The Call and the Bruise

The nurse’s voice was too steady. That’s how I knew something was wrong. People think panic announces itself with screaming. It doesn’t. Panic dresses up as calm and speaks in short sentences.

“Mr. Harper? This is Nurse Klein from Westview Elementary,” she said, each syllable clipped like she’d ironed it. “Your son needs you now.”

The last word caught. Not soon. Now. I didn’t bother to ask questions. I’m not sure I even said goodbye. I was already moving—keys, wallet, phone—my body ahead of my mind. Outside, the late-October sky wore a hard blue. The air had that thin, metallic bite that tells you winter is rehearsing in the wings.

I drove like a man chasing a ghost. Red lights were suggestions; speed limits were trivia. The hummingbird panic that lives under the sternum fluttered hard, but another voice rose to meet it. The voice the Corps had given me years ago—calm, methodical, impolite to chaos.

Breathe. Observe. Decide. Move.

When I reached the school, everything slowed. It always does just before impact. Westview looks like every elementary school in America—the brick front, the flag at half-mast for something the kids don’t quite understand, the hand-painted mural near the entrance that says BE KIND in colors bright enough to shame you for failing.

Inside, the office hummed with printer heat and fluorescent light. The secretary looked up. I didn’t need to give my name. She’d already buzzed me in, hair tucked behind her ear like a question mark.

“He’s with Nurse Klein,” she said, softer now. “Second door on the right.”

I opened the door and saw him—small frame shaking on the vinyl cot, one eye already swelling purple. He had the look of a boy trying to be a man in a world that doesn’t give extra credit for effort.

“Hey, champ,” I said, and I made my voice level. If there is one useful lie parents learn, it’s how to sound like nothing is wrong when everything is. I knelt, knees cracking, and brushed hair from his forehead. “What happened?”

His lips trembled, the way a dock does when a boat bumps it. Then words came in jagged pieces.

“Dad, I… I went home for lunch. Mom was with Uncle Steve. I tried to leave. He slammed my face into the door, locked me in my room. I jumped from the window. They’re still there.”

The room contracted. The air thickened until breathing felt like a job. My pulse slowed instead of quickening. People think military training makes you fearless. It doesn’t. It makes you deliberate. It stacks instinct on top of discipline and sands the panic off the edges.

He touched my son.

That was his first mistake.

The second was assuming I was still the man I pretended to be at home. The one who says “It’s probably nothing” and “I’m sure there’s an explanation” because explanations are easier than confrontations. I carried my boy to the car, every muscle coiled and humming, like a bridge under load.

In the passenger seat, he curled in on himself, backpack clutched to his chest like a shield. The bruise under his eye was blooming by the minute, the sickly spread of purple and yellow like an oil spill on skin. He kept one hand in his hoodie pocket. When I eased the zipper down to check for other injuries, I saw the small Swiss Army knife I’d given him on his tenth birthday. He’d never carried it to school before. He’d carried it today.

“You did good,” I said, buckling him in. “You did exactly what you needed to do to get safe.”

He nodded, a tiny motion, relief and shame wrestling behind his eyes like boys on a playground. He is eleven. He still thinks a father can fix anything with a firm voice and a wrench. I hate how hard the world works to correct that notion.

“Hospital,” I said to the emptiness between us, more to myself than to him. “We’re going to get you checked and documented.”

He flinched at the word documented—a grown-up term that doesn’t belong in the mouth of a child. I put a hand on his shoulder. “Documentation is just proof,” I said. “Proof keeps liars small.”

On the drive to urgent care, I called the school back, let them know he was with me, told them to note the time. Then I called the non-emergency line and reported what my son had said, carefully, precisely, the way you narrate coordinates. The dispatcher’s voice had that same trained calm. “We’ll log it,” she said. “An officer can meet you at the clinic if you’d like.”

“I’d like,” I said. Want is a hobby. Like is a plan.

At the clinic, a nurse named Tasha with kind eyes and tattooed constellations on her wrist took us straight back. She spoke to my son, not to me, which I admired. “Can you tell me on a scale of one to ten how much it hurts?” she asked, kneeling.

“Depends if I touch it,” he muttered, attempting humor he hadn’t earned and therefore had. “Like a seven. Or a sixteen.”

“That’s a lot,” she said. “We’ll be gentle.” She glanced up at me, a quiet question: Do you need a minute? I shook my head. Not yet.

The physician’s assistant examined him, documented the swelling, photographed the bruise with a clinic camera and then again with my phone at her suggestion—“for your records,” she said, and I could have kissed her for turning care into evidence. She checked for concussion, for fractures, for injuries that hide like cowards.

“Looks like soft tissue damage,” she said finally. “No fracture. We want to keep an eye on it. Ice fifteen minutes on, fifteen off. Ibuprofen as directed. If he vomits or seems disoriented, bring him back.”

The officer who arrived had forearms like fence posts and a wedding band that looked new. He took my son’s statement gently, wrote in a notebook with a pen that didn’t squeak. When he was done, he closed it with a soft finality.

“We’ll open an investigation,” he said. “Given the allegation and the relationship, the case will also get flagged for CPS review. Do you have a safe place to stay tonight?”

“Yes,” I said. “With me.”

“Okay. Keep him with you. If you go back to the house, don’t go alone.”

