At my graduation dinner, everyone was laughing until grandma smiled at me and said, “I’m so glad the $1,500 I’ve been sending you each month helped out.” I froze. “What money?”

Part One

The clatter of forks and the clink of champagne flutes braided into a polite hum that didn’t belong in our narrow dining room. My mother had pinned borrowed eucalyptus to the chandelier and draped gauze down the banister like we lived in a magazine spread instead of a two-bedroom house that smelled faintly of lemon cleaner and the furnace turning over. A banner arched over the fireplace: CONGRATULATIONS, KALA! in glittering cardstock, each letter taped carefully so no paint would peel when my father took it down later and folded it for “next time.” The good plates gleamed. The napkins were folded like tulips. It was all, I realized, for show.

“Kala, sweetheart, stop hiding in the hall and come let us adore you,” my mother called, sweetness calibrated precisely to satisfy guests and silence me. She swept toward me before I took three steps, arms narrowing around my shoulders as if an embrace could keep me where she wanted me. “You look lovely,” she said to the room.

Vivian—Grandma, to me—cut through with a smile that still made my chest feel like a doorway thrown open. “There she is,” she said, standing despite her bad hip and beckoning me into a hug that smelled like violets and paper. “My graduate.”

For three seconds, the world was only the warmth of her coat and the way her cheek pressed into my temple. Then my mother’s hand arrived—firm on my wrist, tugging me toward the living room where the tray of toast glasses waited. Cameras were already poised. Cousins were smiling for social media. My father, strokes from retirement away from considering himself a patriarch, was lighting the fat pillar candles my mother only arrested for company.

“For our Kala,” he said, raising his flute, voice slipping into his gentleman tone. “Who has made us proud by finishing with honors, reminding us that work does indeed pay off in the end.”

“And sacrifice,” my mother added brightly, squeezing my fingers just enough to make me feel them. “We’ve all tightened our belts these last few years so she could fly.”

I smiled and tasted metal. We’re tight this month, Kala. Maybe next semester, Kala. You know how things are. A braid of sentences I had wrapped around myself for four years, trimming everything I wanted to fit inside it. I wore three outfits on rotation until the hems frayed. I said no so many times I forgot how yes sounded.

Conversation resumed with the soft purr of approval. My uncle launched into a story about the commute into the city. My cousin explained her pre-law internship like she had written the Constitution. Vivian reached for her fork, eyes bright and moist in the way proud grandmothers get when they’ve already cried once in the bathroom and told themselves to hold it together for the cake.

“I am,” she said, settling her napkin with the air of someone who has decided something. She turned to me, the room shrinking to just her and my face. “I’m so glad the fifteen hundred I’ve been sending you each month helped out, darling. Didn’t it make the difference it was meant to?”

I caught the fork before it reached my mouth, the tines a millimeter from my lip. The flame-shaped banner over the fireplace wobbled in the corner of my eye.

“What money?” I asked, too fast, too even. The room clicked into silence. It felt as if someone had slid a glass box over us.

“The deposit,” she said, not breaking eye contact. “Since September that first year. Fifteen hundred on the first, so you wouldn’t have to work yourself into the ground.”

Air thinned. Sound washed out. The only thing left was the look that passed between my mother and father: the flash of white at my mother’s throat, the muscle in my father’s jaw jumping like a trapped moth.

“There must be…” My mother’s voice broke on a practiced laugh. “Mother, really—must you—there’s been a mix-up. Perhaps later—”

“I never got it,” I said. My voice returned to me from the mirror of glasses and shiny plates, strange and certain. “Grandma, I never received a single deposit from you.”

Vivian’s eyes darted to my mother. “Elaine?”

My father recovered like a man stepping out of a ditch and pretending he had meant to. “Probably a bank error. We can sort it tomorrow. I’m sure your mother has the records.”

“I have every confirmation,” Vivian said. “Every single one. Four years of them.” She rubbed her thumb over the edge of her napkin. “I wanted to make sure I did at least one thing right by my granddaughter.”

My stomach gave a slow, furious turn. Twenty-four months times fifteen hundred times four. Seventy-two thousand. Numbers I used to hold job offers against flashed and reassembled into four years of ramen, panic attacks I couldn’t afford a therapist for, two weeks of walking to campus because my car died and my parents were “tight.”

“You told me we were struggling,” I said. I wasn’t sure which of them I was speaking to anymore. Both of them. “You told me there wasn’t anything to spare. You told me maybe we could help with books next term if the bonuses hit or if Dad’s client paid finally or if the air-conditioning didn’t go.”

