Part I

I learned pretty early that some houses keep two sets of books. There’s the ledger your parents show the world—report cards magneted to the fridge, framed photos from the town Christmas parade, the way your dad says “we” when he means “Larry mowed the lawn before breakfast.” And then there’s the other accounting, the one where praise and help and second chances get distributed by a system nobody writes down.

In our house, Jordan’s column was always in the black. Mine balanced only when I made it.

When I left for State University at eighteen, nobody cried at the driveway. Dad hugged me the way men hug at the end of softball games, two claps on the back and a “go get ’em,” then asked if I remembered to lock the shed. Mom tucked a twenty into my palm and told me to call weekly. Jordan—then a high school junior with a mop of hair and an allergy to alarms—took my desk after I carried it downstairs, sat at it for sixty seconds, and said he liked the view.

Two of my friends brought me to campus in an old Civic that coughed under its own enthusiasm. We unloaded in one run. They helped me hang posters and stack cinderblocks under the dorm bed and then insisted on buying dinner, their idea of a proper sendoff. The dining hall smelled like bleach and marinara. They asked where my parents were and I deployed the line that would become reflex: “We’re pretty independent,” I said. “Always have been.” It came out practiced. It was.

My week one budget had two columns: “must” and “would be nice.” The first was books and bus fare and cafeteria meal swipes. The second read like a fortune cookie for kids with allowances: new sneakers, coffee that wasn’t poured out of a drum, a day you didn’t spend counting quarters. Ramen went in a drawer under my bed. Peanut butter went everywhere. My first campus job, at the dining hall, was mopping and dishing and learning how much food people leave when they aren’t paying attention to money.

At Thanksgiving, I arrived home to find my parents not just paying attention but celebrating it. A new 60-inch television glowed in the living room like a southern sun, speakers crouched on either side like obedient dogs.

“What do you think?” Mom asked, eyes bright. “Your father got a little bonus. Our old set was on its last legs.”

It had been fine in August.

“It’s…big,” I said.

“You deserve nice things sometimes,” she added, ruffling Jordan’s hair as he jogged in from the kitchen with a fistful of chips. I thought about the cost of my used Biology 211 textbook and how many dining hall hours it took to pester the librarian into letting me renew the reserve copy yet again. That night I lay in my childhood room staring at little constellations I’d drawn in pencil on the ceiling when I was twelve and did the math on napkins. I would need ten more hours a week next semester—fifteen would be better.

I said nothing. That was the rule I’d learned: the doers do, the talkers talk, the parents look pleased with both.

By sophomore year, I’d learned that one good thing leads to two jobs. The coffee shop manager liked how fast I counted change in my head and added me to opening shifts; a local clothing store hired me for weekends after seeing “never late” on the reference form; when the campus catering office needed someone to carry trays and smile at donors at alumni galas, they called me because I owned black shoes and could figure out any room’s choreography.

My phone calls home on Sundays played like highlights. I told them about classes I loved in short paragraphs and work in shorter ones. Mom told me who from church had gotten engaged and that my cousin’s baby had a lot of hair. Dad updated me on yard work and then held the phone near Jordan so he could yell “State!” when the football game turned good.

They asked about my grades—always “fantastic!”—and if I was “making friends.” No one asked if I had enough money for books that semester. No one had to; the house had already decided that was my column.

When Jordan graduated high school three years later, 2.7 and a handshake, Dad gave a speech that had more pride in it than any I’d heard for a man who wasn’t retiring. At dinner after, Mom announced that they’d be paying Jordan’s full tuition at State. “We want you to focus on being a student,” she told him, squeezing his shoulder. “No distractions like your brother had.”

I drank water the wrong way and nobody noticed.

Two weeks later, they surprised him with a brand-new Mustang. The bow on the hood matched his tie.

I drove back to campus in my ’04 Honda with a passenger window that wouldn’t go down unless you were willing to commit to never getting it up again. The AC wheezed. The odometer read 149,748, and if I’d believed in signs I would have looked for one there. Instead I set another early alarm.

There’s a particular kind of freedom to being broke and stubborn. The campus looked like a movie set in April: students lying spread-eagle on the quad, Frisbees making only the expected arcs, someone strumming a guitar under a tree like the admissions brochure had cast them. I waved and went to my internship, a small marketing shop where the owner—Sharon, who wore sneakers with her suits—liked that I showed up early and asked questions like “What does this do for the client?” instead of “Will there be pizza?”

She paid me enough to shift my budget from triage to treatment. I made my first interest payments a year before graduation because a blog post said it was the smart thing to do. My academic adviser shook her head when she saw the rings under my eyes. “Your grades are excellent,” she said. “But talk to your parents. Most families contribute something. Even on books.”

I smiled the version of my smile that had learned which conversations weren’t worth starting. “That’s not an option, Professor Lambert,” I said. “But thank you.”

On my dad’s fiftieth, the house filled with my mother’s lasagnas. Jordan rolled up in the Mustang with three friends crammed into the backseat like a college brochure gone to seed. Over garlic bread, he announced he’d changed his major a third time. “Business had too much math; psych, too much reading,” he said. “Communications is probably my thing.”

Mom piled cake on his plate and called it “finding your passion.” Later, I heard Dad tell him near the sink, “Take your time. We budgeted five years. Enjoy it. College is the only time you’re allowed to be a little irresponsible.”

I had taken summer credits every year because calculators don’t care about passion. Responsible looks righteous only from the outside; from the inside it looks like folding up your own joy and placing it on a high shelf.