I thanked him and meant it. Then I took my son home—not home; to my townhouse. The word home had become a map with a hole burned in it. He fell asleep on the couch with an ice pack and a bowl of Goldfish crackers within reach, the TV murmuring some gravel-voiced cartoon he liked. I stood at the window and watched the late-afternoon light shoulder its way down the street.

My wife—Mara—had told me Steve was just helping while I traveled for work. “Your brother’s around,” she’d said lightly. “He can pick up groceries, fix the faucet.” Steve is the kind of charming that turns sour in the sun. He won prom king in a suit he never returned and spent the summer after high school on couches that weren’t his. He calls it charisma. I call it gravity—he bends boundaries toward himself.

I let myself believe her because believing is easier than digging. You don’t have to scrub your knuckles raw if you never lift the tile. But the bruise under my son’s eye was not imagination. The tremor in his voice was not invention. The pieces aligned with every memory I’d buried: the laughter I overheard when I came home early and the way it snapped off when the door opened; the locked phone she angled away from me, screen turning black like a summons; the smell of cologne that wasn’t mine lingering on a towel I hadn’t used.

It wasn’t just infidelity. It was invasion. My own blood sleeping in my bed, touching what wasn’t his. And now, hurting my son. Betrayal had stopped being abstract. It had a face. Two faces. Both staring back at me from the cage of my past.

I kept my calm. Outwardly, I was only a father tending to his child. Inwardly, I was cataloging every move.

When he woke, I fed him pasta with butter and a mountain of parmesan, the only meal I know how to cook that is both comforting and edible. He ate with the slow focus of a soldier rebuilding a campfire. After, I tucked him into my bed and took the couch. He fell asleep holding the Swiss Army knife like a talisman. I watched the ceiling fan for a long time and didn’t sleep at all.

At three in the morning, I sat at the kitchen table with the laptop open and the kind of coffee you make when you don’t plan to be human tomorrow. The house was as quiet as a lie. I started with phone records. Numbers labeled work called late, long durations, each one a needle in a fabric I had been pretending not to notice unraveling. Then the bank statements—hotel rooms booked under her name, but two breakfasts charged; gas stations far outside her commute; EZ-Pass pings on weekends she said she’d spent at the park.

Every fact confirmed what I already knew. Their affair wasn’t a mistake. It was a life built in shadows. And it had spilled into my son’s daylight.

I moved like a ghost through my own house the next morning after drop-off, while he sat in class with a note excusing his absence the day before and the nurse no doubt checking on him with the kind of vigilance adults cultivate when a child’s story doesn’t fit on a single line. Drawers I had never opened because trust had trained me not to began to give up their secrets—receipts folded small, a photograph snapped with a bad angle and worse judgment, lipstick on a shirt that wasn’t mine. On the kitchen counter, the blue bowl we kept for keys held a hotel key card; under the sink, a shoebox with a few letters, their edges soft with handling. My hands were steady. Steadier than I expected.

I opened her laptop when she forgot to close it on her way to “yoga.” She had a folder named TAXES. Inside was a folder named 2019. Inside that, another named RECEIPTS. Inside, because shame does not have imagination, a subfolder named TRIP. In TRIP, photographs. Knees tangled in my sheets. Shadows that were not mine on the wall by my dresser. My son’s toy truck on the carpet’s edge, green plastic bright and obscene. They hadn’t just betrayed me. They had polluted the one place meant to be safe.

I said nothing. Not yet. Silence is a tactic. Silence gives you the upper hand. Silence makes them believe you’re blind. Meanwhile, you load the rifle called truth.

I bought cameras. Small, discreet devices with lenses like guilty eyes. One for the kitchen, tucked between the recipe books Mara never touched. One for the hallway, its black eye peeking from beneath the shelf where we kept board games we pretended to enjoy together. One facing the back door, because that’s where people enter when they don’t want to be seen. I ran the wires clean and hid the one blinking LED with a piece of electrical tape. I set the feeds to back up to a cloud account with a name that would bore a hacker to tears. I learned the rhythm of the house through my phone—when the sun slanted across the tile, when the mail came, when the ice maker croaked like a heron.

And then, two days later, while I sat in my office pretending to reconcile a quarterly report that did not matter, my phone buzzed. Motion detected. I opened the app. The hallway woke to motion, grain swimming into clarity like a photograph developing in a bath.

Steve walked through my door like he owned it. My wife—Mara—met him in the kitchen with a kiss that belonged to me once and no longer did. They laughed, careless, like actors caught between takes. Then the sound that froze me.

My son’s voice, small, scared, from offscreen. “Can I go back to school?”

“Later,” Steve snapped. The camera in the hallway caught him moving toward the sound. The thud as a door hit the frame hard enough to make a picture rattle. A muffled cry.

I watched the footage alone in my office, the door locked, the blinds slanted closed. Time slowed to syrup. I kept my posture relaxed, hands loose on the mouse, because even rage has to know how to breathe if it wants to do a job right. I burned the images into my mind. Then I copied them onto a single drive the size of a dog tag and slid it into my pocket next to a coin I’d carried since Fallujah.

That evening, I cooked. Memory food. Mom’s chili, the one I’ve made so many times the recipe card is translucent with oil and grief. I set the table like a magazine ad. Cloth napkins, wineglasses, the good plates Mara has always said were “for when it matters.” It mattered.

She came home later than usual, cheeks flushed, eyes too bright. She kissed my cheek like she was relieving me of something instead of offering it. “You made chili,” she said, surprised, a little wary. “What’s the occasion?”

