On Our 20th Anniversary Dinner, My Husband Said, “You’re Just a Housewife—I Want to Live Again!”…

Part 1

I was lighting the last candle on the dining table when Ethan called out from the hallway, “Mom, do you want me to chill the champagne now?”

“Not yet, sweetheart,” I said, smoothing the white cloth for the third time. “Let’s wait until Dad gets here.” The ironed hem wouldn’t lie perfectly flat, and the wrinkle annoyed me more than it should have. Roast duck and cinnamon apples perfumed the house—Mark’s favorite, by his request. A string of fairy lights looped along the sideboard where the crystal flutes caught and tossed back little rings of light. Our framed wedding photograph leaned near the centerpiece as if listening in: two kids outside a chapel in Montclair, laughing against the wind, certain that love was a weatherproof coat.

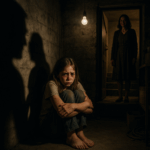

When you’ve known a man for twenty years, you can hear the shape of his absence. By seven-thirty, it was loud. By eight, voicemails stacked—my voice growing smaller, the dial tone growing bigger. By nine, the duck had cooled and hardened. The grandfather clock ticked the way trains do when you have missed yours: indifferent, on time for itself.

“Mom, can we just eat without him?” Sophie asked, arms crossed, hair twisted into a messy bun that was its own kind of crown, the toffee-colored ringlets she inherited from me escaping as if to say we will not be contained by niceness.

“He said he’d be here,” I lied, or maybe just wished out loud.

Ethan poured a little champagne and handed me a ridiculous toast in an earnest voice. “To you,” he said softly. “To the best woman I know.” Sophie rolled her eyes and clinked anyway, and we ate cold duck and warm memories and called it dinner.

At midnight, Sophie kissed my cheek and went to bed, muttering “Happy anniversary” into the air like a prayer. Ethan stayed and washed dishes he shouldn’t have had to wash, humming the way he always hummed when he wanted to stitch the edges of a silence together.

It was nearly three when the lock turned. I’d fallen asleep on the sofa in the cream lace dress I had worn to my sister’s wedding twelve years earlier. Mark came in with the curated carelessness of a man who has decided his choices are the weather and you are a woman without an umbrella.

“You’re still awake?” he said, annoyed, as if I had left the bathroom light on.

“It’s our anniversary,” I said, standing; my knees complained. “We waited.”

He set his coat down with deliberate gentleness, which is how angry men perform being calm. “We need to talk.”

Some sentences announce a life in half. He said the rest with the bored tone of someone reading a voicemail he’d already transcribed. “I think we should separate. I’m moving out tomorrow. You can keep the house, but I’m taking the savings, the car, and the lake cottage. I’ve spent my whole life working for this family. I want to live for myself now.”

My body did the slow wobble furniture does when you cut a hidden screw. I put a hand on the edge of the console table to steady the room. “What happened to you?” I asked quietly. Which is to say: why am I finding out about our divorce at three in the morning while an apple reduction congeals in the kitchen?

“Nothing happened to me,” he said, snapping, as people do when the script doesn’t include introspection. “It’s you. You used to sparkle. You were curious, exciting. Now you’re just a housewife. Always tired, always in that bathrobe.”

“Who is she?” I asked, too tired for pretense. His fingers, drumming. A flush along the throat.

“She’s not the issue.”

“How much younger?”

“Eighteen,” he said, meeting my eyes and daring me to blink.

“Tiffany,” I said. “Does she have a last name or did you buy her one at the boutique where you bought that bracelet?” I had not meant to say it. Three nights earlier, there’d been a receipt in the dryer lint trap, flat and betrayed: Whitaker & Co. Jewelers / Diamond Tennis Bracelet. Mark Whitaker. I picked it up like a live wire and didn’t scream only because no one would have heard me over the tumble dry.

His mouth tightened into something that might once have been a smile. “She makes me feel alive again.”

The next noise belonged to Ethan’s feet. He walked in, hair rumpled, eyes storm. “You’re leaving Mom on your wedding anniversary?”

“Stay out of this.”

“I’m already a man,” Ethan said, and I recognized in him a posture I had not seen since the day he told a boy twice his size to stop taking Sophie’s pencils. “And if being a man means acting like you, I’ll pass.”

Mark does not like being told no. He slammed the counter with his palm. A glass toppled, shattered—shards skittering under the fridge. “I’ll send someone for my things,” he said. “Tell your sister if she wants to stay at that expensive art school, she better stop taking after you.”

