My husband handed me a cup of coffee with a strange smell. “Made you something special, babe,” he said with a grin. I smiled and replied, “How thoughtful,” then quietly swapped mugs with my sister-in-law, the one who always bullied me.

Part One

The velvet napkins were folded into crisp triangles at the Nashville dining table, the silverware aligned at neat, military angles that looked like they’d march off if you sneezed. Nenah always set a picture-perfect table. She learned early that if things looked right, people were slower to question whether they were right. I used to envy that composure; now I recognized it for what it was—a magician’s misdirection.

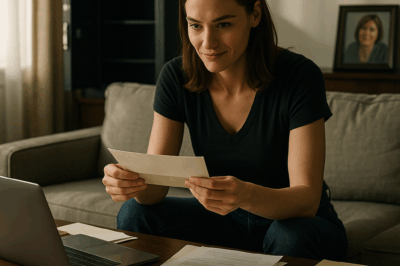

“What’s this?” I asked lightly, when James appeared behind my shoulder with a steaming mug, the ceramic warm against my palm.

“A surprise,” he said, dimples making an appearance like they always did when a camera was around. “Made you something special, babe.”

I brought the cup toward my face and paused. It wasn’t the earthy caramel of our usual Guatemalan roast. Something metallic threaded the steam, thin and sharp as a paper cut. For a second, I was back in our kitchen two months earlier, doubled over after breakfast at his sister’s, listening to James tell the urgent care doctor I must have taken an expired supplement. The doctor was kind. She ordered fluids and tests that found nothing conclusive. We went home with a bill and a chalky anti-nausea prescription.

Across the table, my sister-in-law twirled her spoon in her mug without drinking. “James has been practicing different brewing methods just for you,” she said. Her smile did a thing at the corner like it wanted to be kind but remembered it had a different job.

I’m Christina, twenty-nine, too young to feel this old. When I married James three years ago, I would have bet my life on the fact that the worst thing he’d ever hand me in a mug was lukewarm hot chocolate. Then came the “food poisoning” at his sister’s Christmas party—me in the guest bathroom shaking and sweating, James apologizing for undercooked poultry while Nenah pressed a cool washcloth to my neck and whispered, “Poor thing. Such a delicate system,” like a compliment sharpened to a needle.

I lifted the mug to my lips and put my smile on like armor. “So thoughtful,” I said. “I should…take this call first.”

“What call?” James’s smile faltered a fraction, the smallest crack in porcelain.

I tapped my phone screen—my lock screen, then nothing—and rose. On the way around the table, I let my foot catch on the chair leg and pitched forward, just enough to jolt the table without toppling it, and my hand darted, swift as any conjurer’s. My mug for hers. A switch so simple, so audacious, it felt like stepping off a cliff and finding a staircase where air should be.

“So sorry,” I gasped, righting myself with the napkin I’d displaced. “Clumsy hands.” I didn’t look at her. If I did, I would either flinch or smile too wide, and both would give me away.

In the shadow of the study doorway, my breath stowed high in my ribs, I watched. James and Nenah glanced at each other, a twitch of static across a telegraph wire. She lifted my mug—now hers—and took a sip, eager to sell the show.

Nothing happened. The clock ticked. My heart didn’t. She swallowed again. My pulse returned with a rush that made the room tilt.

“What’s that flavor?” she asked finally, a brightness in her tone that didn’t reach her eyes.

“An Ethiopian blend,” James said. His smile returned in a rush, relief rolling over his features like a wave smoothing the footprint of a lie. “With a touch of chicory.”

I stayed hidden a moment longer. When it happened, it happened fast. A tremor stitched through her wrist. The spoon clinked against china, a hollow sound like the inside of a seashell. She set the cup down too carefully. Color bled from her face.

“James,” she said quietly, then louder. “James.”

He was on his feet, chair legs scraping the hardwood, a sound that made my molars ache. “What’s wrong?”

She gripped the edge of the table. Fingernails—flawless, despite her insistence on “natural”—went white. “It feels…wrong. Everything feels wrong.”