Graduation came the way earnesty always does: with a cap that didn’t fit and a tassel that smelled like a warehouse. My parents came, took a handful of photos, and left early to take Jordan and his friends to dinner because they’d promised. “We’ll celebrate you properly back home,” Mom said, and I said “Of course” because I had trained my whole body to say “of course” even while my stomach learned to tie knots my brain couldn’t untie with words.

The celebration back home was pizza around a TV tuned to a baseball game. Dad clapped me on the shoulder and told me to keep that job at the firm I’d interned with. “Good work is its own reward,” he said, the kind of sentence that feels wholesome until you realize it’s also a budget strategy.

The first lean months came with dignity and a spreadsheet. Rent for a studio that was the cheapest square footage within ten miles of a siren. Student loan autopay set to a number that made me breathe shallow and eat rice. Thrift-store chairs. A bedframe that creaked like a conscience. I learned how long a pair of shoes can be resoled and what kind of pasta stretches without making you feel poor.

Jordan’s life ran parallel and louder: fraternity stories shouted into a phone on Sundays; a fully furnished apartment I’d never see; trips to beaches where men wear linen shirts unbuttoned because they can; calls where my parents laughed indulgently at boy-college things it would’ve gotten me banned to do. “College is about the experience,” Dad said. I tried to conjure one and came up with a study group that met in the one retail store that let us sit in the shoe section when the manager we liked was working.

At twenty-seven, I paid down enough debt to taste it. They call this a snowball, advisers with better lighting than mine said online: you push and push and it barely tips and then one day it starts rolling and you hear it move. I made extra payments when I could, never missed when I couldn’t. When you have a mountain as a roommate, you learn to make friends with climbing.

I became useful at work to the kind of people who didn’t like surprises. “Larry will do it,” managers said, and then apologized with their eyes. The reputation followed me the way certain dogs follow people who smell like treats. “Do you ever relax?” Diane asked one Friday when she caught me slipping a tie out of my desk drawer at 6:45 p.m. “I will relax when I am debt-free,” I said, and meant it more than I meant any vow I’d ever told a person I loved.

Jordan graduated into my thirties. Six years for a bachelor’s, the tassel at an angle that said “good enough.” He moved home because of course he did. The house he landed in had grown a new wing for his needs apparently, one where car payments and phone bills and a monthly envelope slipped across a counter became gestures of love. “He’s just finding himself,” Mom said, pronouncing it like a major. I wondered if I’d missed the elective.

When he disliked his first job, he quit. When he disliked the second, he took eight months off to “reassess.” He went to Costa Rica because mental health and also Instagram. He came back with a tattoo of a wave on his forearm and eyes that looked at the horizon like it owed him something.

Dad helped him find a third job. They co-signed his apartment lease. They paid the security deposit and the first three months’ rent and aired their pride at dinner like a banner that had been waiting in the garage for a parade. “We’re so proud of him,” Dad told me over the phone. I said, “That’s great,” and bit the inside of my lip hard enough to anchor myself.

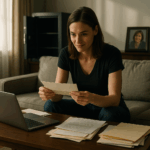

At thirty-four, I made my last payment. The confirmation screen on my laptop seemed humble in the face of that decade. No confetti animation. No fireworks. Just a balance that read $0.00 and a button that said DONE. I stared until the letters blurred and then I laughed the kind of laugh that shakes something loose in your bones.

I splurged on takeout Thai and ate it in my studio with a beer that wasn’t whatever was the cheapest that week. It tasted like reward and also like maintenance because the next question came fast. If you don’t have to carry this anymore, what do you want? Desire hit me like altitude. I realized I didn’t quite recognize the feeling.

Four days later, Sulttera Marketing called. They’d sniffed around before; I’d said vague things about timing. This time, when the recruiter’s voice said “London,” my body went hot then cold. The job title said Senior Director. The salary said breathing room. The relocation package said they’d put me on a plane and hand me keys. The idea said “remember when you wanted to be the kind of person who kept a passport handy just in case life threw you a door?”

I accepted before I could be responsible about it.

I put a one-way ticket in my wallet like an amulet. For a week I touched it absentmindedly the way people touch their throats to make sure a chain is still there. I told nobody because I wanted the decision to feel like mine for longer than a news cycle. And then Mom called to say we were all doing dinner at Salvatore’s on Saturday. “We thought it would be nice,” she said. Her voice had that extra brightness it gets when she’s smuggling an agenda. “A family thing. You remember the private room in back. Dress nicely.”

Maybe they were celebrating Dad’s work anniversary. Maybe Mom had won the garden club’s prized azalea. Maybe they wanted to talk about the Europe trip Jordan was posting about. The invitation smelled like something I’d learned to recognize—this will go how we want if you’re polite enough. Still, they were my parents. They were my brother. It was a family thing.

I decided to tell them in person about London. Not as a confession. As a courtesy. As strategy too, I guess. Better to drop your bomb when everyone’s already holding a knife and fork.

I arrived ten minutes early because the idea of being late to things in the last week of a life made my skin itch. The hostess led me to the private room where the lights were the color rich people request when they want their food to look photogenic. Mom stood to hug me and pressed her cheek to mine for a second longer than necessary. Dad shook my hand like we were meeting after a small victory. “Good to see you, son,” he said.