“Mark,” I called as he opened the door. This is the part where I gave him one last chance to turn into the man holding a bouquet at our first apartment. “What about your children?”

“They’re old enough,” he said over his shoulder. “Don’t make me the villain.”

He slammed the door hard enough to dislodge the porcelain figurine from our tenth anniversary. It broke into three neat pieces. I left it on the floor. Not because I didn’t love it; because I was too busy not collapsing.

Sophie appeared in the hall, mascara ghosts under her eyes. “He left us,” she said—not a question.

Ethan put his arm around me, around her, and we stood there, three people in a doorway, chewing the bitter rind of a life that suddenly didn’t fit our teeth. Somewhere under the rubble, a single coal glowed. Not hope; not yet. A question: What now?

The next mornings were watercolor—colors bleeding into one another: gray into gray into gray. I slept in my robe. Tea cooled at my elbow and grew a skin. Ethan made pancakes for his sister and ate his in the hall. Sophie floated between rooms like a moth in a museum. On the fifth day, the doorbell rang with righteous insistence, and then a voice: “Grace Elizabeth Whitaker, if you don’t open this door, I will call the fire department and have them kick it down.”

Clare. My best friend since a January day in college when we shared a dryer and a pack of Pop-Tarts. She came in like thunder. She yanked the curtains open and pried the dishes out of the sink’s sulk. “Get up,” she commanded. “You don’t get to rot. Not on my watch.”

“I don’t want—”

“Visitors,” she snapped. “You don’t have visitors. You have infantry. Shower. Clothes. Shoes. Now.”

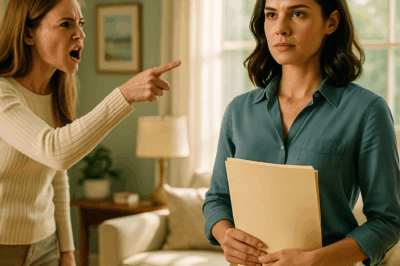

Clare assembled me the way good friends build an ark. After soup and a shower, she stood by the window with arms crossed like she was trying not to break her own heart. “I did digging,” she said. “He’s been planning this.”

“Planning what?”

“The erasure,” she said. “Shell company in Delaware. Quiet transfers. The lake house deeded to a Carl Saunders—Tiffany’s father, I think. He didn’t just leave you, Grace. He tried to make it as if you had never existed.”

My stomach did that elevator drop thing. “How do you even know this?”

“I own a development firm,” she said dryly. “People talk. Also, I paid three paralegals in espresso and gossip.” She glanced at the clock. “Get dressed. There’s a lawyer waiting.”

Daniel Miller had a precise face. He listened like a safe. When I finished telling him the story, he steepled his fingers in front of his mouth and said, “We can work with this.”

“I have nothing,” I said. “No income. No savings. He emptied the accounts.”

“Which is why he moved fast,” Daniel said. “Control is a choreography. But twenty years of marriage is not a toy, Ms. Whitaker. The court doesn’t let a man put his wife in a bag and shake her until she disappears. We’ll file to freeze assets. We’ll trace the rest. And you—” he leveled his gaze at me “—need to find income, because groceries are still rude like that.”

Income. At night, I stood in front of the closet where I had hung version after version of myself, none of which fit anymore. On the shelf above, a bulky hard case hid behind winter blankets. I pulled it down and opened it to find my old sewing machine—a rectangle of memory with a scratched spool pin. Next to it, a sketchbook. Fabric swatches like garden squares. Lines as eager as a first love. Ashes & Thread scribbled on the cover, a phrase that meant nothing then and everything now.

Tucked into the back flap was a photograph: me at twenty, hair in a loose knot, grin like a seam about to break, and Julian West—my school friend—scribbling a note on the back. To the best designer I know, he’d written. My doors are always open. He’d become that Julian—glass-walled atelier on Madison, six boutiques, letters after his name for awards.

He wouldn’t remember me.

The next day he did.

Julian hugged me in the lobby as if no years had passed and none had been wasted. His suit was immaculate. His smile wasn’t.

“You look like Grace,” he said. “That’s a compliment.”

“I need work,” I said. Which is to say: I need to feel real again.

He nodded once. “I need hands. The studio uptown does three dozen custom fittings a week and my tailoring lead has pneumonia. Can you still sew?”

