Part One

The first time I saw the hotel charge, I told myself a story.

It was a Tuesday, ugly with rain, the kind that turns Charlotte streets into quicksilver and makes everyone’s patience evaporate. I was reconciling our AmEx in the home office—my little kingdom with the vintage campaign posters and a corkboard layered in color-coded sticky notes—half-listening to a podcast about branding and boiling a pot of pasta for the girls. Madison and McKenzie, seven, still thought spaghetti night meant magic.

There it was on the PDF: Hotel Tryon — $347.89 at 2:15 p.m. on October 18. Two blocks from the Downtown Athletic Club.

“Sterling?” I called, casual as a whisper. “You have a client dinner today?”

“Inventory run,” he shouted back from the garage, where he likes to tinker with nothing. “Might grab a late lunch after. Love you!”

I looked at the clock. 2:17 p.m.

He’d always been a smooth liar. It’s a form of artisanal craftsmanship with Sterling Mitchell—subtle, bespoke, tailored to fit. He’s the kind of man who can tell you a story with his eyes and make you grateful to be included. When we met, he turned that skill on me. For years, I called it charm.

That day, I called Daniel.

Every woman who says, “I never thought I’d…” is telling the truth and a lie at the same time. We never think we’ll hire a private investigator, and yet we keep cardholders like Daniel Reed in business. Former CMPD, now independent, comes recommended by the kind of women who drink rosé at noon on a Thursday and know exactly how long a subpoena takes. His voicemail was unremarkable; his call back, punctual.

“You want surveillance or verification?” he asked, voice like granite worn smooth by use.

“Verification,” I said. “I already have the feeling.”

He didn’t need more. “I’ll send an engagement letter. You’ll never see me.”

By Friday, I had photographs. Saturday, I had a timeline. Sunday, I had something close to a religion: Evidence.

Lunch dates masquerading as dealership meetings. Hotel Tryon. Ritz Charlotte. Credit card pings like Morse code, sending messages from corners of the city where love lives in the daylight if you don’t recognize it. And her—Sloan—the nurse, twenty-eight, Presbyterian Hospital scrubs, freckles, an optimism you can only keep if you’ve never been asked to apologize for joy. Sterling’s “work stress” had a pulse, a schedule, a room key.

And then there was Reagan.

My best friend, thirteen years woven into the fabric of my life: first apartments, bachelorette weekends, the births of our girls, casseroles delivered with laughs and the good kind of gossip. Reagan of the gym selfies and the “you’re a queen” pep talks, the woman who could talk a rumor out of being mean just by sprinkling it with sparkle. Reagan of the oat-milk vanilla latte and compressed lips at anyone else’s success. Reagan, who texted me the second she sensed my silence.

“Hey girl, coffee? I have the WILDEST story about the new trainer.”

“Absolutely,” I typed, and put my phone down. I had to stop my hands from shaking not because I was afraid of what she’d say but because I didn’t trust myself not to scream with laughter at the predictability of it all.

Amal’s French Bakery on Park Road is that brand of adorable that looks like a movie set. Reagan arrived in athleisure that cost as much as a mortgage payment, hair in a ponytail that could have hosted a small bird. “You will die,” she said, sliding into the chair, conspiratorial.

“Tell me everything,” I said, and hit record under the table. It wasn’t illegal—the law and I are acquainted—and it was necessary. Sterling and Reagan had coached me so carefully for so long that I needed the sound of their own voices to anchor me to reality when they tried to unmoor me later.

She talked. She always talks. “Sterling’s so stressed,” she cooed. “You know how demanding his job is getting. You should give him more space. Guy time. He works so hard for you and the girls.” She squeezed my hand, a gesture calibrated for cameras and mothers-in-law, and smiled like a sunrise.

“Such a good friend,” I said, and pressed harder on the record button as if permanence were a pressure point I could hold.

Once you learn to stop listening to what people say and start listening to what they do, truth stands up from the couch and stretches its arms. Over the next two weeks, I became a new species of creature—animal eyes but analyst mind. I started collecting. Not rage; data.

Reagan’s Instagram story on October 22: SouthPark Mall, new leggings! #grind at 3:11 p.m. Sterling’s BMW geofenced at SouthPark for three hours. October 25: Reagan’s “cozy night in” with a glass of pinot—the reflection in the curve of the glass showed two blurred shapes, and all at once I wanted to send her a tripod. November 3: Sterling “in Greensboro for a training seminar,” a Ritz receipt and a photo of a room service tray for two. I built spreadsheets that would make an FBI intern cry—columns for time, location, source, cross-reference. The thing about social media is it’s never a confession until someone knows how to read it.

I could have confronted them right then, in my kitchen, with spaghetti boiling over and a cat weaving between my ankles. I could have screamed. I like to imagine I did that in some alternate universe—broke a plate, hurled a curse, gave Sterling a romantic comedy slap. But this universe had better lighting.

Instead, I planned.

Thanksgiving was six weeks out. In our house, it’s a tradition, not a holiday: both sets of parents, Reagan and her mother, kids underfoot, my Waterford china gleaming like a sermon. I’ve made a career out of designing campaigns that change minds. I’ve put entire product launches on a single image. I’ve turned a brand’s quarter around with a sentence. Surely I could build one unforgettable night that would collapse a liar’s decade.

I booked the videographer first, under my maiden name. James specializes in weddings and “day-in-the-life” family shoots—the kind where toddlers smear frosting on camera, dads pretend to love dancing, and mothers cry in slow motion. I told him I wanted to memorialize “five years of hosting and all the generations together.” He practically stood at attention.

“Multiple cameras, please,” I said. “Wireless lav mics for speech clarity. Warm tones.”

“Love that,” he said. “The golden-hour look.”

“Yes,” I said. “Golden.”

I called Sterling’s favorite restaurant—the one he took Sloan to three times in the past month (receipts don’t lie, they just report). I ordered the exact dishes he always bragged about in a tone that had always made me homicidal: braised short ribs and truffle potatoes because some men never stop shopping for status with a fork. I bought Reagan’s favorite tart from Dean & DeLuca and a bottle of Dom because if I was going to scorch the earth, I wanted to do it under perfect bubbles.

And then I did what people like my mother would call “petty” and what I, as a marketer, call stagecraft: I wrote a script.

I opened Keynote and created a deck titled GRATITUDE in a font so tasteful even Patricia, my mother-in-law, would approve. Slide one: The girls’ first steps. Slide two: Beach vacations that had to be fun because the photos were. Slide three: Sterling teaching Madison to ride a bike; his hands outstretched, that look on his face like he’d invented bikes. Interspersed: my parents dancing at their fortieth; Robert accidentally catching a fish that immediately escaped; Carol bringing her cornbread stuffing like church.

And then the turn. It’s all pacing. Marie Kondo says thank your old stuff before you throw it out; I say make your audience cry before you make them watch a public hanging. Slide twelve: The People Who Make Our Life Possible—Sterling’s company logo, Reagan’s “life coaching” brand. My recorded voice in the background, warm and earnest as a Pinterest quote. “We are so lucky,” I wrote and meant, in a way, every word.

Then: Exhibits. Receipts, credit card statements, location data, screenshots. Reagan’s audio—“He needs outlets, you know…”. Sterling’s texts to Sloan—names blurred for the girls’ sake but the nouns unavoidable. A highlight reel of two years of betrayal, cut like a prosecution’s closing statement. I built in pauses I knew would be filled with gasps.

I created three burner accounts—professional headshots, bios, convincingly banal posts—and followed Reagan’s clients, Sloan’s colleagues, Sterling’s coworkers. A week before Thanksgiving, those accounts started liking articles about workplace ethics and relationships. Not a whisper; a suggestion. I wasn’t aiming to ruin with rumor. I was building a context in which truth could stand by itself and be believed.