I stepped into the doorway, my thumb steady on the Record button I’d pressed out of habit. I’ve been a planner my whole life. I plan menus and vacations and library holds. It turned out I also knew how to plan for a moment in which the world turned inside out.

James reached for her. “You drank the wrong—”

“Cup?” I said, my voice level and terrible. “Is that the word you were looking for?”

She didn’t look at me. She looked at him, and in that split-second I saw something I had never seen in her expression—abject fear. “Call an ambulance,” she gasped, sliding from the chair to the floor like a puppet with snipped strings. “Please—oh God—James, call.”

I was already dialing. “One five four two Maple Grove Drive,” I told the dispatcher. “Adult female. Conscious, shaking, severe tremors after ingesting a liquid. Unknown toxin.” I made my voice clinical and trustworthy. Nurses appreciate the ones who give details; I learned that in all the time I spent under fluorescent lights.

James knelt by his sister, suddenly small beside the angle of her panic. “You weren’t supposed to drink that,” he whispered. His voice splintered. “You weren’t supposed—”

I held my phone up and, very deliberately, said, “Say that again.”

His head snapped up. For one stupid blessed second, you could see him weighing the cost of repeating the truth and the cost of swallowing it. He chose stupid.

“You weren’t supposed to drink that,” he said again.

The sirens howled close enough to rattle the windows. “Then who was?” I asked, eyes level and open. “Me?”

He didn’t answer, but his face did.

Emergency rooms used to feel like spaceships to me—bright, humming, filled with people who speak a language only they understand. After a year of “accidents,” I knew too much of that language. Hypotension. Elevated liver enzymes. Non-specific distress. Often, a doctor’s eyes slid sideways to James while they hooked me up to monitors. He’s so attentive, those eyes said. He’s so worried.

The attending at Nashville General was not interested in hearsay or pretty eyes. She was interested in the number on the monitor and the stiff, jerking motion of Nenah’s limbs. “Tremors, disorientation, metallic taste,” she said. “And your heart rate—Jesus. Let’s move.”

I didn’t need to see James’s face to know he was cataloging angles. In that kind of crisis, people show you who they are. The helpers help. The sinners calculate. He texted. He paced. He rubbed his thumb against his palm the way he always did when a lie needed polishing.

“How long has she been symptomatic?” Dr. Phillips asked, eyes on the chart.

“Approximately twelve minutes,” I said. “Ingested unknown substance in coffee. Strong metallic odor. Breathing unaffected.”

“And you are?”

“The sister-in-law,” I said. I held her gaze. “And possibly the original target.”

Her attention sharpened like scalpels. “Explain.” I lifted my phone and pressed play. The kitchen. The switch. The tremors. James’s voice. You weren’t supposed to drink that.

She listened without interrupting, pen still, breath steady. When the recording ended, she exhaled through her nose. “We’ll be drawing comprehensive tox screens,” she said. “And calling the police.”

Within an hour, a detective in a jacket the color of good whiskey appeared. She said her name was Mendoza and that she had two kids and that she had seen enough things like this to know to keep her tone gentle and her eyes hard. “Let’s start at the beginning,” she said, and I did. The undercooked chicken that tasted just fine. The tea with a floral smell that made my molars hum. The call from this morning’s study where my breath stayed high and my body went still.

“And you documented?” she asked.

“Yes.” I pulled a small notebook from my bag, dog-eared to the last six months. “Dates. Symptoms. Who prepared the food. Duration.” On a separate page: myology of suspicion. The hours James had spent “running errands” with his sister. The way their voices went flat when I walked into a room. The e-mail opener I’d glimpsed on his laptop—pharmaceutical supplier—before he snapped it closed with enough force to send a shiver through the wood of the table.

She flipped through the pages slowly. “You did good,” she said. “Now we’ll do the rest.”

They brought James in while the tox screen ran. Security didn’t cuff him—he was a husband, not a suspect, not yet—but they stood close enough that the chair legs made a different sound scraping the floor. He had the look of a man trying to peel an orange with his fingers and a closed fist.

“Christina,” he said. “We can talk about this.”

