My Husband’s Family Rejected Me For Being Poor, But A Year Later Our Paths Crossed Again…

Part One

The words weren’t loud, but they landed with the heavy certainty of a judge’s gavel.

“She’ll never be good enough for a Lynch.”

I had been holding a coffee mug when Tiffany said it—bone china with a tiny chip in the handle I always lined up toward the cupboard so no one could see. It trembled in my hand, a ridiculous detail to focus on when your mother-in-law has just declared you unworthy in your own kitchen. The afternoon light cut through our apartment in sharp rectangles, making everything too bright. I looked at my husband, at Easton—the man whose laugh had once felt like the safest place I knew—and I watched him disappear a little as he stood between his mother and his suitcase.

“You can’t just leave,” I said. My voice came out small and uneven. “After everything we’ve been through?”

His shirts—so many white ones that never came out of the dryer without needing the iron—were folded with the automatism of muscle memory. He wouldn’t look at me. “My family… they’re right, Delila. We come from different worlds.” He winced. “I tried to make them understand, but—”

“But what?” I took a step closer. “My background isn’t prestigious enough? My dad wasn’t a CEO? I worked my way through school and waited tables and saved? That makes me what—contagious?”

Tiffany stood in the doorway like an oil painting, her designer suit the color of money. Her nails clicked against the leather of her clutch, and she didn’t so much as glance at the mug in my hand or the ring on my finger or the life in the photos on the fridge we’d stuck there with magnets from places we’d thought we’d go again. “Easton, darling,” she said, ignoring me so hard it was a skill, “the car is waiting. Your father’s expecting us for dinner.”

Easton’s shoulders dropped. I recognized the particular slouch of a boy sent to fetch wood in the rain. The man I loved could stand in front of a boardroom and talk numbers like poetry, could parallel park a vintage Mercedes like it was a daily prayer, could cook eggs with a flick of the wrist that always made me laugh, and he couldn’t move an inch in his mother’s shadow.

“You should have seen this coming, dear,” Tiffany added, turning the thin blade of her pity in my direction. “Someone like you—well, you must have known it was temporary.”

Someone like me. The words might as well have been a stain she wanted to scrub out. Heat flooded my face, anger and humiliation and the bristling need to throw something. I took a breath because, in my experience, throwing only made it louder. “You mean someone who got up at five to open a diner before lectures. Someone who knows what rent day feels like. Someone who has value that doesn’t come with a last name.”

“Delila,” Easton said weakly.

“No,” I said, turning to him and not to the woman who had never once asked me how my day was and would have been offended if I’d told her. “No. You chose them.”

He flinched.

I slid my ring off my finger. It had felt like a promise when he’d put it there in a church full of hydrangeas. Now it felt like a shackle. I set it on the counter. The sound it made—small, sad—was the last uninvited apology I planned to make on the Lynch family’s behalf.

“I understand perfectly,” I said to Tiffany. The humorless smile that came out of me belonged to a woman I hadn’t met yet. “Congratulations. You’ve won. Remember this moment. Not because I’m threatening you.” I placed the mug carefully in the sink. “Because I’m promising myself what comes next.”

I walked past them. I didn’t slam the door. I wanted the quiet to carry.

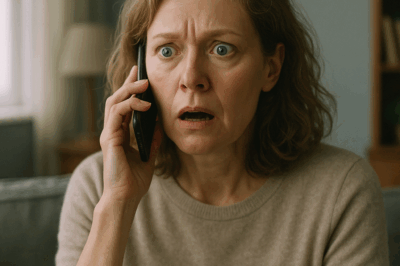

In the car, my hands shaking on the wheel, I called Bridget because she has always known how to pack a life into a trunk in twenty minutes and make you laugh halfway down the stairs. “He’s gone,” I said.

“I’m coming,” she replied. “Pack your essentials. You’re staying with me.”

“I have rent—”

“You also have a spine. Bring that.”

That night, curled on Bridget’s couch with a glass of wine and the smallest, coldest piece of strawberry pie I’ve ever eaten, I watched the city from a window that wasn’t mine and told myself a thing that felt like a lie and a vow simultaneously: I would rebuild. Piece by piece. I would not spend the next decade of my life telling the story of how the Lynches broke me.

“To new beginnings,” Bridget said, clinking her glass against mine.