We talked about work and weather and my apartment flooding once when the upstairs neighbor’s fish tank tipped. Mom told me a story about a raccoon in her garden. Dad bragged about a walleye he had pulled out of the river on a Tuesday like he had been waiting at the bank and the fish had been on the schedule.

Jordan and Amanda arrived a half hour late, charged with the kind of apology that isn’t one. He had grown into the kind of man who looked always like he had just come from good lighting. Amanda introduced a perfume that smelled expensive, the kind of scent that might be called Heritage. They ordered a bottle of wine without asking. I asked for water with lemon. “Come on, live a little,” Jordan said. “Mom and Dad are paying.” I smiled a fraction. Old habits.

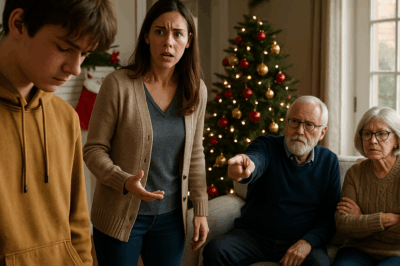

We told childhood stories like we were auditioning for a reunion. Dad checked his watch like a judge clearing his throat. Then he cleared his throat. “We asked you here for a reason,” he said. The sentence landed like something heavy on a banquet table, cutlery ricocheting—the room returned to being a room.

Mom opened a manila envelope. “Tyler is gifted,” she announced the way people present a certificate. “His teacher says he’s ahead. There’s a school—Westfield Academy. They have this program that goes from pre-K through high school. It’s…comprehensive.” She let the word sit. “It would guarantee him so much.”

“Seventy thousand,” Dad added in a tone he thinks sounds practical and to other people sounds like push.

They slid papers toward me.

“Jordan and Amanda will make payments,” Mom soothed. “We’ll put down the deposit. It’s just the rate; the school requires a stable co-signer. Larry, with your excellent credit…” She reached out and patted my knuckles like this was dessert.

I looked at the number. It was comical the way certain numbers are when they break into your life already wearing a costume. I thought of bicycles with training wheels. I thought of my spreadsheet and the way the last cell had turned green. I thought about the weight of a boarding pass.

Jordan was already nodding. “We’d never miss a payment,” he said in a tone that suggested payments happened to other people like weather.

I dipped the papers back toward the center of the table with two fingers, like I was returning a fish to a lake.

“Have you considered public school?” I asked.

They stared at me, temporarily confused by a category error. Jordan recovered first. “Be serious,” he said. “For Tyler?”

“Public school produced me,” I said. “I worked hard, but it’s…not disqualifying.”

Mom called me disrespectful without using the word. Dad invoked family. Jordan used the phrase “your blood.” Amanda’s eyes flickered the way intelligent people’s eyes do when the facts in front of them don’t align with the narrative they’ve been fed and they realize they may have been chewing a story without noticing the gristle.

There is a part of me that wanted to blow up then. Swear in ways my mother couldn’t excuse, point at the television that had replaced a book budget, shout down the litany: Mustang, tuition, rent, a sabbatical to “reassess.” Instead, I let my voice do what it has taught my body to do: balance.

“Co-signing is a serious legal commitment,” I said. “If you default, I am responsible. Given the pattern here, I don’t consider that hypothetical.”

Dad made a noise like a car failing an emissions test. Jordan called me a martyr. Mom told me I was making this about old things. I put my hand on my wallet and felt the paper there, the way people press their skin to the throats of sleeping babies to make sure they’re still breathing.

“We will revisit this,” Mom announced, the way you end a meeting when you’ve lost it.

“No,” I said. “We won’t. I will not co-sign a loan. Not for seventy thousand. Not for seventy.”

Jordan slammed his napkin. The waiter flinched at the door. Amanda looked at the window like her exit ought to be there.

“There’s something else,” I said, before Dad could deliver the next line about respect and restaurants. I took the ticket from my wallet and set it on the linen between the waiter’s folded corners.

I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t apologize for its imprint. “I’m moving to London,” I said. “The Sulttera offer. I leave in three weeks.”

Three faces performed shock, each one a different play. The fourth—the newest, the most interesting—looked from the paper to my eyes and back and then, despite herself, smiled. Small. Like a person seeing a path through the woods for the first time.

Part II

For a second after the word “London,” the room made the sound a theater makes when the fire alarm fails to go off—everyone holds their breath like that will put the smoke back in the wall.

Dad was first. He blinked twice and then did the math out loud as if that would change the sum. “London as in…England.”

“Yes,” I said. “The one with the river and the big clock.”

Mom’s hand found the papers again, like touching a different kind of page would make mine disappear. Jordan snorted in a way that once charmed guidance counselors. “You’re moving to another country now? That’s convenient. Just when your nephew needs you.”

“Tyler needs parents who can pay their own bills,” I said, not unkindly. “He also needs to see the adults in his life say ‘no’ to bad math.”

Amanda’s eyes flicked to me, then to the envelope, then to Jordan, and back, like she’d forgotten whose script she was in. If she’d had a pen, she would have underlined.

Mom spoke like a nurse smoothing a blanket. “We asked you here because we trust you,” she said. “Because you’re steady. Because you always have been. It’s what families do. They lean on the strongest beam.”

“Beams crack under bad houses,” I said. “And cosigning a seventy-thousand-dollar note on a preschool is not reinforcement; it’s negligence.”

Dad’s jaw set in the shape of an old rule. “Don’t talk to your mother like that.”

“I’m talking to the idea,” I said. “The one where my independence is a resource to be spent forever, while Jordan’s dependence is a virtue to be rewarded.”