Two days before the dinner, I uploaded the finished forty-seven minutes to a private hosting service. Professional edit. Clean audio. Every file backed up—cloud, two drives, a safety deposit box. I printed hard copies of policy documents: Presbyterian Hospital’s social media rules; BMW’s ethics codes. I highlighted the sections about relationships that impact workplace dynamics and misuse of company property. I breathed. Slowly. In. Out. In.

Thanksgiving morning arrived crisp and earnest. Lake Norman air has a way of making even stubborn hearts believe they can start over. I woke at five and brewed coffee strong enough to change a vote. The turkey went into the oven on schedule. The girls thundered down in matching burgundy dresses. Sterling came down in the Duke sweatshirt Reagan gave him last December and kissed my cheek, domestic as a commercial.

“Smells incredible,” he said, and I said, “This year is special,” and meant it.

By eleven, my parents had arrived—Mom with the green bean casserole; Dad with a bottle of wine that cost more than our electric bill because he thinks generosity is a sport. At eleven-thirty, Patricia entered my kitchen with her annual inspection gaze and a Tupperware of gravy as if mine needed backup. Robert made himself a beer flight on the sofa and adjusted the football volume to male. Normal is a thing you can still recognize after it’s over; it’s just harder to trust while it’s happening.

At noon, Reagan floated in, polished and perfect, a camel sweater dress and knee-high boots, perfume that has paid her rent twice over in the last year. She hugged me like nothing in the world had ever disappointed either of us, handed me Dom with a conspirator’s wink, and kissed my cheek for the cameras.

“We have so much to celebrate,” she said. “We certainly do,” I said, and watched her drift to the couch and sit beside my husband like the punchline she never got tired of.

By one, Carol had arrived with her quiet grace and a bouquet that made my dining room look like hope. She doesn’t deserve this, I thought, and then corrected myself: She doesn’t, but the guilt was mine to carry and put down later, in private.

At two-thirty, we gathered around my grandmother’s Waterford. Sterling carved with ceremonial pride. The girls asked for extra mac. Mom complimented the sweet potatoes. Robert told his Navy story. The world made the sounds families make when they think they’re safe.

“So.” My mother smiled at me over cranberry sauce. “Harlo, how’s the marketing business?”

“Busy,” I said, and spooned mashed potatoes with a hand that did not shake. “I’ve been working on a comprehensive campaign about truth in relationships. How people present themselves versus reality. It’s been… eye-opening research.”

Forks stalled. For a second, the room failed to pretend. Patricia’s mouth started to make a shape it uses for criticism; she put it away.

“That sounds fascinating,” she said, brittle. “Data tells stories people never intend to share,” I said, and smiled with all my teeth.

At four, dessert appeared: apple pie, pumpkin cheesecake, the chocolate tart from Dean & DeLuca Reagan could never stop talking about. James, the “family friend,” asked from the doorway, “Ready to start?”

“Perfect timing,” I said, untying my apron. “Everyone—living room, please. I’ve prepared a little gratitude presentation.”

Sterling looked up from adjusting his father’s footrest. “What video?”

“It’s a surprise,” I said, and handed him a beer. “Something special I’ve been working on. About our family. Our friendships.”

Reagan turned, smile luminous. “Harlo, you always think of the sweetest ideas.”

“I do try,” I said. “I believe in showing appreciation for the people who shape our lives.”

We arranged ourselves in the living room the way families always do: parents in favorite chairs, kids clumped at the edges, mothers practicing expressions they can live with on camera. James had placed three cameras on tripods. The light warmed our faces. If I’d had a rehearsal dinner, it would’ve felt like this. Sterling helped seat Patricia. Reagan sat beside my mother and touched her hand with faux daughter-in-law intimacy that made my stomach hard.

I stood by the mantel and held the remote the way a magician holds a deck—confident, kind.

“Before we start,” I said, “I want to say I’m grateful for all of you. For love. For support. For loyalty.” Murmurs. Smiles. A glisten at the corner of my mother’s eye.

“This presentation,” I continued, “is about the people who make our life possible. The relationships that define us. The bonds we treasure most. Some of what you’re about to see might surprise you, but I believe in honesty above everything—in showing people exactly who they really are.”

Sterling shifted. Reagan’s smile flickered like a bad connection. I pressed play.

Nostalgia first: babies crawling, beach sunsets, cupcakes, a montage engineered to soften even the most suspicious heart. At three minutes, my mother was dabbing tears. Sterling beamed at Bike Lesson Sterling. Reagan leaned back, satisfied, one hand smoothing her sweater like a cat.

At four minutes and thirty-seven seconds, the music dipped.

“Now,” my voice said—a pleasant narrator—“let’s talk about the relationships that have truly shaped us. The people who have worked behind the scenes to create the life we’re living.”

Sterling’s headshot appeared, then his company logo. Laughter. Pride. “For instance,” my voice cooed, “Sterling’s incredible work ethic—like last October 18, when he worked inventory so hard he forgot to mention the three-hour meeting at Hotel Tryon.”

On screen: the cropped AmEx statement, highlighted, zoomed. He went white the way men go white when the blood leaves their stories first.

“Or October 22,” my voice went on, “when that dealership training ran so late he missed dinner.” Parking receipt. SouthPark. Time stamp overlaid on Reagan’s story.

And then November 3: Ritz-Carlton, two nights, room for two. “Remember, honey?” my voice asked sweetly. “Greensboro seminar?”

Sterling stood. “Harlo, what is this?”

“Sit down, sweetheart,” I said without looking at him. “We’re just getting started.”

Patricia made a sound like glass cracking. Robert muted the game.

“Now,” my voice said, cheerful and lethal, “let’s talk about Reagan Palmer, my dearest friend. The woman who has been so supportive of our marriage.”

Her Christmas-party photo slid onto the screen—perfect teeth, perfect hair. “Reagan has given such helpful marriage advice,” I said, and tapped play again.

Her voice filled our house, bright and cruel in its innocence. He needs guy time… give him more space… you should focus on work… Sterling needs outlets… Then me: You’re such a good friend, Reagan. Then her: I just want you both to be happy. My mother’s hand flew to her mouth. Carol went rigid.

Reagan shot up. “Harlo, you recorded—”

“Oh, that’s nothing,” I said, gaze like iron. “Compared to what Sterling and Sloan recorded.”

On screen: blurred but obvious screenshots, heart emojis, time stamps, selfies taken in hospital scrubs under fluorescent lights that make no one beautiful. “Two years,” my voice said, conversational. “Two years of messages. Two years of hotel receipts. Two years of work stress.”

Sterling’s father stood, red as a boiled lobster. “What in God’s name—”

“Patience, Robert,” I said, and clicked to the next slide. “Now the best part—Reagan’s strategy.”

A message I’d almost admired appeared—Sloan’s sweet, but she doesn’t understand you like I do. When you’re ready to be with someone who truly gets you, I’ll be here. Until then, I’ll keep Harlo busy with work. Reagan’s mother whispered, “Reagan?” so softly it felt like a prayer.

“It means,” I said, turning at last to face the room, “my best friend has been in love with my husband for years. It means she has been actively helping him cheat while waiting for her turn. It means my thirteen-year friendship was a mask for the longest con I’ve ever seen.”

Reagan started to cry, mascara carving black rivers down her perfect. “You don’t understand—”

“Oh, I understand,” I said. “You thought he’d get bored of his nurse and move to his coach. You hedged your bet.”

Click. Presbyterian policy on the screen, Section 4.3 and 5.2 highlighted in yellow. “Unfortunate,” my voice said, “that Sloan’s social media is public. Unfortunate that Presbyterian has strict guidelines about relationships that create workplace drama. Unfortunate that I filed a complaint yesterday.”

Sterling found his voice, which had gone hoarse with disbelief. “Harlo, please—my job—”

“BMW received a package this morning,” I said. “Company cars are for business, not romance. You signed that code.”

He fell back into the couch like a man who’d discovered gravity.

The room became noise: Robert shouting, Patricia sobbing, Carol wiping tears with paper because cloth couldn’t handle it, my parents sitting like statues in a museum where the sculptures had been given terrible news. Through it all, I stood with the remote at my side and the calm of a person whose work has shipped and now belongs to the world.