“To revenge served cold,” I said and surprised myself with the steel in it. “Not with poison,” I added, because I am not the kind of woman who knows how to be cruel elegantly. “With success.”

I fell asleep with my face in a throw pillow and woke up with the imprint of its pattern on my cheek and the shape of a plan growing where hurt had cleared ground.

“You can’t mope around my apartment forever,” Bridget announced two weeks later, yanking the curtains open so aggressively the rod stared rattling like castanets.

“I’m not moping,” I lied into a blanket.

“You’re strategizing with Netflix and ice cream,” she translated. She sat on the edge of the couch. “We’re going downtown.”

“To do what,” I asked. “Buy disappointment in a different zip code?”

“To sign a lease,” she replied, scrolling on her laptop, face lit with the fervor of a woman on a mission. She turned the screen to me. “Commercial space. Affordable. Good bones. Close to the farmers market.”

The number on the listing made my stomach perform a small, concise flip. “I can’t—”

“You can,” she said firmly. “Remember the organic skincare you used to make? Everyone at the wedding raved about that face cream. Even the Wicked Witch of Wealth complimented your skin before she realized it was you and not a product she could buy at Neiman’s.”

“That was a hobby,” I protested. “A coping mechanism that made the apartment smell like lavender for three days.”

“It was a proof of concept,” she countered. “Del, there’s a massive market for clean, sustainable beauty. And you already have formulas. You’re good. Not to mention the hands of a saint with a whisk. The only thing you don’t have is the curse of a family name, and somehow we’ll survive that.”

We walked to the coffee shop because it is where we plot. The bell chimed when we opened the door because the universe has a sense of drama. We ordered the thing we always ordered—her: black, me: latte—and took the corner table.

“Excuse me,” a man in a sensible blazer said as we passed. He smiled with his eyes first. “I couldn’t help hearing—”

“Which means you were listening,” I said, but his grin made it less of an accusation.

“I’m Leonard,” he said, standing and offering a hand. “I help people start and scale things. And I heard the words ‘organic skincare’ and ‘farmers market’ in the same sentence.”

“That is exactly what you heard,” Bridget said before I could decide if this was fate or a line. “And this is Delila, and she happens to have samples.”

“Bridget,” I hissed, but she was already rooting in my tote.

I’d never admit it, but I do carry small jars like a talisman. Leonard unscrewed a lid, sniffed, and rubbed the cream into the back of his hand with the kind of appreciation people usually reserve for slow-cooked meat. He asked questions about sourcing and margins and ecological footprint the way other men ask about sports. When he slid his card across the table, I buckled internally.

“Fifteen years ago,” he said, “a woman who wore overalls and had paint on her fingers sat at a table like this and told me about the furniture she wanted to make. She has three stores now. Somebody took a chance on me when I was young and ridiculous. It would be nice to pay that forward.” He smiled. “Call me.”

He left. Bridget grabbed my hand and shook it like I’d just won a raffle. “See? You leave a Lynch,” she said, “and the universe sends a Leonard.”

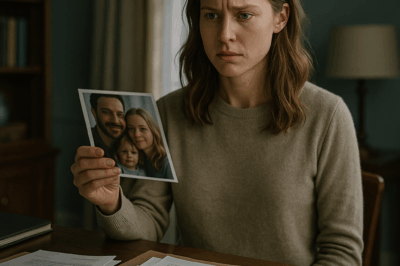

That night, I pulled out my recipe journal—a stained, painstaking book of hand-written formulas, customer feedback scrawled in margins, and percentages calculated next to notes about rose oil and shea butter costs. Tiffany had once called it “your little kitchen project” with a smile that had felt like a slap. I ran my hand over the cover. It felt like the back of a life.

In the morning, I called Leonard.

Three months later, I stood in my own small production space, the air warm with beeswax and possibility. Stainless steel tables reflected jars lined up like soldiers waiting for inspection. Labels I had designed at two in the morning when the dog in the unit next door would not stop barking lay in tidy stacks. A sign above the door read Freeman Naturals because sometimes you reclaim a name by putting it on the wall.

“To Freeman Naturals,” Bridget said, hoisting a glass of champagne leftover from a life I no longer wanted. “In your face, Tiffany.”

“You did this,” Leonard corrected gently. “Bridget and I cheered and called vendors and sent stern emails, but you did this.”

