Part I:

The shower was still running when I opened my laptop. Steam slicked the mirror, turned the bathroom into a fogged courtroom where the defendant hadn’t arrived yet but the case was already won. I’d spent a decade in corporate law learning to find the line between legal and lethal. It was somewhere in the numbers—always in the numbers. My fingers hovered over the keyboard like a gavel over polished wood, and a plan began to take shape with the clean certainty of statute.

Griffin had been careless, and carelessness is the faint perfume of guilt. He’d come home late, smelling like bergamot and something darker, a fragrance with edges. There were receipts in the shared email I was never supposed to check, charges on the business AmEx with “client dinner” typed so often it felt like he was covering his eyes with his own hands. The Uchi charges were the ones that kept stuttering the cursor in my head: Thursdays, almost always eight o’clock, the ritual of a man who wanted his betrayal to have a calendar. I looked up Uchi’s private dining page and scrolled through room options—Nashi, Sakura, Koi—each one pristine and discreet. A hush you could rent by the hour.

If he wanted to play games with my marriage, my money, my future, he’d ignored a crucial detail about the woman he married: I didn’t just practice law. I tried cases designed to leave powerful men shivering in glass towers they thought would never crack. I didn’t just know the rules; I knew which rules would cut when I pulled them taut.

I dressed for the office like I always did: navy dress, the pearl earrings my grandmother had pressed into my palm on my first day at Morrison & Associates, and the red lipstick I saved for closing arguments. By the time I slid into my chair downtown, the adrenaline had cooled into the clean, hard calm of preparation.

“Emerson, you look like death in a blazer,” Jessica said without looking up. She’d been my paralegal for two years, a quiet hurricane in sensible shoes and a messy bun too defiant to ever fall.

“I need a comprehensive on someone,” I said, dropping the printed statements on her desk. “Financials, property, liens, business filings, the works. Every shadow that can be made to talk.”

She skimmed the pages, and her eyebrows rose like a curtain. “Holy hell, M. Is this what I think it is?”

“It is,” I said. The words tasted metallic. “Four months’ worth. Palmer Architecture LLC is the vendor. She’s married.” I let that land. “To a deployed staff sergeant.”

Jessica’s mouth tightened into the line I’d seen when she read stories about dogs abandoned on highways. “Name?”

“Monroe. Monroe Elizabeth Palmer.”

“Got it.” She was already typing, her fingers a metronome of focus. “Do we call the divorce sharks or are we going full Chernobyl?”

“We’re going nuclear,” I said. “Carefully. Legally. Maximum yield without fallout on me.”

She glanced up, meeting my eyes, and nodded once. “Roger that.”

Two hours later, a dossier landed on my desk thick enough to crush crickets. Palmer Architecture: two employees plus a registrar-listed intern. Behind on rent, three months late on equipment financing, an unanswered demand letter threatening litigation for project delays. Personal credit cards leaned over like trees in a windstorm: restaurants, boutiques, a pattern of small charges that grew like a tide. Jessica had color-coded it so the escalation screamed across the page.

“Classic extraction,” Jessica said, tapping the timeline with her pen. “Start small, build trust, test limits, scale. She found a target with access to cash and the ego to think he was doing the rescuing.”

I stared at the red blocks that marked the Thursdays. They matched the Uchi charges, like constellations named for something I’d rather not know. My phone buzzed—Griffin, of course: Working late tonight, honey, don’t wait up. Love you. The audacity made my hand itch to throw the phone out the window. Instead, I placed it face down on the desk, picked up the office line, and called Uchi.

“This is Emerson Carter,” I said when the hostess answered. My voice found that courtroom lilt that made jurors lean forward without knowing why. “I’d like to reserve a private dining room for six on Thursday at seven-thirty.”

“Any special occasion?” she asked, light, cheerful, professional.

“A business meeting,” I said. “The kind that changes everything.”

When I hung up, I made three more calls.

First: Richard Carter, Griffin’s father. Old money Texan, refinery-grade pride. Primary investor in our company. He picked up on the second ring and called me sweetheart like he’d always done. “Dinner Thursday?” I said. “Big architectural partnership Griffin’s been cultivating. I want your input.”

“Wouldn’t miss it,” he said. “Patricia’s been itching to meet the brains.”

Second: Judge David Palmer, thirty years on the bench, the kind of man for whom family was a solemn noun. I’d stood in his courtroom twice and won once, and he’d shaken my hand both times with the same direct grip. “Judge Palmer, this is Emerson Carter—Morrison & Associates. I’m calling about your daughter Monroe. My husband’s tech company is entering a potential partnership with her firm. Would you and your wife be available Thursday for dinner? I’d value your perspective.”

He paused like a gavel held in air. “Monroe hasn’t mentioned any such partnership,” he said finally. “But Helen and I would be honored to hear about our daughter’s ventures.”

Third: the base liaison office listed for Staff Sergeant Marcus Palmer’s unit. Legal credentials are keys if you know which locks are worth trying. I learned what I needed to know: early return in three weeks, a surprise homecoming. Surprise homecoming indeed.

Griffin came home that night at midnight with the scent I’d come to think of as purchased intimacy clinging to his collar. He carried a white paper bag like a child hiding a broken glass ornament behind his back. He kissed my forehead and sank onto the couch. “How was your day?” he asked.

“Interesting,” I said, eyes on my screen. “I’m working on something I think will surprise you.”

“You work too hard, M,” he murmured. “You should take time for yourself.”

“I did,” I said. “I made a dinner reservation for Thursday. Private room. A business dinner.”

If you’ve spent enough time watching faces under fluorescent cross-examination, you notice the tiny glitches. The microsecond twitch when someone falls through a trapdoor in their own story. Griffin’s face flickered. “Thursday? I might have to work late.”

“I don’t think that will be a problem,” I said. “Everyone’s eager to meet your business partner.”

Color drained from his face as if someone had pulled a stopper at the base of his neck. I mentally added that shade—overcooked halibut—to a chart of human guilt tones I was building for no one but myself.

He barely slept. I felt him turning, the bedsheets a whispery record of restless thought. At three a.m., he got up. His phone lit his face to the pale of a drowned man. Hands moving, message after message. Damage control sent to a woman who had never learned the sound of legal language walking down a hallway.