“Family dinner,” I said. “We haven’t had one in a while.”

The boy ate quietly, protective as a wolf with a broken paw. I watched him watch her and wondered when exactly he had learned to tell the difference between a smile and a baring of teeth. After he asked to be excused, I sent him to my room with his math homework and left the door cracked so he could hear the ocean if one started in our kitchen.

The drive sat on the dinner table like a tiny, polite grenade. She noticed it while she served seconds and froze when she saw my face. We have ways of reading each other, even when we’ve misread everything else.

“What’s that?” she asked, going for lightness and finding tin.

“Press play,” I said.

She did. The footage filled the laptop screen. Her expression collapsed in stages. Denial first—that’s not what it looks like—then panic—this can be explained—then the desperate, wild realization that there was no exit.

“Please,” she started, and I held up my hand, calm, controlled, deadly quiet.

“You let him touch my son.”

Tears came fast because she knows how to summon them. Excuses tumbled because she knows that sometimes the most unbelievable thing is the truth. She tried to close the laptop, but the footage kept running, indifferent to her shame. Every second cut deeper than any words I could say.

“I made a mistake,” she said.

“No,” I said. “You made choices.”

Her sobs grew louder, messy. She begged, promised, swore it would end. “It didn’t mean anything,” she said, which has to be the laziest lie humans ever invented.

“Then why did you lock my child in his room?” I asked. My voice didn’t rise. It went down—quieter, colder. “Why did you let a man put his hands on him?”

She didn’t answer, because there isn’t an answer that matters.

I leaned forward, the discipline finally stepping out from behind the curtain where it had been waiting. “Here’s what will happen. You will leave this house tonight. You will not return. You will not contact our son except through me. If you try to see him at school or at practice, I will file for a protective order and I will win. When the courts see this footage, they’ll understand why.”

Her breath hitched. You can tell when realization lands. The affair wasn’t her undoing. The violence against our son was. That was the rope tightening around her neck.

I slid the drive back into my pocket. My decision was final, and she could hear the click of the bolt even if she couldn’t see the door.

“Steve can have you,” I said, standing. “But he can’t save you.”

She left that night with a duffel bag and a face crumpled by consequence. I packed a backpack for my son with clothes for a week and drove him back to the townhouse. He slept in my arms, his bruised face pressed against my chest, the rhythm of his breath coaching mine toward something like sleep.

He would heal. He is stronger than both of them combined.

As for me, I felt no pity, no rage. Only clarity, clean as a winter sky. They thought betrayal made me weak. They forgot what I was trained to do.

Assess. Endure. Execute.

I didn’t need blood. I didn’t need violence. I needed the truth. And the truth destroys people more completely than vengeance ever could. He touched my son once. That was enough to end them both.

The Ghost in the Walls

The first night after she left, the house made more noise than usual. Settling sounds, the kind that live in drywall and ductwork—pops and sighs, a distant water hammer somewhere like the bones of a whale remembering the ocean. Old noises, new meaning. The refrigerator’s compressor kicked on and my shoulders went up like it had a knife. Training wears off slowly. Betrayal lingers like smoke.

My son slept in my bed because monsters don’t live in rooms with dads in them. He had an ice pack on his face and a dog-eared paperback on his chest and slept the way kids do after a day that should have broken them—mouth open, hand fisted, innocence duct-taped together with exhaustion. I sat in the hall with the door cracked and watched the sliver of his face in the light from the bathroom. The cut under his eye had become a scab, a thin punctuation mark the day insisted on keeping.

At 2:00 a.m., the townhouse’s HVAC sighed like a weary animal and I finally lay down on the floor, the carpet twenty years old and prickly, and let my back find its own gravity. You can sleep anywhere if you’ve slept everywhere. When I woke, it was because my son had rolled over and murmur-asked, “We’re safe, right?”

“Yeah,” I said. “We’re safe.”

In the morning, the action items assembled themselves like a briefing. Call the detective. File for an emergency protective order. CPS will want to see him. Tell the school the new pick-up list: me, and only me. Change the locks at the house. Pull the camera feeds and make redundant copies. Schedule a pediatrician follow-up. Find a therapist who speaks Children and also speaks What Happens When People Who’re Supposed to Love You Choose Themselves.

Make coffee. Extra.

He poked at a bowl of cereal like it had done something to him personally. “Do I have to go to school?”

“Not today,” I said. “Today we handle the grown-up parts. Tomorrow, we get back to routine.” He nodded, relieved and reluctant all at once. Routine is how kids craft meaning. Routine and chicken nuggets.

Detective Alvarez called me back before nine. His voice had that steady, slightly gravelly quality that says he’s seen enough not to flinch but not so much that he’s numb. “We’ve got your clinic photos,” he said. “And the nurse’s notes. You emailed the video?”

“I uploaded a secure link and a physical drive,” I said. Belt and suspenders; I don’t care if the pants are too tight. “There’s also corroborating data—phone records, credit card statements. I started a timeline. Timestamps match the footage.”

A pause that could have been appreciation. “You’ve done my job for me.”

“I don’t want your job,” I said. “I want a different past.”

“Understood,” he said. “We’ll want your son to give a recorded statement in a child-friendly suite. CPS will coordinate. I can meet you at the courthouse if you’re filing for a temporary order.”

“See you there,” I said.

