Part I

I didn’t have the confirmation numbers for the reservations I’d supposedly made—funny how memory buckles when your gut already knows the truth—so I did the next best thing: I drove to the most likely hotel and walked straight into the lobby like I belonged there. Upscale boutique place. Lots of velvet, lots of curated jazz humming through invisible speakers, a forest of soft lamps pretending darkness was a choice. The front desk guy gave me the polite once-over you give to someone who might tip heavy or complain louder. I gave him a nod back and drifted toward the elevators.

My plan was half-formed at best. The kind of plan you pretend is a plan so you won’t admit you’re improvising your way through a panic attack. I figured I’d check the eighth floor—because the Instagram story I had doom-replayed fifty times showed a corridor with cream carpeting and a little brass plaque that, when I zoomed in hard enough to see individual pixels, looked like it said “8.” That, and because I’d just spotted Kalin’s car in the half-circle drive outside, idling near the entrance like a dare. If that wasn’t a sign, I didn’t know what was.

The elevator crawled upward, a silver box counting by soft pings. My reflection in the mirrored panel looked like a man who’d lost his wallet and his future simultaneously. When the doors parted, the corridor was empty—just the hush of expensive carpet and closed doors humming the private lives behind them. I walked, breathing too shallow, eyes scanning door numbers. 842. 844. 846. The air smelled like lemon and money. At 847, my lungs forgot how to work.

The overhead lights felt too bright. The windows at the far end were night-black mirrors. Somewhere down the hall, an ice machine sighed; somewhere nearer, I swear I heard a heartbeat and only later realized it was mine. I cocked my head toward the polished wood, listened, heard nothing. Silence is its own confession when you want to hear something—anything—else.

I tried the handle. Just a light test, enough to know if the deadbolt was thrown. It wasn’t. The door sat there with the lazy confidence of someone who thinks consequences are for strangers. I slipped a hand into my pocket and found the master key card Kalin had given me a month earlier in the name of “wedding emergencies.” He’d said it in that easy, practiced tone: Just in case you need to get into a guest’s room, man. Terrible lockout stories at weddings. You never know.

I knew now.

When the green LED winked, everything in me went quiet—the way the world sometimes dims right before lightning strikes. I opened the door a few inches and slid inside, soundless on the carpet. The room was dim, the kind of low light hotels use to soften edges and encourage you to forget the cost of the minibar. Curtains half-drawn. A tray with two champagne flutes, one tipped, lips marked in a shade I recognized too well. And the bed—

The bed was a constellation of limbs.

Holly, my wife of nine months, lay sideways across the king, hair fanned, a sheet rucked around her hips. Kalin was bent over her from the right, hand braced in the mattress like a pledge. And on the other side—God—Nico, the friend from pickup basketball, from Sunday cookouts and fantasy leagues, who texted in abbreviations and laughed in whole minutes. Holly between them, cheeks flushed, a private geography of trust inverted into something I could not name without tasting metal.

It wasn’t graphic the way a movie is graphic, yet it was more than graphic because it was real. Holly’s hand touching Nico’s shoulder with familiarity, the way she tucked her chin when Kalin said something in that conspirator’s half-tone lower than a whisper. It was without question. It was exactly what I already knew and still couldn’t believe.

Some buried animal in me lunged toward violence. My fists went hard as if gripping an invisible steering wheel. I could have shouted; I could have flipped the bedside lamp across the room like a comet; I could have made the kind of mistake you remember in a courtroom. But some smaller, colder voice rose up and saved me.

Stop. No reaction. Proof.

I slipped my phone from my pocket and opened the camera. There are a thousand everyday motions you do without thinking. Unlocking your screen, swiping to video, tapping the exposure up a notch, making sure the timestamp burns itself into the lower right. I did them all as if I’d been practicing for this very moment, as if somewhere in my lizard brain I knew one day I would document the end of something I once believed indestructible.

The sound on that recording—if you played it back—would be the low hush of a central air unit and the catch in my breath that I tried and failed to swallow. It would be Kalin’s murmur, a smirk laid across syllables: Don’t worry. We’ll never get caught. It would be the slide of bedding, the quick bubble of Holly’s laugh, a sound I used to wear like a medal.

Nico’s face tipped up once, just enough that the lens caught his profile, which meant it caught everything about who he was to me. A year of beers, of scuffed sneakers, of “we good?” texts, of borrowed sockets and shared playlists. A guy who once sat on my couch to hold a light while I installed a ceiling fan. The guy who promised to plan my bachelor party if Kalin ran late. The guy my wife waved to without looking up from the salad she was tossing because he’d been to our place so many times it was muscle memory.

I filmed long enough for a judge and short enough for there to be no chance they’d turn and spot me. I pulled back toward the door, my hand steady the way hands sometimes steady in immediate crisis because they know the tremors will own them later. I clicked the handle shut behind me and didn’t run until the elevator doors blessed me with their stainless-steel mercy.

Outside, the air had that full-night cold you only feel on the back of your teeth. I walked without choosing a direction; my body reached the car and folded itself into the driver’s seat as if it belonged to someone older. The city at 1:00 a.m. is a fairground of neon and bad ideas. I let the road have me. I drove until the gas light yawned awake and a 24-hour diner appeared like a cliché that didn’t care it was a cliché.

I slid into a cracked vinyl booth and watched my recording on loop under a fluorescent buzz that made everything look more honest than I could stand. The timestamp was perfect. The faces were perfect. The betrayal, impossible to misunderstand.