Morning came gray, Austin rain needling the windows. Griffin looked wrecked, cupping his coffee like a defendant holds prayer beads. “About tonight,” he said, careful as a thief on creaky stairs. “Maybe we should postpone. I’m not feeling great.”

“Your parents have driven in from Houston,” I said, buttering toast with the precision I saved for drafting settlement agreements. “Judge Palmer cleared his evening. Everyone is very excited to meet your partner.”

He flinched at partner. In the courtroom of breakfast, that was my first sustained objection.

He left the house twenty minutes later, hurrying in a way he never hurried unless he was late to the truth. As soon as his Tesla taillights disappeared, I called Jessica. “Phase two,” I said. “How’s the documentation?”

“It’s Christmas morning for a divorce attorney,” she said, voice bright and lethal. “Bank statements. Hotel receipts you didn’t know about. And the gift: Griffin opened a business credit card Monroe’s been using to furnish a downtown apartment. Fifteen grand of West Elm and Pottery Barn. Lease in the company’s LLC with a buyout clause at six months.”

My lungs forgot how to be lungs for one second. “He bought her an apartment,” I said. The words didn’t sound like words. They sounded like a water main rupturing under an old street. “With my money and my signature.”

“There’s a Tiffany run,” Jessica continued, unflinching. “Eight thousand. Thursdays. A cadence. Your reservation’s at seven-thirty, right? He has a standing one at eight. The hostess confirmed it for, uh, ‘Mr. Carter.’ She used the voice you use for repeat customers who tip and don’t throw up.”

I exhaled. “I need the package printed, tabbed, and ready to read without a law degree.”

“You got it.” She hesitated. “M… are you sure you want to do this publicly?”

I pictured Monroe in her red dress, walking into a room she thought would be candlelight and salmon belly nigiri and a married man tilting toward her like a compass needle. I pictured Richard and Patricia Carter, beautiful and satisfied in the way of people who have never been told no by anyone they couldn’t buy. I pictured Judge and Mrs. Palmer, good people who’d built their lives on the idea that vows were bricks, not balloons.

“I am,” I said.

That afternoon, I left the office and did something I hadn’t done for myself in months: I bought a dress that made me feel like my closing-argument self even without a jury. Tailored black. Modest neckline. Pockets. I added the pearls and the red lipstick and looked in the mirror at a woman I recognized and liked.

At five, Griffin called to feign food poisoning. By six-thirty, he’d run out of excuses and I’d run out of patience. At seven, I pulled up in front of his office building and he slid into the passenger seat looking like a man who’d seen the future and didn’t care for it.

“You look nice,” he said, voice small.

“Thank you,” I said. “I want to make a good impression on your business partner.”

He swallowed. The drive to South Lamar took fifteen minutes. It felt like hours packed into a weeping metronome. Griffin kept starting a sentence, then abandoning it like a commit he knew would fail review.

At Uchi, the hostess greeted us by name and led us toward the private room. “Your party is already seated,” she said brightly, and Griffin paled again.

Through the glass, I saw them: Richard and Patricia, elegant and composed, wineglasses in hand; Judge Palmer and his wife Helen, dignified in the way good people wear dignity when they don’t know a storm is forming. The table was set with small plates and chopsticks, each place a stage with a prop.

“Ready to meet your business partner?” I asked Griffin at the door. He said my name in a broken voice, but I’d already pushed it open.

“Everyone,” I said, smiling the way you smile on the first page of a deposition transcript, “thank you so much for coming tonight. Griffin and I are thrilled to introduce you to his architectural consultant. She should be here any minute.”

At 8:03 p.m., right on schedule, the door behind us opened. Monroe Palmer stepped into the private room in a red dress that had learned confidence by rote. She smiled the practiced smile of a woman who knows men turn when she enters a room. She expected one man. She got six of us and a reckoning.

Her eyes found Griffin, then me, then the older faces at the table. The smile faltered. She looked like a sorcerer who’d stepped onstage to find the lights up and the audience full of police officers.

“Monroe,” I said, standing. “Perfect timing. Everyone, this is Ms. Palmer of Palmer Architecture.”

“What is this?” she asked Griffin, voice a half octave off target.

“Please, sit,” I said, pulling out the chair across from Patricia. “We were just discussing the consulting work you’ve been doing for our company.”

“It’s a new partnership,” she said to no one, to everyone, and sat.

I opened my leather portfolio and slid the first tab toward the center of the table. Bank statements, highlights in uncompromising yellow. “As you can see,” I said, “Palmer Architecture has invoiced us fifteen thousand across four months. Generous for a young firm and a struggling startup, wouldn’t you say?”

Richard frowned. “Griffin,” he said softly, a father’s last request for a better story. “This wasn’t in the quarterly reports.”

Griffin opened his mouth and closed it.

“Not the interesting part, though,” I continued. Tab two: business AmEx statements, the black-and-white trail that doesn’t lie. “Here we have jewelry. Furniture. Restaurant charges that look a lot like dates to me. And a downtown apartment leased to our company, furnished to the tune of fifteen thousand.”

Patricia stared at the page as though the numbers would blink and become a different language. Judge Palmer’s face darkened to the color of evening storms.

“Monroe,” he said. “You never mentioned consulting for a tech firm.”

“Daddy, I can explain.”

“We all can,” I said, taking out my phone. “But it’s better if we add a voice who deserves to be here.” I dialed the number the liaison had given me and put the call on speaker.

“Staff Sergeant Palmer,” a man’s voice came crisp and controlled over the table.

“Marcus,” Judge Palmer exclaimed, half-standing. “We’re at dinner with Monroe and—”

“Business associates?” Marcus asked. His voice had the weight of someone who’d carried younger men’s lives on his back and hadn’t dropped any yet. “Sir, I’m calling because I received evidence today of my wife’s activities during my deployment. It seems she has been conducting an affair with a married man named Griffin Carter, financed with his business’s funds while she continued to receive military spouse benefits.”

The silence in the room was ecclesiastical. Beyond the glass, the dining room continued its elegant murmurs. In our private room, oxygen turned into lead.

“Marcus, it’s not what you think,” Monroe whispered, all the polish knocked out of her voice.

“It’s exactly what I think,” he said. “I have bank statements. Photographs. Four months of what any reasonable person would call financial infidelity.”