“What do you want?” Sterling choked finally. “What will it take to fix this?”

I smiled for the first time all day. It didn’t feel like victory. It felt like air.

“Fix this?” I said. “Oh, honey. This isn’t something you fix. This is something you live with.”

James’s little red recording lights blinked like tiny, honest hearts, capturing every flinch and denial, every silence that told the truth better than a confession could. Upstairs, the girls’ laughter drifted down the staircase, pure as rain.

And that was the moment I knew: I had already won. Not because I had humiliated two people who deserved it, but because I had taken back the narrative. I had stopped being an extra and written myself into the scene as lead—and director.

Thanksgiving ended. The turkey cooled. The cameras shut down. People left in waves: parents first, then shock, then Reagan with Carol’s hand on her elbow and a face shaped like regret. Sterling slept on the couch, because that’s what men do when their lives break in a living room.

I washed dishes until midnight, hands in hot water, the smell of lemon cutting through the day like a line. When I finished, I took the USB drive that held the presentation and slid it into the safety deposit envelope I kept in the desk drawer, then flicked off the dining room light. The chandelier made one last little music as it cooled—tinny, beautiful, final.

Six weeks later I would be in a new home office overlooking Lake Norman, the girls would be okay, and I would run a company that turns betrayal into proof. Sterling would discover that used car lots still expect honesty on the lot even if you’ve run out at home. Reagan would be in Atlanta, selling sessions at a corporate gym to women who hadn’t yet heard her name said like a warning. Sloan would be learning the difference between a job and a license.

But that night, all I did was sleep.

The next morning, I woke up to a house that had finally told the truth.

Part Two

The morning after Thanksgiving, my house smelled like nutmeg, lemon soap, and the metallic after-scent of adrenaline. I brewed coffee so dark it could file its own affidavit and stood in the kitchen listening to the refrigerator hum like a witness who had seen everything and would say nothing.

My phone lay face down on the counter because light was too much. When I finally flipped it over, the screen bloomed with the night’s unanswered harvest—texts, missed calls, voicemails. Sterling, of course. 20 from Reagan. Two from Carol, one from my mother, a long one from Patricia that began with Harlo, I don’t understand and dissolved into tears in audio form. Three unknown numbers that I suspected belonged to versions of damage control.

I let the coffee anchor me. Then I began.

Sterling first:

Sterling: We need to talk.

Sterling: Please don’t do anything rash.

Sterling: I’m sorry. I never meant to hurt you.

Sterling: I love you. I love our family.

Sterling: I’ll end it today.

Sterling: Please call me. Please.

Sterling: I don’t know why you did that in front of our parents. That was cruel.

Sterling: We can fix this.

Cruel is a fascinating word. It expands and contracts depending on who’s holding it.

Reagan’s read like the stages of a textbook:

Reagan: Harlo I am shaking.

Reagan: I did not do anything! You twisted things.

Reagan: Okay I did some things but not like THAT.

Reagan: I love you. You’re my sister.

Reagan: I’m so sorry. Can we please talk somewhere private?

Reagan: You ruined my business. Why would you involve my mother?

Reagan: You’re not who I thought you were.

The unknown numbers were more efficient.

Unknown: Ms. Bennett, this is HR at Presbyterian. We received a submission yesterday and would like to clarify some items and collect originals for our file.

Unknown: Ms. Bennett, this is BMW Group Compliance. Please return our call regarding a report received in our ethics inbox.

I put the phone down and smiled, not because I was happy—happy was a room I had moved out of—but because the machine had begun to do what machines do: process.

Madison padded in, hair sun-snarled, pajamas trailing the imaginary dirt of dreams. “Can we have pie for breakfast?” she asked, because she is seven and believes in joy like it’s a muscle.

“We can negotiate,” I said, and poured her milk. McKenzie thundered down an instant later, all knees and opinions. They ate pecan crumbs with solemnity while I fried eggs and made toast, and in those ten minutes I remembered: normal exists not in the absence of disaster but in the presence of small routines.

Sterling didn’t come down. He had slept on the couch, a pile of man in the corner, and at some raw hour he must have taken his keys and gone because his car was missing from the drive. He left a note on the counter—I’m so sorry. I’ll fix this. If I had been the woman I was a year ago, I would have traced the letters for evidence of sincerity. The woman I had become folded the note in half and slid it into a folder labeled Dissolution.

By ten, I’d called my parents to assure them the girls were fine and me more than fine. Mom said she’d come over with soup anyway because soup is how Southern women apologize for not choosing your husband with more care. Dad told me to call if I wanted him to be present “in any configuration,” a phrase I loved for its lawyerly vagueness. Patricia left a second voicemail wanting to “understand the context,” as if context were a mercy the evidence had denied her. Carol’s text was the one that pierced: I am so sorry for what my daughter did.

I texted her back: Thank you for coming. I know last night was hard. Please take care of yourself. That was all I owed and everything I could offer.

Then I called the numbers that mattered.

Presbyterian’s HR rep had an efficient voice that made me want to straighten my posture. “Ms. Bennett, we’re conducting an internal review under Sections 4.3 and 5.2 of our policy. We appreciate the documentation. We’ll need originals or certified copies of the screenshots, the hotel receipts, and any additional timestamps connecting Ms. Caldwell’s shifts to the encounters referenced.”

“I have backups,” I said. “And timestamps from my investigator that cross-reference hospital badge logs.”

A pause that wasn’t surprise, just professional respect. “Then you understand what we need. We’ll arrange a secure delivery this afternoon.”

BMW Group Compliance wanted slightly different things. “We’re obligated to review any allegation regarding misuse of company property, including vehicles, expense accounts, and time records,” the analyst recited. “We appreciate your submission. May we ask whether Mr. Mitchell was aware of your intentions to file?”

“He is aware of his behavior,” I said. “Which has been documented thoroughly.”

“Understood,” she said, and I believed she did. “You’ll receive a formal acknowledgment and confidentiality notice. You may be asked to make a statement.”

“Happy to do so,” I replied. Happy was the wrong word. Ready was correct.

At noon I met with an attorney, a woman named Escobar recommended by a client whose divorce had been swift and quiet because she’d played a long game like me. Escobar’s office had plants that thrived without sunlight and a view of a parking lot, which somehow made me trust her more.

“Most of my work is preventive medicine,” she said after she scanned my binder and Daniel’s summary. “I advise people on how not to bleed out.”

“Am I bleeding?” I asked.

“Not anymore,” she said, flipping to the tab I’d labeled Financials. “With documentation like this, judges tend to like stipulations. We file, we negotiate, we keep filings dry. We put the kids first. You get the house; it’s yours premarriage. We pursue dissipation if you want to recoup. Primary custody with a schedule Mr. Mitchell can keep with his new employment.”

“He still works at BMW,” I said.

“For now,” she said, and slid me a list titled To Do. At the top: Open a separate bank account; redirect pay; freeze joint line of credit. Below that: Therapist referrals for the girls; script for age-appropriate disclosure. At the bottom, circled: No private confrontations. Everything in writing.

“What about… him?” I asked, and surprised myself by not using Sterling’s name.

“If he hires counsel with a brain, they’ll settle,” Escobar said. “If not, we litigate. But with this?” She tapped the evidence again. “He’ll settle.”

We filed Monday morning at 9:02 because the system didn’t open at 9:00 on the dot. Escobar e-filed and had a process server in Sterling’s lobby before lunch. He texted as soon as the envelope hit his hand: I can’t believe you’re doing this. It’s amazing, the passive voice men use when consequences arrive.

That afternoon, BMW called back. The tone had changed. “Ms. Bennett, your report has been escalated. Mr. Mitchell’s access to company vehicles has been suspended pending review.” I thanked them and hung up. Sterling texted again—the raw yelling type their fingers use when their mouths have lost an audience.

Sterling: You’re ruining my career.

Sterling: How could you go to my JOB?