Jordan’s hand hit the linen hard enough to rattle silverware. “You act like being generous is a crime. Not everyone wants to be a martyr about everything, Larry.”

“Martyrs die,” I said. “I just paid off a loan.”

A waiter hovered and then retreated, trailing the smell of butter. I watched Mom watch him go and wondered what she would have tipped if she’d had the check. Jordan leaned forward, conspiratorial. “It’s just a signature,” he said. “You wouldn’t have to pay anything.”

“Right,” I said. “And those are just words. Legally binding words. Words that attach to credit reports and interest rates and my ability to do anything else with my life. Words that follow me for fifteen years if you decide Costa Rica needs your attention again.”

His face flushed the particular red that comes with being seen. “That was for my mental health.”

“Then maybe prioritize your mental health over luxury schools,” I said. “Or pick a magnet program. Or buy fewer camera lenses.”

“Enough,” Dad said, which in our house has always meant “the conversation is over because I dislike it.” He shifted to the tone he uses with neighbors whose dog is a problem. “We are your family. Family asks for help. Family helps.”

“Equally?” I asked.

Silence sat down with us at the table.

“You learned a work ethic,” Dad said finally, as if he were offering me a trophy. “We didn’t want to rob you of that. And Jordan—well, he needed more. We adjusted as parents.”

I thought of me at nineteen, bleary-eyed at the coffee shop at 5:30 a.m., pouring drip for a professor who tipped in coins, and I thought of Jordan at nineteen, leaning back in a chair at a fraternity house, telling a story with a borrowed watch flashing under the light. “You adjusted,” I said. “And then you never readjusted.”

Mom’s voice came thin and tired and still somehow carrying all the authority she wanted. “You’re dredging up ancient history.”

“No,” I said, calm as arithmetic. “I’m pointing out a line. The one that runs from a ‘practically ancient’ TV to a Mustang to six years of tuition to three months’ rent to this envelope.” I touched the manila with one finger. “And asking why the line ends where my signature begins.”

Amanda took a breath and, to her credit, tried to lay down a bridge. “Maybe we can look at other options for next year,” she said quickly to the table and also to me. “I’ve been reading about a public magnet program in our district. Tyler could apply.”

Mom looked at her like she’d betrayed a treaty. Jordan looked at her like she’d spoken out of turn on a podcast. Dad looked at the envelope like it might slap him.

I slid the loan papers across the linen back to Mom, slow and steady. “I won’t be co-signing,” I said. “Not now. Not later. Not for seventy thousand. Not for seventy.”

Jordan pushed back his chair, the scrape a kind of punctuation I’d been listening to my whole life. “Unbelievable,” he said. “Enjoy your little British fantasy. Some of us actually stick around for our families.”

“Some of us have been sticking around since we were fifteen,” I said. “And some of us bought a ticket.”

Mom flinched as if the paper could cut her from here. Dad’s voice softened in that way that once made me climb into the truck without complaining. “If you leave, you will be alone,” he said. “You think success means something without people to share it with, but it doesn’t.”

“I’m not alone,” I said, and for once, the sentence didn’t feel like self-pep; it felt like inventory. “I have friends. I have colleagues. I have a nephew who will know how to use video chat.” I turned to Amanda. “If you want to schedule weekly calls, I’ll be there every Tuesday at five. We can talk about dinosaurs. I’m very good at dinosaurs.”

She nodded, almost in spite of herself. The way people nod when a truth they hadn’t planned on liking sneaks around their defenses and sits in a chair anyway.

The waiter reappeared with dessert menus like peace offerings. Dad waved them away, his hand a flag. He reached for his wallet. I put my hand on his wrist and shook my head. “Dinner’s on me,” I said.

“That isn’t necessary,” he said, affront an old reflex.

“It is,” I said. “Let me buy us a clean exit.”

We waited while the card machine made its little song. I signed my name on the slip with a hand that was still steady. When the check was folded and taken, when the coffee cups were empty, when the napkins had been balled up into the shapes of surrender, we stood. I hugged my mother, who smelled like the perfume she has worn since before Jordan was born. She hugged me back stiffly and then a second longer because whatever else is true, she is still the person who taught me how to hold a spoon.

“I’ll send my address,” I said. “And a schedule.”

Dad nodded, then did the thing he does when he wants to prove he can be magnanimous: “Safe travels, son.”

“Thank you,” I said, and walked out of the private room into air that felt new because I finally intended to live in it.

It’s amazing how quickly your life shrinks into two suitcases when you decide not to drag everything with you. I sold the couch on a local app to a grad student who told me he was starting a lab rotation and looked at the stains like he had just learned the word “patina.” I donated half my closet and folded the rest into a space saver bag that made my shirts look like they were holding their breath. I gave the thrift store a stack of dishes and two lamps; I threw away the pajamas with holes; I kept the mug I’d bought the week after my last payment that said in thick black letters, DEBT-FREE.

My parents moved through the stages of grief for an adult son leaving: denial (Mom sent three job postings in our city within twenty-four hours), bargaining (Dad suggested I take the London role and “give it a year, then reassess”), anger (Jordan), then something that looked like acceptance (Mom asked for my flight number, Dad asked if the outlet adapters we bought in 1998 for a mission trip still worked in the UK).

Jordan didn’t call. He instead called my parents and told them to tell me he hoped it rained every day. Amanda texted and asked if I’d meet her for coffee. We chose a quiet place with mismatched chairs where nobody minds if you cry.