“Griffin,” Richard said, the word a sound a man makes when a plane wing snaps in turbulence. “Tell me this isn’t true.”

I slid the final folder onto the table. Lease, photos: the red couch, the fig tree leaning toward a window, the borrowed city. “It’s true,” I said. “And I believe Mr. Carter was planning permanence. Buyout clause at six months.”

Patricia’s hand flew to her chest. Helen Palmer stared at her daughter with a sorrow I would remember until the end of my life.

“Monroe Elizabeth Palmer,” the judge said in a voice that had reduced men twice our size to quivering sincerity, “explain yourself.”

“I—” Monroe began, and stopped, and looked at Griffin, who would not meet her eyes.

“Mrs. Carter,” Marcus said over the phone, “thank you for including me. I intend to handle my private family matters when I return to Austin next week. Early. Apparently, the Red Cross expedites flights for family emergencies. Who knew?” The calm in his voice was scarier than rage.

“Marcus,” I said, keeping my gaze on Griffin, “for what it’s worth, I’m sorry you learned this way.”

“Don’t be sorry for telling the truth, ma’am,” he said. “Be sorry for the people who believed they could stash it in a private dining room and call it business.”

Richard closed the folder like a judge closing a book he’d once loved. He looked at his son carefully, as if searching for an exit in the wrong building. “You used investor funds,” he said. “You used your wife’s labor and my money to finance an affair.”

Griffin’s mouth finally produced sound. “Dad, I—”

“We’ll be in touch,” Richard said, and with that, the decades-old scaffolding supporting Griffin’s self-esteem collapsed, quietly, like good architecture failing anyway.

“I think this business meeting is concluded,” I said, standing. My hands didn’t shake. I thought they would. They didn’t.

When I walked out, I didn’t look back.

That night I slept for the first time in months. Not the fluttering nap of a woman who pretends she doesn’t know. Real sleep, the kind you earn by telling the truth so loudly it won’t stop echoing even if you want it to.

In the morning, Austin was scrubbed clean by rain and light. I made coffee. I watched the steam rise. I waited for the second round of explosions to roll through my life. They did.

They always do.

Part II:

There is a strange quiet that follows the detonation of a life. Everyone moves slower around you, like the air thickened and you’re the only one who can breathe it. The morning after Uchi, I walked into the office with a bag of breakfast tacos and a plan stitched to my spine.

“Report?” I asked, sliding a foil-wrapped potato-egg-cheese onto Jessica’s keyboard.

“Nothing screams obstruction yet,” she said. “But the Carter elders are already assembling a battalion. I got three voicemails from Richard’s counsel asking for ‘clarity regarding certain allegations.’ Translation: They want to know whether they can salvage the brand by reshuffling a guilty son into a quiet corner.”

“Can they?” I asked, purely as sport.

“If you were an investor?” She shrugged. “Depends on how this plays when it crawls out of private rooms into the sunlight. I took the liberty of forwarding them our documentation.” She paused. “You okay that I did that?”

“Yes,” I said, and meant it. “Richard deserves the truth as much as anyone. He’ll handle the money. I’ll handle me.”

“And Griffin?” she asked.

“I’ll handle him too.”

By noon, consequences were returning calls like sales reps on commission. Patricia sent a message that was as kind as anyone can be when their brain is rebuilding the castle and reassigning the traitors to the moat. We love you. We’re stunned. We’re on your side, sweetheart. Richard was less padded. Meet with counsel today. No more company assets touch Mr. Carter’s hands without two signatures not belonging to him.

Griffin sent twelve texts that oscillated from apology to anger to the performative ghost of therapy-speak—I know I violated your trust but we need to process this as a team—and back to apology. I did not respond. I had demanded honesty. He had delivered evidence. The rest was math.

Afternoon brought a meeting with my firm’s managing partner, a woman named Loretta who wore her hair in uncompromising coils and her competence like cartilage. “I hear you pulled a sword out of a sashimi roll last night,” she said as I closed her office door.

“Something like that,” I said. I set the folder of evidence on her desk because there are moments when having your mentor witness your life matters more than winning a motion. “I’m not here for drama. I’m here because I suspect I’ll need to step back from the Anderson class-action and the Parker arbitration while I take apart my marriage with surgical gloves.”

Loretta flipped through the tabs. She exhaled once, softly. “Do you want to stay, Emerson?”

“Yes.” The truth surprised me with its firmness. “But not as the woman whose husband humiliated her in a private dining room. I want to stay as the attorney who knows where every dollar hid and why.”

“You have my full support,” she said. “And my rage. Take the time you need. Use the investigators. We’ll reassign the cases for two weeks. After that, you tell me if you want back in or out. And if you decide to build a practice around this—” she tapped the statements—“I’ll back you.”

I didn’t cry. I wanted to. I didn’t.

When I returned to my office, Jessica had a gift waiting: a printed packet titled “Prelitigation Asset Protection Strategies: Carter v. Carter.” It was our firm’s standard checklist for spouses of financial adulterers. I’d given it to dozens of clients. I’d never understood its comfort until I saw my name in twelve-point Garamond under the header.

“Also,” Jessica said, “Judge Palmer requested a meeting. Today. Alone.”

“Of course,” I said, pulse hitching. I braced for rage. I’d be angry too if a stranger put my family on speaker during the worst night of our lives. “Time and place?”

“His chambers, five o’clock.” She lifted her chin. “Want me to come?”

“I should go alone,” I said. “You take first pass on filing the temporary restraining orders on joint accounts. I’ll sign after the judge.”

She smiled ferally. “With pleasure.”

I expected the courthouse to smell like old arguments. It smelled like fresh linen and the lemon polish the custodians used on the benches. The bailiff ushered me into chambers with a neutral nod, and Judge Palmer stood from behind his desk like a hurricane rising from warm water.

“Helen,” he said gently to his wife, who sat near the window, hands folded, face pale but steady. “This is Ms. Carter.” Then, to me: “Emerson. Thank you for coming. Sit.”

I sat. The judge remained standing. He seems like a man who only sits when the world is in order. “I received your message this morning with the documents,” he said. His voice was even, but the air around it felt charged. “And I want to begin by saying: I am grateful you told my son the truth last night. I don’t know if that’s the way I would have chosen, but I didn’t choose. You did. It spared him from finding out in an airport lobby with a Wes Anderson soundtrack and a coffee he would have thrown against a wall.”