Sterling: We agreed our marriage issues were separate.

Sterling: Please retract. I’ll quit, I’ll do ANYTHING.

Men who have bullied reality into compliance for years talk to you like you can be bullied into forgiving them. It’s almost sweet, if you squint through a sociologist’s lens.

Reagan showed up Wednesday with a face like a movie’s third act. Carol was with her, a mother being a mother even when the child is thirty-four and has set her life on fire with perfect makeup.

“Five minutes,” Reagan begged at the door. “Please. Privately.”

She had given me a decade of uninvited advice. I gave myself five minutes of merciful exposure therapy.

In the kitchen, she shook, whether from caffeine or fear or finally touching the sharp edge of truth I couldn’t say. “I didn’t— It wasn’t— I never meant—” she stuttered.

“You always meant,” I said gently. “Maybe not the first day. But the hundredth? The five-hundredth?”

Her mouth trembled. “I love you,” she said, the high note in her voice hinting at the practiced nature of the statement.

“No,” I said. “You loved proximity. To my life. To my husband. To a version of yourself you only felt near us.”

She flinched. Carol began to cry. “Harlo, please. She is my daughter. She is a fool, but she is my daughter.”

“I know,” I said. “I don’t want to punish you, Carol. I want clarity. And distance.”

“People are talking,” Reagan whispered. “I lost six clients this morning.”

“Then you have time to reflect,” I said. “Here are some boundaries: you do not contact my family. You do not contact my children. You send any legal communication through counsel if you end up needing to. You do not try to fix me.”

A tiny laugh broke out of her chest at that last line, a reflex from our old life where she was the fixer and I was the fixed. “You are different,” she said, almost with wonder.

“I am the same,” I replied. “Just unwilling to perform.”

They left. In the hall mirror, I looked older by a year and more like myself by ten.

Presbyterian’s letter arrived the following Tuesday—administrative leave pending investigation. Then, two weeks later, termination for cause. The state nursing board opened a file; HIPAA violations have both letters and teeth. Sloan emailed from a free account, subject line A Conversation. I forwarded it to HR and did not respond.

BMW’s letter came faster: termination for cause after an internal review of vehicle logs, calendar discrepancies, and expense reports. There’s a tone corporations use when they know lawyers will be the next readers; it’s as bleached of emotion as an OR. Sterling texted once after that: I can’t believe you did this to me. Then, later, a small unpunctuated i’m sorry that made me ache in a place I didn’t know I had left.

Escobar steered the divorce the way a river moves a leaf—patient, relentless, unhindered by the leaf’s opinion. We stipulated custody, added a clause about introductions to new partners requiring six months and therapist approval. We folded in alimony numbers that felt more like math than revenge. We insisted on a non-disparagement clause with teeth because my girls will not grow up in a world where tall men lie about their mother to feel less short.

The girls and I saw a child therapist on a Wednesday afternoon in an office decorated with puppets that made me want to tell someone a story and a white noise machine that suggested all stories could be kind if told slowly. We worked on a simple script: Sometimes adults make choices that hurt people, and then families have to change shape. Madison asked if our family would still be “real.” I told her yes. McKenzie asked if we could still have spaghetti night. I told her yes, and almost smiled for the first time all week.

News travels strangely in Charlotte: partly on the internet, partly at Publix, partly at barre class. I didn’t post anything; I didn’t need to. But I did write a short note for my circle: We’re separating. The girls are okay. I’m okay. Please keep their names out of your conversations and put soup on my porch if you must put something somewhere.

And then the calls started. It took three weeks, just like the rumor cycle I can plot in my sleep.

“Hi,” a woman said, voice low in the way that means a husband is home. “You don’t know me, but you helped a friend of mine. I need… I don’t know what I need, exactly.”

“You need your reality back,” I said. “We can do that.”

In January, I registered Truth & Consequences Digital Consulting, LLC. My lawyer raised an eyebrow at the name; I told her it tested well in focus groups of women who have been told for years that they were crazy. I rented a small office with a view of a parking lot because good work doesn’t require a skyline. I wrote an intake form that asked questions no one ever asked me when I was losing my mind: What does your body feel like when you think about this? Where do you want to be standing when the truth comes out? Do you want the quiet outcome or the loud one?

I built rules. No illegal anything. No deepfakes, no spoofing, no hacking, no entrapment. Only already-there truth gathered clean and presented clearly. No children in the blast radius. If a client wanted a spectacle for spectacle’s sake, I declined. If a client wanted to “win” by becoming the very thing she hated, I referred her to a therapist. I created packages named like case studies: Verification, Documentation, Disclosure. The last one came with two options: Therapeutic Exposure—private, controlled, witnesses chosen; and Strategic Exposure—public, layered, consequences mapped. I never called it revenge. I called it restoration.

The first client was from Cornelius, exactly as the rumor predicted. Her husband’s phone location history had been mysteriously “erased” (men think cloud backups exist to serve their convenience, not their undoing). She wanted to be sure before she set her life on fire. We confirmed. We plotted a disclosure that involved her pastor, his sister, and a lawyer in the same room so he couldn’t rewrite their history while she cried. It worked. She sent me a note two weeks later that said, I slept. That’s all I wanted.

The second client asked for a spectacle. I refused. She cried, then thanked me. The third wanted receipts for a court date. We color-coded time and money and turned it into a timeline even a skeptical judge could love.

Between meetings, I put boxes into other boxes. I staged the house in Ballantyne and sold it in eight days to a family with one toddler and another fixture of suburban hope on the way. In February, we moved to a glass-edged townhouse near Lake Norman with light that forgave and a kitchen too modern for casseroles. The girls made forts of boxes and renamed rooms. The view of the water at 7 a.m. looked like God had designed it to apologize for men.

Sterling’s life adjusted downward to match his choices. He took a job on Independence Boulevard selling cars cut from lives like his: shiny, overpriced, needing too much attention. He was good at it, I think; he’s always been good at making strangers believe things. He showed up on time for supervised visitation, brought craft kits, learned how to braid badly. He didn’t bring his phone to dinner anymore. Sometimes that is growth; sometimes it’s a court order. Both can be true.

Reagan’s fall was artless. Screenshots circulated in the Charlotte fitness community, because of course they did. Clients dropped. The certification board opened an ethics review. Her “authenticity” posts drew comments that used to be hers for other women. In January she texted me a link to a listing in Atlanta with the caption fresh start. I did not respond. Carol mailed the girls Christmas cards with glitter and a check. I deposited the check into their 529s and threw away enough glitter to enter a crime scene.

Sloan… I don’t think about Sloan much. That’s a lie. I think about her when my temper wants to become a personality trait. She was a nurse who broke her own rules and her patients’ privacy to coordinate trysts. She lost her job and maybe her license. She moved to Gastonia, if the grapevine can be believed, and took a medical assistant position that pays less than Sterling’s new salary. If I say I do not feel satisfaction, I am making a saint of myself I have no interest in being. What I feel is equilibrium. The world leveled.

The girls adjusted the way children do—with questions that feel like lasers and forgiveness that makes you reconsider theology. Madison took to piano with a seriousness that made me rethink screen time; McKenzie ran her energy into a travel soccer team and slept like a child again. They learned words like schedule and terms like two-household family and asked for both mac-and-cheese recipes to be in the new kitchen.

One afternoon in March, after a day of intake calls and a lunch of something green I would’ve laughed at ten years ago, I sat on the balcony and looked out at the lake. My laptop hummed with a new client’s documents. A gull skimmed the water and made me consider the theology thing again. My phone buzzed.

Unknown: You don’t know me. I’m the junior trainer who used to work under Reagan. Thank you for last Thanksgiving. Some of us learned that enabling is participation, and we opted out.

I typed and deleted six responses before landing on the one that didn’t spin itself.

Me: Take care of yourself. The rest follows.

The sun laid a gold bar across the water. I thought about the presentation again, about the way the word GRATITUDE looked huge on the wall before it became a weapon. That’s the thing about truth: it doesn’t ask for a marketing budget. It asks for timing.