That was when the plan stopped being half-formed. It didn’t arrive fully dressed; it came as a shape of necessity. The wedding—ours, mine, hers, theirs—was scheduled for noon at the Wentworth Country Estate with its chandeliers and sconces and a staff that moved like a ballet you dumped money on. Our AV package was “gold tier.” I had spent an entire evening with the technician, Tony, learning how to swap feeds, how to nudge volume, how to bypass the slideshow for a surprise song. I’d joked about pranks—shoestrings and hidden playlists—and Tony had said, I can roll with most things. Just don’t get me fired.

I pictured the ballroom, the dais, the stage lights aimed for tears and toasts. And then I pictured the screen.

It would be easy. It would be unforgivable. It would be mine.

I ordered coffee. I ordered it again because ordering is a way to avoid thinking. I scribbled on a napkin: “Ladies and gentlemen…” Lines that started with courtesy and ended with rupture. The phrases didn’t feel like words; they felt like turning a wheel across black ice and hoping the car would listen. Somewhere between 3:00 and 5:00 a.m., I shifted from planning to rehearsing. Somewhere in the small hours, the shaking stopped—not from peace but from the exhaustion of holding every muscle clenched for too long.

At dawn, the sky limped gray over the diner’s windows. I paid the bill with a hand that had become a stranger to coins. I drove home. The apartment I shared with Holly looked the way a staged apartment is supposed to look—throw pillows, a candle that smelled like a season you idealize. Her charger on the nightstand, ring box glinting on the dresser, the vacuumed lines in the carpet too straight to be real life. I closed my eyes and pretended to sleep the way children pretend to be statues.

At nine, the lock beeped softly. I didn’t move. I listened to her walk to the guest room because even lies respect muscle memory. When I wandered out, I met her smile and her easy story—too much wine at the rehearsal, crashed with a friend, you know how it is. I knew how it was, and it was not that.

“Must’ve been some party,” I said, kissing her cheek like an actor hitting his mark. The performance tasted like tin.

I could’ve said more. I didn’t. There was a noon ceremony to prepare for. There was a ballroom that did not know it was about to become a courtroom. There was a groom who would not stand where everyone expected him to stand. There was a wife who would not be a wife by sunset.

And there was a video on my phone, patient as a lit fuse.

Part II

The Wentworth Country Estate was born for wedding magazines. The driveway curled through maples like a wrist showing off bracelets. White stone flanked a fountain, horses carved mid-rear, water frozen into arcs of money. Inside, the foyer breathed money too: gold-leaf cornices, a chandelier that might as well have lowered itself from the ceiling with its own fanfare. If I’m honest, I chose the place because Holly wanted it and my mother used words like “elegant” the way some people use words like “holy.” The Wentworth had history, they said. As if history is a talisman protecting you from the future.

I arrived three hours ahead, beating the florist by fifteen and my parents by forty. Tony, the AV guy, wore his headset like a halo and his anxiety like a second headset. “My man,” he said, nodding as if we were conspirators across a poker table. “We’re all lined up for your montage—baby pics, college antics, the whole meet-cute to now. I swapped in the new music you sent. You want to run it once?”

“It’s perfect,” I told him, because something had to be. “I’m queued a surprise, though. Quick swap at my signal.”

His eyebrows tried to flee his forehead. “Surprise-surprise? Or the kind of surprise that gets me written up?”

I smiled in a way that made him laugh, then frown. “It’s your wedding, man,” he said. “I can roll with most things. Just don’t get me fired.”

I touched the pocket where the flash drive lived, its edges crisp against the fabric like a secret square. The room smelled like lemon polish and adrenaline—the latter was mine. I walked the empty aisle, felt the rich carpet take my weight like a confession. I stood at the altar and looked out at rows of chairs that would hold people who loved us, people who tolerated us, people who came for the open bar and the buffet, people who came because weddings are theater and no one wants to be caught missing the scene everyone talks about later.

My parents arrived first. Mom wore a pastel dress that insisted on hope. Dad’s tie matched it without irony. When they hugged me, I felt the kind of guilt that rents space behind your sternum and brings its own furniture. “We’re so proud of you,” Mom said, eyes bright. Dad squeezed my shoulder like an old teammate saying “you got this” because that’s what men say to each other when nothing about it feels like sports.

Holly’s side was a phalanx—family with money, associates with power, aunts with sharp glances that could serrate bread. Marjorie, her mother, wore lilac and judgement. Richard, her father, burst in like a businessman late to a merger, phone in one hand, an opinion loaded in the other. “There’s our groom,” he boomed when he spotted me, gaze raking my suit not from admiration but quality control. “Looking sharp. Keep it together, son. Lot of important eyes today.”

I thought of the video timestamp like a loaded chamber and said, “Yes, sir,” because what else do you say to a man whose flaw isn’t that he thinks he owns you but that he’s right that he owns most rooms he walks into?

The bridesmaids moved through the ballroom like swans in training. The groomsmen—all but one—made sure everyone knew they were fun but not unreliable. Kalin sent me a text around 11:20: “You good?” The kind of question you ask when you mean, You on script? Nico didn’t text. Maybe he was off somewhere learning what shame tastes like. Maybe he was fixing his cufflinks and not thinking of anything at all.