“Kala,” my mother said, reaching. I flinched. Something in her face cracked, then shifted into something softer and more manipulative. “We were protecting you.”

“From what?” The glass in my hand shook. “From money? From the ability to breathe? From not fainting in the middle of Professor Long’s lecture because I hadn’t eaten anything but coffee and pride in 24 hours?”

“Perhaps,” my father cut in smoothly, “we should take this in there.” He gestured toward the kitchen like a man offering a drowning person a different puddle.

“No,” Vivian said. “We will not move to the theatre you are comfortable in.” She slid her chair back with a sound that made people start. “Kala,” she said, her voice soft again. “I’m at the Parkside, room 312. I have my records. Come when you like.”

She left her wine untouched and her fork aligned perfectly with the edge of her plate, stood up straight like a woman who had decided the rules were hers now, and walked out of my parents’ house.

The party limped through the motions. People gossiped in the hallway in voices like moths’ wings. The banner curled. My mother disappeared into the bathroom and emerged with eyes she forgot to rinse properly. My father refilled glasses that didn’t want it. Cake was cut. Everyone pretended sugar could make anything stick together.

After the last guest left—after my mother blew smoke toward the patch of wall where Vivian had once given me a dictionary instead of a doll (“You’ll use this more”), after my father stacked plates like a man disarming landmines—I went to my room, closed the door, and lay on my back staring at the glow-in-the-dark stars my father had stuck to the ceiling when I was ten and he still remembered birthdays.

At five, I got dressed. At five-ten, I wrote a note for show and left before anyone could decide I didn’t need to.

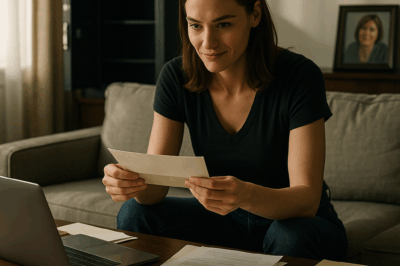

Vivian opened the hotel door fully dressed, hair pinned, coffee steaming. “Some habits,” she said, smile softening everything. On the table: two plates, two cups, a small mountain of receipts secured with a binder clip.

“I trusted Elaine,” she said, tapping the stack. “I sent a check the first month. She cried—tears real enough to wet my knuckles—told me you were so grateful. After that, I set up the transfer.”

“I—” My throat closed over words that didn’t know where to land. “Can we…show me.”

She did. September through August, a line of generosity like a breath held too long. $1,500. $1,500. $1,500. Four years. Then the high school checks before that—$500 a month into an account I had never seen, starting junior year because “college creeps up,” she said now, the regret audible. “I was trying to be what my mother wasn’t,” she added, a shadow crossing her face. “Present. I still found a way to be absent.”

“It isn’t on you,” I said, too quickly. “You did what you were supposed to. They—”

“—did what they always do,” she finished, mouth going tight. “We’re going to fix this.”

We began with the bank. A woman with a bun so tight it looked like a discipline asked me to verify my street, the last four of my social, my first pet (“Lark”), and then said cheerfully, “And your third account?”

“My…what?” I looked at Vivian. “No, I only have—”

“Checking and savings and the joint with Elaine Winter,” the woman said. “It’s been open since you were seventeen. It has signatory authority on both ends.”

“You can’t open a joint with a minor,” Vivian said, her voice going a kind of cold I hadn’t heard before.

“Power of attorney,” the woman chirped. “On file. It says temporary.” Keys clicked. “And expired.”

“So they had access,” Vivian said. “They always had access.”

I hung up and texted my cousin Marin. Please call me when you can. It’s about Grandma’s money. The call came in three minutes.

“I tried to tell you,” she said without hello. “They did it to me too with Grandpa’s education fund. Called it ‘managing’ so your future wouldn’t be squandered. Spent it on granite.”

We met that afternoon in the coffee house where I had spent so many weekends disassociating over mochas. She said your independence made them look bad. That your ‘expensive taste’ was selfish. She told people you didn’t like us. She said we were the ones isolating you.

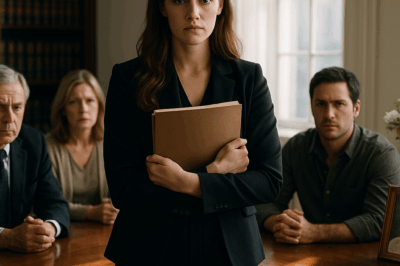

I made a list. I brought the list to Vivian’s attorney, a man whose office smelled like leather and old victories.