Helen’s eyes filled, and I fought the electric urge to cross the room and kneel at her feet like penance. Instead, I held her gaze and nodded once, my throat thick. “I’m sorry for the pain,” I said. “And I’m not sorry for the truth.”

“Good,” the judge said, as if I had passed an exam I didn’t know I was taking. “I have two questions. First: Do you intend to press criminal charges related to misuse of corporate funds?”

“I intend to let the facts fall against the statutes,” I said. “If the DA decides they amount to criminal conduct, I won’t stand in the way. But my priority is civil: securing my financial future, removing Griffin from any access to accounts, and reclaiming the company I co-built.”

“Second,” he said, leaning forward, “do you intend to pursue my daughter professionally? I’m not asking for her sake. I’m asking for the shape of the future.”

I met his gaze. “If there are civil avenues to hold her accountable for her role in extracting business funds under false pretenses, I’ll pursue them. I don’t care if the record calls it fraud, unjust enrichment, or a very expensive education. I’m not interested in revenge. I’m interested in prevention.”

Helen spoke for the first time, her voice a careful instrument. “Prevention?” she asked.

“For the next woman,” I said, the certainty surprising me again with its fullness. “For the woman who doesn’t have a law degree or a paralegal who knows which drawers hide the truth. For the woman whose red flags still look like bunting she’s been told to enjoy.”

Helen looked at me as if assessing a bridge for weight capacity. After a long moment, she nodded. “Then you do what you need to do,” she said. “David and I will handle our daughter.”

I left the courthouse with a stapled packet bearing a judge’s signature: temporary restraints, emergency orders, a neat set of guardrails for the cliffside road my life had decided to take. Outside, the rain had paused to breathe. The sky over the Travis County skyline was the washed blue of a clean page.

Griffin called as I crossed the plaza. I answered because some doors you close with a slam and others with a click you can hear across a room.

“I’m sorry,” he said immediately, which was almost funny. The apology arrived like a pizza forty minutes late and slightly cold but technically edible.

“For what?” I asked.

“For everything,” he said. “For getting caught.”

“You see the problem,” I said, and he went quiet, because sometimes I forget he once had a spine that wasn’t borrowed. “This wasn’t an accident of desire, Griffin. It was theft. From me. From the company. From your parents’ investment. From a man wearing sand in his boots so you could eat miso black cod with a woman in a dress that matched your lies.”

“You don’t understand,” he said, finding anger the way a man grabs for an oar in water he made deep himself. “I was under pressure. The company—”

“The company you accessed like an ATM,” I said. “The company I ran while you played founder on LinkedIn. We’re done. Legally, emotionally, financially, anatomically. My lawyers will communicate with whatever counsel you retain.”

“I thought we could… talk,” he said, small again. “Work through it.”

“You thought wrong.” I ended the call.

Back at the office, Jessica had the world ready for my initials. I signed motions, letters to banks, notifications to vendors. We scheduled a board meeting with the company’s two remaining directors—Richard and me—at ten the next morning. Agenda item one: removal of Griffin Carter as CEO, pending cause. Agenda item two: appointment of interim CEO. If the voice in my head was smug when it said my name fit nicely on that line, I let it be smug. It had earned the indulgence.

That night, alone in the house Griffin would soon vacate, I walked room to room and took inventory. Not of furniture—the lawyers would parse that—but of quiet. The living room had been a place for his laughter. Was it different without it? The kitchen held memories of pasta, the kind made together under the lie of teamwork. Those would go too. My office was safe; that room had always been mine, strewn with binders and the smell of toner and the single plant I’d managed not to kill.

At my desk, I wrote the first draft of the rest of my life. The new practice would specialize in what Jessica had named without flinching: financial infidelity. We would create a pipeline for women who needed power before they knew where to ask for it. Forensic accountants on retainer. Private investigators who knew how to be unseen. Digital security experts who could trace a paper trail through hell and back and print it on letterhead.

I called Loretta and pitched it as if she were a tightfisted VC in a bad mood. She wasn’t. She loved the idea instantly. “Call it what it is,” she said. “People don’t want euphemisms when they’re bleeding.”

“Financial Infidelity Practice Group,” I said. The words clicked into place with the inevitability of precedent. “We’ll build templates, trainings, a hotline—not a charity, a firm. We’ll get rich making sure rich men can’t hide what they buy for fun with cash they owe their families.”

“Send me the plan tomorrow,” she said. “And Emerson?”

“Yes?”

“Win,” she said.

I slept. Again.

By the end of the week, the company had a new CEO—me—and a new mission statement—not fraudulent. Griffin was served with papers at his co-working space, and something about the image made me smile into my coffee with a mean satisfaction that didn’t bother me at all. Richard called to inform me that he and Patricia were withdrawing all personal support from their son.

“We won’t cover his legal fees,” he said. “We won’t house him. We won’t launder his reputation with announcements about ‘personal growth.’ He does not get to lick this clean.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it. I had loved Griffin once. I still liked his parents despite everything. They didn’t deserve to learn what their son looked like in emergency lighting.

“We are too,” Richard said. “We’re also grateful to you. You saved our investment. If you want to buy us out when the dust settles, we’ll talk at a fair valuation. Until then, run what you own.”

“I intend to,” I said.

I met with Monroe’s soon-to-be-former landlord, who turned out to be a practical woman with a neon pen and no patience for romance at market rates. She’d seen the photos Jessica took—she didn’t ask how we got them—and agreed to terminate the lease in exchange for a three-month penalty paid by any party whose name appeared on the paperwork. That meant the company. That meant me, technically. I paid it anyway with a smile that hurt less than I thought it would. That money felt like the last shipment exported from the country of my trust.

Monroe herself sent nothing. She had gone quiet, which I understood as the silence of someone organizing stories into a defense. But her parents called Jessica to apologize for “the scene at dinner,” as if they’d been the ones to drop a chandelier onto the table. They’d started volunteering with a military family support group, Helen said, because what else do you do when your daughter makes a mockery of a flag other people folded?