By 11:50 the staff had ushered guests into their seats, the whispering orchestra of chatter swelling, dipping, swelling again. The officiant—a friend of the Chambers family who always bragged about having a certificate he printed out in 2011—stood at the front, shuffling his notes like a deck he planned to lose at. The plan was simple: groomsmen first, then bridesmaids, then a flower girl scattering petals like miniature absolution, then Holly, radiant, everything forgiven. That was the theatre of it.

I wasn’t at the altar.

At 11:55, the officiant peeked around the backdrop, looking for me. At noon, a murmur moved through the rows like wind through a wheat field. At 12:01, I walked the opposite way of everything I had planned for a year and climbed the stairs to the AV booth.

“What’s up?” Tony asked, eyes on his console, voice tight. “We’re two minutes behind.”

“It’s okay,” I told him, slipping the flash drive into his outstretched hand. “We won’t be doing the montage just yet.” I lifted the spare mic, the one you use for toasts and late-night drunk uncles insisting the DJ play one more Springsteen track. The ballroom lights caught my reflection in the booth glass; for a sliver of a second I saw a man I would not recognize six months from now and I pitied him.

I thumbed the mic on.

“Good afternoon,” I said. My voice floated through the room and returned to me hollowed by acoustics. Conversation stopped the way birds do when a shadow passes. Heads tilted in unison, an instinct as old as plains and predators.

“Daniel?” the officiant asked into his own mic, blinking at the ceiling as if God had chosen a new, more petty angle for revelation. “We’re ready to begin. Everyone’s seated.”

“Actually,” I said, “there won’t be a ceremony.”

No line reads prepare you for that one. The sound was a collective inhalation, a theater’s worth of lungs schooling themselves for outrage. It wasn’t quiet, but it was a silence in practice: shock rehearsing itself loudly.

I kept breathing because it was either that or fall. “Before you get too upset,” I said, aiming for a calm that sounded like ice, “I want to show you something. Tony, would you roll that file?”

Tony’s eyes went wide enough to read the serial number on the back of his iris. He clicked, hesitated, and clicked again because hesitation doesn’t change outcomes, only schedules.

The screen—the glorious, ridiculous screen—went dark for a heartbeat. Then it brightened into a grainy still, steadied, and became the kind of video a room can’t look away from because it doesn’t know which parts of itself it should cover.

I wasn’t cruel enough to play everything. I wasn’t kind enough to play nothing. Ten seconds is longer than it sounds. Long enough to recognize faces, to parse a timestamp, to understand a posture, to hear a line that turns acrylic chairs into jury boxes.

Don’t worry, Kalin’s voice said, edged with a confidence most people call cowardice in hindsight. We’ll never get caught.

Aunt someone shrieked Oh dear Lord like the line had waited its whole life in her throat for this precise cue. Richard swayed; Marjorie’s mouth bent into a geometry no etiquette book prepares you for. Somewhere a bridesmaid made a whale sound and somewhere else a groomsman whispered how badly he wished he were anywhere but here.

I killed the feed at ten seconds because mercy is still mercy if it’s late.

The screen went black; the room didn’t. The room fractured into a hundred small reactions and a dozen large ones. In the doorway opposite the aisle, Holly appeared framed by carved wood and expectation. She was stunning in the way a warship is stunning, all sleek lines and latent function. Her face, perfect under makeup that had cost two hundred dollars more than I thought reasonable, reeled in understanding.

“Turn it off!” she screamed—never mind the screen was already lifeless. “Who did this?”

Her mother lunged toward the AV table as if she could drag the humiliation out through the cables. The officiant stood useless as a washcloth tiered into a cake. Tony ducked as if shame were an airborne hazard.

Richard thundered the way men thunder when they want to intimidate the weather. “Daniel!” he roared, neck swelling, fists ready for someone else’s mistake. “Get down here!”

I took the stairs because a good performance demands an exit. Holly’s eyes found me at the landing and hardened into something that used to be love and now was almost hatred but not quite, because hatred would have made this simpler.

“What are you doing?” she tossed up at me, voice cracking into two. “You’re not supposed to see me before the wedding!”

There is a version of me from last year who would have laughed. The version who stood there didn’t laugh. “There is no wedding,” I said, and the mic caught the steadiness like a lesson. “You made sure of that last night.”

She went still, and when people go still like that they are calculating, not crumbling. “Let’s just talk. Not in front of everyone. Please.”

“Why not?” I asked. “You had no problem doing this in front of yourself.”

That was when Kalin appeared, tie limp, hair not yet fixed into his public-facing neatness. He looked like a man rushing into a fire he misread as a candle. “Bro,” he called, which somehow made anger easier. “Let’s talk.”

We met at the foot of the aisle, the carpet swallowing footsteps that deserved to be louder. Holly hovered, torn between repairing optics and dealing with casualties. I wanted to speak, to parse, to debate—but a hard clarity had settled over me and my hand moved faster than any sentence.

The slap cracked across Kalin’s face and echoed in a room designed to applaud. He reeled, stumbled, sat with a thud some part of me cataloged as satisfying. The gasp that followed belonged to one organism, not many.

“Stop!” Holly cried, kneeling as if the dress could forgive the bending. “You’re hurting him.”

“I didn’t bring him here,” I said, breath measured like a class. “He brought himself.”

I looked out at the room—friends with phones half-raised, relatives shielding children from words the children would repeat later, coworkers filing this into stories for holiday parties. “Thank you all for coming,” I said with a formality that tasted like rust. “There will be no ceremony today. You deserved to know why.”