“Here,” I said without moving, “or with her?” I nodded toward Detective Mendoza.

His smile spasmed. He went for charming. It slid off the stainless steel of her expression.

“We were just trying to slow you down,” he said finally, we which made my skin crawl. “You were—working yourself to death. The board meeting next week—you looked exhausted. I made coffee to help you relax, that’s all.”

“That explains the notes you kept,” she said, holding up an evidence bag that a second detective had just handed her. “These were retrieved from your desk at Anderson Marketing, Mr. Bennett. Twelve months of dosage records and reactions. The compounds labeled in clinical shorthand.”

He blinked. I watched the fight go out of him like air leaving a busted tire. “It wasn’t like—” he began, and then stopped, because the truth had caught up and settled on the bed railing, heavy and breathing. “We didn’t think—”

“No,” I said. “You didn’t.”

The tox screen came back a half hour later. Dr. Phillips’s mouth was a line when she stepped into our little circle. “We found elevated levels of several compounds not meant for human consumption outside of clinical testing. One is particularly concerning at high concentrations. Whoever introduced it knew exactly what they were doing.” She glanced through the glass at Nenah, who was now stilled, her body slack and trembling less. “Your sister-in-law is lucky you switched the cups when you did.”

“Lucky,” I repeated, letting the word sit on my tongue like a pill, letting it dissolve into something bitter and useful.

Detective Mendoza turned to James. “Mr. Bennett,” she said, voice softened not at all, “you are under arrest for suspicion of attempted homicide, conspiracy, and procurement of controlled substances. You have the right to remain silent…”

He looked at me, panicked and small, and for a moment I almost felt sorry for the man I had loved. Then I remembered undercooked poultry and floral tea and the way he had watched me shake in a bathroom while he recalibrated a story.

They brought Nenah in a few hours later. She had insisted on answering questions. She had a blanket around her shoulders, the hospital beige that matches no skin tone but insists, anyway, that you belong here now. The bravado was gone; something raw stood in its place.

“It started with a meeting,” she said without prompting, eyes on the table. “Henderson Account. They wanted fresh eyes. Christina had them.” Her mouth twisted. “You did.”

“You could have worked with me,” I said quietly.

“You always say that to people who are drowning,” she snapped, and then her voice softened. “I was drowning. James said he could help. ‘Just a little sick,’ he said. ‘A wake-up call.’ But it didn’t work. Every time you got ill you dragged yourself to the meeting anyway and shone and made jokes so the clients forgot the pauses between sentences.” She took a breath that rattled. “James kept saying, ‘One more time. One more try.’” She looked up at me. “I thought you were perfect.”

“I’m not,” I said. It felt important to say it out loud, like categorizing a specimen correctly in a lab.

A nurse slipped in with a cup of water. “Sip,” she said gently. “Then sign these consent forms.”

“Will this be public?” Nenah asked, voice small.

“Yes,” Detective Mendoza said. “You made it public when you made it criminal.”

Nenah nodded. She drank. Her hands shook. I watched her and felt a thing I hadn’t expected to feel: pity. It is a dangerous thing to pity the person who tried to kill you, but danger and pity are old friends. I looked away.

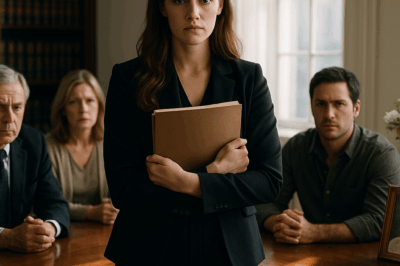

James’s arraignment was the next morning. The hearing room smelled like varnish and processed grief. The judge’s hair was the color of wisdom. She read the charges in a voice that wasn’t mean but held no space for comfort. Defense counsel talked about stress and intention and family obligations. The prosecutor talked about dosage and notes and escalation. The judge talked about bonds and records and a past statement where James had suggested killing mice to “recreate results.”