The courthouse is what happens when tired becomes architecture. A lot of brown. A lot of signs laminated against hope. The clerk behind the glass had the demeanor of someone who runs marathons for fun and chooses kale on purpose. She slid forms through the slot with the gentleness of a librarian and said, “There’s a domestic violence advocate upstairs who can help you fill these out. The judge reviews ex parte petitions at eleven.”

The advocate was named Rene. She wore flats and a cardigan that looked like it had hugged a lot of people. She did not ask me to rehearse the whole story; she asked me to circle facts, not summaries. “You can add narrative later,” she said. “For now, we want the scaffolding. Undersign where it says ‘petitioner.’ Check the box for immediate danger.”

“Will they notify her?”

“Yes,” she said. “But you’ll have a temporary order before they do, if the judge signs. And a hearing date for a full order within two weeks.” She glanced up at me, eyes kind and cutting at the same time. “You’re doing the right thing.”

“That’s new for me,” I said. “Lately, I feel like I’ve been doing the last thing.”

“Sometimes those are the same,” she said. “Right feels like last when you waited too long.”

The judge signed with a pen the size of consequence. A bailiff walked me through the terms: no contact with me or my son; no entry to the house; supervised visitation to be determined; return of personal items coordinated through law enforcement; firearms relinquishment. He read each line like a vow. I initialed like a soldier.

Outside, the sky had the brittle brightness of early winter. My son tugged my sleeve. “Can we get tacos?” he asked. The question was ordinary and holy. “Yes,” I said. “Extra guac. We’re celebrating paperwork.”

At the taco place, he ate with both hands, sauce on his mouth like war paint. The world continued to spin, which felt rude. My phone vibrated until the table hummed—the group text with my sister, with my friend from the service, with a neighbor who’d always liked us better than she liked Mara but never said so out loud until now.

Then the unknown numbers started. I flipped the screen over. “If it’s important, they’ll leave a message,” I told myself, and chewed slower. When I finally checked, there were three voicemails, all short, all her, all different flavors of the same plea.

The first: “We need to talk. You can’t just—this isn’t fair.” The second: tight, clipped. “My lawyer will be in touch.” The third, hours later: watery. “Please. I made a mistake. I’m so sorry. Let me explain.”

I set the phone down. Let me explain is a synonym for Let me edit. I did not call her back.

At two, a CPS caseworker named Nadia arrived at my townhouse with a tote bag and a voice that had patience baked into it. She introduced herself to my son first, knelt so her eyes were level with his. “I’m here to make sure you’re safe,” she said. “And to help your dad make a plan to keep you that way.” He looked at me and I nodded. He told his story in a voice that grew steadier as it moved. Nadia didn’t interrupt. She didn’t correct his chronology when it wandered. She just wrote and nodded and let him finish.

When it was my turn, I kept the sentences short, like shooting at a target and hitting one round per breath. “I have cameras. This is the time stamp. Here’s the clinic documentation. This is the officer’s card. These are screenshots of hotel charges and gas receipts. And these are texts from Steve, some of which I think he meant to send to her but didn’t.” I slid a printed thread across the table. Nadia’s eyebrow went up at a message that read, Make sure the kid stays upstairs next time.

“You did all this in twenty-four hours?” she asked.

“I’ve had twelve months to notice and one day to stop pretending.”

She nodded, tucked her hair behind an ear with a practiced gesture. “We’ll recommend emergency placement with you. That can be formalized in family court this week. Supervised visits for mom, if the court approves, at a center. No contact with the brother pending the criminal case. We’ll also connect your son with a trauma-informed therapist. Does he have preferences? Male or female?”

“Whoever’s good,” I said. My son said, “Not a jerk,” and Nadia smiled, small and genuine. “We try to avoid those.”

After she left, I sat on the floor and changed the password on every account I could name. Bank logins, email, school portal, even the streaming service. It felt petty and also necessary. I added multi-factor to accounts that didn’t have it and revoked shared access on the thermostat because pettiness and necessity sometimes share a fence.

I called the school and asked for a meeting. The principal, a balding man with a kind mouth and the permanent fatigue that accompanies carpool duty, ushered us into his office. He had already been briefed. “We’re very sorry this happened,” he said, and I believed him. He printed a new pick-up authorization list and introduced the concept of a “family word”—a code my son could ask for if someone claimed I’d sent them.

“What word do you want?” he asked my son.

“Octopus,” my kid said without hesitation.

“Octopus it is,” the principal said, writing it in a place only a few people would see. “If anyone tells you your dad said it’s okay and they don’t know the word, what do you do?”

“Run,” my son said. “And yell.”

“Perfect,” the principal said, and looked at me. “We’ve got him.”

We stopped by the house with an officer at dusk to collect essentials. The lock on the front door looked embarrassed as I turned it. Inside, the lights clicked on to reveal a museum exhibit titled The Life We Thought We Had. The kitchen still smelled like cumin from last night’s chili; the sink had two cereal bowls in it like someone had breakfast in a house that wasn’t theirs. The hallway camera watched me like a witness.

I packed targets, not memories. Clothes. Toothbrushes. The dinosaur nightlight from the hallway. A box of Lego’s that had more dust than joy on it. The officer waited in the entryway and didn’t comment on the framed family photo—Mara in a sundress, me with a haircut that probably cost too much, my son holding a sparkler like hope.