I set the mic down and walked out through doors so heavy they make you reevaluate your relationship with gravity. Behind me, the day fell apart the way only well-planned days can. Ahead of me, the parking lot offered a blue sky inappropriate for the occasion. My parents followed, and my father’s hand found my shoulder again, steadying the tremor I had managed to evade until that minute.

“You did what you had to,” he said, voice low. My mother was crying, not the hiccuping sob of the movies but a quiet, even leak, the plumbing of sorrow.

“I’m sorry,” I told them both, and meant it, though not in the way apologies usually mean themselves. I wasn’t sorry for the truth. I was sorry for every photograph in a box that would go unopened now.

Part III

When I got back to the apartment, the quiet felt like it had a witness. I opened the bedroom door and the morning we’d left behind was still arranged on the dresser like an alibi—ring box upright, lip balm, a hotel matchbook we kept from the weekend we got engaged, back when the idea of permanence tasted like champagne. I wanted to lie down, but lying down felt like surrender, so I sat on the edge of the bed and stared at a scuff on the baseboard as if it could explain any of it.

My phone vibrated with the hunger of an animal. Messages stacked: Did that really just happen? / Are you okay? / Daniel, call me / Holy hell, dude / You’re trending in my group chat / This is not the way. I didn’t answer. There is a window after a catastrophe when everyone thinks they’re the best person to hold your hand. They mean well. Sometimes you want to bite.

I showed my parents the unedited clip because love deserves the courtesy of evidence. Mom watched, hand over her mouth. Dad watched, eyes hard, jaw clenched, the way a man watches a news segment about something unjust he can’t fix. When it ended, none of us spoke for a few seconds that went on too long to be spaces between words.

“Oh, Daniel,” Mom finally breathed. “I’m so, so sorry.”

“You got out,” Dad said, and the sentence carried the weight of mortgages and retirements and disappointments and all the quiet tricks people use to stay married when they shouldn’t. “You got out before it got worse.”

They left with the gentleness of people backing away from a wounded animal, promising dinner later and space now. The door clicked shut like an endnote.

I didn’t pack out of vengeance. I packed out of logistics. Holly’s clothes were a taxonomy of seasons. I never noticed how many shoes she owned because shoes live on the periphery until they don’t. I labeled boxes out of habit—DRESSES, HEELS, MAKEUP—like I was arranging a yard sale of a former life. I moved quietly because quiet made me feel like I hadn’t lost everything. At midnight I rented a U-Haul trailer and the guy at the counter said “Big weekend?” with a kind of cheer only strangers can muster. “Something like that,” I said, and we moved on.

The Chambers house wore its wealth like a uniform. The gate guard recognized me, eyebrow tilting at the trailer. “Everything okay, Mr. Harper?” he asked, and I almost laughed at the formality, at my last name turned inside out by this day.

“Just returning Holly’s things,” I said. He buzzed us through with a sympathy he probably used on half the divorced dads in the zip code.

I stacked the boxes on the stone porch with their labels neat and visible because neatness is a love language and also a middle finger if you use it right. I rang the brass knocker once, plainly. In the foyer, a light came on, slow and astonished. I didn’t wait. You can only narrate a single day for so long before you run out of voice.

I slept for the first time in thirty-two hours and dreamed nothing, which felt like grace.

The knock on my door at 8:15 a.m. wasn’t polite; it was the sound you make when you think a door owes you money. I opened it to find a tableau: Holly in sweats, eyes swollen and hair ungoverned; Richard in a suit that thought it could scare me straight; Marjorie holding a manila folder like paperwork alone could reroute time.

“We need to talk about compensation,” Richard said, voice the temperature of boardrooms.

I leaned against the frame. “For what?”

“The wedding,” Marjorie snapped, thrusting receipts at me. “The fiasco. The hotel bookings. The catering. The embarrassment.” She said the last word as if she’d spat a cherry pit into a handkerchief and wanted me to handle the rest.

“You do realize,” I said, calmly because calm is a weapon and I needed one, “that your daughter cheated on me the night before our wedding? With two of my friends.”

Holly flinched as if the number mattered now. “It was a mistake,” she said, reaching for contrition and catching only justification. “We were drunk. You canceled the wedding like a psychopath. You could have called it off quietly.”

“I tried the quiet option last night when I stood outside a door,” I said. “Quiet didn’t work.”

Richard stepped forward, filling the doorway with an energy that once cowed interns. “We covered more than half the costs. Your parents paid their share, but the extras—well, those weren’t cheap. We expect fifteen thousand from you. Today.”

I should have laughed. Instead, I let my face do nothing. “You’re asking me to reimburse you for a party you ruined,” I said. “I won’t be writing that check.”

Marjorie sniffed disdain into the air. “You humiliated our family.”

“You humiliated yourselves,” I said. “I illuminated it.”

Holly’s voice broke as she tried on a different tactic. “Daniel, please. We loved each other, once. Let’s just sit. We can sort it out. Don’t destroy everything over a single—over this.”

One thing about a certain kind of plea: it presumes you haven’t already fallen through the ice. “I’m not paying you fifteen grand,” I repeated. “I’m not paying you fifteen dollars.”

Richard’s jaw worked, a man unused to “no.” “You don’t know who you’re dealing with.”

“I do,” I said. “You’re the father of the woman in the video with the timestamp. If you want to go public with a dispute, we can do it in a courtroom—or a Facebook neighborhood group. Either way, the tape plays. Pick your venue.”