She got there first, stirring foam like it owed her money. “Thank you for coming,” she said, and transparency suited her. “Jordan doesn’t know I’m here. I wanted to say I’m sorry for the way that dinner happened. I told them it was a bad idea to spring it on you. They said you’d be more likely to agree in person.”

“It was an ambush,” I said.

“I know,” she said, and her shoulders loosened a fraction. “And…thank you for saying what you said. About math. About Tyler. I did research last night. There’s a public magnet program. We’ll apply next year. The tuition number—it’s ridiculous. We can’t afford it without…you. And we shouldn’t ask you. I didn’t see it before.”

“People don’t see water when they’re used to being fish,” I said, because my adviser’s metaphors had infiltrated me. “I appreciate you telling me. I don’t hate you.”

“I don’t hate you either,” she said, and it sounded like a confession and a correction.

We talked about Tyler’s art projects and the way he had started saying “actually” and then everything after “actually” as if it were from a peer-reviewed journal. Before we stood to leave, she said, “Even if Jordan and your parents don’t like it, I want you in his life. Will you FaceTime him every week? I’ll make it work.”

“Every Tuesday at five,” I said. “We can do dinosaurs. I can do trains too, but I’m better at dinosaurs.”

She smiled. “London has dinosaurs?”

“Better ones,” I said. “Some of them have accents.”

We hugged in the parking lot, that awkward, relief-braided hug you give someone you may one day learn how to trust again.

At the airport, the terminal smelled like wet baggage and coffee. The sliding doors parted, and there they were—my parents near the drop-off, looking like people who had made a decision in a kitchen and then decided to hold it together in public. Mom stepped forward first. “Amanda told us the time,” she said, as if apologizing for a trespass. “We couldn’t…just let you leave.”

Dad cleared his throat. He’d been practicing this speech, and it wore its practice like a suit. “Son, I’ve been thinking since that dinner. About…about what you said. About how we…about how things were. We should have helped you more.”

Mom’s eyes pooled fast the way hers always have. “We didn’t mean to make you feel…less,” she said. “We just…The truth is, you were so capable. We forgot capable isn’t the same as invulnerable.”

“It’s not about meaning,” I said gently. “It’s about impact.”

Dad nodded like someone who’d finally felt a word land. “We’re proud of you,” he said gruffly, and the ‘we’ for once was not a shield. “This—” he motioned to the glass and the flight boards and the unknown—“this takes guts. We’re proud of that.”

“Visit at Christmas,” Mom said in a rush, as if offering a bargain. “We’ll try to come. If you want us.”

“I do,” I said. “And thank you.”

We did that awkward triangle hug you see on commercials for airlines. Dad smelled like aftershave; Mom like that perfume again; the concourse like everything unfinished. “Go change the world,” Dad said. I rolled my suitcase toward security and looked back once not dramatically but to wave, which is a different kind of drama.

On the plane, I put my phone in airplane mode and stared at the little image of a plane crawling across a screen. Atlantically. Between the seatback pocket’s safety card and a plastic-wrapped blanket, the future sat and waited to be named.

Six months later, London had a way of making me feel new without making me pretend I wasn’t me. I learned the smell of rain on the Tube platform and how to stand on the right on escalators and walk on the left if you wanted elbows in your ribs. I learned to ask a barista for a flat white and mean it. I learned to say I’m film when I meant on camera during a pitch because that’s what the client needed to hear. I learned that you can build a life and send love through a screen and that the Thames at dusk looks like it knows things and is willing to share them if you’re patient.

Sulttera did not feel like a rescue so much as a proper trade. I gave them my hours and my skill and my insistence; they gave me a door and a budget and a team that learned my tells and started bringing me tea at the right time without making a fuss. I led a campaign that made the Financial Times write something that didn’t include the word plucky. It felt good to be written about without my family near the paragraph.

My parents came for a week at Christmas with a suitcase full of gifts and a desire to like everything. We took them to see lights that made Mom’s mouth go soft and to a pub where Dad discovered that a pint meant a pint and that he liked chips in cones served with salt. They didn’t mention the loan papers. They asked about work and my flat and whether I liked my neighbors. They told me about Jordan as if he were not an open wound—“He’s looking; he’ll land”—and I nodded because sometimes silence means yes, and I don’t want to fight you anymore.

Jordan did not come at Christmas. He sent a card that said Happy holidays in his wife’s handwriting and had a photo of Tyler wearing a sweater with reindeer and a grin that would make you say yes to anything he asked. On the back, Amanda wrote an update about the magnet school and a thank you for our Tuesday dinosaur calls. Tyler shouted into the phone on our next Tuesday that London looked like a movie and that he wanted to ride a “double bus.”

I emailed my new address to my parents. I sent them a link to the campaign article only after Dad sent me a photo of the print version folded open on our old kitchen table. The subject line read simply: Proud of you.

I printed it and taped it inside the cupboard door where my spices live. Not for guests. For me.

Sometimes at night, I stand at the window and watch the city do the trick every city does: look important enough that it makes you feel like not wasting your time inside it. I think about the kid in our kitchen under the glow of a too-large TV going quiet so other people could enjoy what they bought themselves. I think about the boy on a porch holding a wallet with a ticket in it. I think about the man at a table with papers pushed toward him, choosing himself not like a weapon but like a muscle finally ready to lift something worth lifting.