He was reluctant when he said it, but he brought up the trade show. “If you want to be in retail, it’s the place,” he said. “It’s also a circus. The expensive kind. But I have relationships. We can do a modest booth. You have what they don’t: a story not made up by a creative director.”

“‘I got dumped by a rich man and decided to make moisturizers’ is not what they mean by brand story,” I said.

“‘I care about what you put on your face because I have cleaned toilets’ is,” he said. “Trust me.”

The first morning of the show, the Convention Center made my modest booth feel like a child’s lemonade stand at a yacht party. Across the aisle, a beauty conglomerate built a two-story jungle with living walls and a barista who could draw their logo in the foam of your latte. Our back wall was recycled barn wood. Our jars were glass with simple labels that explained ingredients like we weren’t trying to hide anything. Leonard adjusted our banner. “It’s not about size,” he murmured. “It’s about resonance.”

Early traffic passed us by like we were a quaint tableaux. Then a woman paused. She was in her sixties, a face of elegant lines and the kind of earrings you inherit. “May I?” she asked, dipping a fingertip into the tester.

“Of course,” I said. “That one’s rose and geranium. We source the oil from a family farm that uses gray water to irrigate.”

Her eyes closed in appreciation. “My skin hasn’t liked anything in months,” she said. “This… likes this.” She smiled. “I’m Margaret from Bloom. We have six boutiques. Would you be open to wholesale?”

Before lunch, three more stores had asked. By afternoon, a blogger with six hundred thousand followers posted a photo of my jar with the caption finally something that feels like it was made by a human and our booth filled with women who wanted to touch and smell and ask me where I was from.

“Here,” I said, smiling so hard my cheeks ached. “I am from here.”

Which is when Noel—daughter of a family who’d sent Tiffany Christmas cards so heavy the postage was obscene—appeared. She glanced around our booth with the cataloging gaze of a catalog. “How quaint,” she said, dragging a red nail across one of our labels. “I represent Lux Beauty now. We’re launching an organic line next month. Just wanted to see what the… competition is up to.”

“We’re sold out of travel sizes,” I said, and the laugh Leonard choked out behind me saved me from something less elegant. Noel’s gaze slid to our order book, and the flicker of annoyance when she saw signatures lifted my spirits more than I care to admit.

By day three, my voice wore hope like a shawl. A magazine asked to feature me as a “rising star,” which made me want to sit down and drink water. The timing—out just before Lux Beauty’s launch—made Leonard’s smile do interesting things.

The night we packed up the booth, my feet begged for mercy. Leonard handed me an envelope. “Charity gala wants a speaker,” he said. “Theme: innovation and sustainability. They want you to talk about building a clean beauty brand.”

“That’s wonderful,” Bridget squealed. “Who’s hosting?”

I read the stationery. My throat closed. Lynch Foundation Annual Gala.

“You don’t have to,” Leonard said, watching my face.

“I do,” I said. “I think I have to find out what my spine does on a stage.”

Bridget raised her glass. “To facing the dragon with moisturizer.”

By the week of the gala, Freeman Naturals was more than a sign. The magazine feature sent orders through the roof. I moved production into a larger space without compromising a single thing I cared about. We brought on two women from the neighborhood who needed work that paid a living wage and had child care during school holidays. I made a list of sustainability goals and taped them to the wall where everyone could see them and argue with me.

And then Ricardo—Easton’s father—stopped me on the sidewalk outside my dress fitting. “Delila,” he said, and I didn’t know what to do with the way my name sounded coming out of his mouth.

“Mr. Lynch,” I said, because I am my mother’s daughter when it comes to manners.

“We… saw your name on the program,” he said. “Tiffany and I…” He trailed off. He looked older. Time had tugged at him.

“Congratulations on reading,” I said. It was petty. It felt good.

He winced. “We were wrong about you.”

“No,” I said, feeling the steadying press of the seamstress’s pins against my ribs. “You were exactly who you are.”

I went back inside and chose a dress that felt like something a woman who washed dishes in three apartments and had her heart broken by a man who didn’t know what to do with something real would wear while telling a room full of people that they don’t get to define her.

The day of the gala, the hotel’s chandeliers looked like they might faint under all the light. The Lynch Foundation’s crest hung above the stage like a warning and an invitation. We were seated near the front because Leonard knows how to secure seating assignments with smiles.

“You’re before Noel,” he said. “They moved you up.”