“This is theft,” he said mildly, turning over documents with meticulous fingers. “This is fraud. This is forgery.” He lifted his gaze. “And—though this isn’t the term courts use—this is abuse.”

I swallowed. Naming draws blood; it also cleans wounds.

“We’ll need more,” he said. “A full accounting. The joint paperwork with the forged signature if we can get it. Any emails. A log of your own attempts to address financial needs and their responses.”

I produced my notebooks—fifteen years of dates and amounts and comments scribbled in margins:

HEAT BILL PAST DUE. Mom says “we’re tight” again. Dad says “bootstrap”. Bought space heater for $22 from thrift store. Wore coat to bed for three nights.

ROOT CANAL. 12/14. Mom said ibuprofen and prayer.

NORTHWESTERN SUMMER. $3,000 scholarship. Declined. Mom said “we can’t be greedy.”

Vivian blinked hard. “I sent three thousand that June so you could go. Elaine told me you’d changed your mind.”

I took that memory in my hands and rotated it. I watched it become something else under different light.

The night my mother cried on the kitchen floor after one of my questions (“Why do I owe the house fund when I earn minimum wage?”) was no longer about the tragedy of motherhood. It was about diversion. The afternoon my father announced he was giving the living room “good bones” instead of giving me $190 for a biology lab fee became less about aesthetic taste and more about misdirection. The time my mother told me my birthday check from Grandma “bounced” felt like asphyxiation. Now I saw the hand over my mouth.

When I confronted them—at a coffee shop packed with people and foam and the smell of cinnamon because I knew if I went to their house I would be a little girl again—they performed like actors summoned by line.

“We were protecting you.”

“You were too young to manage.”

“Money like that can ruin a girl.”

“You don’t understand the stress we’ve been under.”

“You’re tearing this family apart, Kala.”

I recorded their explanations and left them on my attorney’s desk like evidence and old bones. Vivian changed her will on the walk from the filing cabinet to her car. She removed my mother with a hand as steady as a surgeon’s and put my name in ink that did not tremble.

Rec—my steady, careful boyfriend of eight months who believed in balanced budgets and called all his plants by name—listened and said, “Are you sure it’s worth all this drama?”

“That’s the thing about drama,” I said. “It usually begins when the curtain falls.”

He left like a man who had never once worried whether heat might be shut off. Vivian poured tea and said, “Some men are built for slipper weather. You need storm boots.” Marin showed up with pizza and a binder of her own. My high-school English teacher, Miss Reynolds—the one who had pressed crisp dollars into my palm on days my lunch card “mysteriously” showed zero—told me she had called CPS when I came to school coatless in December. Nothing came of it. “Your mother was very convincing.”

The judge at the emergency hearing was not convinced. She looked at my parents’ lawyer over her glasses like a disappointed aunt and said discovery would proceed, forensic accounting would be ordered, and attempts to paint this as “misunderstanding” would be met with notes from her clerk.

In the lobby afterwards, my father approached like he was pushing a mower uphill. “Let’s be civil, Kala. Let’s settle.”

“Confess,” I said. “Account. Apologize without the words ‘if’ or ‘but’.” His jaw worked.

My mother tried the letter that night—the twenty pages of sorrow and I was under his thumb and your grandmother always loved you more and forgive me because I cry the right way. I read it, then burned it in Vivian’s fire pit with her hand on my back. We watched the flames take the looped letters. When the last ash lifted, the air felt lighter.

Two months later, the forensic accountant’s report landed like a piano dropped from a window. The money had gone the way we thought it had—with detours we hadn’t imagined: a “wellness retreat” with heated pools and “inner child work” in Arizona, a botox package my mother had told me was a gift from her friend, the down payment on a boat my father took to the lake three times and called therapy. There was a ledger entry labeled KALA EMERGENCY with the note “She wants therapy. Tell her God.”

They settled. They agreed to repay the full amount with interest, to fund a scholarship account ringed with protections, to make a public admission. “You can keep your money,” I told Vivian later that night. “I want the public part.”

They balked. Then they understood the alternative was a trail of paper that would outlast their charming sighs. They read the statement in front of the judge. They didn’t choke. I didn’t clap.

With a portion of the settlement, I rented my own place—a small apartment above a bookstore downtown, where the owner called me “kid” and left a light on in the stairwell after late shifts. Then, because restlessness paired with relief produces strange clarity, I bought a microphone. I started talking into it once a week.