I worked, which is to say I built something: a department, a mission, a new spine for my career. Clients arrived with shame pressed into their faces like a brand. We met them with coffee, confidentiality agreements, and a stack of checklists that began with, You are not crazy. Here is the math. We traced Venmo payments labeled “gym membership” through a tangle of shell LLCs to a condo with a rooftop you could see on Google Earth. We subpoenaed hotel loyalty programs. We worked with therapists who didn’t minimize the carnage by saying boys will be boys because boys who become men with corporate cards are not children; they are adults conducting commerce with hearts they did not pay for.

The night before the preliminary hearing to confirm the restraining orders, I opened a new file, slid an unopened letter into the inside pocket, and wrote in neat block print: Carter, G. It wasn’t nostalgia. It was evidence. The letter would stay sealed until the case was closed. If the judge ever asked me what it contained, I would say the truth: a story I no longer needed.

On Friday, I drove to Lady Bird Lake at lunch and walked its edge until the muscles above my knees reminded me I’d been sitting too long for too many weeks. The water was a wash of sky and ducks and people who understood that running is cheaper than therapy and often more effective. On the pedestrian bridge, I leaned against the rail and thought about the woman I had been: good, competent, kind, assuming good faith until the receipts showed me otherwise.

I didn’t hate her. I also didn’t miss her.

I wondered whether Monroe was looking at any water anywhere. I pictured her in a kitchen searching for the mug that used to sit on the right side of the sink and wasn’t there anymore. I pictured her stopping her hand halfway to the drawer where the fancy chopsticks used to be. I pictured her learning a lesson that had cost me fifteen thousand in furniture and four months of Thursdays and the taste of my own mouth when I said business partner like a blade.

Then I went back to work. Because when you’re a woman rebuilding her life, the most radical thing you can do is invoice for your time.

Part III:

The second Thursday after Uchi, I wore the black dress again. Not because I needed armor—though it felt like that too—but because rituals deserve reclamation. Griffin and I met at the courthouse corridor flanked by our attorneys. He looked smaller. Not thinner; diminished. There’s a difference and the eye knows it.

His counsel, a man named Burke whose reputation for conciliatory settlements had always irritated me on principle, nodded at me with the polite pity men offer when they think you have become a public tragedy. My counsel, Loretta herself today, gave him a smile sharp enough to nick silk. “Shall we?” she said, and we filed into the judge’s hearing room like two squads of firefighters who hate each other but still know the choreography.

The hearing was to confirm temporary restraints and set preliminary terms. It wasn’t the day to burn the edif—no, that was wrong. The edifice had already burned. Today was about surveying the lot lines and deciding who got which corner of the ash.

The judge, not Palmer for obvious reasons, was a woman in her fifties with a voice that could soothe a foal and scald a fool as needed. She read the motions, asked the questions, listened to the answers. She looked at Griffin over the half-moon of her glasses. “Do you dispute that company funds were used for personal expenses unrelated to legitimate business needs?”

Griffin swallowed. “I—there were reimbursements. I intended to—”

“Do you dispute,” she repeated, not unkindly and absolutely without interest in his ornaments, “that funds were spent on jewelry, furnishings, restaurants, and rent for a personal apartment?”

He glanced at Burke, who nodded once, a permission slip to stop lying to an adult. “No,” he said.

“Thank you,” she said. To me: “Do you seek exclusive control of business accounts pending a full hearing?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” I said. “And appointment as interim CEO per the corporate bylaws. The board has already voted one to one,” I added, allowing myself the smallest smile. “Mr. Carter does not currently hold a seat.”

She nodded and stamped the page. The sound was softer than I’d expected, a little administrative kiss. Power rarely sounds like thunder. It sounds like competence operating at room temperature.

After, in the hallway, Griffin asked if we could have five minutes alone. Loretta looked at me and I said yes because some ghosts deserve the courtesy of being seen one last time. We stepped into an alcove by a bulletin board papered with flyers for community mediation and a lost scarf.

“You made me look like a monster,” he said. For a second, I saw the version of him I’d once loved, the boyish arrogance that felt like sunlight when it shone on me and like melanoma when it didn’t.

“You made yourself look like a monster,” I said. “I made you look like evidence.”

“You humiliated me,” he murmured, eyes flat. “In front of my parents. In front of a judge.”

“You humiliated yourself,” I said. “In front of a waitress who brought you the check every Thursday.”

“I was going to tell you,” he said, which is the second lie men tell when the first one fails. The first is Nothing is happening. The second is I was just about to tell you. The third is It didn’t mean anything, as if meaninglessness is absolution.

“No,” I said. “You were going to keep both lives until one paid you more.”

He rubbed his face. “What do you want from me?” he asked finally, genuine for the first time in weeks.

“I want you to sign the documents without theatrics,” I said. “I want you to stop calling me at night. I want you to stop believing you are the victim. And I want you to try being a person you wouldn’t cheat on if you met him.”

His laugh startled both of us. It was a little boy’s laugh stuck in a man’s ruined day. “That last one,” he said. “That’s not law.”

“No,” I said. “That’s living.”

We returned to our attorneys, who did what attorneys do: they filed edges off jagged paper and arranged signature blocks like origami. Burke promised dates. Loretta promised subpoenas. I promised myself dinner that would not taste like adrenaline.

That afternoon, Jessica and I finalized the draft for our new practice. We named it The Ledger Group at Morrison & Associates because our marketing director loved a metaphor you could bill against. The site would launch with an article titled “How to Recognize Financial Infidelity Before It Destroys Your Life,” written by me under a pseudonym we collectively agreed was too noir by half and therefore perfect: E.M. Ledger.

Before I could approve the copy, my phone buzzed with a number I recognized now: the base liaison. “Mrs. Carter? Staff Sergeant Palmer has arrived stateside ahead of schedule. He asked me to let you know he will be in Austin by tonight. He requests no further involvement from you.”

“Of course,” I said, heart lurching with a complicated mix of relief and dread and something like hope for a man I didn’t know. “Please tell him I wish him… I wish him well.”

“I will,” the liaison said, and we hung up.

At six, I made soup because soup is the food of people who need to be reminded they can be gentle to themselves. My doorbell rang at seven-thirty. When I opened the door, Marcus stood on my porch in a dress uniform, cap tucked under his arm, profiles of exhaustion carved into his face.

“Mrs. Carter,” he said. “I know I asked for no further involvement. But I needed to tell you in person: thank you.”

“You don’t owe me—” I began.