Tyler’s face fills my laptop on Tuesdays, and sometimes Jordan leans into the frame, not speaking, just looking. I say hi anyway. He nods. It’s a start. Or it’s nothing. Maybe those are the same thing at the beginning.

When the kettle clicks off, I pour water over a teabag and stand very still while small leaves give the room a smell I didn’t grow up with. I think about how expensive the word no felt the first time I said it in a voice my parents had to recognize. I think about how cheap yes had made my life when I bought it for the wrong reasons.

What I feel most often is not triumph. It’s relief. I’m not climbing out from under anything. I’m just walking in a city I chose with a debt balance that reads zero and a family column that finally looks like something I can afford.

And if Tyler asks me, as he always does at minute nine of our Tuesday call, “Uncle Larry, when are you coming to visit?” I say “Soon.” And I mean it, because now I can choose when soon is for me.

Part III

Gate 22 looked like every gate in every airport—stained carpets the color of resignation, a line at the charging posts, a couple attempting to have a meaningful argument on whisper volume. The departure board ticked LONDON in amber. I had the particular calm that shows up when you’ve already paid for where you’re about to go.

My phone chimed. Dad.

I almost let it roll to voicemail, not out of spite but because the moment felt correctly framed: ticket in my wallet, boarding group on my screen, life arranged in two suitcases and a carry-on that squeaked. But the ringtone I’ve had since college kept playing its cheerful lie, and the world had been generous enough to hand me one clean goodbye already—the curb, the hug, Go change the world, son. After that, avoiding the call felt like greed.

“Hey,” I said, eyeing the line forming around the metal stanchions. The agent scanned passports in the practiced rhythm of a metronome.

He didn’t start with hello. “I wanted to catch you before you board,” Dad said. I could hear the kitchen in the background—the tick of the cheap wall clock near the pantry, the chair that always scraped because it had lost one felt pad, the sound of my mother opening cabinets like she was looking for salt and found old regrets instead. “Two minutes.”

“Go.”

“I’m not calling to argue,” he said. “I need to say a thing. More than the thing at the curb.”

There are sentences you want to resist because you’ve wanted to hear them for so long. I said nothing and let him try.

“We miscalculated,” he began. “We saw you…competent, early. We talked at the table about how good that would be in the world.” He snorted in self-disgust, a sound I’d never heard on him. “We turned your strength into an excuse to test it. We confused how impressed we were with you for not needing to show up. We confused Jordan’s needing for our…duty. We made a bad algorithm and called it parenting.”

A gate agent announced pre-boarding for passengers needing extra assistance. A toddler shrieked and then announced “I am okay now!” to the gate, and the entire boarding area laughed.

“I can’t fix those years,” he continued. “And I won’t insult you by pretending we can. I want to fix the part where we keep assuming you’ll pick up what gets put down.”

“Thank you,” I said carefully. A boarding group name flashed, not mine yet.

“I also called because your mother is sitting at the table with the manila envelope,” he said, voice lowering like a confession. “And she asked me to bring it back up, and I told her this is what change looks like: not asking. I need you to know I said no for both of us before I called you.”

I let out a breath I hadn’t noticed holding. It made the cheap plastic seatback across from me look more hospitable.

“You don’t owe me anything,” I said. “But I appreciate that.”

There was a pause long enough that I pictured him at the table looking at the very chair I used to sit in after reporting cards and watching his face for reaction. When he spoke again, it sounded like a declaration to the linoleum. “We will help them. We’ll do that math. It will be our signature if there’s signing. You owe your nephew dinosaurs on Tuesday.”

“Those I can afford.”

Someone sat in the empty chair to my left, gave me a tight smile, and opened a Tupperware that smelled like onions. I looked toward the window: one of those planes where you feel like you can see the whole continent of your new life just by squinting at an engine.

“Son,” Dad said, softer, like he’d found the tone that meant he was overplaying nothing, “your mother wants to be part of this in a way that doesn’t look like guilt. She wants to plan a week at Christmas that involves Hyde Park and her shoes being wrong for it. I want to tell you again I’m proud. And I want you to know I understand that ‘family’ is not a debit you owe us forever because we gave you a last name.”

Someone dropped a suitcase and swore quietly. The agent called Business and Priority.

“London’s boarding,” I said.

“I know,” he replied. “Text when you land. Save your battery for now.”

We hung up. I looked at the glass, at my reflection with the cheap neck pillow already out of the plastic like an amateur move. In the ellipse of that moment—Gate 22, group numbers rising, a father finally learning a language too late but still trying to speak it—I had the odd, steady thought: I didn’t need their apology to go. But it made taking off feel less like escape, more like departure.

London at first was a map I kept trying to put in English. The Tube felt like a series of polite punches—stand on the right, walk on the left, mind the gap between who you’ve been and who you can be. My flat was a one-bedroom with crooked floors in a brick block that had seen things and kept them. The Thames looked like it was always doing math in its head and finally content with its sums. Sulttera dropped me into a team that spoke ambition fluently; they liked that I didn’t flinch when deadlines tested decency and that I said, “What does this actually do for the client?” in rooms where people were used to being impressed by each other.

I bought a coat that did not pretend rain was avoidable. I learned to order a flat white without sounding like a tourist. I discovered there is a particular kind of human miracle in standing next to an ancient painting on a lunch break because it costs you nothing but the time you were going to give to your phone anyway. I put a tiny postcard on my fridge—Turner’s “Rain, Steam and Speed”—like a private joke between me and past versions of myself.