Three days later, I drove into uptown to speak at a small conference that had been rebranded into an Empowerment Summit because Charlotte loves an event that sounds like a yoga pose. They’d asked me to talk about branding, but when the organizer called the week before, she asked if I’d consider shifting the topic.

“We heard,” she said delicately, “about your… Thanksgiving.”

“You want that story,” I said.

“We want women to hear that they can walk out of a burning house without smelling like smoke,” she replied, and I liked her for the way she didn’t apologize for wanting a story.

I titled the talk Turning Betrayal into a Brief and built a deck that stole shamelessly from the gratitude presentation’s skeleton. I cut the messy parts—blurred faces, redacted names. I kept the bones: signs, documentation, strategy, execution, and the ethics of not becoming what you expose. When I finished, women lined up not for selfies but for sentences they needed to say out loud to a stranger to make them true. I listened. I handed out cards that said We believe you, and we can prove it. I went home to my girls.

On the way, I passed the BMW dealership where Sterling used to collect signatures like trophies. The new banner read SPRING EVENT in a font that looked too cheerful for the weather. I kept driving. On Independence Boulevard, a row of used car lots gleamed under light towers. I wondered if Sterling had become good at saying honest numbers when a father with a toddler on his hip asked him what was under the hood. I hoped so. For the father.

That night, after bedtime songs and a third cup of water and the standard list of follow-up questions children invent to delay sleep, I stood in the doorway and watched the girls breathe. In the glow of the nightlight shaped like a moon, I promised them a quiet I could keep: that their home would never again be a stage for adults who demand applause.

Downstairs, I opened my laptop to a new inquiry. A subject line: I’m not crazy, right? An attachment: a screenshot of a husband’s text, timestamped, a lie trying to dress itself in the suit of truth.

I took a breath and wrote back the sentence I wish someone had written to me on the first night I felt my body go numb: You’re not crazy. You’re correct. Let’s get you the proof you deserve and a plan that protects what matters.

Send.

I closed the computer and poured a glass of something that promised oak and delivered warmth. On the balcony, Lake Norman gasped once under a breeze and settled. Detective—the neighborhood cat determined to make my house his—leapt onto my lap and kneaded my thigh like dough. For the first time in months, I let myself think about a future chapter with fewer footnotes.

When Sterling texted the next day to say he had found a two-bedroom near the airport with a window that got morning light just right for the girls to color in, I replied with a thumbs-up and then, after a moment, Thank you for finding a place they’ll feel safe. He wrote back I’m trying. It was the first true thing he’d said to me in a long time.

The six weeks after Thanksgiving taught me a language I didn’t know I could speak: directness without fury, boundaries without apology, consequence without theatrics. I built a business that turned that language into a service. I built a home where the only performance was a seven-year-old’s piano recital.

The truth didn’t need a campaign. It needed a presentation and a woman who’d stopped treating her empathy like an unpaid job.

And because of all that, I slept.

Part Three

The email subject line was a whisper: I’m not crazy. Please help.

She arrived on a Tuesday with a tote bag and the stiff posture of a person holding herself together like a stack of dishes. Mid-thirties, wedding set still on, hair hastily smoothed in the car. She sat in the chair across from my desk and gripped the canvas straps like they were reins.

“I’m Lydia,” she said. “My husband is a surgeon. Noah Hart. We’ve been married eleven years. Two boys—ten and twelve. I need to know if I’m wrong.”

People who open that way aren’t wrong. They’re polite. I slid a glass of water across the desk and nodded for her to continue.

“He’s on call a lot,” she said. “Or says he is. And his best friend since residency—Paige—she runs the foundation attached to his practice. They’re always together for ‘donor dinners’ and ‘strategy meetings.’” She almost laughed at her own air quotes. “I sound like a cliché.”

“You sound like a person who has noticed things,” I said. “That’s different.”

She exhaled a breath she might have been holding for a year. “I don’t want a circus,” she said quickly. “I watched a TikTok of a woman reading DMs aloud at a birthday party and my whole body rejected it. I want the truth. And then I want a plan.”

She was my favorite kind of client: motivated, ethical, specific.

“We’ll start with verification,” I said. “Only what you can lawfully give me: shared calendars, family iCloud location history, photos you already possess, public posts, statements you’ve received. Then documentation—build a timeline anyone could follow. Then disclosure in the venue that serves your outcome.” I paused. “Quiet or strategic?”

Her eyes shone but didn’t spill. “Quiet,” she said. “My boys are old enough to Google.”

“Good,” I said. “Mine too.”

Lydia handed me the tote bag like a relay baton. Inside: a printout of the family’s shared calendar (color-coded for “Call,” “Clinic,” “Gala”), screenshots of Venmo descriptions that tried very hard to be clever (🍷 “board” meeting), a handful of crumpled receipts, and a glossy event program from the Hart Foundation gala in September—Paige’s thank-you letter on the back in italic script.

We signed the engagement letter and the consent forms. I pulled a legal pad toward me.

“Where do you feel it in your body when you think he’s lying?” I asked.

She blinked, surprised and relieved, like someone had adjusted the thermostat in an uncomfortable room. “Right here,” she said, pressing the base of her throat. “Like a hand.”

“Good,” I said. “When that feeling flares, write down the time. It’s usually right.”

She laughed without humor. “You’re good at this.”

“I’ve had practice,” I said.

Verification is ninety percent patience, ten percent pattern. Lydia AirDropped me the albums from her phone labeled Special and Holidays. I scrubbed the metadata. Photos taken at “donor dinners” were geotagged, because young waiters love to tag a chef and doctors love to repost. The photos always found their way to Paige’s foundation account first, then to the practice page, then, after a lag, to Noah’s personal Facebook with bland captions about “grateful to serve our community.”

I cross-referenced those timestamps with the family calendar and with the “on call” schedule the practice posted for patients. HIPAA doesn’t cover a rotating schedule taped to a clinic door. Three times in two months, Noah posted photos from tablescapes under strings of lights while his name glowed in red marker on the clinic schedule across town. The schedule does change, yes. It does not change three times without a notation. The notation we did have: an Uber receipt to Paxton House, a boutique hotel with wallpaper the color of money.

Paige’s social feed was a study in curated virtue: kids with donated sneakers, a ribbon-cutting shot flanked by suit jackets, a boomerang of champagne flutes clinking. She rarely posted herself. But her friends did. One selfie at a rooftop bar captured a reflection in a window like a careless ghost—Noah’s profile, sharp and unmistakable if you’ve stared at a face for eleven years.

The Venmo descriptions were the beginners’ version of misdirection: “Board meeting 🍝”, “Strategy sesh 🍾”, “Foundation fuel ☕”. I wasn’t building a criminal case. I was building an argument. If you can make the truth obvious enough, people stop pretending not to see it.

Lydia texted when her throat knotted: 11:24 p.m., said he’s still scrubbing in. At 11:27, a tagged photo on a friend-of-a-friend’s story showed Paige and Noah on the mezzanine of the Halcyon Hotel, frames hung with eucalyptus, a jazz trio in the corner. Lydia and I watched the dots connect in real time, and I could feel her body do that horrible thing—believe and break at the same time.

Two weeks in, the timeline had a shape. Not every Thursday. Every other. Not every gala. Most. Never on Saturdays until soccer season ended. Always under the cover of “donor stewardship,” because philanthropy is the best camouflage for appetite.

We scheduled a check-in. Lydia arrived with a notebook and a steadier grip on her tote bag.

“Tell me the truth in a sentence,” I said, instead of hello.

“My husband is sleeping with his best friend,” she said. “And they’re using the foundation as cover.”

“Good,” I said, because naming is an exorcism. “Now we pick the room.”

With Thanksgiving, I had made a deliberate choice: public, high voltage, cameras rolling. It was the correct move for Sterling and Reagan because their currency was perception, and because they’d already recruited my family into their lie. Lydia’s currency was different: her boys, her home, a silent arrangement with a hospital that is by design allergic to scandal. The room we picked could not be DIY.