“Of course she did,” Bridget hissed. “She can’t sit with the discomfort of following a woman who actually did something.”

I was reviewing my notes in the speaker prep room when he appeared in the doorway.

“Delila,” Easton said, and my body remembered the tingling of annoyance it used to call love.

“Don’t,” I said without looking up.

“You look—”

“Don’t,” I repeated.

“I made a mistake,” he said, because time gives every man the first sentence of an apology and leaves the rest for people who can write.

“You made a choice,” I corrected. “And now you get to live with it.”

“I miss you.”

“No,” I said, finally meeting his eyes. “You miss how easy it was to be adored by someone who thought you were better than you were.”

“My family—”

“I don’t need your family’s postmortem,” I said. “I need to find my spotlights cue.”

He stepped aside, and I walked into the hall, nearly colliding with Tiffany’s perfume.

“Delila,” she said, and the way she tilted her head made me want to adjust the chandelier above her so it fell on the floor and not on anyone’s head. “We must be civil.”

“It’s a gala,” I said. “I’m wearing heels. I can be anything.”

Her smile tightened.

When they announced me, the room tilted for a second. It righted itself when I began.

“A year ago,” I said, and thirty linen covered heads turned in unison. “A woman told me I wasn’t good enough. She meant it as a sentence. I took it as a beginning.”

I told them about beeswax and water reclamation and the difference between a product designed by a boardroom and a jar filled by a woman with knowledge in her fingers. I told them that sustainability isn’t a buzzword—it’s an ethic. I told them that clean beauty that does not include fair wages is a lie with a floral scent.

“The thing about being dismissed,” I said, looking directly at the table where the Lynches and their donors sat rigid and glittering, “is that it’s directional. It shows you what door not to knock on. So you build your own.”

The applause rose like a tide. I looked over at Leonard. He nodded. I looked at Bridget. Her face was wet. I looked at Easton. He looked like a man being introduced to himself.

Then Noel took the stage.

Her voice was syrup. The wording in her presentation was dangerously close to mine. Her ingredients list was dangerously closer. Leonard leaned in. “Wait,” he whispered.

I didn’t have to. The screen behind her flickered and then changed. A legal notice took up the wall where her slide should have been.

“Miss Simmons,” a man in a suit said into a live mic, the words rolling out like a red carpet I hadn’t asked for. “On behalf of Freeman Naturals, we need to inform you that the formulation you’re presenting appears to infringe on patent 7—”

The room buzzed like an angry hive. The coordinator hustled. The rich blink. Noel hissed, “You did this to me,” as security escorted her off the stage.

“No,” I said softly. “You did it to yourself when you thought imitation would carry you farther than integrity.”

Tiffany looked like she’d bitten a lemon. Easton put his face in his hands. And then, because the universe likes a neat tie, my phone vibrated with a notification that our web traffic had quadrupled.

“We should go,” Leonard said after Noel left the room with two lawyers and zero dignity.

“Not yet,” I murmured, looking over the balcony at the table where the Lynches sat trying not to be seen. “I think the dessert bar has chocolate tarts.”

The next morning, the magazine’s website had my face on it and the words David meets Goliath with cleanser. The Lux Beauty stock dipped. Noel posted an apology video with a shaky voice and good lighting. It was genuine enough that I watched to the end and nodded to myself.

At ten o’clock, her lawyers came to my office with settlement offers. “No,” I said. “This isn’t about money. This is about truth. You’ll post a full admission. You’ll step down.”

The younger attorney looked like he might cry into his tie. Noel, to her credit, didn’t argue. “You’ve built something real,” she said. “All I did was buy dresses.”

As they left, my receptionist whispered, “There’s someone else—” and Tiffany walked into my lobby alone for the first time in her life.

“I would like to make a statement,” she said stiffly. “Publicly.”

“There are journalists in the conference room,” Leonard said.

We walked in together. She faced the cameras and did the hardest thing a woman with her money can do: she admitted she’d been wrong.

“We equated pedigree with worth,” she said. “We equated polish with virtue. We were incorrect.”

“Why now?” a reporter asked.

“Because my granddaughter asked me why we treat some people differently than others,” she said, and for a second I saw the girl she might have been if someone had loved her better. “And I didn’t want to be the kind of grandmother who couldn’t answer.”