In the master bedroom, I paused at the closet, then didn’t open it. There are some knowledges that don’t add value. I took the good blanket and left behind the sheets. When we stepped back onto the porch, the neighbor across the street, Mrs. Chang, did the discreet wave people do when they’re trying to decide if an event belongs to them. “We’re fine,” I called softly. It was both true and not yet.

Back at the townhouse, I installed the second set of cameras I’d bought—a bell camera and a floodlight cam over the driveway. Paranoia is a word used by people who haven’t been surprised enough times. As I tightened the bracket, my phone buzzed. A text from Steve: You think you’re a hero? You’re just jealous. Leave us alone.

I stared at the words long enough to let their cheapness wear off. Then I replied once, a message my attorney would not mind reading in court. All communication goes through counsel. Do not contact me or my son again. Then I blocked him and took a screenshot of the conversation for my evidence folder, which already had its own folder, which already had a redundant cloud backup. Somewhere between the emails and the forms, grief had transmuted into logistics. Sometimes alchemy looks like admin work.

At bedtime, my son asked if we could read. He’s at the age where books are both refuge and rebellion. I pulled an old copy of Hatchet from a box because survival manuals are best delivered as stories. Halfway through the chapter where the boy learns the language of the lake, my son interrupted. “Do you think Uncle Steve is going to jail?”

“I think actions have consequences,” I said. “And I think Detective Alvarez is very good at his job.”

He considered this. “If Mom asks to see me, do I have to?”

“No,” I said. “You don’t have to do anything that doesn’t feel safe. When the judge is ready, he’ll make a plan. You can tell your truth to the people who make the rules.”

He looked at the ceiling, which is where kids go when they’re deciding if a promise is big enough to believe in. “Okay,” he said. “Read more.”

When he finally slept, I went to the gym. Not for the endorphins. For the bag. There is a red heavy bag in the corner that has absorbed whole marriages. I taped my hands slow, the ritual soothing like a rosary. The first strike sang up my arm and into my shoulder blade. I kept the rhythm my old boxing coach taught me when I was twenty-three and full of angles—two jabs, cross, hook, breathe. I imagined the bag as a door. Not a face. Never a face. Doors can take it.

On the way home, I swung by the 24-hour grocery and bought oranges, milk, bread, two kinds of cereal because the illusion of choice is ninety percent of parenting, and a pie I didn’t need but wanted because sugar is a lousy therapist and sometimes a decent friend.

The next day at ten, we sat in a pastel room with a two-way mirror while a forensic interviewer with a warm voice and butterfly earrings asked my son questions that didn’t sound like questions. “Tell me about yesterday,” she said. “What happened next?” He told her. He told her the push, the door, the lock, the jump, the cry that bit his throat on the way out. She didn’t react, which is the opposite of indifference. The detective watched from the other side of the glass like a guard at the gate of a city that has been attacked before.

After, Alvarez shook my hand. “We’ll be taking Steve in for questioning. Given the video, we’ll push for charges. I can’t promise anything, but we’ve got a case.”

“You don’t have to promise,” I said. “Just keep walking.”

He nodded. “We will.”

By Friday, the emergency custody order came through. It was a PDF that meant more than ink. Sole temporary physical custody to me; legal custody pending; supervised visitation for the mother at the Family Connection Center, two hours weekly, no overnights, transportation handled by a third party. The judge’s signature scrolled across the bottom like a stern blessing.

Mara’s attorney emailed a carefully worded response. “My client disputes the characterization…but recognizes the court’s temporary authority…looks forward to clarifying facts at the full hearing.” Legalese for she sees the cliff and would like to pretend it is a curb.

That weekend, my friend from the service, Reyes, showed up uninvited with pizza and a toolbox. He’s taller than I remember and somehow smaller at the same time—a man condensed. He hugged me like he’d been annoyed on my behalf for weeks. “You’re a stubborn idiot,” he said into my shoulder. “Proud of you.”

We changed the deadbolts on the house and installed reinforcement plates on the door jambs at the townhouse while my son drew schematics of “our base” with crayons. We walked the perimeter like we were back in-country, except the perimeter was a privacy fence and the enemy was a man with my last name.

At midnight, after Reyes left, I stood in the kitchen and thought about the night the nurse called, the too-steady voice, the way the world snapped into tabs I could organize. I rinsed a glass and set it upside down on the rack, the sound louder than it should be. The townhouse hummed, alive, unthreatening. I texted the school nurse a thank-you I should have sent earlier. She responded with a heart and He’s a brave kid. That sentence put a crack in me in a place that could hold a tree later.

Monday morning arrived like a gift wrapped in routine. Lunches packed. Backpack zipped. A permission slip signed. In the car, my son stared out the window at a world that looked the same and wasn’t. “Can I try out for basketball?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “I’ll rebound.”

He nodded, some interior calculus complete. At drop-off, the principal waved. The security guard nodded like we were part of a club no one asks to join. I watched my son push open the door and join the tide of kids. He glanced back once. I gave him a thumbs-up. He rolled his eyes but smiled, and the smile reached the unbruised part and pulled light with it.

On my way to work, my phone buzzed. A voicemail from Detective Alvarez: “We’ve arrested Steven Harper on suspicion of child endangerment and misdemeanor assault, pending the DA’s review for additional charges. He’s not walking through your door anytime soon.”

I pulled into a parking lot and let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been testing. I didn’t cheer. I didn’t weep. I just sat with the simple fact of consequence and watched it take up space in the front seat.