He hesitated because money hates bad publicity the way cats hate bathtubs. Not fear. Calculation.

“You’ll regret this,” Marjorie said, like a curse she’d learned in finishing school.

“Not like I’d regret marrying your daughter,” I said, and it came out so easily I almost forgave myself for enjoying it.

They left in a storm of exhalations and expensive cologne. The hallway felt two sizes bigger after the door shut. I stood for a long minute in the living room and listened to the clock pretend the world still moved at the same speed.

From there, life did the thing it always does after you blow it up. It tried to hand me a broom.

The calls kept coming. The texts thinned and concentrated around the people who matter. My friend Julia brought hummus and a bag of uselessly fancy crackers and said nothing for thirty minutes because that’s friendship, not whatever Kalin or Nico had been selling me. My boss sent an email with the subject line “take the week” and no body, which felt like an apology wrapped in a favor.

Kalin texted: “Dude I’m sorry you don’t understand.” I blocked his number. Nico never texted. Maybe because shame works better without an audience.

The story did its rounds. I ignored the parts of it I could not control because trying to manage gossip is like trying to manage weather patterns: you can do it for a second, and then you remember you’re made of human. Someone told me Kalin lost his job. Someone told me Nico moved out of his girlfriend’s place and into his cousin’s. Someone told me Holly went to stay with her parents, and there were fights you could hear from the sidewalk if you lingered near the hedges. People tell you this because they think it will make you feel better. It doesn’t. It makes you feel indictable, like someone else’s consequences can be credited to your account.

Still, there were practicalities. I moved to a cheaper apartment. I returned gifts with the thank-you cards we’d never sent. I split the guest list into three piles: people who called me, people I called, people who didn’t need to be in my life at all. I updated passwords because betrayal teaches you IT policy better than any training module.

And every so often, when the night grew noisy with all the sentences I didn’t say in that ballroom, I played those ten seconds—not because I needed to confirm what happened but because I needed to confirm that I hadn’t imagined any of it, that it had been as clear as it felt. Proof is a cold companion. Sometimes cold is better than company.

Part IV

There’s a stretch after a rupture where every day is a version of the day you just had—muted, reworded, but recognizably kin. The coffee you make tastes like the coffee from the morning before you blew up a wedding, because coffee is indifferent. The sun climbs up like it’s getting paid by the rung. On Tuesday, a barista misspells your name and it’s almost funny. On Wednesday, you get halfway home and realize you left your laptop on your desk at work because your brain has become a pocket with a hole in it. On Thursday, you wake at 3:17 a.m. convinced you’ll never feel normal again.

Then one morning—maybe a month out, maybe two—you stand in line at the DMV and realize you’ve just spent sixty seconds thinking about something else. It’s almost insulting that healing works this way, by accident.

The city moved on, which struck me as both cruel and instructive. The people who’d filmed parts of my life at the Wentworth uploaded, captioned, moved on to the next spectacle. There would always be next spectacles. I learned to live with the ghostly idea that strangers I’d never meet could identify me at a farmer’s market from a certain angle and a certain half-smile that said, That guy. The one with the video.

I went back to work after a week that wasn’t really a week because time is a stretchable fabric when you’re holding it at either end. Coworkers performed that hallway shuffle where you want to offer condolences over an un-death. “Hey, man,” said Mike from Sales, hand hovering above my shoulder like a drone. “You good?” The answer you give makes them feel better, not you. “Yeah,” I said, and left it there.

Julia became a fixture, not because I was drowning—though sometimes I was—but because we were two people who had shared enough ordinary that we could stand a long stretch of extraordinary without burning out. Every Wednesday we hit a diner two blocks from my new place, the kind of joint where no one cared if you ordered breakfast at nine at night. She insisted the pancakes tasted like hope. I ordered scrambled eggs because order is a form of prayer.

“Do you still have it?” she asked one night, syrup pooling around the edges of her plate. She didn’t need to specify it.

“Yeah.”

“Do you watch it?”

“Sometimes.”

“Does it help?”

“Not the way you think.”

“How, then?”

“It reminds me reality exists. That I didn’t invent the worst day of my life just to give myself an origin story.”

She nodded and stabbed a slice of pancake, like absolving batter with cutlery. “Origin stories are useful,” she said. “They make comic books work. But you’re not a superhero, much as I hate to break it to you. You’re a guy who did the honest thing loudly. There’s a cost to loud honesty.”

A month after the Wentworth, I saw Nico at the gym. It was a Tuesday, which is the day men who believe in rituals but not religion tend to lift. He wore a hat pulled low and sunglasses inside like an idiot, which I suppose is a synonym for contrition these days. I saw him see me, the way his body flinched like a deer caught in the democracy of headlights. He turned toward the locker room.

I followed.

He was standing with his hands on the bench like a man mid-prayer. He looked smaller without the group around him. Shame subtracts inches.

“I have nothing to say you want to hear,” he said, voice rough.

“You’re right.”

He exhaled. “It wasn’t supposed to happen.”

“That sentence,” I said, “has never meant anything.”

He swallowed. “I keep replaying—”

“Don’t,” I said. “I replay enough for both of us. For free.”

He nodded, then winced at his own nod. “I’m sorry.”

“Good,” I said, and realized I meant it. “Now be sorry in a way that changes how you live. That’s the only currency that spends.”

