweet: brash, quick, beautiful.

We ate at a long table outside, with plates of food that felt like home. There were awkward jokes and comfortable silences. At one point, Brian took me aside. His face had that tired young look men get when they have been proved wrong by a better story. “I was an ass,” he said, blunt and direct. “I thought I needed to take charge. I thought I was protecting you. I was wrong. I’m sorry.”

Those are not the most dramatic words one can hear—not Shakespeare’s thunder—but their honesty was clean. I told him what had been told to me long before: that protecting someone does not mean diminishing them. He listened as if he needed to learn the lesson for the first time. Danielle found me later and hugged me long, a hug that said everything a formal apology never could.

We did not sweep the past under a rug. We made rules. Visits on my terms. Calls once a week. No economic messiahing. No surprise plans about selling property. I asked them to treat my decisions like decisions, not emergencies—because that was what they were. They agreed awkwardly and then with relief. The agreements felt like a map.

Back in Spain, things settled into a sweet rhythm. Catherine enrolled in classes and took on a job at a gallery down the lane, and I taught my English workshop. People in the village started asking me to cook for small gatherings—the British women who ran the book club called me “the quiet one with the lemon cakes.” The life I had wanted did not come all at once. It arrived in pieces—an afternoon in the market, an accepted essay, the way a neighbor would open a bottle of wine and invite you to sit.

It would have been satisfying simply to remain in that quiet life, to have the story close with a neat bow: widow finds island paradise and granddaughter comes for tea. But life is fuller. One autumn morning I received a letter from a small foundation in my old county—they’d read my piece in a local newspaper about elder autonomy—and wanted to talk about sponsoring a small program to help seniors maintain independence in their homes. The irony was lovely. I had been given back my life by a man who had quietly understood the need for private dignity; now someone wanted me to help other people keep theirs.

I spoke at a small gathering in the town hall back in Ohio. I told the story plainly: how grief can be instrumentalized into decisions for us, how careful people can be about controlling the lives of those they think vulnerable, and how small acts of stubbornness—like a done deed, a trust signed in proper legalese—can provide the space for someone to live a life later on their own terms. People listened. Some were angry, some were nodding with the raw recognition that comes when you’ve been in the room and have had plans made for you without your consent.

I do not claim an especially heroic arc. There was no cinematic moment where I stood and declared independence to a gathered audience and then strode into the sunset. The most radical thing I did was accept a house, a trust, and the idea that my life could be arranged around my choices and not around other people’s anxieties. That acceptance required stubbornness and patience. It required me to be quiet—ironically—but that quiet was not passivity. It was a choice to preserve something that would be of enduring value.

When asked whether I am glad I kept that secret, my answer is always immediate and sure. I am glad I kept quiet—not because deception is a virtue, but because privacy can be a shelter. There are moments when the world is at its loudest, when expectations creep into grief and we are expected to conform to a role. Edward’s gift of privacy—his deliberate concealment of the house so that I could step into it—was the most essential kindness: a place where I could grieve, remember, and finally decide without pressure.

Years have passed since that first flight. The villa in Marbella still stands with its blue shutters, its lemon trees and its tiny terrace that faces a sea that does not care about family feuds and therefore heals better than town gossip. Catherine and I run a small residency—friends come to write or paint, spend a night under the lemon trees, and then return to their lives. I teach a class when I find the energy. My memoir was published by a small press; people send me letters about how something in the book made them dare to speak. I have friends. A few lovers, perhaps more gentle than anything I had expected. There are quiet dances on the terrace with friends under lights. It is a life that holds more of me in it.

And the children? They have their own lives. They visit; they call. We have taught each other boundaries. We have hurt and been hurt. We have repaired in small ways. They know now that a mother is not a ledger and that grief is not an invitation to become a property manager of another person’s heart. They learned, as I did, that the measure of a life is not how tightly it is organized on paper, but how freely it is lived in the small hours.

If you are reading this and you are part of a family that thinks of elders as liabilities or assets, please pause. Ask: what is the life this person wants? Is it something you can share in, or something you must let be? If you are older and you feel invisible, remember that privacy is sometimes a sanctuary. It is okay to reserve a small corner of your life where no one is permitted to rearrange your furniture—literal or emotional.

On a clear morning, with citrus blooming and the sea like a silver sheet, I stand on my terrace and breathe in the scent of lemon and sun. I am wearing nothing flashy, probably a sweater with a hint of pilling, and my fingers are bare except for the ring Edward liked. I watch Catherine pick basil with nimble fingers and feel a kind of gratitude that is calm and steady. I kept quiet about that house because it was not a secret from me; it was a gift to me. I kept my heart guarded enough to receive it. I am glad I did.

There is, at the very end of all the long and complicated human things we go through—loss, resentment, reclamation—a simple and luminous truth: to live the rest of your life on terms you choose is not selfish. It is an act of self-respect. It is an act that teaches your children that people are not conveniences. And sometimes, when the world wants you to shrink, you do the quiet thing: you accept an unexpected kindness and you build, slowly and stubbornly, a life that is yours.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Fiancé’s Rich Parents Rejected Me At Dinner — Until My Father Arrived… CH2

My Fiancé’s Rich Parents Rejected Me At Dinner — Until My Father Arrived… Part One The grandfather clock in…

My Backstabbing CEO Stole My $4 Billion AI — Until It Mysteriously Started Exposing His Secret Plan. CH2

My Backstabbing CEO Stole My $4 Billion AI — Until It Mysteriously Started Exposing His Secret Plan Part One…

My Stepfather Called Me a Maid in My Own Home — So I Made Him Greet Me Every Morning at the Office. CH2

My Stepfather Called Me a Maid in My Own Home — So I Made Him Greet Me Every Morning at…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Slapped Me In The Face Just Because The Soup Had No Salt. CH2

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Slapped Me In The Face Just Because The Soup Had No Salt Part…

At Christmas Dinner, My SIL Laughed “Your Gifts Are Always Cheap And Useless” – Until He Opened the present I gave him. CH2

During Christmas dinner, my ungrateful son-in-law mocked me, saying, “Your gifts are always cheap and useless.” The whole room went…

On My Birthday My Husband And Kids Handed Me Divorce Papers And Took The Mansion Business And Wealth. CH2

On My Birthday My Husband And Kids Handed Me Divorce Papers And Took The Mansion, Business, and Wealth Part…

End of content

No more pages to load