He shook his head. “I do. You didn’t owe me anything. You could have walked away and left me to learn it bad and alone. You told me the truth. That’s a debt I can carry without hating it.”

I stepped aside, but he shook his head again. “I’m headed to my parents’ house,” he said. “The judge and his wife. I know you know them.”

“I do,” I said. “They’re good people having a bad month.”

He almost smiled. “Isn’t that the whole world right now.” He adjusted his cap. “One more thing. You don’t need my blessing for anything. But if you ever need a witness to the character of a woman who chose justice over embarrassment, you’ve got one. Ma’am.”

He left. I stood in the doorway with the smell of soup and the echo of someone who knew how to say thank you without hating that he had to say it.

The next week was a litany of consequences. Monroe’s professional board received an anonymous ethics complaint supported by public records and notarized statements. The complaint did not mention the word affair; it mentioned misuse of client funds, conflict of interest, and failure to disclose financial relationships that could influence professional judgment. Facts, not flames. The board opened an inquiry. Monroe hired counsel, a woman known for extracting clients from holes they’d dug with gold-plated shovels. Good for her. I want the people across the table from me to be brilliant. Losing is a poor teacher. Winning against someone capable is a doctorate.

Richard filed a derivative suit on behalf of minority shareholders—that was him—to recover misappropriated assets from Griffin. It was a clean pleading. It made what Griffin had done sound dry, which is the worst thing you can do to someone who thought he was the protagonist: convert his melodrama into accounting.

Loretta and I negotiated a private separation agreement that gave me the company, the house, and a significant share of future profits in exchange for letting the public record remain quiet on certain details if Griffin cooperated. It wasn’t a gag order. It was a gentle muzzle on the dog that had bitten too many hands already.

Two Thursdays after Uchi, I returned to the restaurant with Jessica. We sat at the bar, not the private room, and ordered the salmon belly nigiri because I refused to let a menu become a cemetery. “To us,” Jessica said, raising her glass. “To women who turn receipts into weapons.”

“To women who turn weapons into shields,” I said, clinking.

Halfway through the meal, a couple took the corner table by the window. They were laughing the way people do when they don’t know yet. For one second, the sight pierced me with a clean, surprising pain. Then it passed. I wasn’t cynical; I was awake. There’s a difference and the heart knows it.

When we left, the hostess smiled at me in the new way—the way people smile at a woman they’ve read about without knowing where. I smiled back. I had nothing to hide and therefore nothing to manage.

The next morning, we signed the papers. Griffin’s signature shook as if the letters were trying to run away. Mine did not. In the hallway, he asked, “Will you ever forgive me?”

I considered the question like a proposal. “Forgiveness is above my pay grade,” I said. “I can release you from my life. I can wish you well. I can refuse to light a candle to your memory. But I can’t make you into a man I would have married if I’d known you better. That’s between you and the mirror.”

He nodded once, and for the first time since the night at Uchi, his eyes met mine and stayed. Whatever he saw there sent a shiver through him. He turned away. Burke put a hand on his shoulder. Loretta put a hand on my back. We left the building like survivors of the same shipwreck, climbing onto different shores.

Two days later, The Ledger Group launched. The phone began to ring. The inbox filled. The receptionist learned how to say, “I am so sorry. You are not alone. May I have your email to send you our intake forms?” in a way that felt like a blanket and not a bucket.

We hired another attorney, and then a third. We contracted with a forensic accountant named Ed who looked like a substitute teacher and could reconstruct a ten-year asset history from a pile of napkins and one digit of a bank account number. We created a workshop for therapists to spot financial grooming. We did a seminar for bankers about the difference between privacy and prophylaxis. We started winning.

I didn’t keep a tally, but the ribbon of justice fluttered behind us, bright enough to track. Each case closed with a woman who could breathe again and a man who had learned that money leaves footprints even when love has no witness.

On a quiet Friday at dusk, I sat alone in my office and opened the letter I had used as a bookmark. Griffin’s apology read like a man begging a jury to consider his childhood in mitigation. It wasn’t evil. It was ordinary. That was worse. I slid it back into the folder and wrote across the outside in neat blue ink: Closed.

Part IV:

Six months rolled by like thunderheads across the lake: slow, inevitable, occasionally violent, always moving toward a storm and away from one at the same time. The office had grown around me like a city. Twelve attorneys now—six in litigation, three in transactions, three in investigation. We had a weekly meeting where we did not say clients’ names out loud, only case numbers and moral lessons:

Case 117: If he insists on paying contractors in cash pulled from a cigar box, assume he owns a second life with a front lawn.

Case 204: When the Venmo descriptions say “Taxes,” ask whom he’s paying. He is not paying the IRS to a handle called @SunsetBoulevard.

Case 289: Women can be the betrayers too. Prepare without prejudice, prosecute without spite.

Clients brought us stories like blood-stained shirts. We cleaned them. We returned them pressed and documented with chain-of-custody logs.

Every Tuesday afternoon, I took appointments from women we’d flagged as likely to need more than law. We kept tissues in a drawer and water in a pitcher and the understanding that the first thirty minutes were not billable. Empathy is a cost center. It pays dividends in humanity.

Jessica had become my partner in every way that mattered. We argued about fonts, filed emergency motions at midnight, and learned how to laugh in rooms that had seen too much sadness to handle another ounce. I gave her a key to my house when she locked herself out of her apartment in pajamas once and told her to stash a spare in my junk drawer. She cried. I pretended not to notice. That’s friendship.

One rainy Thursday—because the universe loves a motif—Jessica knocked on my door with coffee and a grin. “The Palmer divorce finalized this morning,” she said, slipping into the chair across from me. “Marcus got the house, both cars, and full restitution. The board suspended Monroe’s license pending the ethics investigation.”

I exhaled. I hadn’t tracked the case closely because it wasn’t mine. It was none of my business, except that it had once been the plot twist in a dinner I would never forget. “How’s he doing?” I asked.

“Better,” she said. “He started a foundation for military spouses who need legal aid. Named it after his grandmother. Delivered the papers himself. Wearing a suit that looked like it knew how to say sir.”

“And her?” I asked, not because I wanted blood but because outcomes matter.