We chose Therapeutic Exposure with a corporate twist: the practice’s compliance officer and general counsel present, Lydia’s attorney, and, because women with power deserve to be given tools, the board chair of the Hart Foundation, who also happened to be a retired judge. The only way to make men who love their reflections tell the truth is to hold up a mirror they fear.

We spent a week building the binder. Outside, navy linen. Inside, no adjectives. Tabs:

Timeline: Dates, times, locations, sources. No commentary.

Policy: The practice’s code of conduct; the foundation’s conflict-of-interest statement; donors’ expectations about stewardship.

Documentation: Printouts of public posts; receipts; calendar snippets; the schedule photos; geo-tag maps with pins like braille.

Impact: The boys’ schedules, nights missed, a short statement—three paragraphs—by Lydia about the effect on the family. No tears on the paper. Tears are for bathrooms and cars and kitchens at 2 a.m. Not binders.

Requests: Clear, lawful, proportionate: temporary separation agreement; compliance review; board review of the foundation’s leadership; a commitment to a private, structured disclosure to the boys with a therapist.

I taught Lydia how to ask for what she needed without apologizing for wanting it. We rehearsed answers to the most common dodge-and-weave maneuvers—“You’re misinterpreting,” “It’s complicated,” “You’ve always been jealous of my work.” The rule: answer the question you wish they’d asked? No. Answer the actual question. Then stop talking.

The meeting was set for 8:00 a.m. on a Monday in a conference room that smelled like coffee and toner. The compliance officer sat at one end, the general counsel at the other. The board chair, hair shellacked into mercy and menace, took the middle. Lydia’s lawyer sat beside her. I took the seat behind them, the way I do: present, silent, undeniable.

Noah arrived five minutes late with the look men wear when they plan to charm their way back into the room. Paige followed in a blazer you can’t afford on a nonprofit salary. She clutched a notebook and a pen like both would transform into weapons if she just believed hard enough.

Lydia did not look at either of them. She addressed the table.

“Thank you for meeting,” she said. “I’ve brought documentation. I’m going to give you the headlines and then you can ask questions.”

General counsel nodded. A note-taker somewhere in the room clicked a key. The world slid into record.

“Over the past six months,” Lydia said, voice steady, “my husband and the foundation director have used donor events and on-call schedules to facilitate an affair. I have a timeline, receipts, and public posts. I am not here to embarrass anyone. I am here to insist on compliance with your own rules and to establish a safe transition for my children.”

She handed the binder to the compliance officer, who began to turn pages with the reverence auditors reserve for perfect math. The board chair took her copy and made a mark only once—for Section 3.1 of the conflict-of-interest policy.

Noah cleared his throat. “This is a misunderstanding,” he began. “My wife—”

Lydia lifted a palm. “The documents are in front of you,” she said to the table, without turning. “Please review them.”

Paige tried smile-and-minimize. “Lydia, we’re like family. This is—”

The board chair’s pen tapped the table once, sharp. “Ms. Sutter,” she said (Paige’s last name, delivered like an indictment), “be silent unless asked a question.”

I almost liked that woman.

General counsel lifted his eyes. “For the record, Mr. Hart,” he said, “is there any explanation for these receipts under company policy?”

Noah glanced at Paige, then at the paper. He chose his lie and tried to stretch it over the mountain. “Donor cultivation.”

“Donor cultivation,” the compliance officer repeated, bland as oatmeal. “At the Halcyon Hotel, after hours, while on the call schedule?”

Silence. Not a punishable offense in a courtroom; an admission in a marriage.

The board chair closed the binder. “Here’s what will happen,” she said. “Effective immediately, Ms. Sutter is placed on administrative leave pending a board review under Section 3.1. Mr. Hart will be removed from the foundation’s public-facing events until the practice completes its own review under Section 4 of the code. Counsel will draft a temporary separation agreement for the Harts with provisions ensuring custody stability. The foundation will retain an outside firm to audit event expenses for the past twelve months.”

Paige made a tiny noise, a little squeak of a balloon pricked by policy. Noah opened his mouth and closed it again.

“Additionally,” the board chair continued, “we will schedule a guided disclosure with a therapist for the Hart children. Mr. Hart will be present. Ms. Sutter will not. We will protect donors from scandal. We will protect patients from disruption. We will not protect liars from consequences.”

Lydia did not cry. She folded her hands and said, “Thank you.” It was the politest detonation I have ever seen.

Outside the glass doors, in the hallway where interns pretend to make calls so they can listen, Lydia finally allowed herself to breathe the kind of breath you only take inside your own chest. She leaned against the wall and closed her eyes.

“Was that enough?” she asked me.

“It was exactly enough,” I said.

Life did what life does: rearranged itself around the facts.

The foundation board announced “leadership changes” with the same sentence structure Whitfield Luxury had used for Garrett. Paige “resigned to pursue other opportunities.” She scrubbed her Instagram of donors and replaced them with sunsets. The practice installed a compliance training that bored everyone on purpose. Noah moved into a rental with beige carpet, saw the boys on a schedule written by a therapist who might as well have been Moses bringing law down the mountain, and learned to pack lunches.

Lydia kept the house, kept her job at the interior design studio in Dilworth, kept her mornings with coffee and the quiet hum of a refrigerator that, like mine, has seen enough. She took down the wedding photo and replaced it with a framed painting the boys made in kindergarten—handprints in blue and green and a crooked heart in the middle. She sent me a text the day the board chair finalized the audit: No more donor dinners. She’ll never run that room again. I sent back a thumbs-up. Then: You did that.

Two months later, she came to my office with a pie because people still bring pies to women who help them stay upright. We sat with forks and paper plates and the slack-jawed pleasure of sugar, and she told me the latest:

“The boys are okay,” she said. “They’re angry in the way that makes me proud of them. Noah is… practicing not being the center of a room. Paige moved to Raleigh. I don’t Google her anymore.”

“You’re doing well,” I said.

“I know,” she said. “That’s the strangest part. I miss the idea of what we were more than I miss who he was.”

“That’s not strange,” I said. “That’s grief.”

She nodded. “You did it loud,” she said. “I did it quiet. I think both were right.”

“Both were necessary,” I said.

When she left, she hugged me the way people do when the body remembers gratitude even if the mind is too tired to narrate it. After she was gone, I stood at the window of my office and looked out at the parking lot. A man was teaching his kid to ride a bike between the lines. He ran beside the wobbling handlebars, eyes on the goal line that existed only in his head, then let go. The kid went three feet on her own and crashed into a minivan, then got up grinning. Practice, fail, repeat. That’s life. That’s how we all learn balance.

Not everything in my world cooperated with my new preference for quiet. Reagan’s name crossed my inbox again when a conference organizer forwarded a “wellness speaker” pitch she’d received, attached to an email that read, Given recent events, we wanted your take. Her topic: Radical Honesty: Building Trust in a Filtered World. I laughed so hard I had to put my head on the desk. Then I sent the organizer a one-line reply: Choose speakers whose lives won’t make your audience feel like accomplices.

Sterling filed his taxes late, because some habits only break under pressure and April isn’t a therapist. He tried a small pivot during a pickup exchange and told me he’d signed up for a co-parenting class. I told him good. He texted later that he’d passed the first module and it “taught him active listening.” I resisted the urge to send a certificate from Canva.

On a Saturday morning in May, Carol knocked with a paper bag of strawberry muffins and the slightly panicked cheer of a woman who cannot stand silence between people she loves. She cried again, but in the gentler way, like a summer rain that knows its job is just to cool the air.

“I forgave her,” she said, looking at her hands. “I do not excuse her. There’s a difference, isn’t there?”

“There is,” I said.

“She wanted me to ask you to coffee,” Carol added, bracing for impact. “I told her the consequences of her choices were not subject to my calendar.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it.