Tuesday calls with Tyler began as chaos and became ritual. He’d come to the screen holding a toy and six facts about it. “Dinosaurs lived a very long time ago,” he informed me early on, wrinkling his nose. “Before Paw Patrol.” I told him about theropods and why T-Rex couldn’t clap. He told me about magnets and pudding. Sometimes he asked where the plane was in London and I turned my camera and pointed vaguely at the sky. Week by week, the little squares on my screen became part of a new calendar, one that made being an ocean away feel more like a bridge you cross on schedule.

Amanda kept her promise. She made space even when it meant telling my brother, “Your son wants to talk to your brother and I’m making that happen.” Once or twice Jordan leaned into the frame and said “Hey” into his mug. I said “Hey” back. It wasn’t healing. It wasn’t nothing.

Work poured meaning into me and asked politely for its return. The first campaign I ran for Sulttera won an industry award no one outside the industry cares about and made exactly the kind of clients we wanted to care. My team—weird, young, meticulous—bought me a cake that said, LARRY — ON BRAND. I hung the plaque not near my desk, but near the door to the conference room. This is what we can do, it said. It doesn’t change who we are.

Autumn slid into the Thames like the city had decided it couldn’t be bothered with a big gesture. I learned the names of my corner grocers. I became a regular at a pub that made chips correctly. The bartender learned I prefer a half pint with dinner and nodded—an acknowledgement, not a performance. Paula from accounting set me up with a friends group that ran the Heath on Saturdays; I discovered you can make a life by saying yes to people you wouldn’t have met if your parents had chosen different columns twenty years ago.

At night, sometimes, I still opened my bank app for the joy of seeing zeroes where there ought to be and none where there ought not. The number that felt like a roommate had left, finally, and the quiet in the flat was the good kind.

The first Christmas they came, they were cautious, like tourists in a museum of my adulthood. Mom brought a tin of cookies and a container of something gelatinous and insisted on seeing “where the work happens.” I showed them an office too modern for my father’s idea of productivity and he hid his discomfort by asking precise questions. “What is this…scrum?” he asked, relieved by a task. I put him in a swivel chair and watched him learn how not to hate it. We stood on Tower Bridge and he said, “I can’t believe this is here.” He meant me.

Mom took Hyde Park in foolish shoes and refused to complain. After we all laughed at her sinking in the grass, she squeezed my arm and said, “Thank you for not staying angry.” It surprised me because I hadn’t decided not to be. The anger had just found less room to live in the work of living.

We didn’t mention the envelope. We didn’t need to. A better sign: my parents insisted on paying for dinner twice; I let them.

They left with a vase from a market and my mother’s new favorite phrase—“queue properly”—and a map that drew a straight line from our flat to two museums to a bakery Dad declared “obscenely simple.” They also left with a schedule for Tuesday calls and a promise to figure out FaceTime angles that didn’t make their foreheads the main character.

A thin card arrived from Jordan in January. No apology, no twist of the knife. Happy holidays in his wife’s hand, a photo of Tyler with a sweater featuring reindeer that insisted on joy. On the back, Amanda had written: We applied to the magnet program. He got in. Thank you for saying no. I pinned the card on the cork board by my desk under my rental agent’s magnetic business card. Some things you want near each other.

Work made me tired in a good way. A campaign lost persuaded me I wasn’t lucky; a campaign won persuaded me I wasn’t only stubborn. I hired a junior strategist who used we even on days he had done everything alone and then gave him credit in rooms where no one looked past my tie. The day I heard my own name in a hallway from two people who didn’t know I could hear them—“…Larry said—” “—no, he listens first—”—I felt the oddest burn behind my eyes. I went to the bathroom and let it be what it was. You can be proud of being the man you worked at becoming without congratulating yourself like you planned it.

In March, Sulttera pitched a global client so big it made even the senior partners stand up straight. We didn’t get it; then we did. They called my name and handed me more responsibility with one hand and an expense policy with the other and laughed. I ran the kickoff meeting holding a notebook with my own checklist in the back: don’t talk first; know the problem not just the brief; remember the client watches how you talk to your team.

I made it through six months without buying a coffee machine for the flat. Then I bought one and stood in front of it like someone visiting a monument to foolishness. It wasn’t about coffee. It was about making a decision based on want, not need. The first cup did what all victories do: it tasted like relief with a hint of future.

The city gave me a spring like an apology for the winter. I took the apology and went for walks.

I committed to visiting home in June. Not to prove anything, not because I’d run out of London. Because a trip home you’re choosing has a different gravity.

They picked me up from the airport and Dad didn’t say a word about how flying makes a man soft; he just asked about time zones like a human. Mom had “queue properly” ready and used it wrong in the rental car and we laughed. The house smelled like lemon and a memory I was no longer allergic to. Jordan didn’t come over the first night. He texted Amanda Sunday morning: “Bring Tyler to Larry’s.” The message made its way to me through the family switchboard like a relic.

Tyler ran into me like a small car with bad brakes. “London Uncle!” he yelled. He opened his backpack to show me a stack of drawings featuring planets and a stick-figure bus. “Double bus!” he shouted, correcting not in words but in exuberance. I took him into the backyard and we became dinosaurs in the way men become things for children: unselfconsciously, loudly, forgivingly. Jordan watched from the patio door, arms crossed.

When the kid collapsed into a satisfied heap of grass, Jordan came outside, hands in his pockets. He stared at the fence for a second like it had wisdom. “I said some things,” he started.

“I said some things back,” I offered.