He didn’t look up. I left him there, a piece of scenery in a gym where men pretend machines can fix what’s wrong with them.

I didn’t see Kalin. He had the good sense to orbit elsewhere. Occasionally, a mutual friend would cough up an update the way you cough up something you accidentally swallowed. He’s crashing with a cousin. He’s interviewing. He’s saying he made a mistake but that you shouldn’t have—well, you know. The you-shouldn’t-have got less specific over time, which told me he was learning. Or lying differently.

Two months out, I received a letter with a letterhead whose font tried to make it sound less like a threat. It was from the Chambers’ family attorney—a politely acidic request that we “resolve outstanding financial matters related to the canceled event.” It was written in that voice legal English uses when it wants to sound factual while auditioning for intimidation. I forwarded it to a lawyer a friend recommended, paid a consultation fee that hurt a little, and felt better anyway. My guy sent back a reply that was both art and bat. The short version: We decline. We further invite you to consider the reputational risks of any future escalation, given documented evidence, etc., etc. Sometimes the right sentence is a shield. Sometimes it’s a door you shut with an audible latch.

The letterhead’s office did not write again.

At the three-month mark, my mother called to tell me she had finally stopped crying at random songs in the car. “I didn’t realize how many radio hits are about betrayal,” she said, and laughed in a way that felt like it might work again. “I miss you coming over for Sunday dinner.”

“I’ll come,” I promised. “This week.”

“Bring anyone?” she asked gently.

“No,” I said. “But not because I won’t, ever. Just not yet.”

Holly texted exactly once in that entire stretch. A message without punctuation, like grammar had given up: I know I ruined it I was scared and stupid and selfish I’m sorry forgive me. It was the only language left that no one else could write for her. I stared at it for a full minute and then typed a reply I didn’t send for another full minute.

I forgive you, I wrote, and felt the words resist. Not because you deserve it. Because I do. Please don’t contact me again.

I hit send and watched the bubble land. The screen did nothing, which is how absolution works most of the time. Not a bolt of light. Just the quiet that comes when you stop holding a grudge like a hot pan with your bare hands.

In late September, I moved apartments again. The new place had creaky floors that complained like honesty. The street out front hosted a parade of dogs who walked their people. The first night, I lay awake listening to a neighbor play guitar in the slow, patient way of someone who isn’t very good but really wants to be. It made me oddly happy.

That weekend, I box-cut the last of the old life—the crate with the “WENTWORTH—PLACE CARDS?” label written in Holly’s looping hand, the wedding favors we never tied ribbons to. At the bottom lay the flash drive I’d used in the booth. I twirled it between finger and thumb, the plastic warmth to the touch. I could have hurled it against the wall and watched it shatter. I could have put it on a chain and worn it like a trophy. Instead I slid it into a drawer labeled TAXES, because what else do you do with the physical form of your worst memory but file it next to other painful necessities?

On the first Sunday in October, I went for a run at a park by the river. The sun did what it does best in October—pretend it’s warmer than it is. Leaves got on with their busy dying, flamboyant about it. On a bench, a couple laughed, heads tilted toward each other like parentheses. For a moment I felt the familiar blade between the ribs—the one that insists You will never have that again—and then, like a muscle that had been strengthened quietly, my brain returned: That’s not true. It might not be today. But it will be a day.

I stopped at a coffee truck whose barista had a tattoo of a lighthouse and a grin like a dare. She handed me a cup and said, “Long run?”

“Long year,” I said. We both smiled, and it didn’t hurt.

Part V

You don’t get epilogues in real life. You get Tuesdays.

Mine arrived six months after the Wentworth. Spring pressed its ear against the city and listened for us. On a Tuesday I found a card in my mailbox addressed in handwriting I didn’t recognize. Inside was an invitation to a small gallery opening—photographs of “urban moments,” it said, the kind of phrase that could mean anything. There, near the bottom, was a name I did know: Julia. Of course it was.

I went because you go to your friend’s things. The gallery sat two floors up in a building that used to be a warehouse and now survived by selling stories to people who like exposed brick. The photographs were black-and-white and not precious about it. A kid leaping a puddle. A woman counting coins at a bus stop. A man staring at a pawnshop ring in the window like it was both an apology and a dare.

“You came,” Julia said, appearing at my elbow like a magician with good timing. She wore a blazer that made her look like a serious person and sneakers that insisted she still knew how to run. Her smile was a relief.

“Wouldn’t miss it,” I said. “These are good.”

“They’re fine,” she said, rolling her eyes. “But I’m proud anyway.”

“Be proud,” I told her. “Pride has to live somewhere.”

She looked at me, head tilted, as if measuring something. “You look less haunted,” she said. “I don’t know what the opposite of haunted is. Blessed? That’s gross.”

“Booked,” I offered. “As in, the ghosts tried to get a table but I told them I’m booked.”

She laughed, and it was the kind of laugh that sends a small messenger to move furniture inside your chest. “Come meet someone,” she said, hooking my sleeve with a finger. “She’s on the board here. And she’s… I don’t know. She seems like your kind of person.”

I registered the pronoun and didn’t panic. We crossed the room. A woman stood by a photograph of a dog mid-shake after a rainstorm, water flaring off in a halo that had more joy in it than some churches. She wore a slate dress and boots that had done actual work. Her hair was pulled back in a way that didn’t apologize for her face. When she smiled, it traveled all the way to her eyes, which made me want to follow.