“It’s been years.”

“It’s like riding a bike,” he said, and then, because he remembered me, “One you designed.”

My first hem was crooked. My third was passable. By the end of the week, muscle memory had risen from the dead like Lazarus and asked for a thimble. The sound of a machine is a kind of prayer if you lean into it. Spool. Thread. Press the foot. The needle goes down. Fabric moves away in a straight line you make yourself. There is a kind of power in that: that your hands take a mess and make it into something that holds.

“It’s still there,” Julian said, leaning over my shoulder on day nine as I cleanly turned a collar using a trick we learned from a professor who smoked too much and told us to treat silk like a secret. “I knew it would be.”

Part 2

At home, the legal war bloomed paperwork like dandelions. Daniel called and said words like emergency petition and ex parte and forensic accountant and when I asked if that last one meant a man in a lab coat with a calculator, he made a noise that might have been a laugh. We were going to freeze whatever Mark hadn’t yet hidden and make a map to the rest. But we needed more.

Fate is messy, but it has a sense of timing. Two weeks after Julian put me on the schedule, I got a text from an unknown number: We need to talk. It’s Tiffany. Please. Everything in me stiffened. Clare read the screen over my shoulder and said, “Of course it is.”

We met at a café in Hoboken because Clare insisted Manhattan was her turf and she wouldn’t give it that satisfaction. Tiffany wore careful makeup and an unfortunate blouse. She looked like the ghost of a person who thought she was the heroine in someone else’s movie.

“I’m pregnant,” she said. Her mouth wobbled. “He says I’m lying.”

“What do you want from me?” I asked. I didn’t mean the words to be cruel. I meant: what could possibly make this a conversation instead of the end of one?

She pulled a flash drive from her purse and set it on the table like a talisman. “He left his laptop open. I copied what I could. Bank transfers. Contracts. I don’t understand any of it. I thought—” she swallowed “—I thought you could use it.”

“Why give it to me?”

“Because I see it now,” she whispered. “He did to you what he’s doing to me. I won’t let him do it to my child.”

I took the flash drive to Daniel like a pilgrim. He plugged it in, and I watched his eyes go soft with greed the way a doctor’s eyes go soft when they realize they can save someone. “This changes everything,” he breathed.

We froze accounts that didn’t want to be frozen. We filed for discovery. We found the line from the shell company in Delaware to the lake house to Carl Saunders to a paper crossing in the Caymans that spelled this is what men do when they do not like sharing their toys. In court, the judge wore her silver hair like a crown and peered at the evidence with that expression women over fifty wear when someone underestimates their math.

Mark showed up in a navy suit and a face that looked like he was chewing a vitamin he couldn’t swallow. For the first time, I saw something besides contempt in his expression. Not remorse. That would have been too clean. Fear. He settled before the judge had to growl twice. I took half of a pie I had baked and a slice of a pie I hadn’t known existed. I took the debt off my name. I took the house for real this time. Then I took a shower so long I emerged a raisin and felt myself unfurl.

Meanwhile, in a small studio under a skylight, I made a dress.

Then ten more.

I called the collection Ashes and Thread because that is what was left and what I had. The first look walked the runway like a bruise: high collar, narrow sleeves, cloth that kept secrets. By the middle, a sleeve split open, a lining flashed red like a dare. The last look moved like forgiveness. White without being fragile, sequins at the hem because joy should make noise.

When I stepped out behind the final model, I felt the skin between my shoulder blades light up the way it used to when Mark would stand behind me and say “You’re breathtaking.” But this time the voice came from inside my own body, and it said: Look what you did.

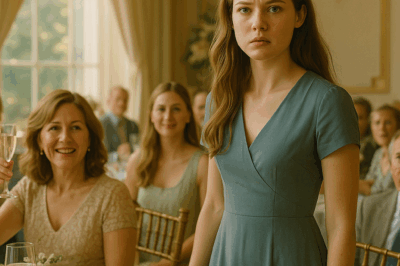

Ethan and Sophie were in the front row, their faces splotchy with a pride that made them ten again, holding fingerpainted mothers’ day cards. Julian had that look he gets when his football team scores in stoppage time. Somewhere near the back, Mark sat alone, clapping because the room told him to. Afterwards he came up, asked if we could talk, tried to fit his “we made mistakes” speech into a thimble. I told him he had helped me become someone I liked. He looked confused. “We’re done,” I said.

“Do I get a second chance?” he asked.