I sat next to my lawyer and kept my hands folded in my lap where I could see them. My ring, my restored ring, threw a tiny glimmer across the back of my thumb every time I breathed. When the judge denied bail, James’s head dropped. Behind him, his mother made a sound like a kettle left on the stove. Nenah sat two rows back, a clot of nurses between us, colorless and awake.

On the sidewalk afterward, someone from a local station asked me for a statement, and I learned that the thing people say is true: the camera really does flatten you. You have to push your voice through it like blood through a clot.

“My husband and his sister are not monsters,” I said, because it was true and because I wanted someone considering their own kitchen to hear me. “They are people who let ambition and entitlement eat their insides until the only thing they could taste was bitterness. I hope they go to prison. I hope they get help there. I hope anyone who sees themselves in their story stops before it becomes someone else’s story.”

Afterwards, Dr. Phillips found me at the vending machines. “Your potassium’s fine,” she said, dry as paper. When doctors joke with you, it means you belong to their world a little. “One more day of observation, then I expect to see you on a beach somewhere, not in my waiting room.”

“I don’t like the beach,” I said, surprising myself. “Sand in everything.”

“A cabin, then,” she said, smiling. “Somewhere with quiet.”

A week later I drove to the Smokies by myself. A cabin, a fireplace that took work to start and rewarded me with a crackle, a line of pines so straight they made my spine ache to look at them. I brought real coffee, ground the beans with the fury of a woman who has earned her bitterness and chooses sweetness instead. The first mug tasted like a sermon preached by a kind man. I slept for nine hours.

When I came back to Nashville, there was a letter waiting, addressed in unfamiliar handwriting. It was from the Henderson team. “We’d like to offer you the position of Vice President, Client Strategy,” it said. “We’d like you to write the script here.”

I sat at our—my—kitchen table and cried quietly. It wasn’t relief, not exactly. It was whatever happens when someone tells you the story you wrote under duress is still legible in daylight.

Part Two

People Brought Casseroles.

That is one of the weirder things about being a victim of attempted murder committed by your spouse and his sister: you end up on lists you never thought you’d be on. The women from my book club made macaroni and cheese that could heal a nation. My neighbor sent soup in Mason jars with fabric lids that looked like little hats. Someone brought a lasagna that tasted like the memory of a grandmother who had never been mine.

Dad came by with a crockpot and an apology written not in ink but in time: he sat on the couch and watched basketball and didn’t talk about it unless I did. This is what real contrition looks like, it turns out. It looks like silence that isn’t sulking. It looks like asking, “How is your back? I noticed you winced.” It looks like not telling me to forgive before I know what forgiveness would cost.

The trial date bloomed on the court calendar like a bruise. My lawyer, a meticulous woman who wore kittens on her socks, guided me through the pieces. She said we would likely not have to take the stand; the recordings and the notes and the tox screens would do the heavy lifting. “But I want to,” I said, surprising us both.

“Okay,” she said. “Then we’ll make sure your voice knows it’s allowed to be loud.”

On the first day, the prosecutor walked the jury through the months like a map. February—symptoms. April—tea. June—breakfast. September—coffee. He spoke in the precise tone of someone who sets a bone. The defense tried to paint me as stressed, as dramatic, as overworked. “She is extremely competent,” they said, meaning “She is less believable.” My lawyer stood and reminded them that competence and vulnerability are not opposites. You can be the person everyone asks to plan the retreat and still know when something in your coffee is wrong.

When the jury left the room for the last time, the quiet felt like a storm at sea. Then the foreperson came back and the words guilty moved through the courtroom like a kindness. The judge added her own words about premeditation and privilege and punishment. Sentences were spoken. The sound of a gavel hitting wood is theatrical in movies. In real life it sounds like the end of a song you didn’t know had lyrics.

Afterwards, outside, reporters asked me how it felt. I said, “I don’t know yet,” because it was true. Then I went home and slept for an hour and then went into the office, because my team had a presentation to deliver and we had practiced and they deserved a leader who showed up. It was the best work I’d done all year. I realized then that the story of my life had shifted around a new axis. It didn’t revolve around a kitchen table anymore. It revolved around the center of myself.