When she left, she put her palm against the doorframe for a second, like she was blessing the house, and something inside me softened in a place I hadn’t checked in months. Not for Reagan. For mothers trying to love adult children who have burned maps you drew for them with your own life.

That night, after the girls fell asleep in a tangle of cousins at my sister’s house, I sat alone on the balcony with a blanket and the lake and a glass of something honest. My inbox dinged: a new client. Subject line: I need the quiet one. I clicked it open and saw a familiar pattern—late nights, a best friend, a nonprofit that thinks cause work baptizes appetite. I wrote back the sentence that has become my business and my life: We can get you your reality back. Then we’ll decide how to show it to the world.

The truth doesn’t need a marketing campaign. It needs a room, the right people in chairs, a binder, a voice that doesn’t shake. Sometimes it needs a projector and three cameras. Sometimes it needs a retired judge with a pen. Either way, it needs timing.

My phone buzzed again. A text from Lydia: a photo of her boys on bikes, helmets crooked, everything a little messy and alive. We’re okay, she wrote.

I put the phone down and watched the lake crease under the evening breeze. Somewhere behind me, the fridge hummed—steady, faithful, indifferent to drama. I breathed in, out. The air had that early-summer softness that makes you believe bad seasons end. Not with fireworks, but with a light you can read by.

I went to bed. I slept. And in the morning, I woke with a list in my head and a life that had finally learned to live without secrets.

Part Four

In May, I wrote a code of ethics.

Not the kind you print and forget. A real one. Two pages. Plain language. No Latin. It fit on my website between Services and Contact, and it said, among other things: We only work to restore reality for the person being lied to. We don’t break laws. We don’t endanger kids. We don’t manufacture scenes for entertainment. When I hit publish, it felt like a small treaty with who I wanted to be in the second half of my life: the woman who picks her lines and keeps them.

The emails that followed proved I’d need it.

A venture fund out of Raleigh offered me a check with too many commas to “verify a rumor” about a competitor’s spouse before a merger vote. A bachelor wanted me to live-stream his “gotcha” at a rehearsal dinner. An influencer pitched a collab where I’d read “cheater DMs” over music on TikTok. I said no to all of it. The money tried to flirt. My no learned to be attractive on its own.

The case that tested me arrived with a subject line that made my skin crawl: I want him to hurt. The sender was a woman my age with three kids and a pain so loud it crackled across the screen. Her husband had done everything Sterling did and then some. She wanted a Thanksgiving. With cameras. With their children in the front row.

“I can give you proof,” I said on the phone. “I can give you strategy. I cannot give you an audience of minors.”

“It would be poetic,” she said, desperate. “They need to see who he is.”

“No,” I said, and explained my rule: We don’t turn children into props for adult clarity. She cried—the exhausted kind of cry that comes when someone takes away the stage you wanted to burn down—and then she thanked me. Later, we built a disclosure with her therapist and his HR rep in the room. It landed. Quietly. Correctly. She sent me a single sunflower emoji afterward, which was better than any review.

Boundaries are best tested by the people who taught you not to have them. Which is why, of course, Reagan tried again.

First it was the flyer. A conference organizer forwarded it with a single question mark. RADICAL HONESTY: Building Trust in a Filtered World, featuring… Reagan. I laughed in my car until I had to pull into a Harris Teeter lot. I wrote the organizer a kind email suggesting alternative speakers who wouldn’t make the audience feel complicit in their own manipulation.

Next it was the post. She wrote a long “mental health” essay on Facebook—vague enough to sue no one, pointed enough to let her friends infer it was me. “Some people weaponize ‘truth’ to build their brand,” she typed. “Forgiveness is a journey.” The comments section clucked and cooed. I did the thing most people don’t and it felt like sainthood: nothing. I did nothing. Silence is a tool if you can stand the itch.

Then she did the one thing my code doesn’t negotiate with: she messaged Madison.

Aunt Reagan misses you. Can we get ice cream? Don’t tell Mom—it’ll be our secret 🫶.

My daughter is seven, but she is my daughter. She handed me the iPad like it held a live wire.

“What do we do?” she asked.

“We follow our rules,” I said. I hugged her, then sat down at my desk, opened a new document titled Cease and Desist, and called Escobar.

“Emergency motion,” Escobar said after I read the message aloud. “No-contact regarding minors. We’ll walk that into chambers this afternoon.”

We did. The judge—a woman who looked like she’d had lunch without checking her phone—read the message, glanced over her glasses, and signed. By dinner, Reagan’s inbox held a very different kind of letter. Carol called me from her car, voice shaking. “I didn’t know,” she said. “I told her… I told her she has to stop reaching for you through your children.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it. That night I sat on the floor of Madison’s room while she pretended to sleep and explained boundaries like they were magic. Secrets are not love. Adults who ask you to hide things are not safe in that moment. You can tell me anything. You will never be in trouble for telling me the truth.

She listened, wide-eyed, and then asked if she could still tell me her “surprise” drawings in secret. I told her yes. Some secrecy is art.

Sterling, to his credit, handled the message correctly. He texted: I spoke to Reagan. That was wrong. It won’t happen again. He copied Carol. Then he wrote, unprompted: If you want, we can tell the girls together that they should never hide contact from either of us. We did. Co-parenting is a muscle you can learn to use without tearing other tissue.

His next test arrived in June. He was scheduled for a weekend with the girls when his father had a cardiac scare—one of those middle-of-the-night calls that turn grown men tempers into boys again. He texted at 2 a.m.: Dad’s at Presbyterian. I don’t want to cancel. Can we swap days? Old Sterling would’ve assumed. New Sterling asked. I said yes and offered to bring the girls to the hospital cafeteria so they could hug their grandfather. He said thank you three times—once in text, once on the phone, once in the hallway outside the elevator where we met and exchanged small creatures and a bag of snacks like diplomats.

Robert lived. Because of course the universe has a sense of humor about men who nearly die and then tell everybody about it for twenty years. The girls drew him a card with a heart wearing a stethoscope. He cried and said something about Navy grit and God, which are the same thing to him.

In July, a corporate client tried again to get me to “bend.” An athletic-wear company slid into my inbox with a “family values initiative” based on exposing cheaters in the influencer community. “We’d love to sponsor your work,” the email purred, “and build a content pipeline.” Content pipeline. Like betrayal is oil you pump and refine.

I wrote back: I’m not your PR arm. I do not do content. I restore people’s reality and help them make plans. That’s it.

They offered mid-six figures. I reread my code. Then I turned down a check that could have paid for college. I took a walk. I reminded myself that money buys you relief and sometimes a couch you can nap on without shame. It doesn’t buy back self-respect once you sell it wholesale.

Work grew anyway. Word-of-mouth is a river you don’t need to advertise if you know where the headwaters are. Lydia sent people; the Cornelius client sent more; a therapist spoke my name into a room full of women whose mothers would’ve stayed and whose daughters might not have to. I hired an associate—Jules, twenty-seven, former newsroom researcher with a spine like a bridge and ethics sharper than mine at her age. I taught her my rules. She taught me to use a spreadsheet filter I didn’t know existed. We built a wall calendar no one else could understand and began to say no to at least one case a week.

In August, I took the girls to the beach. We ate shrimp on paper plates and fed fries to gulls against our better judgment. On the third night, after the sun dragged itself into the ocean like a tired coin, Madison asked if we could do “the video thing.”

“What video thing?” I asked.

“The family gratitude video,” she said. “Not the… you know.”

“We can,” I said, “but only if you help me make it.”

We did. In the rental, at the wobbly kitchen table, we built a deck called Small Things. Slide one: Madison’s piano recital with the wrong note nobody noticed but her. Slide two: McKenzie’s first goal with a shin guard on the wrong leg. Slide three: Pop’s hospital wristband cut in half and thrown away. Slide four: Lake Norman at 7 a.m., the light that makes you believe in clean slates. We didn’t include Sterling or Reagan or anyone who makes flatware clink loudly in your memory. We included the mac-and-cheese recipes side-by-side and labeled them Both/And.