“Not as a husband,” I said. I didn’t say: I don’t want to spend the next twenty years reminding you I exist.

Julian found me on the patio later, coat around my shoulders. “You okay?” he asked.

“I’m full,” I said, thinking of roast duck and long nights and how a seam sits just so when you’ve done it properly.

“Good,” he said. “Let’s do it again.”

“Again?” I laughed. “A sequel to my resurrection?”

“Why not?” He tilted his head. “You’re not done rising.”

I looked at him, really looked. Men who know how to hem trousers don’t often know how to be gentle with hearts. He did. And for once, I stopped treating noticing as the same genre as betrayal.

In the months after the show, the atelier put my name on a tiny brass plate outside a glass door. Grace Whitaker, Creative Director. Sophie interned and caught the color on the wind. Ethan brought Naomi home for dinner on Wednesdays. They asked me to design her dress and I said yes, and in the back of my mind the nineteen-year-old girl who’d given up a scholarship whispered finally.

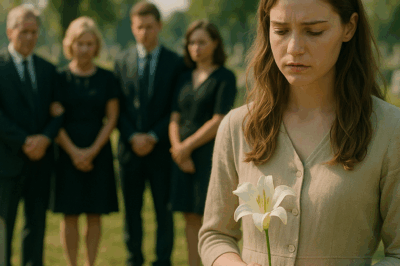

On the morning of Ethan’s wedding, I zipped Naomi into silk and she turned toward the mirror and I saw us both. See? the girl whispered. All that drawing mattered. When they put rings on each other’s fingers in a garden full of August and hydrangeas, I cried the good way. Mark came alone and stayed on the edges and left early, and that was its own version of healthy.

Later, on the dance floor, after Julian spun me in a circle small enough to laugh in, Clare leaned in and asked, “Are you happy?”

“I am,” I said, and then, because I have learned that joy does not like being left unsupervised, I added, “And if I forget, remind me.”

Tiffany sent me a photograph from a delivery room—no text, just a baby with a damp tuft of hair and the exact stubborn mouth as the man who had stolen my twenties. She didn’t ask for anything. I sent back a prayer hand emoji and the number of a lawyer who doesn’t mind working in the half-light where mercy meets law.

When the divorce decree arrived in the mail with its embossed seal and silly weight, I held it and thought of the anniversary figurine in three pieces under the console table. I had never glued it back together. I swept it up after a week and tipped it into the trash. Not because I hated that era. Because not everything broken needs to be made whole again. Some things deserve to rest.

The day after Ethan’s wedding, I opened the atelier’s glass door and stood in the sunlight for a minute before stepping inside. The interns looked up and chorused “Good morning, Ms. Whitaker,” the way a sewing machine hums when ready. On the desk lay a manila envelope from the Emerging Voices competition—yes, I had entered, because being fifty makes you reckless in precisely the right way. Winner, it said. Prize money, a mentorship for a designer underrepresented in the industry. I sat down and cried into my hands because sometimes the good thing sneaks in past your vigilance and sits on your shoulder like a bird.

“Part two,” Julian said, appearing with coffee. “I told you.”

“Stop being right all the time,” I said, and he grinned.

At home that night, I took out the cream lace dress I had worn the night Mark left and held it up to the window. The light came through the pattern the way forgiveness does: in pieces, at odd angles, softer than you expect. I put it away and thumbed through my new collection sketches: brighter fabrics, bolder shoulders, pockets big enough for the women wearing them to put their hands in and feel the weight of their own competence.

I walked out onto the patio and phoned Clare. “Do you remember the name tag?”

“Don’t make me drive over there,” she said.

“I threw it away in the church park,” I said. “But sometimes I think about pinning on a new one.”

“What would it say?”

I thought about it. About labels, about tape residue, about how long it takes for adhesive to let go. About my children’s hands in mine. About a girl in a photograph in a studio in Madison. About my name on a brass plate. About the smell of cinnamon apples.

“It would say ‘Grace,’” I said. “And that would be enough.”

“Finally,” Clare said, and I could hear her smile.

“Finally,” I agreed.

And I went to bed not a wife, not an ex-wife, not a scolded bank account, not a ghost in a robe, but what I had been all along and was learning to trust: a woman with a needle and a steady hand, stitching a life that fits.

END!

News

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

At My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. CH2

My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. Part One…

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a… CH2

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a … Part…

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration. CH2

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load