Success did not feel like triumph. It felt like a full calendar with room to breathe. We built a campaign that made people cry while also buying things, which is the marketer’s white whale. Henderson renewed. We added three more clients from the conference. I stepped into the VP role with the particular terror of a person who has just argued in a court that she is reliable and must prove it in PowerPoint.

I changed my locks. It was symbolic and also sensible. I replaced the mugs James had given me. I kept the kettle; there was nothing wrong with the kettle. I bought coffee beans from the shop where the barista remembers your order but pretends not to so you can practice saying what you want out loud.

What surprised me were the emails that arrived like little birds landing on my windowsill. I saw you on the news and recognized the look on your face. My sister used to “help me with my medication” when she needed me quiet. My husband says he’s just trying to keep me safe but I throw up after soup. I’m a recruiter looking for a strategist with ethics; are you open to chat?

I could not answer all the letters, not in full, but I did answer some, and I wrote, “Trust yourself—your nose, your gut, your pattern-recognition muscle. Keep records. Tell one friend everything. You are not dramatic; you are accurate.” It turns out that being a woman who is “a lot” can save your life.

One afternoon, Dr. Phillips called to ask me to speak at a hospital staff event about patient advocacy. “Most people don’t document like you did,” she said. “If they did, we could catch more ‘accidents.’ We could catch ourselves, too, when we want the easy story.”

I stood in a conference room with bad coffee and good intention and said, “Here is what it looks like when you’re trying to decide if the person in the bed is the unreliable narrator of a story you’ve seen too many times—or someone being written out of their own life. Here is what both look like. Here is how you pause.” A nurse cried. A tech nodded. A doctor who had seen me twice in my worst moments shook my hand and said, “I’m sorry I doubted you.” That mattered. Accountability is a kind of aftercare we don’t always get.

And then—because life contains multitudes—Bruno and I went camping. We brought a tent and a dog-eared map and a ridiculous amount of snacks, and we tried to set up our shelter without yelling at each other like people in a TV show. We failed and then laughed and then succeeded. In the morning, he brewed coffee on a little stove and handed me a mug that smelled like a sermon again, and neither of us flinched.

We make rituals after trauma the way shipbuilders test knots. One of ours is this: when he hands me something to drink, he takes a sip first, not because we suspect but because we have agreed that this small sacrifice of heat from the top of the mug is a way to say, “I know the story we lived. I honor it. I won’t ask you to pretend it didn’t happen.”

Another ritual: on the first Saturday of each month, I text Dr. Phillips a photo of my feet planted on the kitchen floor with the caption, “Alive and hydrating.” She sends back a photo of her lab coat draped over a chair like a ghost with good posture and writes, “Alive and charting.”

Time passed. The narrative softened around the edges. People in my building started greeting me as “Hey, Christina-from-28B” instead of “Is that the woman—?” Dad kept dancing. Mom joined a support group and learned the phrase “adult child,” and then she learned how not to use it as a weapon. She asked me once how she could support me without asking me to do the labor of teaching her how to support me. I said, “You just did,” and we both cried. Crying becomes holy when it is rare and unhurried.

I saw Nenah once, months after her sentencing, at a restorative justice session my lawyer had suggested and my therapist had blessed if and only if I wanted it and had slept well the previous three nights. She wore the same beige of hospital blankets. She looked like a woman who had finally chosen to be heavy somewhere that could bear it.

“I brought you this,” she said, her hands shaking. “It’s for Dr. Phillips.” It was a list of books about ethics and clinical trials and a handwritten note: I’m sorry for the ways I made you doubt your training.

“And this is for you,” she said. She slid a small object across the table wrapped in newspaper. My first thought was No more rings, but when I unwrapped it, my throat closed. It was a keychain—ugly and beautiful—made of hammered brass in the shape of a coffee mug. On it, clumsy letters stamped: I lived.

I didn’t hug her. I didn’t forgive her. I did put the keychain in my palm and close my hand and feel the impression of the letters against my skin. We are not obligated to turn the other cheek when the first one still aches. We are obligated to look in the mirror and name the woman who looks back as someone we will not abandon.