“Inheriting Silence,” I called the podcast, people sending voice memos from laundry rooms and parked cars: He made me sign my car over at nineteen. She told me the joint account was for college and then paid for my sister’s wedding. They said I was dramatic when I said I was cold. The emails started: I thought it was normal to hand over my tips. I thought love was making myself small. I thought I deserved it. We told each other otherwise.

The university invited me to speak. I stood at a podium where I had taken notes with cramped fingers and no coat and said, “Independence you have to earn is control. Control dressed like care is abuse. Abuse doesn’t need bruises. It prefers ledgers.”

A father with careful hair waited after the Q&A. He said he had stopped speaking to his daughter five years ago when she moved to a city he didn’t like with a partner he resented. “I thought if I froze the fund,” he said, twisting his wedding ring, “she’d come home. I didn’t realize I was telling her she had to choose between her life and me.” He cried in the hall next to the vending machine. He let me hug him. He went home and wrote his daughter a check and a letter that didn’t say if.

In July, my father’s mugshot appeared beneath a headline about corporate embezzlement. I made tea and took a shower and then recorded an episode about what happens when the strategy you learn at home becomes your business plan. He got five years, eligible for parole after three. My mother wrote again. The letter was different. It did not cry. It did not defend. It did not ask. I put it in the fire. The flame carried it to a place where it could not unspool me.

By fall, Vivian and I had a ritual. Morning walks around her block, her arm linked in mine, the wrought iron fences of her Victorian neighborhood humming with old stories. Afternoons at the long table facing the garden, her working on her own punctuation of a life; me drafting speeches and letters and chapter headers: Inheritance is more than money. Boundaries are not meanness. Love without respect is control wearing perfume.

We founded a small non-profit with my therapist—Quiet Funds—where we bought coffees and sat with kids who wanted to open accounts without their parents, where we told women they could say no to cosigning, where we wrote scripts like talismans:

Script for “No”: “I will not give you my login. It’s my account.”

Script for “Guilt”: “Love and money are separate. If you attach them, you’re not protecting me; you’re binding me.”

Script for “Forgiveness”: “I accept your apology. My boundaries remain.”

A newspaper ran a feature. People sent $18 and $36 and $100 with notes that said, “For the kid who thinks she’s dramatic.” A foundation doubled it. We taught a workshop to a room full of social workers who had never learned how to spot the pattern in the numbers.

The day the court approved the repayment plan, I drove home past my parents’ house out of curiosity. The azaleas needed pruning. The banner had been taken down a long time ago. I parked across the street, hands on the steering wheel long after the engine went cold. My mother came out to retrieve the trash can, looked up, saw me, and raised her hand like surrender. I didn’t wave back. Some doors close kindly. Some close like a gavel.

On the first anniversary of the dinner where my grandmother ripped a tablecloth off a lie, I sent Vivian a cake with violets made of sugar and Thank you piped in a hand that shook. I went to the bookstore downstairs and bought three copies of a memoir that had saved someone else. I realized that my life had shifted from earning to telling; from surviving to writing. That I had become the person my fourteen-year-old self had prayed into her pillowcase for: a woman who could stand in a room and say, “No.”

That evening, as the cat kneaded a spot into the cushion next to me and my inbox filled with strangers beginning letters with Dear Kala, I thought I was crazy until…, Vivian called.

“How’s it feel,” she asked, “to be the one laughing at the dinner table for once?”

I thought about it. “Like oxygen,” I said at last. “Like someone opened a window.”

“And your parents?” she asked, light but not unkind.

“Still convinced the draft will blow out their candles,” I said, and we both laughed, a sound that did not apologize for existing.

Epilogue

At a conference on ethics and inheritance, I ended my talk the way I end the support group meetings, with three questions I wish someone had asked me in a dining room lit by candles and expectation:

What would you sacrifice to reclaim your stolen dignity?

What would you build when no one else is holding the tape measure?

And how loudly can you live when you finally breathe?

In the front row, a grandmother squeezed a girl’s hand. Somewhere, a mother closed a letter and decided not to send it. Somewhere, a daughter bought herself a coat.

Later that night, I sat at Vivian’s long table facing her garden. The evening smelled like mint and old wood. I opened my laptop to a blank page and wrote: I didn’t lose a family the night my grandmother asked a simple question at a crowded table. I found the one person I needed to be. And then I made room for everyone who wanted to meet her there.

When I clicked save, the tiny whir of the hard drive sounded like a laugh held too long, finally exhaled.