“Moved out of the downtown apartment to a place near her parents,” Jessica said. “Helen volunteers with the support group twice a week. Judge Palmer teaches a pro bono seminar at the law school. He asked if you’d guest-lecture next month on financial infidelity.”

I smiled despite the ache that still ebbed whenever I saw the word infidelity in a font larger than twelve. “I will,” I said. “I will because students need to learn that the law is a refuge for the truth when love gets loud and wrong.”

She handed me another folder. “As for Griffin,” she said, “bankruptcy hearing next week. The Carters withdrew funding. He’s living in East Austin in a studio with a futon and a desk made of penance.”

I couldn’t summon glee. What I felt was simpler: a deep, clean sense that gravity had worked. “Does he have a job?” I asked.

“Junior developer at a startup,” she said. “He coded once. He can again. People can be useful even when they’ve disappointed us beyond a jury’s capacity.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it.

That afternoon, a new client arrived: Mrs. Martinez, small, fierce, hair clipped back with the economy of a woman who has never had the luxury of untangling. “My husband,” she said, hands folded as if in prayer, “has been making payments to something called Creative Marketing Solutions.”

“Tell me everything,” I said. She did. It didn’t take a degree to recognize the pattern. Eight months, thirty thousand dollars, descriptions that lied smoothly. We pulled the LLC filings. We traced the deposits. We saw the connection to an escort service with a deceptively tidy website. We built the case the way you build a bridge across water you can’t drink—carefully, with redundancies, and with engineers who understand that nobody wants to fall.

As we worked, Jessica glanced up. “Do you ever regret it?” she asked. “The public nature of it? Putting on the dress and pulling the cord at Uchi instead of going quietly to a lawyer and letting the community keep its illusions?”

I considered. The rain ticked the window like a metronome for thought. Six months ago, I might have said I regret the pain it caused an older couple handed a bomb when they were trying to eat eel. I might have said I wish Marcus had learned in a gentler place.

Now I knew the answer. “I regret not trusting my instincts sooner,” I said. “I regret letting the small lies stack into a staircase he could climb and run away at the top. I regret that I didn’t buy that black dress for myself earlier, for a day when I simply wanted to feel strong for no one’s benefit but mine.”

“And going nuclear?” she asked softly.

“No regrets,” I said. “There are men—and women—who do their cheating in secret and keep it there. And there are those who use other people’s money and names as fuel. When they pick the public to pay, the public gets to watch the bill collect. I didn’t destroy them. I showed everyone the invoice.”

We finished the Martinez intake and assigned tasks. Ed would untangle the cash flows. Our investigator would trail a schedule we’d already guessed. I’d call a judge on Monday. The machine moved, the kind that wears compassion like thread in its gears.

That night, I poured a glass of wine and walked through my house again, not taking inventory this time but giving thanks to rooms that had learned me as I changed. The living room was mine, the couch a place for friends who did not ask permission to come over and eat pizza on plates because we are adults but sit on the floor because we are still allowed to be children. The kitchen smelled like basil because I had decided to make lemon pasta for myself on a Thursday simply because I could. My office held new binders labeled with names of women I liked and admired and would fight for in ways the law wouldn’t teach you in school.

I slept without dreams.

In the morning, the lake was a mirror. I put on running shoes and circled it twice, passing dogs with rain-shaken fur and men who nodded without assumption and women who met my gaze like we’d read the same book. We had. It was titled How to Live After the Day the World Confessed to You.

Back at the office, a bouquet sat on my desk. No card. Just white lilies and eucalyptus, the smell of clean sorrow. Jessica poked her head in. “Delivery guy said a handsome man in uniform dropped them off and left like he had somewhere honorable to be.”

I smiled. “Marcus,” I said. I didn’t need the card.

I pulled out the unopened letter from my drawer—Griffin’s apology—looked at it one last time, and slid it into the shredder. Paper curled in on itself and died without smoke. The machine hummed, satisfied.

That afternoon, I wrote my guest lecture for Judge Palmer’s class. I titled it “Receipts Don’t Lie: Practicing Law at the Intersection of Love and Ledgers.” The first line said: When someone tells you who they are, believe them. When their bank account tells you who they are, believe it faster.

I printed the draft and left it on my desk. I walked out into the late light and called my mother, who had stayed quiet during the storm because she knows me and because she trusts that I will call when the air is thin again. We talked about weather and casseroles and how her neighbor’s cat had decided their porch was a vacation home. We did not say Griffin. We said love and meant it safely.

Friday’s mail brought the stamped decree: divorce final. The law had done its part. The rest was mine.

Part V:

The view from my new corner office stretched across Lady Bird Lake like a promise. It wasn’t my view by accident. When the settlement checks cleared and the business valuations finished their stately march through spreadsheets, I bought the floor. The entire floor. Not because I needed all that space, but because I needed the symbolism of elevation I purchased with the wreckage I had survived.

Jessica knocked and came in with two coffees and a smile that had discovered new muscles this year. “The Martinez TRO came through,” she said. “He can’t move a dollar without two signatures, neither of which will be his. Also, the reporter from Texas Lawyer confirmed the profile. They want to call you the woman who ‘made financial infidelity indictable in the court of public opinion.’”

“Tell them to call it what it is: consequences,” I said. “I’m not a vigilante. I’m a CPA with a sword.”

She laughed. “You’re an attorney with an army. Speaking of armies—Marcus sent a note.” She handed me a small card. It had only six words, written in precise, sturdy script.

Truth hurts. Mercy saves. Justice restores.

I slid the card into the corner of my monitor. “Hang it above the copier,” I said. “Let everyone read it when the paper jams.”

Jessica sobered. “Do you ever think about seeing them again?” she asked. “Griffin. Monroe.”

“I think about people,” I said carefully. “The specific ones come and go.” I turned to the window. “If I saw Griffin, I’d wish him sobriety, in every sense of the word. Not booze. Reality. If I saw Monroe, I’d ask if she’s learned the difference between need and want. I’d hope she has.”

Jessica nodded. “You’re a better person than I am,” she said.

“I’m not,” I said. “I’m a person who got sick of being angry. Mercy is cheaper than rage long-term. Cheaper and lighter to carry. But it only comes after justice.”

She grinned. “Put that on a mug.”

“I already did,” I said. “Client gifts.”