When I got home, Bruno was painting the wall behind our bookshelves a color called “Quiet Pine.” He turned, brush in hand, and saw my face and the mug in my palm.

“That’s ugly,” he said gently.

“I love it,” I said.

A year after the verdict, Henderson hosted a dinner to celebrate their renewal. The room was filled with people who talk about synergy with straight faces and then go home and cry about their kids’ math homework. I gave a keynote about trust and storytelling and the ethics of persuasion. “We sell hope here,” I said. “Let’s not sell it with rot in the beams.”

Afterwards, the COO took my hand and said, “You could have sued them for everything.” I shrugged. “Prison seemed sufficient,” I said. “And I need my hands free to build.”

On the drive home, the skyline looked like someone had drawn it with a soft pencil and then gone over the lines in ink. The radio played a song we’d danced to in the living room when the world was small and scary. Bruno turned the volume up and the windows down and we sang like idiots instead of crying. Both are valid.

Back at our apartment—the basil plant thriving now—we stood in the kitchen, the same old kettle on the stove, the new mugs lined up like soldiers. He scooped beans, ground them, poured water. He handed me a mug and took his ritual sip, and we both grinned because it still mattered and because we were allowed to hold joy in the same hands that had held fear.

“Made you something special,” he said softly, teasing the ghost of the line that started it all. He could say it now without making me flinch. That is a miracle we do not name enough: you can reclaim a sentence from the mouth of a monster and let it live in the mouth of someone who loves you.

“Thoughtful,” I said, and meant it.

When I tell people this story, they want a clean ending. They want me to say my sister-in-law is reformed and my ex-husband found God in a library and my parents reinvented themselves as social workers who speak at conferences about enabling. The truth is messier. James writes to me from prison; sometimes I write back. He says rehab is hard and court-ordered therapy is embarrassing and that he signs up for every class he can because it is a way to count days and stack paper. He says he is sorry. I do not tell him I believe him. I do tell him I believe in people sometimes doing one good thing and then another.

Nenah sends my mother postcards from whatever program she’s in this season. They are mostly blank on the back—images of rivers and wheat fields—and once she wrote, I got an A on soldering. My mother puts them on the refrigerator with magnets shaped like fruit. She is learning to let a small thing be small without needing it to be a miracle.

Dad keeps dancing. He sends me a photo once a month from the community hall: a row of retired men in socks and earnestness, a line of women in polka dots and grit. He says, “We’re learning a new step. You move backward and trust that your partner doesn’t step on you.” I text back, “That’s just called living, Dad,” and he sends fifteen heart emojis because he still hasn’t grasped restraint in digital communication and I pray he never does.

And me—I work. I mentor. I sit with women at coffee shops who are trying to decide if they will walk out the door that will save their lives. I tell them, “It is okay to be loud.” I tell them, “It is okay to be careful.” I tell them, “Here is how you switch the cups without looking.” Sometimes, they laugh through tears and say, “That seems dramatic,” and I say, “Yes. So is being alive.”

I put the brass mug keychain on the hook by the door. It gleams dully in the afternoon light. It reminds me every time I leave and every time I come home that I wrote a story I can live in.

People still bring casseroles sometimes—grief casseroles for other things, other losses that are smaller and therefore easier to carry because we know how. I accept them with thanks and return the dish washed and sometimes with brownies in it, because the best revenge is not kindness; the best revenge is a life so sturdy it can afford kindness where none is owed.

If you need the ending, here it is: there is no more poison in my house. There is no more pretending at my table. There is coffee that tastes like sermons and mornings that taste like quiet. There are people who tried to kill me and now have to live with that attempt written on their bones. There is a woman who believed herself dramatic and discovered she was simply accurate.

There is a man who says, “Made you something special,” and is right.

There is a woman who answers, “How thoughtful,” and is, too.

END!

News

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside. ch2

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside Part…

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… ch2

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… Part One…

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… ch2

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… Part One…

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… ch2

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… Part One…

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back. ch2

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back Part One The morning sunlight poured through…

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door. ch2

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load