Part Two

The first cold snap came early that year, a thin silver skin over the puddles and the breath of the city rising like a congregation of ghosts. I hung a wreath on the blue door of my little house and stood on the stoop long enough to let the wind fret my hair and tuck itself into my jacket. Across the street, Mrs. Schulz wrestled a bag of rock salt up her stairs; I waved and she waved back with the hand that wasn’t fisted to her hip. Life had tilted into a new normal—quiet, self-authored, ringed with things I chose because I wanted them rather than because they were cheapest.

Inside, the radiator ticked like an old watch. Vivian sat at my kitchen table in her wool coat, a scarf draped in perfect loops like she’d practiced, a stack of printouts before her. She’d taken to emailing me things she thought the podcast could use—studies, op-eds, letters from other grandmothers who kept receipts—and then bringing a hard copy anyway, because paper had a way of resisting deletion.

“Listen to this one,” she said, tapping a page. “A woman in Des Moines who convinced a judge to appoint a neutral trustee for her son’s college account because both parents had—what’s the phrase—conflicts of interest.” Her eyes glinted. “They based the order on a brief that cites your forensic accountant’s report.”

I laughed into my coffee. “We’re footnotes, Grandma. The revolution is unglamorous.”

“Footnotes,” she said, deadpan, “move the story along.”

We were making turkey soup with the carcass of a bird we’d roasted for a Friendsgiving in my living room, the table leaf extended and saucers mismatched on purpose, my house full of my kind of noise. Marin had driven in with a pie and an apology she didn’t owe anyone. Julian, bewildered but game, had peeled potatoes like they might reveal a deeper truth if handled correctly. Amy had taught Lily—sixteen and newly mouthy—the secret handshake of women who survived households of careful hunger.

When the mail slot rattled, I assumed it was circulars and holiday catalogs. Vivian went to fetch it anyway—the woman cannot abide papers on the floor. She returned with an ivory envelope addressed in a loopy hand I knew before my body did.

“Elaine,” she said, and handed it to me like a nurse might offer a sedative: useful, potentially dangerous, entirely optional.

I set it beside the salt cellar and went back to stirring. We had rules, ones Amy helped me carve and sand and varnish until they gleamed: I did not read my mother alone. I did not read her when tired. I did not read her in my bed. And I did not mistake reflection for repair.

It wasn’t until after we’d eaten and washed the dishes and Vivian had taken the train back to her oak-lined street that I slit the envelope with a butter knife and slid the pages free.

It was not the letter I’d braced for. There were no grand gestures, no collapses into I’m worthless as a bid for power, no curation of detail to position herself under an angel’s wing. It was dated, numbered, notarized. The handwriting was neat like she had practiced slowing down.

I have been in therapy for four months, it began. My therapist tells me to confess to a wall until the wall is bored. She says the point is not to elicit forgiveness but to practice telling the truth without lacing it with need. Here are three things that are true.

1) I signed your name when you were seventeen. No, I did not ask. Yes, I knew it was wrong. I told myself it was temporary. It was not. I changed the story in my head so many times that I started to believe it.

2) I told my mother—the one who lives in your bones and makes violets smell like safety—that you didn’t want her money. That you didn’t have time for her calls. That you rolled your eyes at her gifts. I made her grief look like your ingratitude. That is unforgivable.

3) I am jealous of how easily you make strangers feel seen. I have always wanted to be the one the light follows. It’s ugly to write and uglier still to own. But the truth is, I built a house where only applause was love. I am tearing it down, brick by brick. I don’t know if there will be anything left when I’m done. That isn’t your problem to solve.

I won’t ask for anything at the end of this letter. Not forgiveness. Not lunch. Not a reply. If you ever want proof that I am doing the work, you can ask Amy whether I show up. You can ask my group. You can watch me sit in discomfort and not bolt.

Your father has asked me to visit him in prison. I have not decided. For now, I am busy learning how not to perform pain.

It should have landed like a rescue flare or a curse. Instead, it sat pragmatically on my table, smelling faintly of the inside of a leather bag and the ink at the DMV. I read it twice. I did not cry. Then I put it in a file labeled Documentation and texted a photo to Amy with a single question mark.

Looks like a Step Four letter, she wrote minutes later. Good for her. Not relevant to your boundary unless you want it to be.

I went to bed and slept like someone who had handed the night a leash and told it to sit.

In January, a state representative’s assistant slid into my podcast DMs with the cautious energy of someone approaching a stray animal: Would you be willing to testify at a hearing on a bill that would require third-party oversight when adults set up joint accounts with minors? We’re calling it the Vivian Provision.