After, she turned to me. “We’d like to fund a scholarship,” she said. “For entrepreneurs who don’t have… us.” She gestured at herself. “Would you help us pick?”

“Yes,” I said, because redemption matters when it arrives as work, not performance.

On the balcony later, the city looked scrubbed. Bridget handed me a glass of champagne because she is ceremonial about my milestones. “Exes texting?” she asked.

“Easton,” I admitted. “Congratulations. You deserve this.”

“And you wrote—” she began.

“I wrote, ‘I am happy. I hope you find your happiness, too.’” I sipped. “It felt… accurate.”

“Look at you,” she said. “Complete.”

“Invincible,” I corrected with a grin that felt like mine again. “On my good days.”

Below us, the sign we’d hung last week on the building across the street glowed in the early evening: FREEMAN NATURALS. We’d chosen a font that looked modern and classic at once; authenticity sells when typography does its job.

“Ready for what’s next?” Leonard asked, stepping onto the balcony with a sheaf of contracts. “Europe wants you.”

“Europe can have me Tuesday,” I said. “Today I’m going to sit in my office and breathe.”

He smiled. “The most sustainable practice of all.”

A year later, I would tell this living room full of women—the ones who come for mentorship because they have ideas and are told they should not—that the moment in the kitchen when Tiffany said never had been the making of me. I’d tell them that there is no revenge as efficient as a ledger with your name at the top. I’d tell them that you can be born into money or into grit, but you will always have to choose who you are when someone pushes you.

“To never letting anyone make you feel small,” Bridget said that night, raising her glass one more time.

“To building rooms where size is irrelevant,” I said, clinking back, “and putting the table in the middle so everyone knows where to sit.”

Part Two

The sun set behind our new headquarters in long orange strokes, and the ribbon fluttered down like a comet tail. The crowd scattered into tours and conversations. The scent of beeswax, lavender, paper, coffee, and new paint mingled into something I wanted to bottle.

“Before we start, one more thing,” I said into the mic, the wooden platform under my heels as steady as my new voice. “Today we’re launching a global initiative to make clean, sustainable beauty accessible. Scholarships for formulators. Grants for founders from communities wealth tends to overlook. Education in schools about reading ingredients. Products that are affordable and good.”

Cameras flashed. Someone in the back whispered, “Of course she would.”

From the edge of the crowd, a hand went up. Not a journalist’s. Tiffany’s.

“May I say something?” She stood straighter than she had in the conference room, the pearls at her throat suddenly less armor and more artifact. She moved to the front with the caution of someone who has misstepped on this stage before.

“Mrs. Lynch,” I said evenly. “What a surprise.”

“I came to make amends,” she said, voice shakier than I had ever heard it. “Publicly.”

Leonard angled a microphone toward her. The press turned. She breathed. “We were wrong about you. About… the many yous we dismissed because we thought last names were a map. We have spent a year considering what kind of family we want to be. We are sponsoring Delila’s initiative. And we are endowing a fund in my mother’s name for business owners who remind me of the girls from my boarding school I didn’t try hard enough to be like.” She lifted her chin and looked at me. “We would be honored if you chaired it.”

There were audible gasps. There were also some smirks; the city is a cynic when it needs to be.

“Thank you,” I said simply, because life is long and stubborn and sometimes forgiveness is policy, not affection. “Yes.”

Ricardo stepped forward and shook my hand with both of his. “My granddaughter,” he said softly, “likes your lip balm.”

“That is the only review that matters,” I replied.

Bridget sidled up with a tablet. “Look,” she whispered, showing me a video Noel had posted an hour earlier: her apology, thoughtful and specific, naming what she’d done and what she had learned and who she wanted to be. “We can work together, in time,” she said at the end, and I filed the sentence under Business Decisions To Make Later.

Orders spiked. Europe called. Asia emailed. The local high school asked if I’d come speak to the girls in entrepreneurship club, and I said yes because for three years in a row the only person who visited them was a man named Craig who sells insurance.

The Lynches left. Easton texted I’m proud of you. I liked the message and did not reply, which is as kind as I could be. Tiffany lingered, watching the women on my team test batch nineteen of the new eye cream. She touched a jar and then pulled her hand back, as if she thought she’d break it. “You built all this,” she said.

“Yes,” I said, and turned away to answer a teenager’s question about retail margins.