We pressed play on my laptop in our living room when we got home, just us. No guests. No cameras. No exhibits. We cried twice (me), laughed six times (them), and gave it a thumbs-up rating like it was a movie on a plane. That night I realized something that would have sounded like a fortune cookie a year earlier: the first presentation was a scalpel. This one was a suture.

Autumn returned the way it always does, like a rumor we’re okay believing because it’s been right so many times. The lake turned cold on the surface and warm under it, a physics lesson I didn’t remember from school but trusted because my body could feel it. The business did its work. The girls learned to pack their school bags the night before. Sterling learned to text on my way instead of sending a voice memo that sounded like a podcast. Reagan… well, Reagan found a stage, as people like Reagan always do.

In September she announced a podcast—of course she did—called Unfiltered: My Journey Back to Me. The trailer made its way to me through three sources, as if the city wanted to see whether I had the discipline not to take the bait. I listened once. She told a story in which she was both victim and hero and I was a lesson she’d learned “about boundaries and betrayal on both sides.” I turned it off at the first ad break. Carol sent a text two days later: I told her I wouldn’t listen if she talked about you or the girls. I meant it. That helped in a place most things don’t reach.

October brought a last test I didn’t expect. Sterling asked to meet for coffee, which is usually code for a request he should send in email. I picked a café I liked two neighborhoods from any history. He arrived on time, hands empty, which I took as a good sign. We sat outside under the kind of umbrella that makes sun feel curated.

“I messed up,” he said, and didn’t try to soften it with context. “I’ve been seeing someone. A woman at the lot. It’s been three months. I want to tell the girls before they hear it elsewhere.”

“Our agreement,” I said, and he nodded before I finished.

“Six months,” he recited. “Therapist approval. No sleepovers with the girls there.”

“And you don’t tell them she’s the reason we’re not together,” I added, not because I thought he would but because agreements help men remember.

He nodded again. “I’ll wait,” he said. “I just… wanted to say it out loud to the one person who will hold me to it.”

He said it with no hope of impressing me. That was new.

“You can do right things for the right reasons now,” I said.

“I am trying,” he said.

“Good,” I said. “Keep trying.”

A week later he texted: I broke it off. Six months is six months. Turns out being an adult is… being an adult. Progress often looks like someone restating the obvious and finally believing it.

The year marked itself in small firsts. The girls carved pumpkins that didn’t look like crime scenes. I learned to sleep with the window open an inch even in November, because cold air makes me feel like my lungs belong to me. Jules and I built a template for Guided Disclosures that other firms asked to buy; we sent it for free to two legal aid clinics instead. Lydia sent a photo of her boys handing out turkeys with the foundation’s new director, a woman with a résumé, not a curated feed.

And then, because time is a circle and the calendar is a mischievous friend, Thanksgiving came back.

“Here?” my mother asked, careful, the way you ask a recovering person if she wants to go back to the room where she once fell.

“Here,” I said. I invited my parents. I invited my sister. I did not invite Sterling’s parents; they went to Asheville to “do a cabin.” I invited Sterling for pie after dinner, without champagne. I invited Carol, and she wrote back a short, kind no—her first boundary I have ever loved.

I cooked. Not like I was auditioning for forgiveness—just enough to make the house smell like a childhood I wanted to keep. The girls set the table with cloth napkins because they like the way the rings feel in their small hands. My father told his Navy story; my mother made the green bean casserole we’ve all made fun of and finished every year. We ate. We put away plates. We sat in the living room, and when the timing felt right, Madison asked, “Can we do the video?”

“Of course,” I said, and opened Small Things again. We watched the year run past our faces. The girls leaned into my shoulders on either side like commas in a sentence that never needs an ending. When the last slide faded, the room stayed quiet for the kind of silence people pay for on retreats.

“I’m grateful,” McKenzie announced, “for two houses with mac and cheese.”

“I’m grateful,” Madison said, “for truth. Even when it’s spicy.”

My mother raised her glass. “To spicy truth,” she said, like the Southern lady she is who always wanted an excuse to toast honesty.

Sterling arrived at seven with a grocery-store pie and flowers. He hugged my parents. He told the girls their hair looked like they belonged to a rock band. He thanked me for inviting him and didn’t stay past eight. On his way out, he paused by the mantle, the place where, a year earlier, I’d stood holding a remote like a gavel.

“That night,” he said, soft. “You gave me a lesson I deserved. I hated you for it. I don’t now.”

“It wasn’t for you,” I said. “It was for me. And for them.”

“I know,” he said. He hesitated, then added, “Thank you for not letting me turn you into the villain in my story.”

“Tell better stories,” I said.

“I’m trying,” he repeated, and left without looking back.

After everyone went home and the girls fell asleep in a tangle of new pajamas and old blankets, I stood in the doorway and thought about the strange grace of being the adult in the room when you were raised to be the good girl in the corner. I thought about the women in my inbox who still begin with I think I’m crazy. I thought about Reagan and the way some people mistake a microphone for absolution. I thought about Lydia’s boys on their bikes and the way falling is how you learn to steer.

I went downstairs, put the last dish in the rack, and turned off the kitchen light. The fridge hummed. Detective jumped onto the counter with the practiced stealth of a cat who believes your rules are aspirational. I lifted him to the floor and laughed in a whisper so I wouldn’t wake the house.

Out on the balcony, Lake Norman held the moon in place like a prayer you can say even if you don’t believe in the person it’s addressed to. I wrapped a blanket around my shoulders and let the air touch my face.

When I found out my best friend was helping my husband cheat, I thought revenge would feel like a standing ovation. It didn’t. It felt like putting down a heavy thing I’d been carrying for other people, then picking up only what belonged to me. The lesson I gave them wasn’t a script to read or a slogan to sell. It was simple and unglamorous: Truth doesn’t negotiate. Consequences aren’t cruelty. Boundaries are love in grown-up clothes.

They learned it. Slowly. Loudly. Quietly. In their different cities and their different rooms.

And I kept the rest: the peace, the house that smells like cinnamon twice a year, the daughters who say “spicy truth” and then ask for more pie, the inbox that starts with please help and ends with we’re okay.

The truth never needed my marketing. It needed my timing. It needed me to stop apologizing for it. It needed a remote, a binder, a room, and a woman who had run out of patience for beautiful lies.

I went to bed. I slept. And in the morning, I woke up to a life that didn’t look like a campaign anymore. It looked like mine.

News

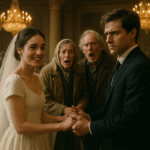

He Said He Had No Family… Until an Elderly Couple Interrupted Our Wedding CH2

For illustrative purposes only I believed him. Javier always claimed he was an orphan. He spoke little about his childhood,…

I Donated the Mansion to Charity—My Mother-in-Law’s Screams Echoed Through the House… CH2

Newly divorced, I donated the mansion to charity; my mother-in-law shouted, “So my 12 relatives are going to be homeless?”…

My Husband Said, “Don’t lecture My Kids. Get Your Own.” When I Tried To Correct My Stepson, I Just… CH2

Part One — How a Family Begins The first time a school nurse called my name, it was for a…

MY 6-YEAR-OLD NIECE WENT TO THE BEACH WITH MY WIFE AND MOTHER-IN-LAW. WHEN THEY RETURNED WITHOUT HER, I ASKED, “WHERE IS NIECE?” CH2

Part One — The Sound a House Makes The front door opened and slammed behind them the way it does…

“Forgive me, Galya, but after my passing you’ll have to move out,” Anatoly said calmly to his wife. “I’ve bequeathed the apartment to my son… CH2

“Sorry, Galya, but after my death you’ll have to vacate this apartment,” Anatoly told his wife. “I’m leaving it to…

My Husband Found Out I Accidentally Gave Him an Infection—Now I’m Divorced, Jobless, and Alone… CH2

Part One The phone call came on a Tuesday, the kind of midweek no one remembers until it cuts the…

End of content

No more pages to load