I sent a screenshot to Vivian. They’re naming a thing after you, I wrote. Do you want to wear a cape to the hearing or just something with pockets?

She arrived on the day in question in a navy suit with a brooch shaped like a key. “Pockets,” she said and patted one like a magician hiding a rabbit. “Always pockets.”

The hearing room smelled like carpet cleaner and the things people don’t say at Thanksgiving. I told my story the way you learn to when your life has become both cautionary tale and instruction manual: without ornament, with dates and amounts, with the kind of simple sentences that cut.

“The line between care and control is numbers and access,” I said into a microphone that made my voice disembodied and official. “My parents spent four years teaching me that love looked like scarcity. My grandmother spent four minutes reminding me that love looks like receipts.”

Behind me, I could feel Vivian’s presence like a plank under my feet. When the chair recognized her, she read exactly one page: a list of what she had sent and when, notarized, clipped.

“I don’t know how to write a law,” she said, looking up. “I taught high school English forty years. I do know how to grade a paper. If you can’t draw a straight line from the giver to the child, it’s not an A.”

They laughed and then stopped laughing when she went on. “The point of oversight isn’t to punish good parents. It’s to protect children from bad ones. Penalties are not handcuffs so much as guardrails.”

The bill passed committee easily, then the House, then the Senate with a handful of amendments that made the lawyers preen. The governor signed it with a pen she gave Vivian to keep. We celebrated with pie. We do most things with pie.

On the way home from the capitol, my phone vibrated with a number I didn’t recognize. I let it go to voicemail. At a red light, I pressed play.

“Kala.” My father’s voice, baritone rasp shaved down by cheap institutional coffee. “Your mother brought me a book. Not yours,” he said, and I could hear the half-joke he wanted to make dying on his tongue. “The workbook they give us here. It asks questions I don’t like. I keep writing your name in the margins. Didn’t you once say in a speech that we mistake control for competence? I… anyway. I’m not calling to… I’m calling to say I have finally found the bottom of the story. It looks like a well. I am at the bottom. I can see the circle of light. This is not a request. I don’t get to request things anymore. I just wanted to put a marker down, I guess. In case one day you want to know whether I ever said anything true out loud.”

I kept the voicemail. I did not reply. When Amy asked me later what I wanted to do with it, I told her I was putting it on a shelf. Some things you pack in bubble wrap and put away without a date to open.

By spring, Quiet Funds had three chapters and a spreadsheet that made me proud enough to consider buying a laminator. We had facilitators who knew how to sit in a church basement with stale donuts and say to a sobbing nineteen-year-old, “This is not your fault,” and mean it. We had a pro bono lawyer who could file an injunction in his sleep and then eat two maple bars in the parking lot without shame. We had a school counselor who taught us how to spot the kids who made jokes about “earning rent” and never had field trip forms signed.

We also had a waitlist.

“Tell me something beautiful,” Vivian said one night when I called with donor anxiety and the feeling that I was running a middle-school dance alone with a flashlight and hope.

“I taught a girl named Lily how to set up a direct deposit to a bank her mother doesn’t know exists,” I said. “She texted me a photo of the debit card and wrote, ‘It feels like my own lungs.’”

“Beautiful,” Vivian said, voice softer. “I’ll send a check to make sure those lungs keep breathing.”

In late May, Marin got married in the park by the river under a tree that had held teenagers up to kiss longer than we’d been alive. She wore a dress with pockets. Her vows were three sentences. “I do not want to disappear in you. I do not want you to disappear in me. Let’s walk beside each other even when we’d rather be carried.”

Vivian cried. I did too. Julian dabbed his eyes with a napkin that said Pick a seat, not a side. My mother did not come. She sent a gift—cashier’s check made out to Marin & Ezra with a note: I am learning to give without commentary. Marin texted me a photo, captioned: Your mother cheated with neatness. I’m depositing anyway.

After the recession of confetti and the collapse of the folding chairs, Marin and I sat on the curb with our shoes off and our dresses bunched around our thighs.

“You look happy,” she said. “Like a room without wires.”

“I am,” I said, and then, because honesty was a habit now, “I miss what I never had sometimes.”

Marin leaned her head against my shoulder. “That’s grief, not longing. Grief is allowed.”

The parole hearing crept up on me like a bill with your name wrong but your address correct. I had avoided the calendar. Then one Tuesday Amy said, “Do you want to write a victim impact statement?” and my mouth, traitor to my avoidance, said, “Yes.”