He nodded. “You were right about the math.” He blew out a breath. “We’re not doing the school thing. It was ridiculous.”

“I’m glad,” I said. “For you. For him.” I didn’t add for me, because one of us needed the dignity of not needing to be included in that part of the sentence.

He turned his head, reluctant, the way people do when their pride is trying to talk them out of being decent. “Amanda said you meet him every Tuesday.” He smirked then, a ghost of the kid who could sell anyone anything. “You’re better at dinosaurs than I am.”

“Practice,” I said.

He put out his hand. We shook the way men do when they’re trying not to lose their footing: twice, firm, nothing dramatic. The shake was its own apology and its own refusal to keep reviewing the past’s invoices.

We ate spaghetti that night without anyone narrating effort or debt or the due dates of old mistakes. Mom asked Tyler about school, and he said, “I like recess.” Dad told a new fishing story, mercifully shorter. Jordan asked about my campaign in a way that wasn’t about being impressed; it was about being interested. I told him enough. He took it in. We did that until it felt like a thing we could do occasionally.

The last boundary came on a Sunday two months later, after I’d gone back and the camera called me home for an hour. Mom texted that Jordan had found a different school that “only” required a forty-thousand-dollar “endowment contribution.” She wanted to know if I could gift five or ten toward it as “a gesture.”

London light made squares on my floor. I stared at the text long enough that my tea went cold. Then I typed: I can give a smaller gift directly into a 529. That’s a gift for Tyler with no strings—money I control, no loans, no signatures. If that works, I will do it. If the requirement is a contribution to a private school endowment and my name on a paper, the answer is no.

She replied after an hour: Your father says: That is generous. We accept that. We love you.

I smiled because sometimes progress looks like a sentence that would have been impossible a year ago. I set up the 529 in fifteen minutes and sent the confirmation in a screenshot at the speed respect requires. It wasn’t about the number. It was about the direction. I picked the road that let me be generous and still sleep.

On a Tuesday in September, the campaign I’d led won an award that people outside our world don’t care about. We all went to a bar with bad lighting and hugged too hard and promised to stop checking emails for one hour. My phone buzzed anyway. Dad: photo of a newspaper article where my name had become a noun. Proud of you, he wrote again, not a subject line this time but the entire message.

I wrote back: Thanks. Tuesday dinosaurs in ten minutes. He sent a thumbs-up that looked wildly out of place next to the words Proud of you and somehow perfect.

I walked home along the river and felt that precise sensation that only emerges when a life’s math works out: the columns might never be equal, but the ledger balances. I had learned, too late and just in time, that family doesn’t entitle you to each other’s signatures. It entitles you only to the chance to become people worth inviting into rooms where you’re making your next life.

Back in the flat, I set my laptop on a stack of books that made me look less like a person dreaming into a webcam and more like a person with a sense of furniture. The screen lit. Tyler filled it with a drawing of a T-Rex that seemed to be smiling. “Guess what,” he said.

“What.”

“Dinosaurs didn’t clap because they didn’t need to. They roared.”

“I know a few rooms like that,” I said.

He roared. I did, too, and the city outside my window kept doing what cities do—the everyday miracle of people deciding and then living.

Later, alone, I poured boiling water over a tea bag and stood the way you stand when you have nowhere to be urgent. The cupboard door was still open. Inside, taped above my spices, was the printed article my father had sent, the subject line included because it had felt like part of the text. It hung next to my grocery list and a receipt for the first coffee machine I’d ever bought for myself. I touched the paper with one finger, not superstitious, exactly, but grateful.

At Gate 22, months ago, a phone had rung and a man’s voice had tried on a new language. It had faltered, then landed. That was not the reason I boarded. I boarded because for once my “no” had been for me. The life after didn’t change that. It just proved that a ticket can be a boundary and a beginning at once.

I closed the cupboard. The latch clicked. Somewhere in the flat above mine, someone laughed at a sitcom. On my screen, a calendar reminder popped up for a call with a client in the morning, and underneath it, in a different color, Tuesday — Dinosaurs.

The future, despite everything we all tried to make it, was suddenly very simple: say yes to what you can live with, say no to what buries you, buy your own ticket, and keep your promises on Tuesdays.

THE END

News

I CAME HOME UNANNOUNCED ON CHRISTMAS EVE. FOUND DAUGHTER SHIVERING OUTSIDE IN 31°F, NO… CH2

Part I I didn’t plan the surprise like a movie. There was no orchestral swell when I turned into our…

My Husband Poured Hot Coffee on My Head in Front of His Mother and Our Son for Refusing to Pay for CH2

Part I I still have the receipt from the night I should’ve known better—curled thermal paper, $8 Uber to a…

Rich Wife Hid A Camera To Catch Her Husband With The Maid… But What She Saw Shattered Her World. CH2

Part I The receipt was not much to look at—cheap thermal paper curled like a leaf left too close to…

I Thought Letting My Ex See the Baby First Was Sweet — Now My Husband Walked Out on Me at the Hospit CH2

Part I The day we argued in the nursery, the paint was still tacky on the baseboards and the crib…

My fiancé recoiled when I mentioned morning sickness at our baby shower and loudly announced… CH2

Part I I used to think gift wrap solved everything. It made chaos pretty. It turned a tangle of receipts…

My parents called my son a LOSER and banned him from Christmas… CH2

Part I I was making lists—the kind you make in December when you’re trying to pretend the holidays are logistics…

End of content

No more pages to load