That evening, an email from Mara arrived through counsel: she would accept supervised visitation. She would enroll in a parenting class “voluntarily” and begin therapy. She would like to see him Saturday.

I forwarded it to Nadia at CPS and to my attorney. Then I went to the park with my son and shot baskets under lights that made the court look like a stage. He missed more than he made and high-fived me anyway after each attempt because effort counts in our house now. He asked if we could get ice cream and I said yes because restraint is for other days.

When we got home, he handed me a drawing. It was our townhouse in crooked lines, a stick-figure me on the porch, a smaller stick-figure him at the window, and a squiggly black rectangle under the eaves that I realized was the camera. He’d labeled it in block letters: EYES. In the bottom corner he’d drawn an octopus and underneath it wrote our family word, as if writing it conjured protection.

“Looks just like us,” I said, which wasn’t true but was. He taped it to the fridge like a flag.

That night, the house creaked the way houses do when the temperature drops and wood remembers being trees. I walked the rooms once, not because I needed to, but because ritual tells the brain what the heart is allowed to feel. I checked the locks, glanced at the camera feeds, set my phone on the nightstand, and listened to my son’s breath begin its slow, even rhythm.

I thought about ghosts. Not the white-sheet kind. The other kind, the ones that live in places that should have been safe. They don’t leave when you ask. They leave when you make them irrelevant. When you replace a memory with a plan. When you stand in a doorway and decide what comes through.

Somewhere after midnight, I dreamed of doors that locked from the inside and of a boy on a court under lights that felt like day. In the morning, I woke to a text from Alvarez: Arraignment set for Thursday. Want to be there? I typed Yes before the question mark had cooled.

We were moving. Not fast, not dramatically. But the earth had shifted under our feet, and for the first time in months, it tilted in our favor.

Arraignment, Orders, and the Long Work of Healing

The courthouse smelled like paper and coffee left too long on a burner. Everything there felt slightly used up—worn linoleum, tired faces, words spoken too often by people who didn’t really want to be there.

Thursday morning, I sat on a hard bench outside courtroom 3B, my son at school under the watchful eye of a guidance counselor and a nurse who knew how to call me if she heard anything in his voice that sounded off. Beside me was my attorney, Susan Clark, a woman with short silver hair and the gaze of someone who had raised three children and cross-examined a hundred liars.

“Remember,” she said, her voice low but steady, “you don’t need to testify today. This is just the arraignment. The state makes its charges, Steven enters his plea, and we see if bail is granted.”

“I want him to see me,” I said.

“He will,” she said. “But let him see calm. Calm rattles people like him more than rage ever could.”

The bailiff called us in. The courtroom was smaller than I expected. Rows of worn pews, the state seal on the wall, a flag in one corner drooping slightly in stale air. At the defense table, Steve sat in a county-issued jumpsuit, wrists cuffed, expression a mix of arrogance and unease. He still had that swagger in his posture, even chained.

His eyes found me immediately. For a second, I saw the smirk—the same one from high school, the one that used to get him out of trouble and into beds he didn’t belong in. But when I didn’t flinch, when I just stared back steady, the smirk faltered. He looked away first.

The prosecutor read the charges: Child Endangerment. Misdemeanor Assault. Contributing to the Delinquency of a Minor. She also noted that the DA was reviewing additional counts, including Unlawful Imprisonment.

Steve’s public defender nudged him, and he muttered, “Not guilty.”

The judge, a tall man with heavy glasses and a voice like gravel, glanced down at the paperwork. “Bail is set at twenty-five thousand. Given the involvement of a child and the existence of corroborating video evidence, if posted, release will include strict no-contact orders. Defendant is to remain at least 500 feet away from petitioner and minor child. Next hearing in four weeks.”

The gavel came down. That was it. Quick. Clean. And yet the sound echoed in my chest longer than it should have.

As the bailiff led Steve away, he twisted his head, as if to get one last look. His mouth moved, silent, but I knew what it said. This isn’t over.

I didn’t need it to be over. I just needed him out of my son’s life. Permanently.

The First Supervised Visit

Two days later, Mara had her first supervised visit at the Family Connection Center. A pastel-painted building designed to feel cheerful but reeking of disinfectant and anxiety.

My son clutched my hand in the lobby. “Do I have to?” he whispered.

“No,” I said honestly. “You don’t ever have to. But if you want to see her, this is the safest way.”

He thought for a long moment, then nodded. “Okay. But only if you’re close.”

“I’ll be right outside,” I promised.

We sat in the intake room until a staff member—a woman named Carla with kind eyes—knelt and explained the rules. “Your mom will be in a room with toys and games. I’ll stay the whole time. Your dad will wait here. If you feel uncomfortable, you can tell me, and we’ll stop. You’re in charge.”

My son looked at me, then at her, and whispered, “Okay.”

I watched through the one-way glass. Mara came in carrying a teddy bear, her eyes red, her hair pulled back in a way that made her look younger, almost fragile. She crouched and opened her arms. “Sweetheart,” she whispered.

He hesitated. Then slowly, carefully, he walked into the hug. He didn’t cling. He didn’t melt. He just allowed it.

They sat. She asked about school. He told her about basketball tryouts. She tried to steer the talk toward me—toward “how’s your dad been?”—but Carla redirected her gently each time. For an hour, they played Connect Four and colored pictures. My son stayed polite, but there was a distance in him, a caution that hadn’t been there before.