In the bare room with the bad lighting, I read a page and a half printed in twelve-point because the review board was rumored to prefer readability. I did not audition for pity. I did not wallpaper over severity. I wrote this:

My father is a man who taught me that scarcity is love. He is a man who taught me that my needs were billable. He is, now, a man in a system that will punish him with the thing he used best—lack.

Parole does not return checks to accounts. It does not unspool years of small humiliations with a flourish. It is, at best, an administrative decision with human consequence. I am not here to ask you to make him suffer or save him. I am here to put a note in the file: there is a daughter who will not hold the door either way.

They granted it. He was released that fall to a halfway house two counties away. The paper ran a paragraph. I put the paper in my filing cabinet. I did not call my mother. I did not change my locks. I did not change my route home. I did not owe myself fear.

On our podcast’s one-year anniversary, we did a live show in the basement of the college library because the auditorium was booked for a jazz trio and a poetry slam had dibs on the union. Forty-seven people showed up: a bank teller who had started refusing to set up minors on joint accounts without a third signatory present, a hairdresser who had stopped “holding tips for my boyfriend,” a kid in a hoodie who hovered at the back until the stickers came out and then put three on his skateboard.

We taped a papel banner to the cinderblock wall that said QUIET FUNDS, LOUD LIVES. Vivian introduced us. She spoke for a minute and thirty-eight seconds about how violets propagate—how you pinch a leaf and press it into damp soil and wait for the small miracle of roots—and then she sat down with her pocketbook like a lady who would fight you with her gloves on.

After the Q&A, a teenage boy with the kind of shoulders that make you think of carrying things approached with a girl at his elbow. “Your thing,” he said, gesturing at the mic, at the audience, at us, “it makes the noise in my head make sense.” The girl nodded. “We thought we were the only broken ones.” I wanted to hug them. I asked if they liked donuts. We all ate donuts.

When the room emptied, a woman hung back, pressing thumbprint-sized grief into the palm of her hand like she could keep it from skittering across the floor.

“I brought you something,” she said, opening a tote bag and pulling out a journal with a plastic cover. “My daughter died ten years ago. I kept at her to be practical. I told her not to be dramatic. I did not see. I should have seen. Your show—” She stopped. Her throat worked. “I listen now. It doesn’t matter to her, but it matters to every girl I meet at the grocery store who apologizes for buying berries. Please give this to someone who needs a notebook.”

I put it on the table next to the stickers. It was gone before we packed up.

Summer came in green and loud. Vivian hosted a small garden party. Not a gala. Not a fundraiser. A handful of women gathered around the long table under the maple. Amy in linen, Marin with grass stains on her calves, Miss Reynolds with her hair loose for the first time I’d ever seen. Julian grilled vegetables like a man who took the phrase don’t burn the zucchini as a personal challenge.

We were on our second pitcher of lemonade when the gate latch clicked and my mother stepped into the yard. She had called the week before and asked—not demanded, not assumed—if she could come to a Quiet Funds meeting. Not as a performer. As a chair.

She paused at the threshold, hand on the latch, eyes wide like an animal who has learned fences can be mercy. Vivian said nothing. She did not get up. She did not put her hand to her chest. She continued slicing lemons, efficient, present. I stood. It felt like a reflex I had trained out and still could not help.

“I brought a pie,” my mother said, holding out a paper box tied with a blue string.

“Store-bought,” Vivian observed, and if a stranger had been present, they would have heard only the observation. Those of us who knew her heard also the sentence beneath: You did not try to out-bake us to be loved.

“It’s from the place downtown you like,” my mother said. Then, because she was herself, she added too quickly, “I asked the clerk which kind people usually take to parties.”

“And what did she say?” Vivian asked, tilting her head.

“That the kind people bring doesn’t matter,” my mother said softly, eyes lowering. “What matters is that they stay and wash the plates.”

There are lines that are apology adjacent. There are also lines that are practice in the mouth. I could not tell which this was or if it had to be either. I stood still. The yard held its breath. Miss Reynolds reached for a lemon and sliced it cleanly.

“Come sit,” I said. It was a choice that had nothing to do with the past and everything to do with what I could bear in the present.

She did. She did not perform penance. She did not cry. She did not try to make Vivian put down the knife and clap. She ate a small piece of pie and did not insist it was the best she had ever had. When Amy asked if she wanted to say anything at the end of the meeting, she said, “No. I will listen.”

I watched her listening the way you watch a hand that has often flinched near your face: with alertness, with skepticism, with muscles ready to duck. When someone said, “My mother told me I spent like a whore because I bought a lipstick,” my mother pressed her lips together. When someone else said, “My father said I was ungrateful for not wanting the joint account when it meant he saw my lunch purchases,” she blinked hard.