“Daniel,” Julia said, “this is Mara. Mara, this is the poor man who let me text him fifteen drafts of my caption labels.”

We shook hands. “I’m the one who told her to cut the adjectives,” I said. “So if you hate the labels, blame me.”

“I love a good noun,” Mara said. “Solid, confident. Goes with everything.”

“I’m a big fan of verbs,” I said, and then—because a man who destroyed his wedding has to be careful with words like flirt—stopped.

We stood there. The photograph of the dog flung joy onto all of us whether we asked for it or not.

“So,” she said. “Nouns. Verbs. You’re a writer?”

“I’m a project manager,” I said. “Which means I write emails. And spreadsheets. And the occasional apology.”

She smiled. “I work in historic preservation. Which means I spend a lot of time telling people not to paint over their past with cheap beige.”

“Sounds like noble work,” I said.

“It’s mostly meetings,” she said dryly. “And being lied to by landlords. But it has its moments.”

“Like dogs exploding with water.”

“Exactly,” she said. “Like catching a city doing a small, perfect thing.”

Julia drifted away with the practiced invisibility of a good friend who knows she’s performed her function. We stood with the dog picture, and conversation did the trick it sometimes does—forgetting to be effort.

I didn’t tell Mara about the Wentworth. You can’t lead with a fire. Instead, we talked about tacos. About how autumn smells like pencils. About a song that feels like windows down. She asked if I liked to cook, and I said I could do a chicken thighs thing that won friends and influenced no one. She laughed, and it wasn’t a test, and I realized my brain had stopped scouring her freckles and haircut for signs she might be the kind of person who would hurt me. That felt like a small, unadvertised miracle.

At nine, the gallery lights flickered the way all galleries flicker when they want you out. She looked at me then, one eyebrow raised, as if to ask if this had been a conversation or a practice conversation. I decided to take back a thing I used to be good at.

“Would you like to get coffee?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, without performance. “I would.”

We picked a day that had the decency to be close and a place neither of us claimed as territory. That night I walked home past shop windows reflecting a version of me I didn’t hate. In bed, I stared at the ceiling and didn’t feel the weight I’d expected to feel. It was light, the way something is light when you set it down after carrying it farther than you had to.

The next morning, my phone buzzed with a number I didn’t recognize. It was a voicemail, because phone calls are now either emergencies or accidents. I listened because curiosity is genetic. The voice was Richard’s—smaller, like someone had moved him to a room where echoes didn’t work.

“Daniel,” he said. “This will be short. I… We should have handled things differently. I should have handled things differently. I’ve been angry in the wrong directions. I heard you told Marilyn you forgive Holly. That matters. You don’t owe me a response.”

He paused, as if waiting for a teleprompter only he could see. “I hope you find… I hope you’re well,” he said, picking a word he could say without breaking a tooth on it. “Goodbye.”

I sat with the message long enough to be sure it was real. Then I deleted it. Not because I didn’t care, but because keeping it would have made me the archive of someone else’s late learning. The past didn’t need my storage anymore.

Coffee with Mara landed in that sweet spot where conversation hums and quiets and hums again without anyone checking the exits. She listened the way you do when listening is your idea, not an assignment. At some point, because it would have been dishonest not to, I told her about the video and the ballroom and the ten seconds that ended a chapter.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and it sounded like a good apology—one that asks for nothing in return.

“Me too,” I said. “And I’m not.”

“That’s how you know you’ve got the right angle on it,” she said. “You can hold both.”

We walked out into a spring afternoon that pretended it had invented blue. At the crosswalk, a kid on a scooter zoomed past, trailing a red ribbon like punctuation. We laughed because it was impossible not to.

The thing about endings is that no one rings a bell. There’s no sign over a door you get to walk through that says “Old Life” on one side and “New Life” on the other. Most of the time, endings are a series of little permissions you give yourself. It’s okay to throw out the mug you bought together. It’s okay to keep the mug because you like the handle. It’s okay to say the word wife out loud and not hear it echo. It’s okay to take a stranger’s number, to tell a friend you’re not ready, to believe in the common miracle of groceries.

A year to the day after the Wentworth, I stood on a different kind of floor—a hardwood living room in an apartment whose windows faced west. The sun threw itself across everything like a friendly drunk. There were two coffee cups on the table and two pairs of shoes by the door and a bookshelf with a copy of a novel I’d once pretended to have read and then actually read because some people make you better in ways you don’t see coming. Mara was in the kitchen arguing with a basil plant. “Grow,” she said sternly at it. “Do your job.” She caught me watching and smiled in that way of hers that pulled the room around it like a scarf.

“Want to help me decide if we’re brave enough to make risotto?” she asked.

I pretended to weigh it. “Risotto is practice for faith,” I said. “You stir and stir and trust it’ll become something.”

“Which is a lot to put on rice,” she said.

“It’s resilient,” I said. “It can handle it.”

We cooked. We burned a pan. We laughed. After dinner, we sat on the floor because chairs felt too formal for a Tuesday and we were not formal people. We talked about lighthouses and verbs and whether or not there are such things as signs. I thought of Kalin’s car that night, parked at the hotel entrance like omen and theater prop, and how I’d once believed in signs the way some people believe in cold reading. I thought of how little I believed in them now, and how much I believed in choices.