When time was up, Mara kissed his forehead. He let her. Then he came out and immediately grabbed my hand again. “Can we go now?” he asked.

“Yeah, buddy,” I said. “We can go.”

In the car, he was quiet. Then he finally said, “She cried a lot. But she didn’t say sorry for Steve.”

I gripped the wheel tighter. “That’s not on you. That’s on her.”

He nodded, pressed his forehead to the window, and whispered, “Good.”

Building a New Normal

The weeks that followed became a strange mix of ordinary and extraordinary.

Ordinary: school runs, soccer practices, frozen pizza dinners, late-night math homework.

Extraordinary: meetings with lawyers, CPS check-ins, police updates, counseling sessions where my son learned words like trauma and boundaries.

We established routines because routines are scaffolding. Every Friday night became pizza-and-movie night. Every Sunday morning, pancakes with chocolate chips. I gave him chores—not as punishment, but as proof that he mattered, that the house needed him to run.

Therapy helped too. Dr. Patel, a child psychologist with a soft voice and bright scarves, taught him to name his feelings without fear. He drew pictures of doors—closed, locked, then slowly opening. “Safe doors,” he explained.

Sometimes he still woke at night, sweaty, eyes wide, whispering, “He’s here.” I would sit with him until the panic ebbed. Sometimes I fell asleep in the chair by his bed, waking with a stiff neck but no regrets.

I didn’t shield him from the truth. Kids know when you’re lying. Instead, I gave him just enough. “Steve’s in jail right now,” I told him once. “The judge decides what happens next. But he won’t touch you again.”

He believed me because I said it like a soldier giving coordinates. Certain. Final.

A Visit from the Past

One evening, while I was reheating leftovers, there was a knock at the door. Not a neighbor’s tap, not a delivery’s ding-dong. A steady, deliberate knock.

Through the peephole: my sister, Laura.

When I opened the door, she hugged me hard, her perfume sharp with nostalgia. “I came as soon as I heard,” she said.

“You’re three weeks late,” I said, but without anger.

“News travels slow when no one wants to tell you,” she said. “But I’m here now. Where’s my nephew?”

He barreled into her arms, and for the first time in weeks, I saw him laugh like a kid again. She sat cross-legged on the floor and played cards with him while I watched, a lump in my throat.

Later, when he was in bed, she turned to me. “I always knew Steve was trouble. But this…?” She shook her head. “I should’ve warned you harder.”

“You did,” I said. “I just didn’t want to listen.”

She put a hand on my arm. “You’re listening now. That’s what matters.”

Preparing for the Next Battle

The DA’s office called the following week. “We’re upgrading charges to felony child abuse and unlawful imprisonment,” the prosecutor said. “Video evidence is solid. We’ll push for trial unless he takes a plea.”

Susan, my attorney, smiled when I told her. “That’s leverage,” she said. “Don’t expect miracles, but he’s not walking away with a slap on the wrist.”

Meanwhile, Mara’s lawyer pushed for expanded visitation. Susan countered with the footage, the CPS report, the fact that Mara had failed to protect her own son. The judge wasn’t swayed by tears this time. “Visitation remains supervised until further order,” he ruled.

Each small victory felt like sandbags against a flood. Temporary, maybe. But enough to hold.

Clarity in the Quiet

One night, after my son finally fell asleep, I sat in the living room alone. The cameras showed empty hallways, locked doors, stillness. The evidence drive sat in my desk, double-copied, triply secure.

I thought about what my drill sergeant used to say: The fight isn’t over when you win. It’s over when the other side can’t get back up.

Steve had touched my son once. That was enough to end him. Mara had let it happen. That was enough to end us.

And me? I wasn’t broken. I was deliberate.

The truth was my weapon. And it was doing the work for me.

The Trial, the Verdict, and the Weight of Moving On

The trial was set for late spring. By then, the bruises on my son’s face had faded to yellow, then gone entirely. But scars aren’t only skin-deep. Some of them live behind the eyes, flickering in the silence before sleep. He still checked that his bedroom door was locked three times before bed. Still asked me to read Hatchet out loud, like survival stories were lullabies.

We’d been in therapy for months. Dr. Patel gave him a “feelings chart” to point at instead of speaking when words felt too big. Sometimes he jabbed at angry, sometimes scared. Once, surprisingly, he pointed at hopeful. That one I taped to the fridge.

I needed it too.

The DA’s Office

In the weeks leading up to trial, I sat in the DA’s office more often than I sat in my own. The prosecutor, a sharp-eyed woman named Nguyen, spread files across her desk like battle plans.

“Your footage is airtight,” she said, tapping a still shot of Steve with his hand on the door, my son’s small figure blurred in the background. “We’ll use this as Exhibit A. Then we line up your son’s testimony via recorded forensic interview. The jury will hear it, not see him. He won’t have to sit in the same room as his uncle.”

“Good,” I said. “He’s eleven. He doesn’t need to look at him again.”

Nguyen leaned back. “Your brother’s attorney will try to spin this as a family dispute, maybe claim you manipulated the evidence. They’ll throw everything they can at the wall. But I’ve tried enough of these cases to know when the wall’s made of stone. This one is.”

I didn’t say thank you. Gratitude didn’t belong here. Evidence did.

Courtroom Theater

The courtroom was fuller this time. Reporters in the back row, notebooks ready. A few curious locals who smelled drama. Family court and criminal court always draw vultures.