On her way out, she put the pie tin in the recycle bin and wiped her fingerprints off the counter with a damp sponge. “Thank you,” she said, looking at me without trying to make me look away.

“Thank you,” I said back, and meant it in the narrow sense the moment warranted. It was neither absolution nor a promise. It was a greeting in a language we might be learning.

The night before the second anniversary of that dinner, Vivian called with the fizz of gossip in her voice. “You haven’t looked at your email, have you?”

“I was being disciplined and not refreshing my inbox during dinner.”

“Open it,” she said. “The country club board wants to give Quiet Funds a community award. At a luncheon. With linen tablecloths. Will you wear pearls? I think you should wear pearls.”

“They asked us to come to them,” I said, awed, not because the club mattered but because the axis had shifted and we were the gravity now.

We accepted. We smiled into microphones and said “thank you” to women who had once nodded away their friends’ discomfort and now carried resource lists in their purses. We didn’t mention the old banner. That would have been an indulgence. Instead we talked about roots and receipts, about oversight and options. Vivian got the line of the day: “If you can monogram a towel, you can put your grandchild’s name on a separate account.”

Afterwards, in the parking lot that had once felt like a stage set I couldn’t stand on without a costume, I leaned into Vivian’s side and watched the wind lift the maples. “You know,” I said, “for a long time I thought laughing at that table would be revenge.”

“And now?” she asked.

“And now it’s just… breathing with a noise.”

She laughed—shockingly loud, scandalizing birds—and looped her arm through mine. “Come on,” she said. “Let’s go home. We’ve got pie.”

On the day the law that bore her name went into effect, Vivian invited the board of Quiet Funds, Miss Reynolds, Julian, Marin, Amy, and Lily to her house for tea. She dressed up like she was going to court in 1958 and arranged violets in a vase that had been her mother’s. She set out the silver spoons that only come out when something is ending or beginning.

When everyone had a cup and a cookie and a sense that something ceremonial was about to happen, I stood and tapped my spoon against my cup the way people do in the movies when they decide to be brave in public.

“A year ago,” I said, “I thought the most I would get from telling the truth was a repayment plan and a permanent bruise. Instead I got money and a map. Instead I got a law named after a woman who kept receipts and did not lower her gaze. Instead I got this room. Thank you.”

Vivian put a hand on my forearm. “To Kala,” she said. “Who taught me that the loudest thing a woman can do is stop apologizing for being alive.”

“Grandma,” I said, eyes stinging, “there are children present.” Lily rolled her eyes in the exact way sixteen-year-olds do when love threatens to embarrass them.

After the cookies were gone and the tea had cooled and people had begun the Minnesota Goodbye in slow concentric circles, the front gate latch clicked. My mother stood there in a coat too thin for the day.

“May I come in?” she asked, not performing the question, making it.

Vivian looked to me. I looked to my bones. “For tea,” I said. “For an hour.” I did not say for always. Boundaries are measured in minutes sometimes, not miles.

She came in. She poured. She did not take the biggest slice. When someone asked her about the bill at the statehouse, she said only, “It’s a good law,” and then she refilled someone else’s cup.

When she left, she squeezed my hand—brief, not clutching. “Happy anniversary,” she said without looking at the calendar. I knew which she meant: the day I learned to ask what money? out loud.

After she was gone, Vivian and I stood in the doorway a moment longer than necessary. The violets on the table were beginning to lean. I adjusted the nearest stem and watched it nod back at me.

“You see?” Vivian said softly. “Even flowers train toward light.”

I thought of the girl with no coat. The college student with two jobs. The woman in the courthouse who did not ask for mercy and got justice anyway. I thought of the grandmother who taught me to keep receipts. I thought of a room full of people who would now gather in church basements and bank offices and living rooms with pie to say, “No,” and mean “Yes” to themselves.

“Let’s call this what it is,” I said, closing the door gently. “Not revenge. Not even redemption. Just breath, finally, in the room we made.”

We turned the sign on the front gate that Vivian had commissioned from the kid down the block who welded things he didn’t know were art. Quiet Funds. Loud Lives. The letters caught the late sun and threw it back onto the walk in little ribbons of gold. We laughed because there was nothing else left to do but live loudly.

END!

News

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside. ch2

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside Part…

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… ch2

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… Part One…

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… ch2

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… Part One…

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… ch2

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… Part One…

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back. ch2

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back Part One The morning sunlight poured through…

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door. ch2

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load