We had a schedule now: mornings in the lab, afternoons in meetings, evenings for the part where you hold someone else’s dream up to the light and show her where it’s already shining.

At the end of the day, the building emptied into the kind of quiet that makes you love your work again. I stood at the window in my office, looking out at the city and at our sign glowing like a little home star. Leonard knocked and came in, settling on the corner of my desk.

“You were very gracious,” he said. “With Tiffany. With Noel.”

“I am unwilling to carry bitterness when there are boxes of inventory to carry,” I said.

“A practical mysticism,” he mused.

“You sound like my therapist,” I said.

“You can fire me and keep her,” he said. “I won’t mind.”

“You’re stuck,” I said. “Contracts were signed.”

We toasted with tap water in mugs that said “sweat equity.” The office light flickered and then warmed. The dog from next door scratched at the door. I let him in. He made a revolution and collapsed with the sort of sigh we all wish we were capable of.

“Remember when you said success is the best revenge?” I asked.

“I said that because I am pithy,” he replied. “You made it true.”

“Can I add something?”

“I wouldn’t stop you.”

“Success is the best revenge,” I said, “and also the best beginning.”

The year turned again. We expanded into three more cities. We kept manufacturing in-house despite a dozen very persuasive men in suits offering to “streamline.” We started a school partnership program—chemistry class, but with rosewater. Esme built an inventory system so elegant we nominated it for an award. The women from the apprenticeships opened their own micro-brands and took booths at the very trade show where I had once stood with quaking hands. We brought tissues and cheered and wrote Instagram captions for them when words got stuck.

At home, the walls held the colors I had chosen with a mood board and stubbornness. The couch had new pillows because a life coach on a podcast told me you need at least one ridiculous textile to remind you you’re allowed to be comfortable. The cabinet that had held chipped bone china now held jars of cream because sometimes your past catches up and then sits down and asks for forgiveness; sometimes you put it to work.

A year to the day since I put my ring on the counter, a box arrived addressed in Tiffany’s slanted hand. Inside, my wedding ring lay on cotton like a story that had become an object. There was a note: I found this in a drawer with the batteries and things we forget. I did not trust myself with it. It belongs with you, in whatever way you decide. I held the ring up. It flashed like a thing that once meant forever and now meant choice. I closed the box and put it at the back of a drawer I use for bandages and safety pins.

We hosted a fundraiser for our scholarship fund. The sign outside said OPEN TO EVERYONE. The neighborhood came. People gave ten dollars and one woman gave a check with too many zeros and wrote no fuss in the memo line. The teenagers sold cookies. The dog wore a bow tie. I gave a speech about perseverance that included the words dishwasher and perimenopause and got a standing ovation that made me blush so hard I had to sit.

After, as Bridget and I wiped counters that the cleaning service would have handled in the morning, she stopped and leaned on the island we had re-installed in my office kitchen just because. I waited.

“Want to hear something wild?” she said.

“What,” I asked.

“I’m proud of the way you didn’t burn it down,” she said. “It would have been easy. Cheaper, in some ways. Faster.”

“I would have burned my fingers,” I said.

“That, too,” she said, and flicked water at me in a gesture that belonged to who we were before all of this and wanted to have its say.

We turned off lights. We locked doors. We stood at the street before we split for our cars and looked up at the sign. It lit our faces. It lit the sidewalk. It lit nothing and everything.

The last text I got from Easton came on a Sunday evening when I was watching a show about women who solve crimes with pie. I’m happy you’re happy. I wrote thank you and turned the phone face down.

The first text I got from a girl named Lena, who had been accepted into our first cohort of scholarship recipients, came an hour later. It was a picture of her kitchen table covered in botanicals and beakers and labels with a shaky hand. Look, Ms. Freeman! she wrote. I made something real. I sent her a heart reaction and then wrote: You made something beautiful. It won’t be your last.

Sometimes revenge is a ballroom and a microphone and a perfectly timed legal notice projected on a screen. Sometimes it is an apron and a sink and a fifteen-year-old girl in an apartment kitchen practicing brightness.

In the end, the thing that stuck was not the look on Tiffany’s face or the way Easton’s hand shook when he apologized in a hallway. It was the sight of a woman—me—standing on a small stage saying, “Here is who I am without the story you told about me,” and a room full of women catching that sentence and carrying it away like something they could plant.

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

End of content

No more pages to load