Our noon consult arrived—a founder’s wife whose eyes had the faraway look of someone reading a text thread that doesn’t exist anymore. I greeted her by name, offered water, and slid the intake form across the table. “I’m so sorry you’re here,” I said. “But I’m glad you found us.”

Her story was different and the same. They always are. The numbers were new and the pattern was old. We moved into work like dancers entering a piece they know by heart and still find beauty in.

At two, my phone chimed with a text from Patricia: Lunch next week? We miss you. I stared at the screen a long moment and typed back: Yes. Wednesday. My office? She responded with three hearts, a maternal grammar I had once expected to be mine.

At three, I delivered my guest lecture. The law students were all energy and eyebrows and expensive laptops. Judge Palmer introduced me without flourish. I stood at the podium and told them the story without names: a woman, a man, a ledger, a dinner, a fall, a rebuild. I watched their faces as I said, “You will have clients who want punishment. You will have clients who want quiet. Your job is not to want for them. Your job is to build the instrument that produces the outcome they can live with.”

When class ended, a young woman with a buzz cut and a serious smile approached. “My dad emptied our 529s to buy a boat when I was twelve,” she said calmly. “He said he’d pay it back. He never did. It’s why I’m here. Not a question. Just… thank you.”

I shook her hand. “You’re going to make a hell of a lawyer,” I said, and meant it so fiercely I had to look away or I would cry in a room full of people allergic to tears.

I returned to the office and found an email from Burke: Griffin signed the last of the docs. He’s asking to meet. Your call. I considered. Then I wrote back: No meeting. I wish him well. Please convey that we are concluded. I hit send. In a movie, the soundtrack would swell. In life, the HVAC hummed.

Evening softened the edges of the lake. The city glowed like an honest ledger—lines and lights and the quiet geometry of things that add up. I gathered my bag, slid the card from Marcus into it, and turned off my office light.

On the way out, I paused at the reception desk. There, in a neat acrylic brochure holder, were our handouts: What to Do When the Numbers Don’t Feel Right. Step one: Trust yourself. Step two: Save everything. Step three: Call us. Step four: Eat something. We’d added that last one after too many clients arrived faint.

I locked the door. The elevator whispered down. In the lobby, I passed a couple laughing the way new love laughs. For a second, the old ache pinched. Then I breathed, and the ache became memory and the memory became story and the story became mine.

Outside, Austin smelled like tortillas and rain on hot sidewalks. I walked to my car, the heels of my shoes clever against the concrete, and drove toward a house that didn’t hold a ghost anymore.

At home, I opened the windows, let the night in, and set the table for one without loneliness. I ate pasta with a book propped open and my phone turned face down, a small act of rebellion against a world that believes a woman alone must be waiting for something.

When I finished, I washed the dishes and placed the plate in the rack like a small, perfect verdict.

Later, in bed, I thought about the night at Uchi one last time—the red dress, the white plates, the moment when truth walked in wearing heels and didn’t trip. I smiled in the dark because the ending had been the beginning, as endings often are. Justice had been served cold that night, and six months later, it still tasted like survival.

In the morning, I would wake and run and work and tell another woman that what she suspected wasn’t a bruise on her imagination but a fingerprint on her bank account. I would teach her how to read it. I would show her how to erase it. I would hand her a pen and watch her sign her name on a future that had been hers all along.

Some stories end with forgiveness. Mine ends with something quieter and more durable. The ledger is clean. The work continues. The woman who made the reservation is still making them—tables, court dates, lives.

And if you are reading this because your Thursdays have started to feel like someone else’s calendar—if your gut growls when the bills don’t add up, if your love no longer resembles your receipts—book the room. Invite the truth. Serve justice.

It will be very, very expensive for the person who thought you wouldn’t.

It will be rich beyond measure for you.

News

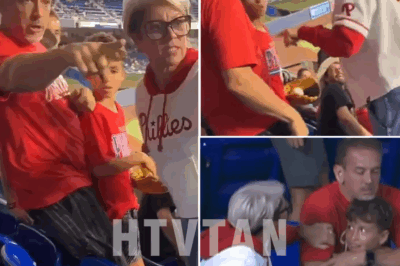

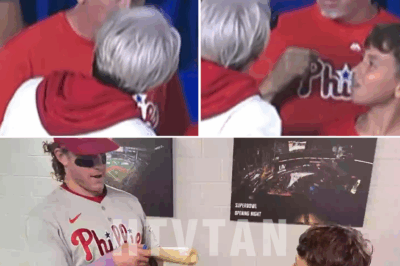

WHO IS THE MYSTERIOUS WOMAN DUBBED ‘PHILLIES KAREN’ WHO SNATCHED A BALL FROM A CHILD AT A PHILLIES GAME, NOW BEING OFFERED $5,000 IF SHE RETURNS IT WITH AN APOLOGY CH2

In a broadcast moment charged with political gravity, Fox News contributor Jessica Tarlov found herself unusually quiet on the day…

SHE GRABBED THE BALL, THE CROWD ERUPTED, AND NOW THE INTERNET IS CHASING THE WRONG WOMAN IN A PHILLIES HOODIE, SPARKING CONFUSION, OUTRAGE, AND A MYSTERY THAT WON’T DI/E CH2

Tarlov Was “Silenced” by Fox News When Trump’s $90 Billion Deal Was Signed On a day when national attention was…

Make Space in Our Home—My Parents Are Moving In,” My Husband Declared Without Warning. CH2

Emily was at her desk when a knock sounded at the study door. Oliver stepped inside, glancing around the familiar…

You wanted to take my apartment and my savings? A pity I turned out to be more farsighted, isn’t it, Maxim?” I smirked, looking him straight in the eye. CH2

Elena woke first, as always. Maxim was asleep beside her, his arms stretched out over the blanket. Sunlight filtered through…

You’ll Always Be Poor and Stuck Renting,” Said My Mother-in-Law. Now She’s Renting a Room in My Mansion. CH2

“You’ll always be poor, stuck renting some dingy flat,” her mother-in-law had sneered. Now, the woman rented a room in…

”You’re Just a Maid,” My Mother-in-Law Mocked—Not Knowing I Owned the Restaurant Where She Washed Dishes for 10 Years. CH2

“You’re just a servant,” sneered my mother-in-law, unaware that I owned the restaurant where she had washed dishes for ten…

End of content

No more pages to load