Steve sat at the defense table, suit borrowed or rented, hair slicked back. He looked smaller than he had at arraignment, though he tried to wear his smirk like armor. Mara wasn’t beside him; she sat a few rows back, alone, twisting a tissue into threads.

When the video played, the room went silent. No coughs, no shuffling papers. Just the grainy image of betrayal projected onto a screen too large. My son’s voice carried through the speakers, asking, “Can I go back to school?” followed by the slam of the door.

Even the jurors flinched.

Steve’s attorney objected, of course. Claimed the footage lacked “context.” The judge overruled. “The footage speaks for itself,” he said, his voice colder than the marble underfoot.

I sat still, hands folded, face blank. Calm rattles men like Steve. Rage feeds them. Calm starves them.

Mara on the Stand

The day Mara testified, I felt the old ache of recognition in my chest. She looked tired, makeup cracking under fluorescent lights. Her lawyer guided her gently, trying to coax out a picture of a woman overwhelmed, manipulated, caught in circumstances beyond her control.

But under cross-examination, Nguyen cut through the facade.

“You were in the home that day, correct?”

“Yes.”

“You saw your son with a black eye, correct?”

Tears welled. “Yes.”

“And you did not call the police. You did not seek medical care. You allowed the defendant continued access to your child.”

“I thought—”

“No,” Nguyen said, firm but not cruel. “You chose. You chose not to act. And your son paid the price.”

Mara broke then, sobbing into her hands. The judge allowed a recess. I sat stone-still, my pulse steady. This wasn’t vengeance. This was exposure. And exposure is lethal to lies.

The Verdict

After six days of testimony, the jury went out. They were back in less than three hours.

Guilty on all counts.

Steve’s face went pale, his smirk finally collapsing into something raw and ugly. The judge sentenced him to eight years in state prison, parole eligibility in four. Not long enough for me. Long enough for my son to grow into a teenager who would never again fear him in the hallway of his own house.

When the gavel fell, I didn’t cheer. I didn’t cry. I just exhaled.

Outside, reporters shouted questions. “Do you have a statement? How do you feel about your brother’s conviction?”

I kept walking, my hand on my son’s shoulder. “No comment,” I said. The only audience I cared about was eleven years old and holding a basketball under his arm like a shield.

Aftermath

Mara’s supervised visits continued, but they grew fewer. My son stopped asking for them. After one visit, he came home, dropped his backpack, and said, “She still doesn’t get it.”

I didn’t argue. Some truths children shouldn’t have to carry, but this one he did, and he was right.

By summer, Mara moved out of state. She sent birthday cards, stiff with Hallmark apologies. He read them once, then left them unopened on the counter. Eventually, he stopped opening them at all.

Moving On

Life didn’t snap back to normal. It built something new. Different. Stronger.

My son made the basketball team. I coached from the sidelines, cheering louder than I meant to. He made friends, learned to laugh again, even started teasing me about my terrible cooking.

At night, sometimes, he still asked me to sit in his room until he fell asleep. I always did. And every time, when his breathing evened out, I whispered the same words to the dark: “We’re safe.”

Not because I needed him to believe it, but because I finally did.

Closing the Circle

Months later, when I packed away the cameras into a storage box, my hands shook. Not from fear, but from relief. Their job was done. The truth had already spoken.

I kept one photo on my desk—a drawing my son made of our townhouse, the camera drawn as a black square above the door, the word “EYES” written underneath in block letters. Protection in crayon. Proof that even children understand the power of being seen.

Steve touched my son once. That was enough to end him.

And me? I learned something in the rubble of betrayal.

Blood doesn’t define family. Protection does. Love does. Truth does.

And the truth—always, eventually—wins.

The End

News

My Parents Trapped Me With A $350,000 Mortgage Papers. But They Didn’t Know, I Had Already Moved… CH2

The First Goodbye Grandma Rose was the only person who looked me in the eye when I talked. Not over…

Stepmom Pushed Me Down The Stairs—Dad Said ‘It Was An Accident.’ The Security Camera Proved Other… CH2

The Night the Mask Slipped The heart monitor beeped like a metronome for anxiety—steady, insistent, incapable of taking a hint….

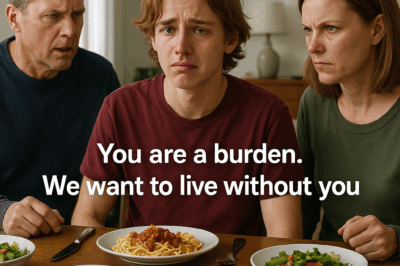

At the Family Dinner, My Parents Said, “You Are a Burden, We Want to Live Without You.” So I… CH2

The Night I Stopped Clapping Lincoln, Nebraska has a few traditions that hang on no matter how many new coffee…

My parents told my daughter that she is NOT “our family”… CH2

The Night the Ground Moved At 6:49 p.m., my biggest dilemma was whether we had enough spinach to pretend dinner…

My Sister Laughed When Her Spoiled Kids Destroyed My $2K TV, But She Regretted When I Said… CH2

The Day the Vase Shattered If you’ve ever had your name saved in the family group chat as “Autumn (the…

She Publicly Said My Husband Wasn’t My Kids’ Real Dad – My Daughter’s Response Shocked Everyone CH2

The Lake, the Linen, and the Eleven Words I never thought a six-year-old could detonate a dynasty with eleven words…

End of content

No more pages to load