I still had the video. It lived in the drawer where I kept taxes and warranties and other proof that life requires records. But I didn’t play it anymore, not even when the night got loud. I had a new habit instead: when the old ache came trotting up like a dog that refuses to learn the new name you gave it, I’d open that drawer, touch the flash drive for a second, and then close the drawer again, choosing the living room, the basil, the person in the other room who said “Grow” to plants and people with the same steady faith.

There’s no big lesson here that isn’t a small one dressed in capital letters. If there is one, it’s this: the truth costs what it costs, but it buys you your life back at full price. You can hold it in your hands in a booth at a 24-hour diner and think you’ll never stop shaking. You can use it like a blade and cut the rope that would have dragged you into a future where you pretended not to hate yourself. You can put it in a drawer and let it cool.

People sometimes ask if I’d do it again—the ballroom, the ten seconds. They ask it like they’re trying on the thought of their own private revolutions. I tell them there were a thousand other ways to end a wedding. I tell them none of them would have worked for me. I tell them I didn’t want a quiet ending that could be revised later by people who lie professionally and personally.

What I don’t always say is that those ten seconds made room for everything after. The diner. The boxes. The gym. The letter. The gallery. The basil. The risotto. The Tuesday. Even the knock on the door at 8:15 a.m. taught me something: that some people weaponize propriety because they don’t want to look at themselves under good lighting.

By the time summer leaned over the windowsill and asked if we wanted to come out and play, I could walk past a mirror and not wince at the man looking back. I could stand in a ballroom for a coworker’s reception—yes, a ballroom, because life has a sense of humor—and not taste iron in the back of my throat. When the screen flickered to life and baby pictures scrolled across it in a parade of soft foreheads and terrible haircuts, I clapped with everyone else.

The couple danced. The toasts wobbled. The cake cut perfectly even because someone in the kitchen cared about right angles. I hugged my coworker, and he whispered that love is terrifying and worth it and I nodded, because both were true. I walked to the bar for a seltzer with lime and felt the ordinary buoyancy of rooms designed for celebration.

On the way out, I texted Mara: Bring anything from the store? She wrote back: Just you. Then, a beat later: And maybe basil. Ours is stubborn.

I looked up at the moon, which didn’t care and also cared, and I laughed. I drove home by a route that passed the old hotel, not out of pilgrimage but because it was on the way. Kalin’s car wasn’t there. Of course it wasn’t. That was someone else’s scene, played out to its ragged end. Mine was the soft lamp in a window two turns further on, the key that turned a lock with no drama whatsoever, the sound of a basil leaf being plucked, reverent and ordinary, into a bowl.

And that, as clear as endings get, was that.

News

At our wedding, his childhood sweetheart announced that he had helped her shave down there CH2

Part I The first knock wasn’t a knock so much as a drumroll—fast, jittery, the kind of sound you hear…

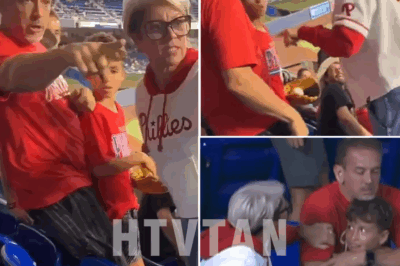

FAMILY SPEAKS OUT AFTER WOMAN IN PHILLIES HOODIE SNATCHES HOME RUN BALL FROM CHILD AT CITIZENS BANK PARK, SPARKING NATIONAL OUTRAGE, INTERNET SLEUTHING, AND DEBATES OVER FAIRNESS AND DECENCY IN AMERICA’S PASTIME

When fans file into Citizens Bank Park to watch the Philadelphia Phillies, they expect a night of excitement, maybe a…

BREAKING: WOMAN DUBBED ‘PHILLIES KAREN’ SPARKS OUTRAGE AFTER SNATCHING HOME RUN BALL FROM CHILD DURING PHILLIES GAME, PROMPTING CALLS FOR CONSEQUENCES AND IGNITING A NATIONWIDE DEBATE OVER FAIRNESS AND DECENCY IN SPORTS CH2

Baseball has long been considered America’s pastime, an arena where family traditions, neighborhood pride, and generational memories converge. It is…

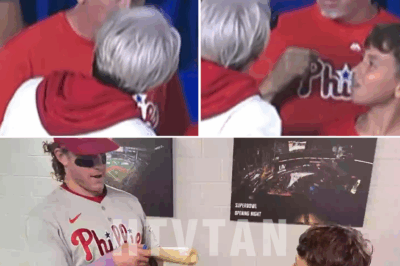

WHO IS THE MYSTERIOUS WOMAN DUBBED ‘PHILLIES KAREN’ WHO SNATCHED A BALL FROM A CHILD AT A PHILLIES GAME, NOW BEING OFFERED $5,000 IF SHE RETURNS IT WITH AN APOLOGY CH2

In a broadcast moment charged with political gravity, Fox News contributor Jessica Tarlov found herself unusually quiet on the day…

SHE GRABBED THE BALL, THE CROWD ERUPTED, AND NOW THE INTERNET IS CHASING THE WRONG WOMAN IN A PHILLIES HOODIE, SPARKING CONFUSION, OUTRAGE, AND A MYSTERY THAT WON’T DI/E CH2

Tarlov Was “Silenced” by Fox News When Trump’s $90 Billion Deal Was Signed On a day when national attention was…

Make Space in Our Home—My Parents Are Moving In,” My Husband Declared Without Warning. CH2

Emily was at her desk when a knock sounded at the study door. Oliver stepped inside, glancing around the familiar…

End of content

No more pages to load